Inside the Reopening of The Menil — a Texas Museum Masterpiece Comes Back to Life: The Early Reviews Are In, and They’re Smashing — It’s Art and Awe

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 09.28.18The Menil Collection's front lawn. (Photo by Daniel Ortiz)

At twilight last Sunday, a band of art-world confidants gathered at a chic Montrose restaurant. An artist, an architect, a gallerist.

The group had come together for a glass of wine after an afternoon of art viewing — but this was no ordinary jaunt to take in paintings and sculpture.

The day had marked the reopening weekend of one of the jewels of the world’s museums.

The trio — artist Terrell James; her architect husband, Cameron Armstrong; and gallerist Devin Borden — was basking in the late-afternoon light at a plum spot on the patio of Bistro Menil.

I encountered them on the way to investigate the just-unveiled Menil Collection, which reopened the day before after being shuttered since late February for a refresh — floors, lighting, facility upgrades — to its serene Renzo Piano building.

The band of art insiders waved me over, but I deferred, eagerly intent on checking out the new iteration of the museum, where 780-some works had been culled from the approximately 17,000 assiduously assembled by the late Dominique and John de Menil beginning in the years before World War II, when the couple’s curiosity about collecting artists of their time and works from across the ages first germinated.

Director Rebecca Rabinow also used the closure for a reinstallation of the museum’s permanent collection, challenging her curatorial team to take a fresh look, often pulling treasures never or rarely seen before and bringing them out to see the light of day.

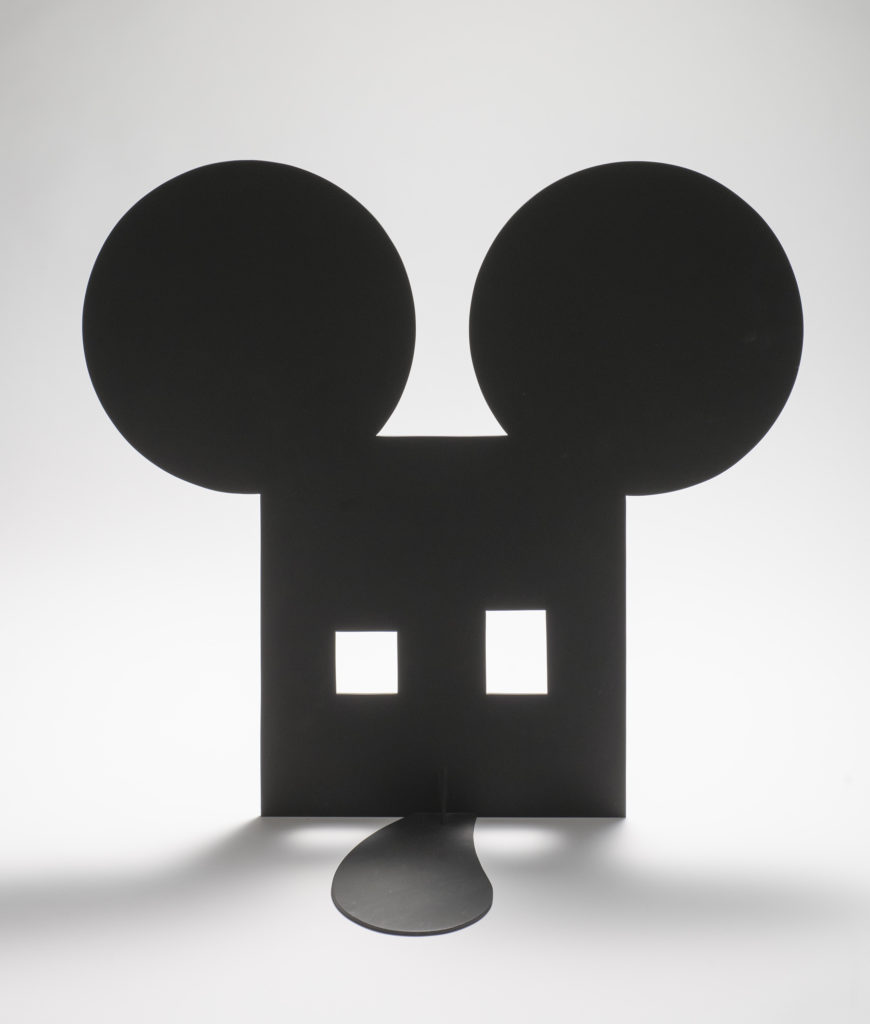

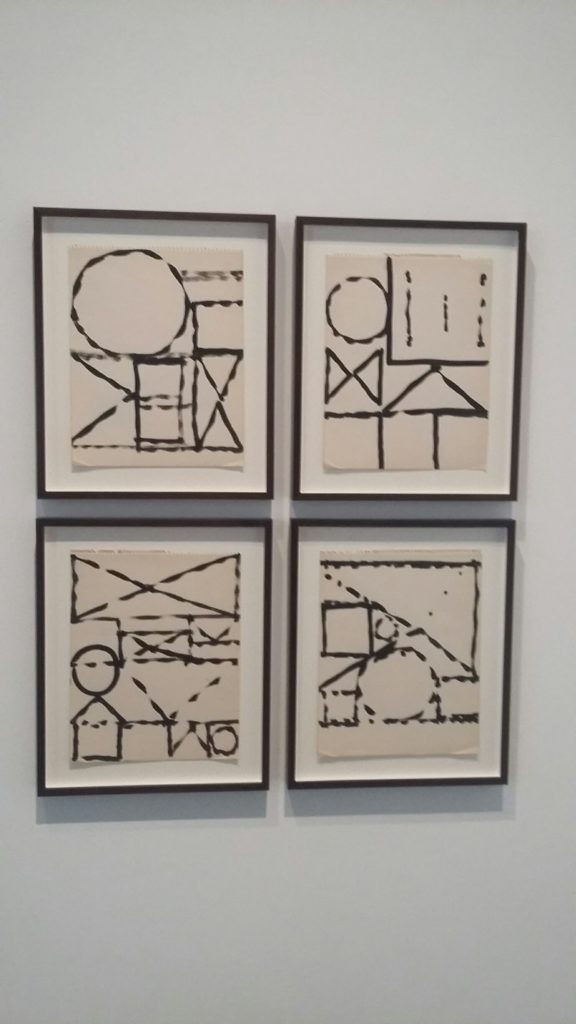

The four who were tapped for the task, steered by the guiding hand of Rabinow, were: senior curator Michelle White, who presides over modern and contemporary; curator of collections Paul Davis, whose domain includes ancient, African, Oceanic, Byzantine, and Northwest Coast; associate research curator Clare Elliott, whose expertise is Surrealism; and Kelly Montana, assistant curator at the new Menil Drawing Institute, who organized the droll Collection Close-Up: “Claes Oldenburg and the Geometric Mouse.”

To read the history of the de Menils, William Middleton’s magnum opus of a biography is de rigueur.

Back to my visit and the hour at hand. A collection including galleries personally installed, display case by display case, by the incontestable Dominique de Menil 31 years earlier — a sacrosanct arrangement — had been altered.

What was the verdict?

Before I could convene with James, Armstrong, and Borden, I had to see for myself.

Entering the ‘New’ Menil

As I approached the promenade to the Menil, a sign announced its reopening. During the museum’s six-month closure, Rabinow had a coterie of staff braving humidity and elements to man a front desk outside, to direct visitors to alternate destinations on the Menil campus: the Cy Twombly Gallery, Byzantine Fresco Chapel, the Dan Flavin illuminated installation at Richmond Hall.

Unlike massive museum institutions in most American cities and also in Houston, guards at the Menil greet visitors as friends, and those working the front desk are not merely workers but trusted keepers of the legacy of art and activism fostered by its founders.

Foremost among these is Thelma Smith. When I saw Smith stationed once again at the front desk, I knew instinctively that this new iteration of the Menil would be reverently conceived and reveal new insights into artworks across time, into today.

I spent the final minutes of the late afternoon — the golden hour from 6 to 7 pm — at the museum and was one of the last visitors to depart. Then I joined my friends at Bistro Menil to compare notes.

We all concurred that the new installation creates a fresh dynamic between the artwork and Piano’s architecture.

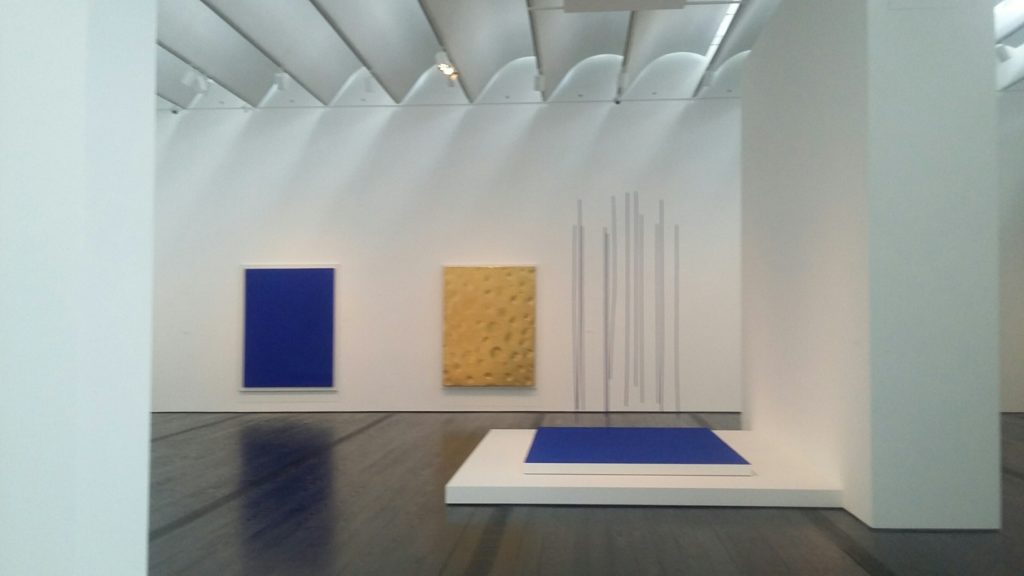

Borden singled out the joy of finding favorites (an Etruscan lion and the Sumerian Prince of Lagash holding court in the ancient art wing) amid new discoveries: a medieval tapestry depicting a unicorn; the Tinguely machine that moves its creepy, Surreal limbs every day at 12:15 pm; and a riveting and sublime Yves Klein.

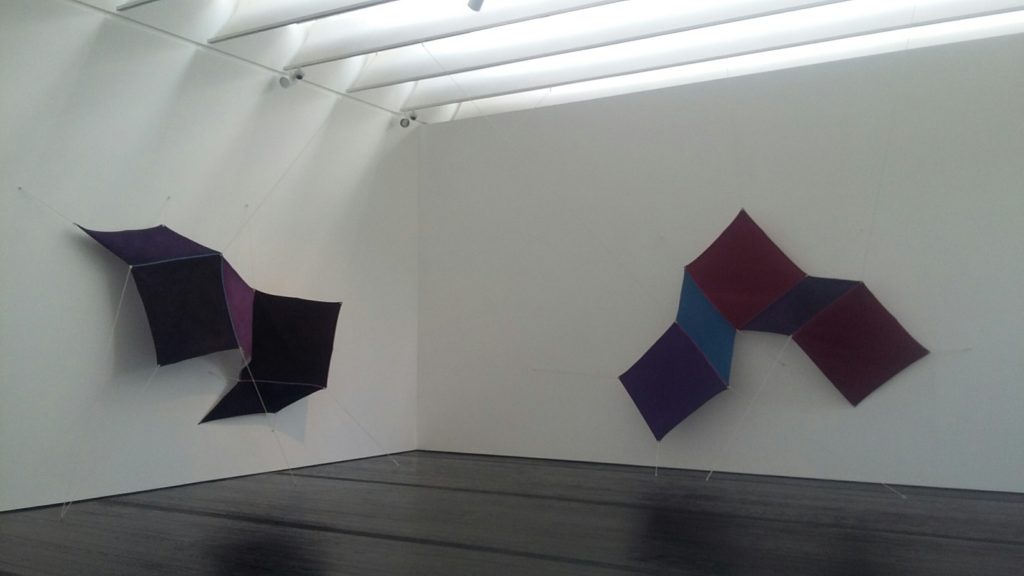

James and Armstrong both praised the museum’s bow to inclusion by showing women artists, which Armstrong called “beyond tokenism.” James singled out works on paper by Lee Krasner, Sonia Gechtoff, and Texan Toni LaSelle, as well as a mosaic by Jeanne Reynal, as notable finds in the renewed modern and contemporary galleries.

We all missed the Warhols and the classic Rauschenbergs, even though two early (and atypical) Rauschenbergs were represented.

Our quartet discussed the dramatic Frank Bowling, a painterly abstraction where luscious neon color melds with imagery, the sole work in the museum’s entrance gallery. The African-born British artist, who has been knighted by the British government, was recently discovered by the American museum world — showing, for example, at the Dallas Museum of Art and concurrently at a booth at the Dallas Art Fair in 2015. But the de Menils were early on Bowling, collecting his work in the 1970s, decades before the rest of the U.S. museum powers caught on.

Theaster Gates’ coiled fire-hose sculpture packed a punch, alluding to the Civil Rights movement. (We all missed the Pop Art but do agree that our time doesn’t seem right for its lighter moments.)

The Surrealism galleries were gauged successful but perhaps too pared-down, needing more layers; I personally missed the labyrinth arrangement of the former galleries but was happy to bask in a trove of Max Ernsts, one of the touchstones of the collection.

The haunting, hermetic Witnesses gallery is there in its glory, including the iconic desk and its contents that belonged to Mrs. de Menil, complete with Mickey Leland campaign buttons.

Word on the street has been glowing for the renewed museum — even among tough critics — and included adjectives such as “pure.”

The redux has also created an outpouring among the community, as well as renewed interest in the quiet and intense conversation provided by the museum’s artworks.

By 7 pm Sunday, I’d been among the 4,516 to make a pilgrimage to the Menil during its first weekend back.

Under a rising Magritte moon, all seemed right with the world once again.

Scroll through our slide show for top moments at the renewed Menil.

_md.jpeg)