A Lost English House Gets Reborn as One of Tony Highland Park’s Most Stunning Homes: How a Grand Drawing Room Traveled 6,000 Miles and Became a Star Interior Designer’s Greatest Treasure

BY Rebecca Sherman // 11.29.17In 1998, Joseph Minton attended a cocktail party at the Preston Road home of Highland Park matriarch Evelyn Jones. Everyone was gathering there for drinks before heading off to Nancy Hamon’s 80th-birthday bash at the Dallas Museum of Art, an elaborate costumed affair with an Arabian Nights theme, for which Hollywood set designer Tony Duquette had trucked in eight semis full of props and costumes.

Minton was appropriately dressed for the exotic evening in a tux and a white silk turban festooned with a diamond and turquoise pin. He stepped through the foyer into the main room and looked around. Women were elegantly draped in colorful silk saris and turbans, including his companion for the evening, the antiques dealer Betty Gertz, who wore a turban with a spinning cobra as decoration.

“But I didn’t pay any attention to the people,” Minton says. “My eye was immediately drawn to the room’s paneling and carved pilasters. I remember looking up at the Corinthian capitals.”

The beautifully patinated oak paneling enveloped the double-height room, and a fire roared in an enormous fireplace. Minton, an interior designer who splits his time between offices in Fort Worth and his longtime Dallas shop, Joseph Minton Antiques, noted that the mantel was ornately carved from rare, pure-white statuary marble, the kind from which Michelangelo summoned his Renaissance masterpiece David.

The room reminded him of the magnificent 18th-century halls he often visited in England while stationed there as an Air Force lieutenant during the Cold War. Almost every year since 1971, he returned to England to buy antiques, and he’s provided English antiques and interiors for top-drawer Fort Worth clients such as Anne and Charles Tandy, Bob and Pat Schieffer, and the Fortson family. Minton knows his stuff: This was no ordinary room. But there was no time to investigate, as everyone rushed off to Hamon’s party.

Years went by, yet the house never left his memory. “It haunted me,” he says. “I had no idea that I’d be living in it one day.”

Fast forward to 2003, when Jones (who passed away in 2011) had put the house up for sale. Minton wasn’t in the market to buy a new house. He already had a large home in Fort Worth and shared an apartment in Dallas on Turtle Creek with his longtime partner, Kevin Peavy, the director of Joseph Minton Antiques. Peavy recalls the night five years earlier when Minton came home from Nancy Hamon’s party gushing — not about the gala’s lavish costumes and sets, but about the mysterious ancient room he’d seen at Evelyn Jones’ house.

“He was raving about this incredible old room, with its high ceilings and wood paneling, that was such an unexpected surprise, almost like a secret room,” Peavy says. “He kept saying what a perfect house it would be for us.” The matter was settled; they just had to buy it.

The Lost Houses

Known as the Lost Houses, hundreds of England’s ancient country houses and ducal palaces were demolished in the first half of the 20th century, having fallen victim to changing times and rising taxes. Wingerworth Hall was one such house. In 1920, Major William Hunloke put his family’s historic estate up for auction, hoping to find a buyer.

Completed in 1729 and set on 5,340 acres north of London in Derbyshire, the stately 22-bedroom manor failed to sell and was torn down in 1929. Several of its rooms were salvaged intact by the London auction house Robersons of Knightsbridge, who took the oak drawing room, library, and large staircase. As a compendium to the sale, Robersons published a catalog documenting these rooms, along with rooms from other estates in black-and-white photographs and detailed descriptions. One stood out: the lofty oak drawing room with its 16 fluted Corinthian pilasters and carved statuary-marble fireplace.

As you may have suspected by now, it was this oak drawing room that ended up more than 6,000 miles away in Dallas, inside the house on Preston Road. But how? The trail had gone cold in the 1930s after the Robersons’ sale.

Once they moved into the house, Minton began researching the room’s history and sent photos of it to a cousin in England. The photos made their way to professors studying lost English country houses, who were friends of the family.

“I didn’t think much would come of it, but a month later my cousin called and left a message,” Minton says. “I nearly went through the ceiling.” Minton’s room was identical to the oak drawing room from Wingerworth Hall.

“I started Googling and found all these books and original auction catalogs on Wingerworth,” Minton says.

The hall, along with its oak drawing room, was carried out by one of the most prolific and noted architects and master builders of the era, Francis Smith of Warwick. Smith had also worked on aspects of Chatsworth House, the legendary residence of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, just 15 miles away from Wingerworth.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, about the time Wingerworth was demolished, wealthy Americans were snapping up salvaged rooms for their newly built houses. Few rivaled the consumption of such architectural specimens as William Randolph Hearst. The flamboyant newspaper publisher dispatched agents across Great Britain to acquire hundreds of ancient rooms to be installed at Hearst Castle, his hilltop mansion in San Simeon, California.

Wingerworth’s oak dining room was crated and shipped over for this purpose, but like many rooms Hearst bought, it was never used. It languished in storage for years, until Hearst’s dwindling finances forced a sale in 1941 of many of his acquisitions, including the oak drawing room, at an auction organized by Hammer Galleries in New York. Dalva Brothers Antiques in New York purchased the drawing room, and some years later, Dallas architect Wilson McClure, a longtime client of Dalva, acquired it.

Wilson McClure made a name for himself designing charming cottages in West Highland Park during the ’30s and ’40s. As his reputation grew, he built larger, more prestigious houses throughout the Park Cities and Preston Hollow, many of them in the Georgian style, and others with a Texas modern bent. In 1950, he built a two-bedroom 2,400-square-foot bachelor home for himself on Preston Road. It’s compact, but the classical facade is beautifully proportioned, with massively scaled windows centered under an early Greek pediment design. In back, McClure designed modern, double-height sliding glass doors.

Set on a large terraced lot with a creek below, the house’s big windows give the house an indoor-outdoor feel, and its thick concrete construction and double-pane windows — both advanced materials for the time — were designed to block traffic noise from Preston Road.

Most significantly, McClure placed the 300-year-old oak drawing room, which he’d brought down from New York, prominently in the center of the house. He lightened the dark oak by bleaching it — a process that included closing up the room for weeks to let the finish season in the heat. The resulting pale wood was a chic contrast to his high-gloss, black- painted wood floors. At 16 feet high, and 20 by 29 feet in size, the oak drawing room is proportioned exactly as it was at Wingerworth.

A Drawing Room’s Secret Legacy

While there would only ever be one 300-year-old oak drawing room, McClure modeled many of his later and more grand houses after his bachelor pad, which was a sort of opera set filled with theatrical effects. There were many stylish aspects to emulate, including its round dining room, whose walls are covered in a hand-painted pastoral scene on canvas. He was also known for designing invisible jib doors flush to the walls; there are a number of them in this house.

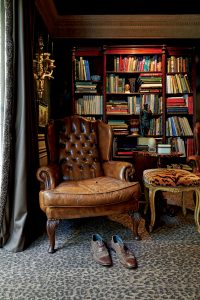

The most notable one leads from the round dining room into the kitchen and is a feat of engineering, as it lays imperceptibly within the curved walls. The bedrooms are tiny by today’s standards, and the smallest is located at the top of a steeply pitched creaky staircase. Even though the house has changed hands numerous times, its architecture and footprint have remarkably remained unchanged.When Minton and Peavy moved in, their tweaks were minimal and cosmetic, such as repainting the black wood floors. The library walls and ceiling were refinished in a gleaming tortoise-shell lacquer, applied by artisan Shaun Christopher, who layered 18 coats of lacquer to achieve the dramatic effect. Christopher also faux-finished molding in the library and the walls of the master bedroom to mimic the bleached oak wood paneling of the drawing room. The master bedroom ceiling was silver-leafed to help bounce light, and a pair of invisible jib doors hides behind mirrors and faux-finishing.

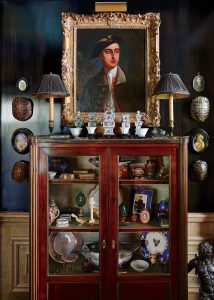

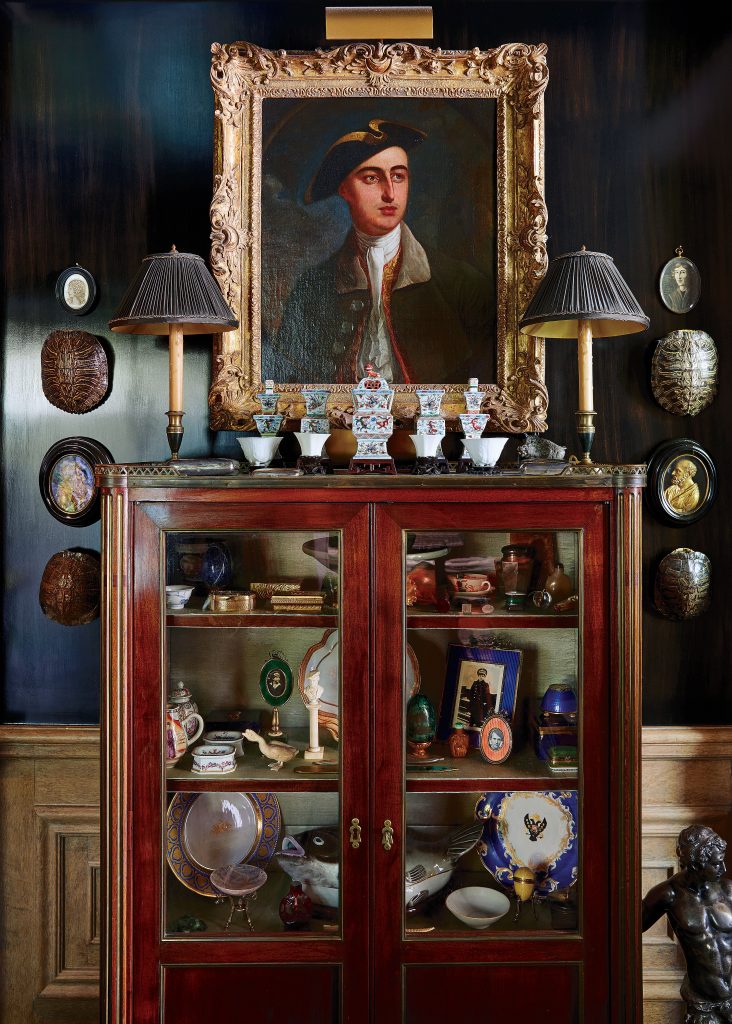

McClure’s exquisite architecture is the perfect backdrop for the pair’s antique furnishings and Minton’s large collection of Hatcher shipwreck blue-and-white Ming dynasty porcelains, much of it purchased from Betty Gertz’s store, East & Orient. While Peavy’s preference and expertise lies with rare French antiques, Minton gravitates to the simpler look of furniture produced in England, where he has spent so much time. Still, their combined furnishings fit perfectly inside the house and look as if they had always been a part of the oak drawing room.

“We didn’t need to buy anything new, as everything miraculously fit,” Peavy says.

An 18th-century French writing desk with a worn leather top and ormolu decoration stakes its claim under the large windows in the oak drawing room, attended by a pair of Louis XV-style leather chairs. Hung high is a pair of 18th-century gilt French boisserie panels and an 1865 English gilt mirror.

Minton brought some favorite pieces from his former New York pied-à-terre, including the comfortable ivory-linen-slipcovered sofa. The large glass-and-iron coffee table in front of the fireplace is a contemporary piece from the Minton-Corley Collection, and the table behind the sofa is 18th-century Irish mahogany, which originated from Loyd Paxton. There are period Queen Ann chairs with exquisite original needlework upholstery; a large pair of blue-and-white pots from a Drouot auction in Paris; a rare silver-leaf Italian grotto chair from the 18th century; and a small gilt-bronze ormolu table by the preeminent French cabinet maker of the 19th century, Paul Sormani.

The dining room includes a walnut table from the early 1800s or earlier, surrounded by dazzling 18th-century Italian gilt chairs upholstered in parrot-green Hermès shoe leather. A 1970s plaster console in the style of Serge Roche holds antique crystal globes, while an Adam-period pedestal holds a classical-period Roman bust. Minton and Peavy brought back a pair of George III bookcases from the Paris flea market for the library; they’re filled with books on architecture, history, and design. An old English tufted-leather chair in the library is their terrier Sassy’s favorite place to curl up.

In 2010, Joe Minton and Kevin Peavy traveled to England for an unprecedented sale of treasures accumulated in the attics and stores of Chatsworth, held by Sotheby’s. Before he left, Minton tucked a photo of his marble fireplace into his jacket pocket. They had invited friend and former Dallasite Jerry Hall — the ex-wife of Mick Jagger and newlywed to Rupert Murdock — to come with them to the auction. Afterwards, the Duke of Devonshire invited them to lunch in his private quarters.

“We were directed upstairs into the dining room,” Minton says. “As we passed through a sitting room, I looked to the left, and there was a fireplace mantel exactly like ours.” He couldn’t wait to get a closer look.

The group retired to the sitting room after lunch, and Minton sat next to Bill Burlington, the 12th heir of the Duke of Devonshire.

“I told him we had a room from Wingerworth Hall, which they knew all about, as the Duke’s aunt had married one of the Hunlocks, who owned Wingerworth.” Minton pulled out the photo of his mantel and showed it to the Duke and his son.

“Oh, your fireplace is prettier than ours,” the Duke exclaimed.

While the Duke’s mantel has a center plaque that was an unadorned slab of colored marble, Minton’s center plaque is a stunningly carved depiction of the goddess Diana. The plaque has been attributed to Edward Poynton of Nottingham, the favorite carver of Francis Smith of Warwick, who carried out work at both Chatsworth House and Wingerworth Hall.

The connection between the two great noble houses is awe-inspiring.

“It’s remarkable how the oak drawing room traveled from 18th century Derbyshire England to 21st century Dallas and into my house,” Minton says. “My favorite place in the world is lying down on the sofa, looking at the oak walls with the fire going.

“I used to think I’d have to be in England to see a room like this — I never imagined I’d have one in Dallas.”

_md.jpeg)