Dallas’ Secret House of Love: After His Partner’s Death, a Famed Designer Makes Their Dream Home Live On

BY Rebecca ShermanLoyd Taylor in the front courtyard. In the entry, objects from Tibet and India surround a Ming Dynasty wine table.

Loyd Taylor is waiting out front when I pull up, with the carved wood door to a massive, vine-covered wall propped open. He ushers me inside, and we walk through an unruly courtyard garden withered by winter, past an ancient towering bronze pagoda and towards the small house where Taylor has lived for 15 years.

Built in 1988 in Dallas’ Oak Lawn Heights by a man who owned a glass-manufacturing company, the house is almost completely transparent. Its L-shaped glass exterior reveals deep cinnabar-hued rooms laden with jeweled Tibetan religious relics and books. It may not be a high mountain lamasery shrouded in mist, but there’s still an otherworldly Lost Horizon feel to this discovery, with its walled garden and secreted house brimming with rarities.

“People have no idea what’s back here,” Taylor says. “You think you’re going to walk into a room when you go through that big courtyard door — but it’s a surprise.” Surprises make people happy, he notes, and this house has brought him joy since he and his late partner, Paxton Gremillion, bought it in 2002.

Inside, Taylor’s house manager, Paul Sanchez — who also has maintained the Loyd-Paxton antiques showroom for the past 25 years — serves us sparkling water and tea on a silver tray while Taylor walks me around. Daizi, a 7-year-old rescued greyhound, trails behind us, her nails clicking on the hardwood floors.

Taylor looks down. “One last thing I’d like to do is stain these floors dark,” he says. “But it’s such an upheaval. I’ll leave that for another time.”

Taylor is all too familiar with upheaval. Gremillion was diagnosed with cancer shortly after the couple moved here, and he spent a decade battling the disease. Taylor took over much of their interior design work, leaving little time or energy to decorate their new abode.

Books and artifacts remained unpacked in boxes and stacked in rooms, and furniture was stored in a warehouse. The dining room served as a makeshift office, with only the bare essentials — a table, two chairs, and a fax machine. For 10 years, Taylor remembers, “We were literally just camping out here.”

Six months after Gremillion’s death in 2014, Taylor finally began the slow process of unpacking and editing. He considered closing the showroom on Irving Boulevard but kept it open. He sold off what he didn’t want and kept his favorites; he bought new furniture and had old pieces recovered. The house sprang to life, becoming the home he and Gremillion once envisioned.

“I remember when we first saw the house,” says Taylor. “Paxton just opened that front door and said, ‘This is it.’”

Loyd Taylor and Paxton Gremillion met in 1959 at the University of North Texas, where Gremillion studied concert piano and Taylor pursued design. They were inseparable. In 1960, they opened an antiques showroom, Loyd-Paxton, on Sale Street in Dallas, fueled by a collection of extraordinary Italian furnishings consigned to them by a globetrotting opera teacher from UNT.

Their reputation and inventory grew quickly, and soon they had clients across the globe. In 1985, the store relocated to its opulent longtime location on Maple Avenue, where they lived above the shop, like European antiquarians.

In its heyday, Loyd-Paxton was a candy jar of Asian and European rarities, frequented by an international jet set that included Sir Elton John and Saudi Prince Faisal. For his palace, the Sultan of Brunei bought crates of gilt bronze tables with malachite tops, semiprecious mineral objects, and rock-crystal lighting. He outfitted his private plane similarly, and custom cabinets were made to secure furniture and objects until after takeoff.

Rare French antiques from Loyd-Paxton made their way into Versailles when it underwent renovations, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York purchased pieces, including a dazzling Louis XIV Boulle desk, which had been owned by the Sun King himself. Prominent local families such as Juanita and Henry S. Miller Jr. and Fort Worth’s Martha Hyder hired Loyd-Paxton to design their homes. Architectural Digest often featured the couple’s projects, which were famous for their glamorous interiors and dash of theater.

Loyd-Paxton created total environments that were much more than mere rooms. “So many decorators just do curtains and carpet and furnishings,” says Taylor. “We created a cocoon — or a piece of art.”

Clients demanded excitement, and they obliged with spaces layered in mirrors and lacquer, and large, statement-making furniture and art. “Paxton and I always created illusions,” Taylor says.

Once, when they couldn’t find the perfect reflective paint for a client’s penthouse walls, the job was done with 50-gallon containers of pearlescent nail polish from Revlon. Interior design wasn’t just about making something beautiful, it was a chance to escape into another world.

In 1972, they sheathed their own apartment in the Athena high-rise in black piano lacquer, black marble, stainless steel, and mirrors. “It was a total fantasy,” Taylor says. “I was a dreamer, and so was Paxton.”

In a way, the glass house where he now lives takes Taylor back to his design roots as a student in the 1950s — the Bauhaus movement in full swing. “The house is a very simple statement,” he says. “I’ve tried to respect that.”

In every direction, glass walls and doors overlook peaceful, Zen-like courtyards and a backyard koi pond surrounded by potted ornamental maples. “I love the openness and its connection to nature,” he says.

Rather than blocking views with furniture, Taylor focused on displaying beautiful Asian objects and books on stunning cinnabar-hued interior walls. There’s a smattering of antique lacquer furniture and upholstered mid-20th century pieces to keep it all comfortable. “I could have gone more contemporary,” he says, “but I liked the idea of surrounding myself with old things … You get a certain vibration — a chit-chit-chit — from things that people have loved and lived with. They tell you about the life and the people who owned them.”

The stories his collections tell span centuries and continents, much of them originating from ancient Chinese Buddhist temples and Tibetan lamaseries, whose contents had been pillaged and dispersed throughout England and India.

The couple started buying pieces in the 1970s and ’80s, and over the years sold much of it back to the Chinese. What Taylor has held onto is scarce and precious, including dozens of 19th-century religious artifacts, such as gilt copper Guanyin statues and mandalas, many studded with rubies, opals, sapphires, coral, and turquoise.

There are ancient, gnarled spirit stones, mounted on pedestals like modern sculpture. A glass case displays impossibly large faceted gemstones such as fluorine and smoky quartz. On his desk, a circa-1950 gold Tiffany & Co. box is topped with a huge cut and polished citrine. “I’ve always had a fascination with minerals,” he says.

His antique Asian furniture includes a pair of early-19th-century lacquered cabinets, similar to a pair in Consuelo Vanderbilt’s New York apartment, which he admired in Vogue as a child. A pair of cinnabar Burmese altars have been turned into side tables, and newly acquired furniture, such as Chinese Chippendale-inspired chairs from the mid-20th century, update the Asian influence.

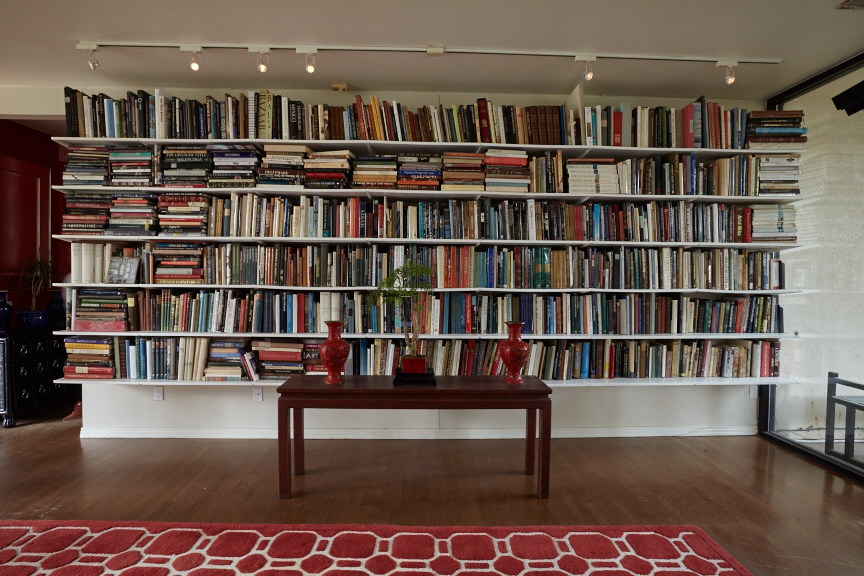

After Gremillion died, Taylor sorted through hundreds of books they’d amassed together over 50 years. Shelves in the living room now hold what’s most meaningful to him: volumes on decoration, jewelry, minerals, fashion, Texas history, biographies, and movies.

As Loyd Taylor explains it, the house is not so much a reflection of who he is, as it is an edited version of a half-century of life shared with Paxton.

“We did everything together, and when you share a space with someone for so long, they’re always a part of it,” he says. But clearing out the cobwebs of clutter and letting go is healthy, he adds. “I am me now — you know?”