Houston’s Roman Art Blockbuster Shines a Light On a ‘Good’ Emperor — Italian Museum Treasures Beckon at MFAH

Art and Life In Imperial Rome

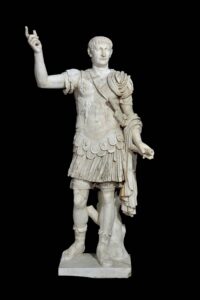

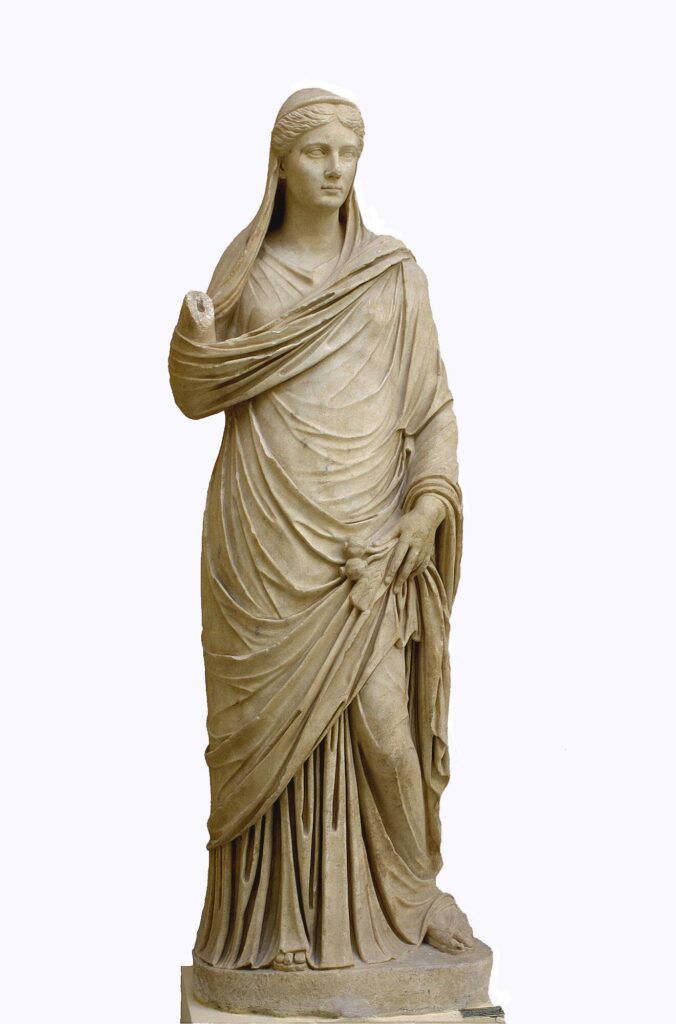

BY Leslie Loddeke //Statue of Trajan, Minturno, Italy, 2nd century, National Archaeological Museum, Naples (Image courtesy MFAH.)

What makes a great leader — one whose legacy will live on for centuries? The impressive new art exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston that inspires this question makes one contemplate the rich artistic legacy of Emperor Trajan, who ruled the Roman Empire at its height.

“Art and Life in Imperial Rome: Trajan and His Times” offers a rare look at those extraordinary times through a vast display of intriguing objects unearthed from that era.

The MFAH and the Saint Louis Art Museum joined forces to present the first major exhibition in the United States dedicated to the Emperor Trajan, whose nearly 20-year reign was characterized by stability, prosperity and massive expansion.

“This is truly a rare opportunity for U.S. audiences to experience spectacular objects from the glorious era of the Roman Empire,” MFAH director Gary Tinterow says.

Displaying 160 ancient objects from Italian museums, including handsome marble statues, intricate friezes and beautiful frescoes, the show explores the impact of Trajan’s reign on art and culture at the turn of the 2nd century A.D.

“The art and architecture of ancient Rome continue to inspire awe and ignite curiosity,” notes Min Jun Kim, the Barbara B. Taylor director of the Saint Louis Art Museum. Notably, the old St. Louis museum’s architecture, like many iconic buildings in that city, reflects its Roman influence.

Through explanatory labels and wall text, exhibition viewers learn a wealth of information about arcane objects. Look for the unguentaria, lovely little glass vessels that once held scented oils and powders; transport amphorae, terracotta containers for wine that were found at Ostia, the port city of ancient Rome; and a marble funerary relief of horses drawing a chariot in the Circus Maximus, the huge Roman arena where chariot races were widely attended, which Trajan extensively renovated.

The Man Behind The Emperor

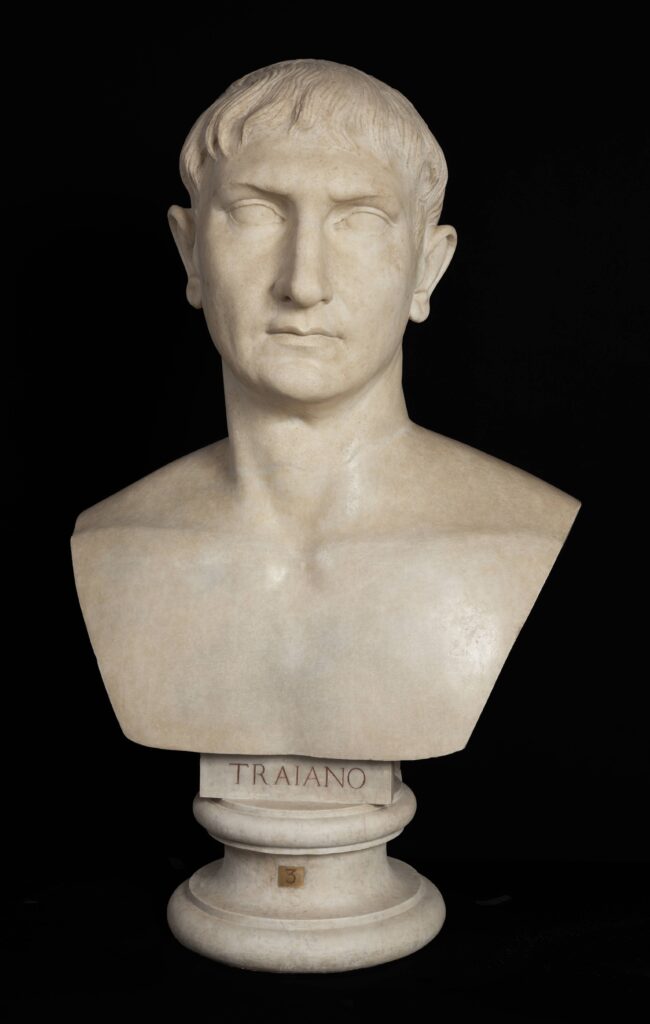

Who was this man, and what explained his rise to lasting acclaim as the second of the so-called Five Good Emperors of the Nerva-Antoine dynasty?

First, he was an outsider, the first of Rome’s emperors born outside present-day Italy, from a family residing in what is now Andalusia, Spain. From the show, we learn that Trajan’s military and imperial successes as soldier-emperor propelled him to popular fame.

Further, we learn that as ruler, Trajan granted citizenship and its rights to the people from the far-reaching provinces that his troops conquered, “expanding and fundamentally changing what it meant to be Roman.”

An active architectural innovator, Trajan initiated countless construction projects for the community. Those included an artificial harbor; Trajan’s Forum, a major meeting space; roadways and aqueducts; and civic structures like public baths and the Basilica Ulpia, once the largest and most opulent basilica in ancient Rome. He became famous and greatly appreciated by his people for such beneficial public works.

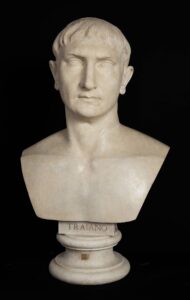

As we enter the exhibition, everyone is greeted by Trajan’s handsome marble image in a noble pose. He looks every inch the emperor as he leads an array of statues and busts of the patrician men and women who shaped the Roman world of his dynasty.

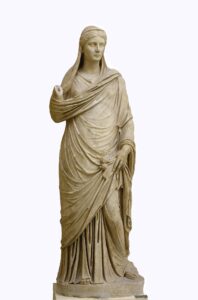

One particularly powerful women stands nearby. Look for the marble statue of the elegant Empress Sabina, the grandniece of Trajan who became the wife of Trajan’s successor and nephew Hadrian.

Women Who Shaped Rome

A wall text tells us that Trajan and his wife Plotina, did not have children. However, his dynasty continued through the women of his family, including his sister, her daughter and her granddaughter Sabina. Here, Sabina appears in the guise of Ceres, goddess of agriculture and prosperity, symbolized by the wheat and poppies in her lowered hand.

Following these pristine marble figures of Roman leaders, we find myriad artistic objects and decorative furnishings suggestive of their lifestyle. Inviting close scrutiny are the many elaborate friezes and frescoes, which often displayed mythological scenes and characters, like the Amazon warrior seen in a fresco from Pompeii. Everyday objects also featured this symbolism, such as a terracotta oil lamp from Ostia that features Fortuna, goddess of luck.

There’s an especially eye-catching Roman “Mosaic Pavement with Fish,” featuring three pairs of big, colored fish. This type of design appeared on dining room floors to indicate an abundance of food. Art was everywhere, as seen in the meticulous, obviously time-consuming craftsmanship of the objects throughout the galleries.

Fittingly, at the end of the exhibition we encounter a recreation of a section of Trajan’s Tower, whose extensive, ornate friezes chronicle Trajan’s successful campaigns against Dacia (now Romania) and which still stands today, soaring over 100 feet into the sky.

The endlessly fascinating objects on display are loaned from various museums including the National Roman Museum, the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, the Archaeological Park of Ostia Antica and the Vatican Museums.

The exhibition, which will move to SLAM next spring after it ends Jan. 25 in Houston, was curated by Dr. Lucrezia Ungaro, former director of the Imperial Forums Museum, Rome. The Houston show was co-organized by StArt and MFAH.

“Art and Life in Imperial Rome: Trajan and His Times” is on view at MFAH through January 25.