Artist Vincent Valdez Recasts America’s Evil Legacies in Houston Exhibition — Tackling The Klan, Lynchings and More At CAMH

From Provocative Portraits to Protest Anthems That Force Us to Reckon With The Forgotten

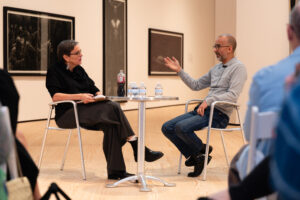

BY Ericka Schiche // 03.06.25Artist Vincent Valdez stands near his photorealistic oil on canvas painting "So Long, Mary Ann" (2019) during the public opening for "Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…" at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2024. (Photo by Tasha Gorel, courtesy Contemporary Arts Museum Houston)

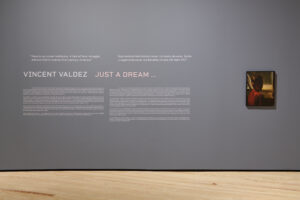

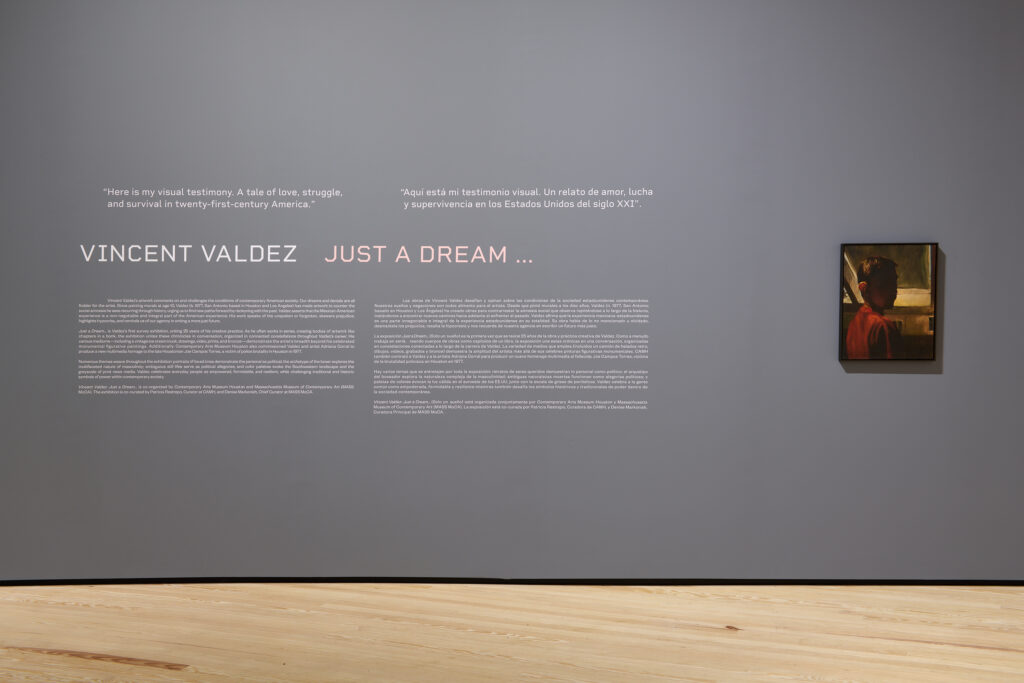

Vincent Valdez’s art confronts history with a piercing clarity, offering a Chicano perspective on struggles that remain relevant today. As he remarked during an exhibit walkthrough: “This story — this history — is not the past. The past is present.” Valdez reinterprets the idea of “What’s past is prologue,” bringing it into new dimensions. Currently on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through March 23, the “Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…” survey both enlightens and challenges viewers alike.

This exhibit continues the conversation about the Chicano Art Movement in Texas, following the 1977 exhibit “Dale Gás: Chicano Art of Texas,” which featured San Antonio’s Con Safo art collective. The Valdez exhibit is co-curated by Patricia Restrepo (CAMH) and Denise Markonish (MASS MoCA).

From San Antonio to Los Angeles

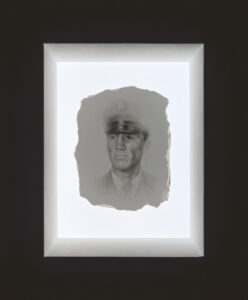

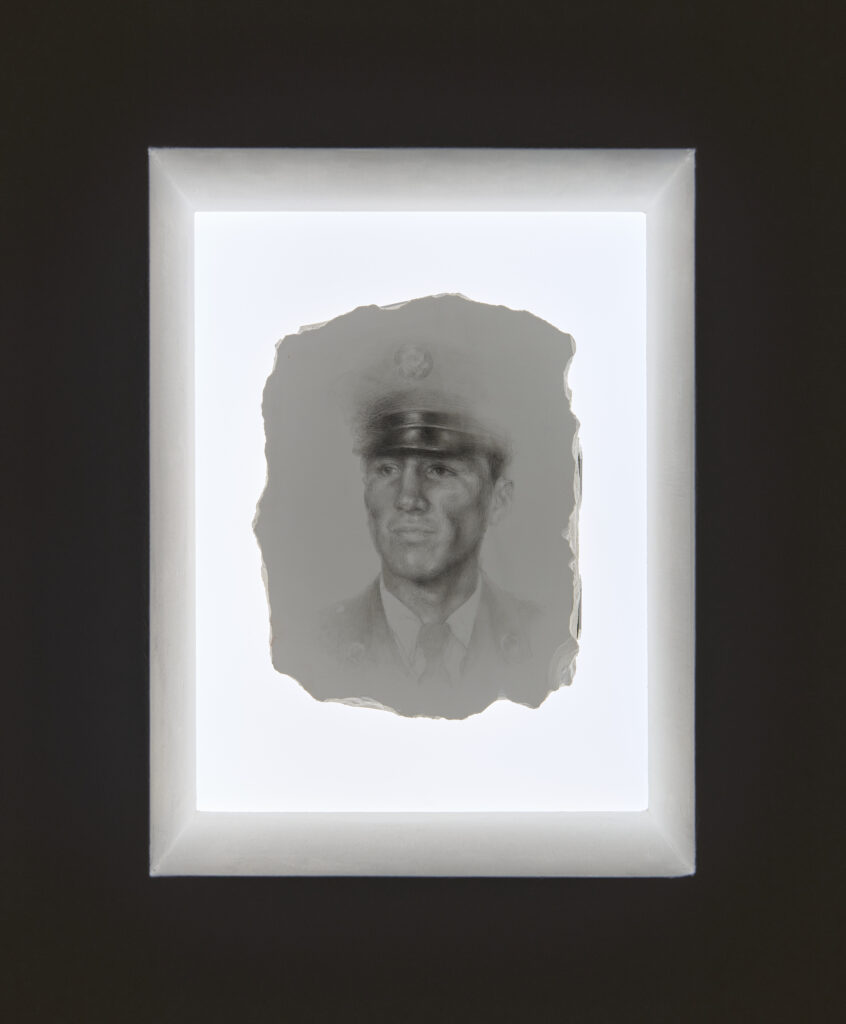

Although Valdez hails from San Antonio, he now divides his time between Houston and Los Angeles. His artistic journey began at the age of 10, and it’s clear that his roots have shaped much of his work. This CAMH exhibit includes his 2012 short film Home, which honors his hometown and his lifelong friend, 2nd Lt. John R. Holt Jr. In the film, a flag-draped coffin floats through San Antonio’s streets, adding a layer of personal tribute to the piece.

One of the most powerful works in the exhibit is Burn Baby Burn (2009). It resonates strongly given the recent wildfires that ravaged Los Angeles. This hyperrealistic oil painting depicts a panoramic, dystopian view of the city at night. The downtown skyline contrasts the eerie orange glow of wildfires. Valdez painted the scene from his Boyle Heights apartment.

The title also carries historical significance. Legendary radio DJ Nathaniel “Magnificent” Montague’s phrase “Burn, baby! Burn!” morphed into an anthem during the 1965 Watts Rebellion. Poet Marvin X’s Burn Baby Burn, published in Soulbook Magazine, also inspired leaders of the Black Panther Party.

Another major work in the exhibit, El Chavez Ravine (2005-07), recalls the forced removal of a Mexican-American community in Los Angeles to make way for Dodger Stadium in the 1950s. Valdez painted directly onto a 1953 Chevy Good Humor ice cream truck, with a video of a woman being forcibly removed from her home playing nearby.

A Legendary Chicano Perspective

Cheech Marin, a major figure in the Chicano art movement, recognizes Valdez as a key artist. Marin, half of the iconic 1970s to 1980s comedic duo Cheech & Chong, has collected art for decades. His collection of more than 700 artworks is housed at The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture at the Riverside Art Museum in California.

“Valdez is right up there at the top with the best of them,” Marin tells PaperCity. “He was influenced by masters of Chicano art like John Valadez, Frank Romero and Carlos Almaraz. He is a continuum of that line — the highest breaking wave of the new wave.”

Marin was first introduced to Valdez’s work by Richard Duardo, known as the “Warhol of the West.” Duardo mentored Marin and worked with artists such as Keith Haring, David Hockney, Chaz Bojórquez, Shepard Fairey and Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh.

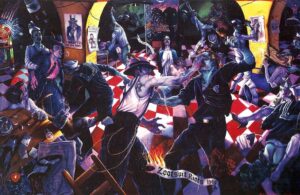

After Valdez graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, Marin visited him in San Antonio. This is when he first saw Valdez’s painting Kill the Pachuco Bastard! (2001).

For Marin, the work tells an important historical story. The 1943 Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles were a pivotal event in Chicano history (pachuco means “zoot suiter”). “The mayor and chief of police let sailors run rampant against the teenaged zoot suiters because they were flamboyant during an age of austerity,” Marin notes.

Marin’s defense of Valdez’s retelling of the Zoot Suit Riots is simple. “I said, ‘You know, every major museum I’ve visited around the world has some version of The Rape of the Sabine Women. This is the Chicano version.

“Because he focused on something historical as a new artist spoke volumes about his connection to history in that community. That he did it with such aplomb and technical virtuosity right off the bat — it’s astounding.”

Capitalism as a Canvas

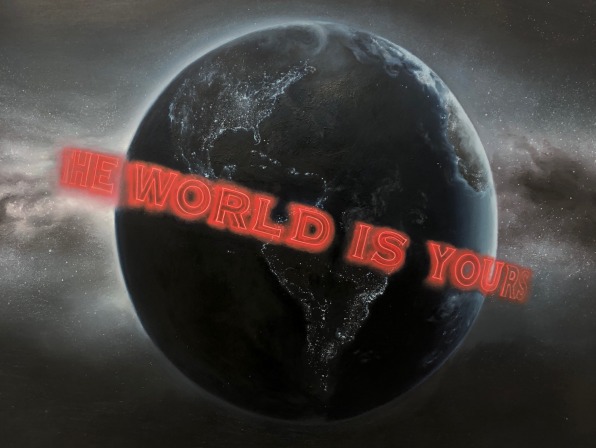

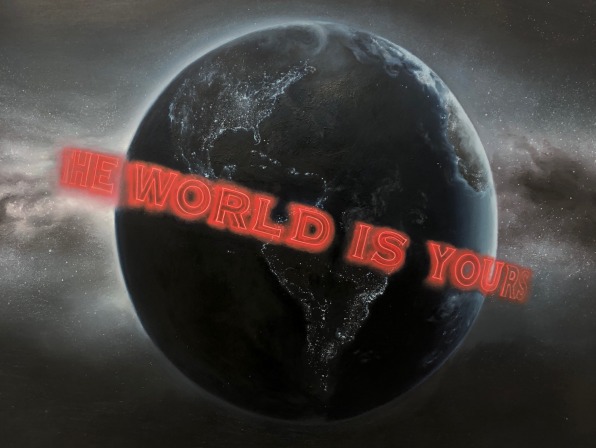

Valdez explores the failures and contradictions of capitalism in works like It Was Never Yours (2019). He draws inspiration from a key scene in Scarface when a young Tony Montana stares up at a blimp flashing the phrase “The World Is Yours.” Valdez notes. “It’s the story of an ambitious character who becomes unrecognizable due to power, greed and violence. I translated that into something almost like the opening sequence of a Universal Studios film.”

His reinterpretation of the Universal globe, with its red neon letters, offers an ironic take on earlier designs by artists like Eyvind Earle. The title itself conveys how capitalism’s promises often fail to deliver for the working class.

Houston Connections

Valdez’s adopted home of Houston also plays a significant role in this CAMH exhibit. The Hole/In Memory (For Joe Campos Torres) is a collaboration with artist and partner Adriana Corral. Made of gypsum, shells and soil from Buffalo Bayou, The Hole (2024) is inspired by the legacy of José Campos Torres, who was tortured by Houston Police Department officers and later died.

“What really sparked my and Adriana’s interest was how similar this story is to cases like George Floyd’s,” Valdez says. “It’s a powerful way to encourage others to realize this issue is urgent across American communities.”

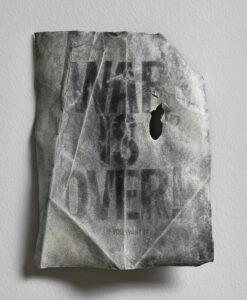

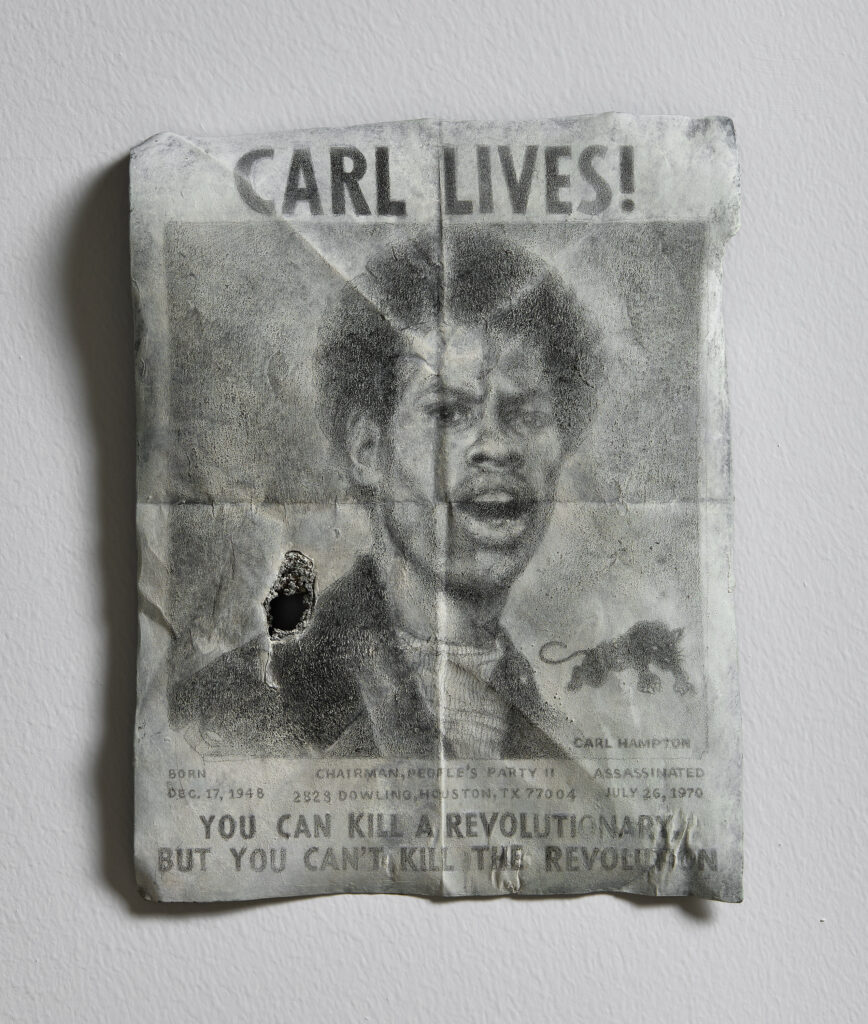

Following The Hole, visitors encounter Notes For a Future (2024), a series of bronze drawings. One of the drawings, which mimics crumpled paper, honors Carl Hampton. He was the leader of the People’s Party II — a precursor to the Black Panther Party in Houston. Hampton was assassinated by Houston police in 1970.

Recalling Painful Legacies

Valdez interrogates history by reimagining it in a contemporary context, addressing painful legacies like the Ku Klux Klan. His grisaille paintings of the Klan have sparked controversy, much like Philip Guston’s neo-expressionist works, which inspired Valdez. Guston painted the Klan from his own perspective in oil paintings such as Edge of Town (1969), Flatlands (1970) and The City Limits (1969).

During the 2020 George Floyd discourse, several art institutions delayed Guston’s retrospective, raising questions about art’s role in challenging society. In contrast, Valdez’s Klan-themed works were received without judgment. “Most people understood,” he says. “They were willing and ready to recognize, ‘Hey, what’s the big deal? We know what this is. This is a part of our American reality.’ ”

“The pushback mostly came from the media. It made me question whose perspective that was and who found it controversial,” said Valdez. “It revealed that white America still does not understand the role Mexican Americans play within our country. For the media to question whether I have the right as a Mexican American to paint the Klan is pretty absurd to me.”

Valdez reflects on the ongoing legacy of lynching, linked inextricably to the Jim Crow era, and how it affected other communities beyond the Black community. “I remember hearing about lynchings of Mexican American citizens and Mexicans as a kid in San Antonio,” he recalls.

Reinterpreting America’s Dark Legacy

The Strangest Fruit (2013) series, composed of eight oil on canvas paintings, is a poignant reminder of America’s dark history. Valdez began the series after finding Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, a book featuring haunting images of lynching postcards.

The paintings depict eight men in distorted positions, absent the noose typically seen in lynching images. The title Strangest Fruit references Abel Meeropol’s poem, written by the son of Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants who fled anti-Semitic pogroms. Meeropol adapted the poem into an anti-lynching anthem for Billie Holiday, who famously performed it at Café Society in New York City and recorded it in 1939.

“It was important to tell it with Billie Holiday’s adaptation of Abel Meeropol’s poem Strange Fruit because it was a reminder of solidarity between the Black and Brown communities in America. It’s a reminder that we are not alone in our struggles — they are very similar, both past and present,” Valdez says.

Valdez adapted the poem’s lines into English and Spanish, changing “poplar trees” to “pecan trees” to ground it in Texas. As he explains: “I presented it in the format of a corrido, a Mexican folk song used as a political instrument. But it was important to take this historic context from the late 1800s and early 1900s and re-tell it for the viewer through a contemporary lens.

“I asked myself whether, in 21st century America, the threat of the noose and its oppressive agents and forces had disappeared. How has the system repackaged and redistributed these threats in the form of mass incarceration, for-profit prisons, border policies, stop-and-frisk programs, broken education systems, biased justice systems, etc.?”

Over the years, music has been integral to Valdez’s work. The spirit of Lalo Guerrero, the unsung singer-guitarist who passed away in 2005, pervades the exhibit. Guerrero’s 1949 song “Los Chucos Suaves” captures the zoot-suiter era. Guerrero and Valdez also collaborated with musician Ry Cooder, whose Chávez Ravine album inspired Valdez’s El Chavez Ravine truck.

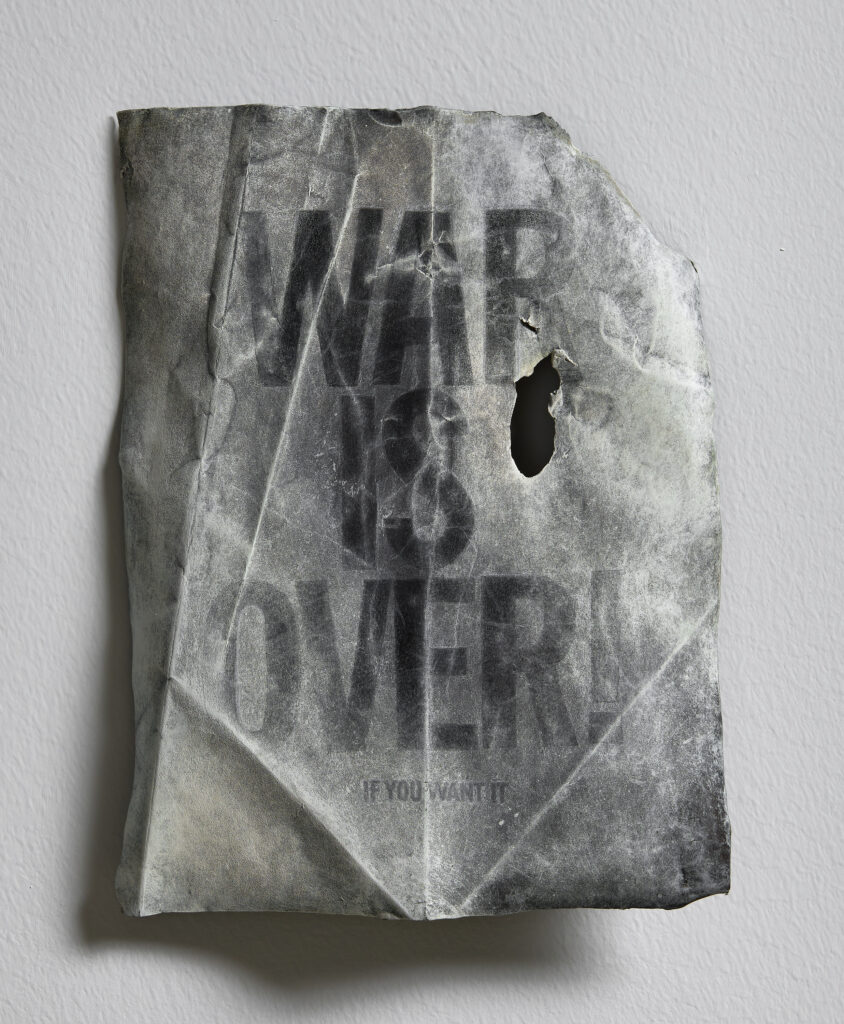

“It’s about America’s obsession with war,” Valdez says, referring to Cooder’s satirical song “Christmas Time This Year,” which features Valdez’s illustrations. These images, including a flag-draped casket, were taken from Valdez’s Excerpts For John, a series of works on paper.

Ultimately, Valdez hopes audiences will approach his work with an open mind. “My goal as an artist is to provide viewers with a sense of empowerment,” he says. “My intention is that people of any age or background can find a bit of themselves in the subjects I portray. That’s enough to get me back in the studio and to keep pushing forward every day.”

“Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream…” is on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through Sunday, March 23. Learn more here.

_md.jpg)

_md.jpeg)