Iconic Photographer Ming Smith Brings Invisible Subjects Into the Light With Houston Museum Exhibition, National Tour

Examining What It Means to be Black in America

BY Ericka Schiche // 09.29.23Ming Smith's "Self Portrait With Camera," 1989 (Courtesy Ming Smith Studio)

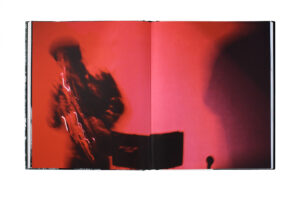

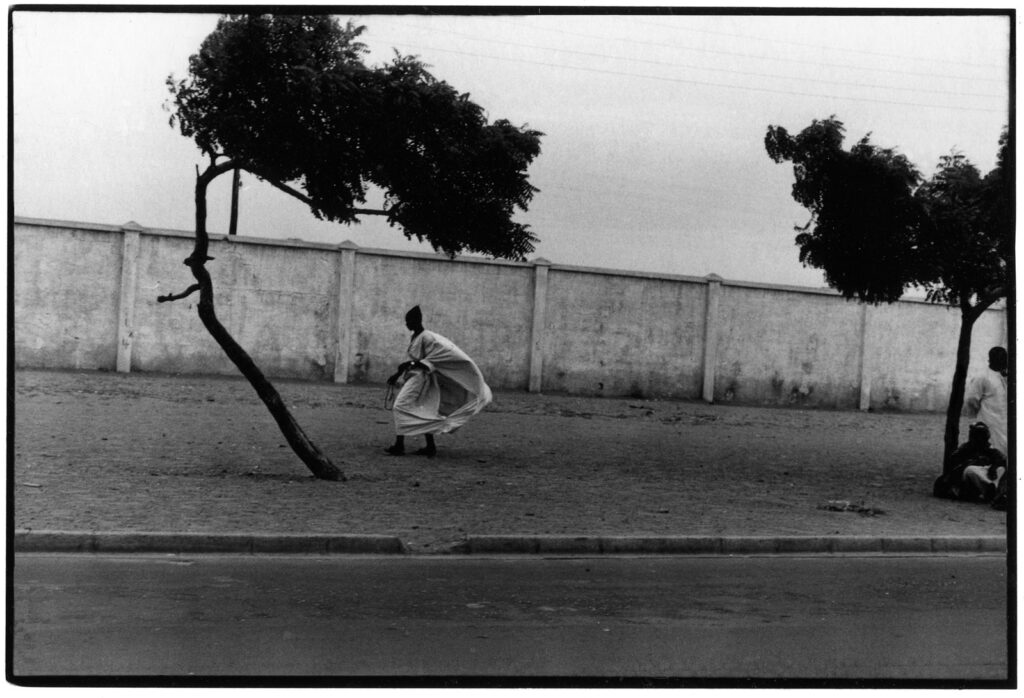

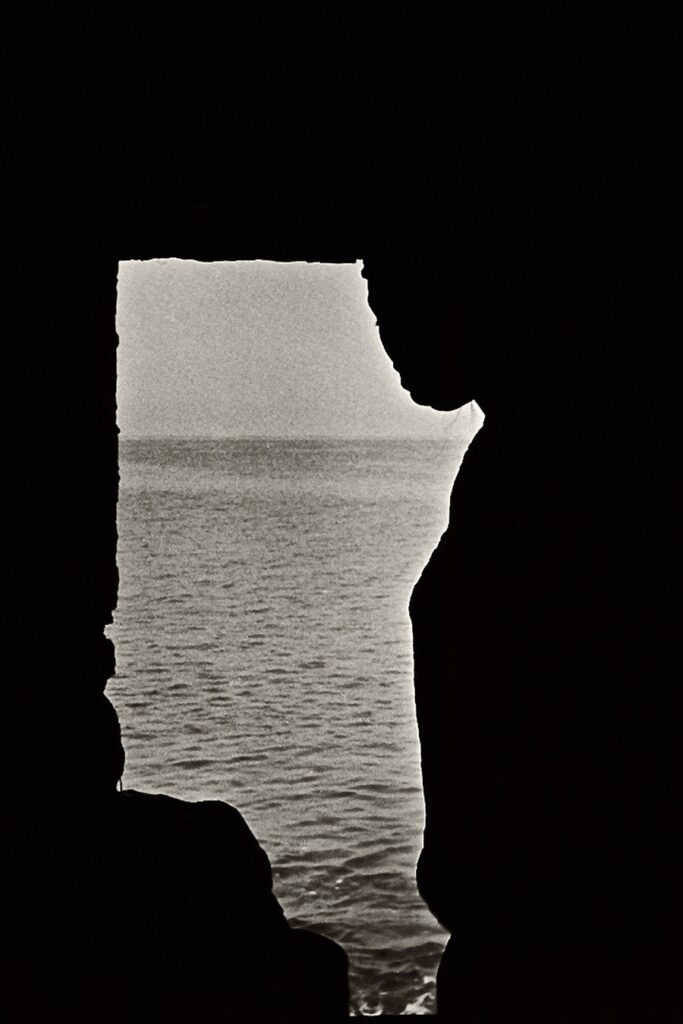

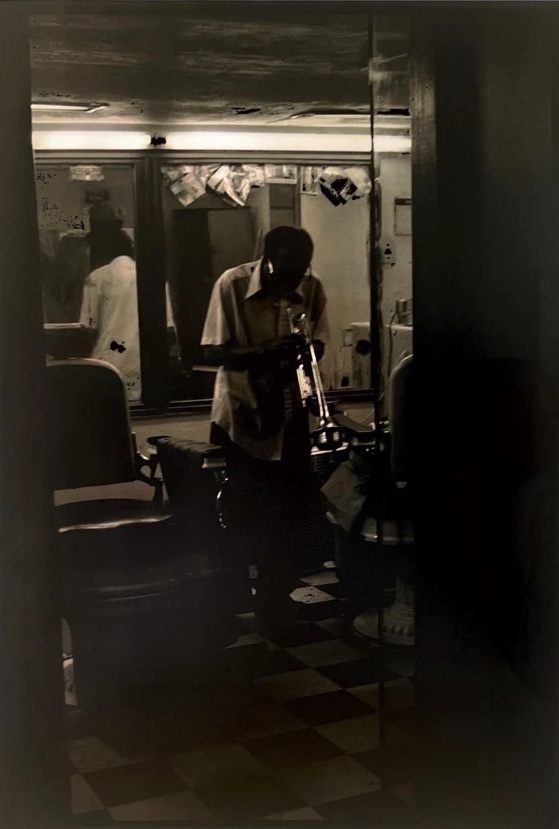

Capturing realism and milieus suffused with light while also establishing clarity is the objective of many working photographers. Ming Smith, however, prefers multiple exposures, dark environs, intentional blur and slow shutter speed.

Still, the legendary and inimitable photographer embraces light as an important element, even in a metaphysical sense. Like Brassaï and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Smith has also mastered capturing surreal day or night scenes and poetic realism.

What defines Ming Smith’s work above all else, though, is the experiential realities of Black people. Her photos pose a recurring ontological question: “What does it mean to be Black?”

Showing at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through this Sunday, October 1, “Ming Smith: Feeling the Future” reveals a complex, stylish and intelligent body of work. This exhibition, defined by elements of Afrofuturism and Black culture, was conceived by gallerist Janice Bond and curated by James E. Bartlett.

It is also a retrospective, presenting work by Smith from the 1970s to present day. Combined with earlier brilliant exhibitions at Art Is Bond and Barbara Davis Gallery, both of whom represent Smith in Houston, “Feeling the Future” reveals a rich subject matter and the intensity of Smith’s stunningly beautiful images.

Interviewed by Greg Tate for Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph, Arthur Jafa describes the technical prowess showcased in Smith’s oeuvre.

“Her capacity to control the dual technical strategies and abnormal technical strategy of slow shutter speed and the flattened tonal range to erase the typical relationships between figure and background, foreground and background, are unparalleled,” Jafa notes.

Born in Detroit and later living with her family in Columbus, Ohio, Ming Smith’s earliest exposure to photography began with her parents. Her father, who loved photography, painting and sculpture, owned an Argus C3 camera. Her mother owned a Kodak Brownie camera.

“Maybe it was just instinctive, because I did photograph the students in my kindergarten class,” Smith tells PaperCity. “I borrowed my mother’s Brownie and I took photographs. I definitely loved photography.”

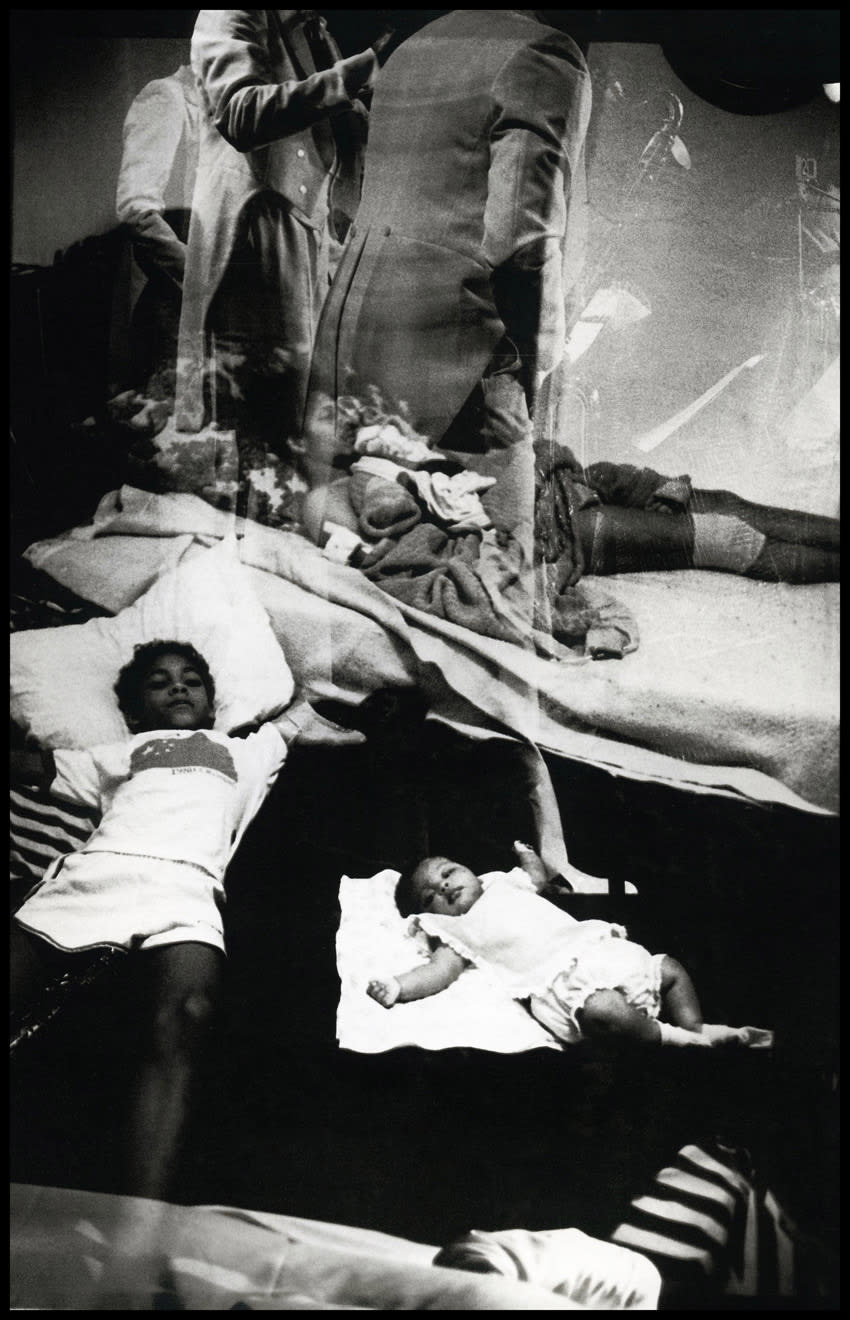

This early affinity paid off in Smith’s adulthood, when she captured images of childhood in Harlem. Her Oolong’s Nightmare, Save the Children (For Marvin Gaye) (1979) establishes an urban, working-class surrealism within the context of children’s quotidian experiences. What’s It All About (1976) reveals a young boy sitting far away from adults in Harlem.

It is an existentialist moment, one suggesting how children engage in a solitary incessant journey towards discoveries in life.

Smith attended Howard University in Washington, D.C. While there, she captured one of the most important figures in sports history.

“I photographed Muhammad Ali — his name was Cassius Clay at the time — on the steps of Founders (at Howard),” Smith says. “I lost that image.”

After graduating in 1973, Smith moved to New York City. She describes her first New York City neighborhood, the West Village, as a liberating, non-judgmental zone where she could be herself.

“I used to walk around in my jeans and a bomber jacket, and my hair wild,” Smith says. “And my mother was like, ‘Can’t you do something with that hair?’ It was real basic like that.”

Describing the people of the Village, many of whom were members of the LGBTQ+ community, Smith notes: “They were about free spirit and being free to be you. And I loved that. I LOVED that in the Village.”

During her early days in New York City, when she was a model and dancer, Ming Smith walked the streets carrying a Rolleiflex — a camera famously used by photographers such as Robert Capa, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Gordon Parks and Diane Arbus.

Much like the photos taken by Weegee, Robert Frank and William Klein, Smith’s work has a cinematic quality. And, like the New York City-focused Weegee, Smith enjoys employing a film noir edge, but with more of a surreal atmosphere.

The cinematic quality of Smith’s work inspires a look back into New York City film history. The idea of being alone in the city, captured in the Paul Fejös-directed cult classic Lonesome (1928), drives Smith’s vision. Despite describing herself as a loner, Smith also thinks of herself as a people person with a camera.

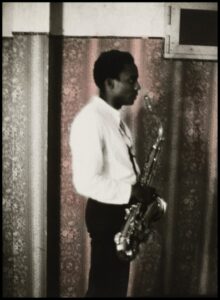

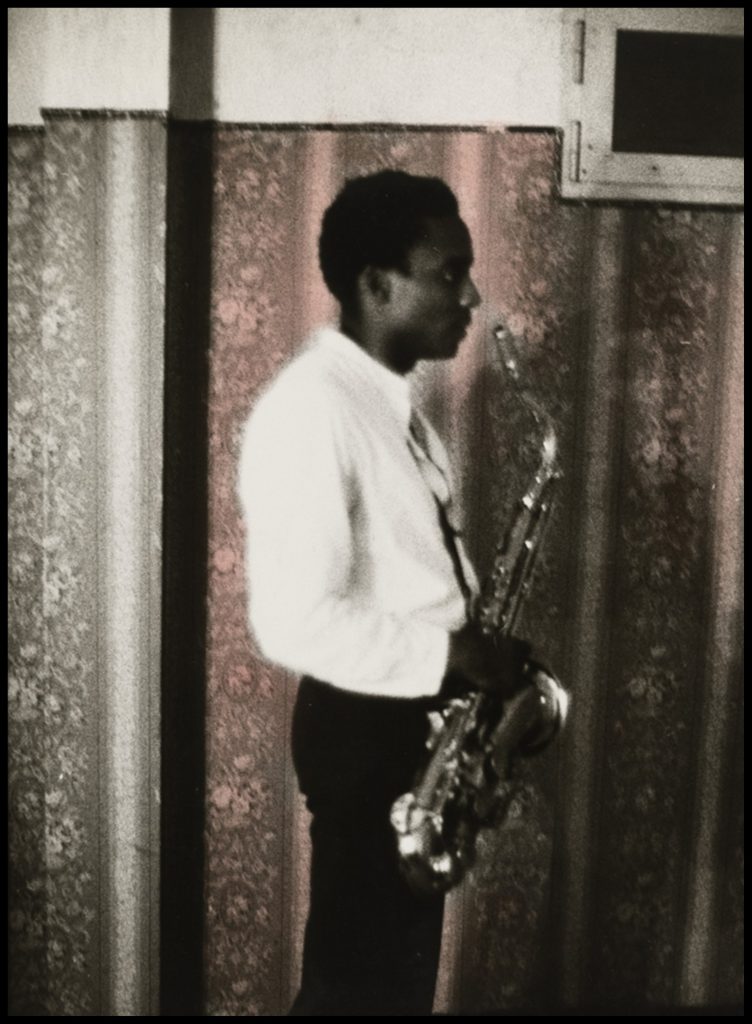

During the 1960s, film director Shirley Clarke captured Black residents of Harlem in The Cool World (1963). Clarke also captured — like John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959) — the New York City jazz scene in her film The Connection (1961). Smith tapped into this fading side of New York City when she started photographing jazz musicians, including legendary saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, who passed away in 2022.

“I photographed Pharoah Sanders, but it was at The Bottom Line,” said Smith. “They had rock people there. It wasn’t a jazz club like Sweet Basil or Village Vanguard.”

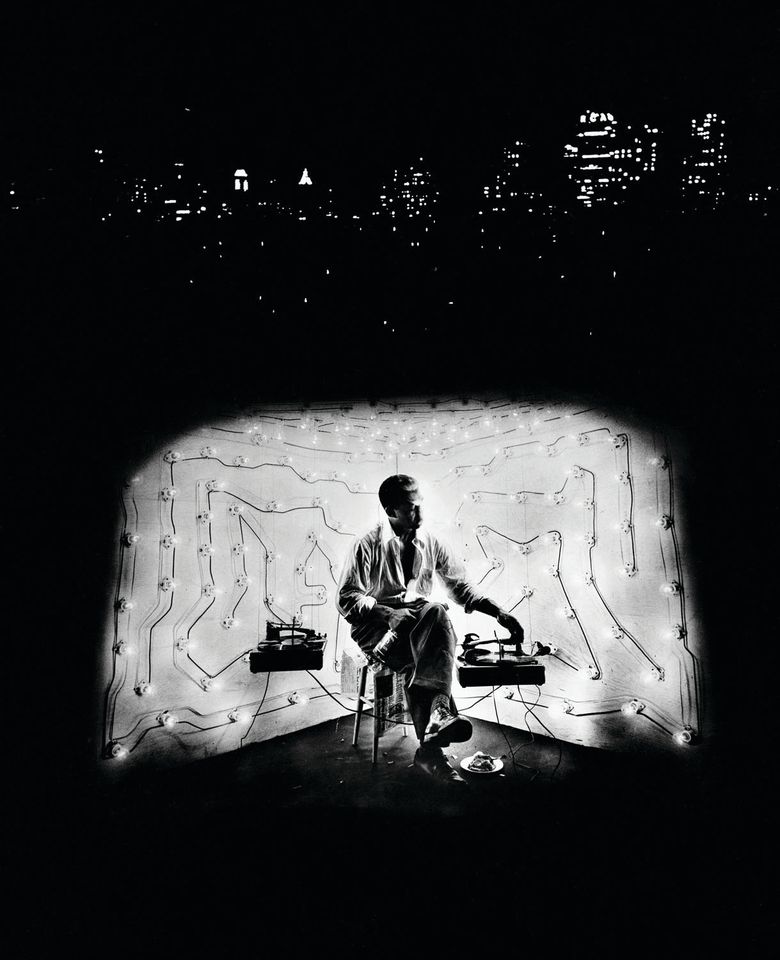

The CAMH exhibit deftly pays tribute to the musical side of Smith’s body of work: Two mystical Sun Ra photos and selections from the Red Hot Jazz series adorn the walls of the museum.

As for how she got into jazz photography? “I married a jazz musician,” she says with a laugh.

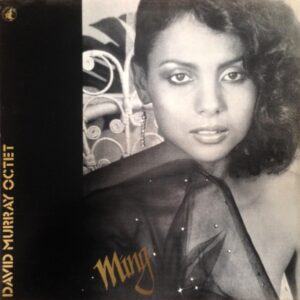

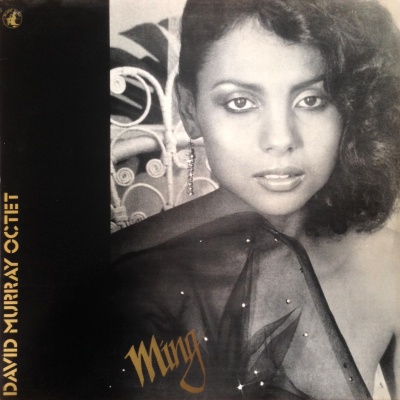

Smith’s former husband is tenor saxophonist David Murray, who once played with the Grateful Dead, as well as guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer and cornetist Olu Dara, the father of rapper Nas. Murray dedicated a 1980 album to Smith entitled Ming, but Smith says her favorite recording by her ex-husband is actually Ballads (1988). Smith is pictured on the covers of both albums.

Their son Mingus Murray — named after bassist Charles Mingus — is a composer who plays guitar, bass, piano and keyboards. He created all the music featured in the CAMH exhibit, including the ambient, ethereal meditation room soundtrack. Murray also collaborated with his mother on the Afrofuturistic short film Suspension (Hubris) (2023), which is part of the exhibition.

“It was pretty seamless,” Murray tells PaperCity. “The music just comes if I have a concept. It’s fun to collaborate with my mom. I understand her work completely, and she understands me. When we get together and work on something, there’s just a flow.

“It set a standard for me that is really, really high. My mom always says I’m a consummate artist, and that I need to keep on producing things and producing concepts. And even if it doesn’t fit into the mainstream way of doing music, I should always continue to work on my craft.”

Describing the meditation room music, Murray notes: “I didn’t want to have any distractions, so I wanted something to flow easily. It’s meditation — the idea is to be minimal and focus on breathing and release.

“That’s how I feel with my mom’s work. She encapsulates so many different ideas and spiritual modalities. It’s all there.”

One well-known aspect of Ming Smith’s story is her work with the New York City-based Kamoinge Workshop, an important collective of Black photographers.

As photographer Dawoud Bey, a longtime friend of various Kamoinge members, told this writer in 2022: “Kamoinge was a tangible, living example of the fact that there was such a thing as a Black photographer. As a young person interested in photography, their example and their existence gave me the reassurance that I could be this thing that I was thinking of becoming.”

Like Bey, Smith was greatly influenced by the genius of Kamoinge Workshop leaders Roy DeCarava and Louis Draper — the latter of whom invited Smith to join the collective.

“Kamoinge introduced me to photography as an art form — the quality of the prints and composition,” Smith says. “I’m pretty instinctual, so once I got it, I understood. I also did a lot of research and looked at other great photographers like Brassaï, Robert Frank and Bresson.

“But I would say I’m 97 percent a loner. Once I got it, I was on my own trip.”

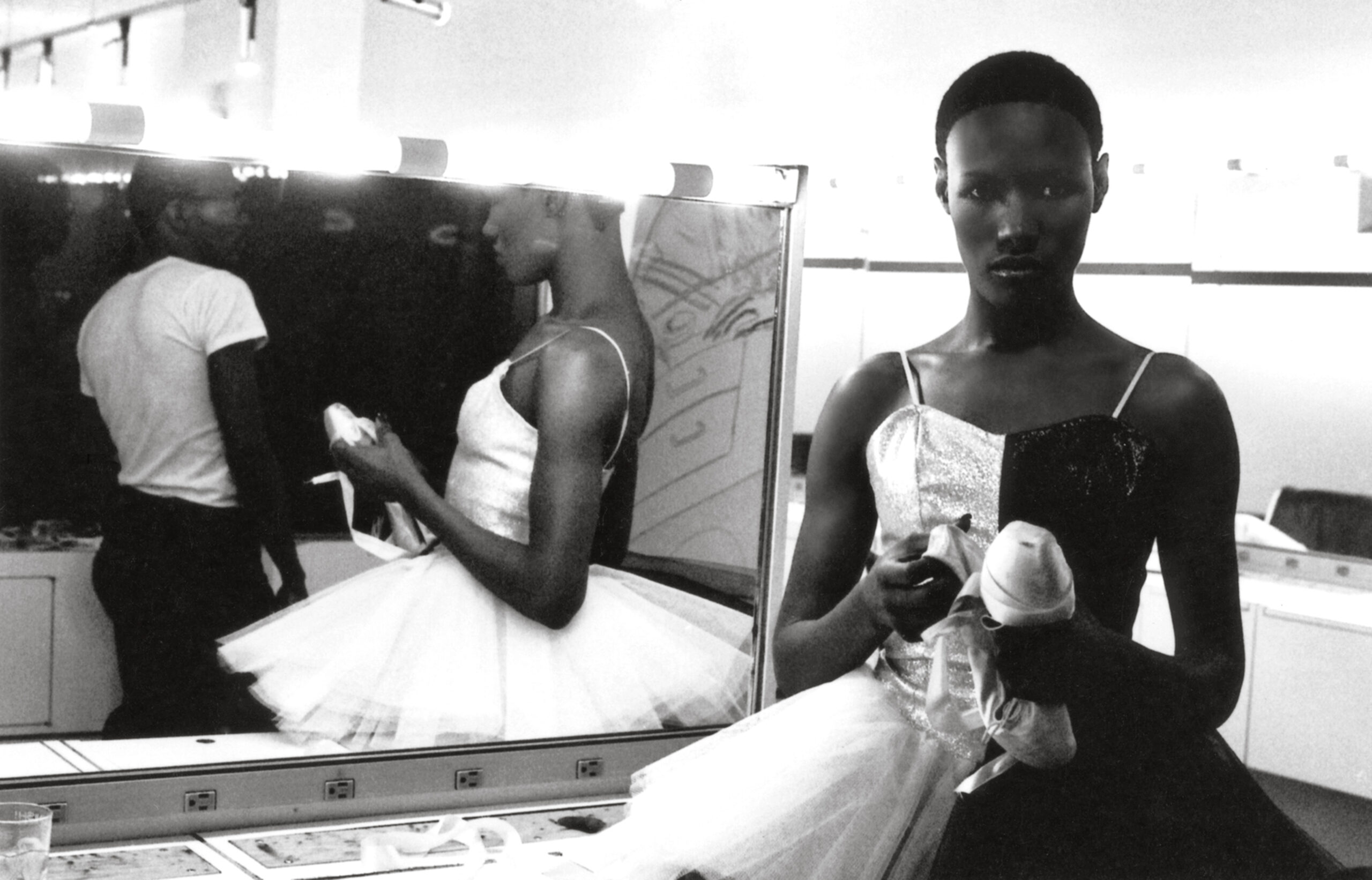

Iconic model and actress Grace Jones appeared in numerous Smith photos during the 1970s, taken at various long-gone New York landmarks: Andre Martheleur’s Cinandre hair salon and legendary nightclub Studio 54. In fact, Smith says it was Martheleur who gave Jones her iconic androgynous flat top haircut. The two young models shared a bond of friendship.

“I think the sense of truth and authenticity of an experience is one of the good parts of my work,” Smith says. “I think that’s why people like the Grace Jones photographs. That’s how she was at that age (during her twenties). She wasn’t the successful Grace Jones. She didn’t know what she was going to do. We both didn’t know.

“How are we going to survive this Earth? How are we going to survive in life? She didn’t have a lot of money. Even being a model was a new thing. We came as young Black women trying to navigate the world. We wanted to be someone.”

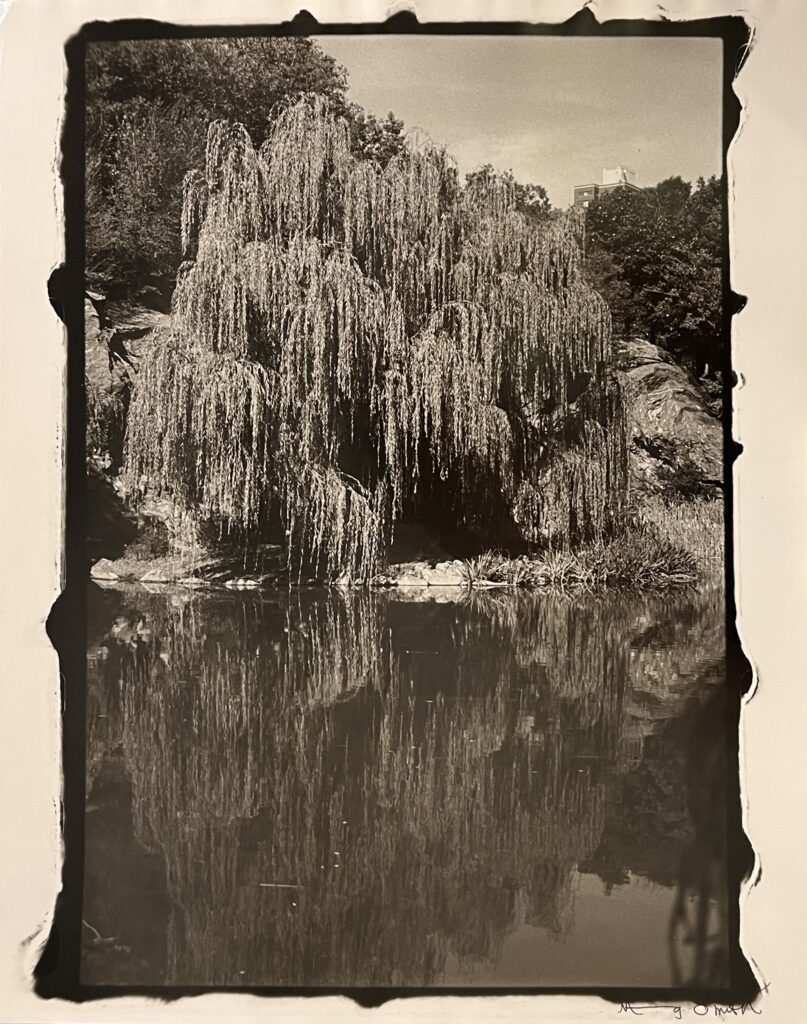

In addition to Jones, Smith has been inspired by Black women creatives such as Katherine Dunham, Zora Neale Hurston, Lorraine Hansberry and Octavia Butler. But she is also inspired by Harlem, where she currently lives, after a California phase in Laurel Canyon and Studio City.

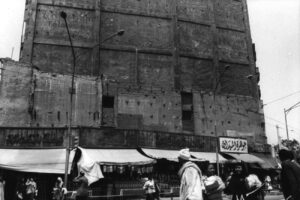

“You pass through Harlem. You see people, but you don’t really know them,” Smith says. “It’s more of a feeling. It’s fragmented. And it’s Black people. There’s an energy there. My work is not about this particular person, their face, their features.

“It’s about Black energy. It was Harlem, but centering more of the feeling of Harlem.”

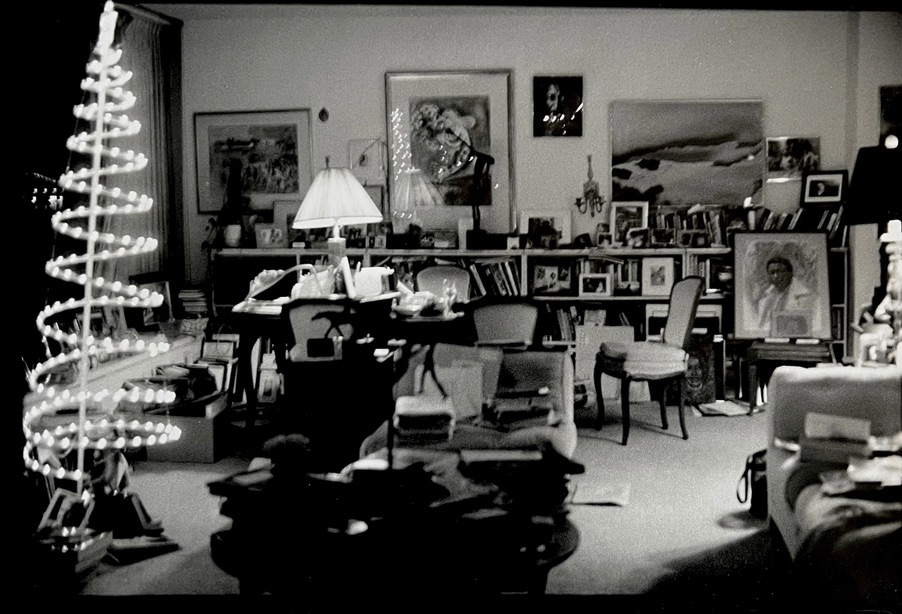

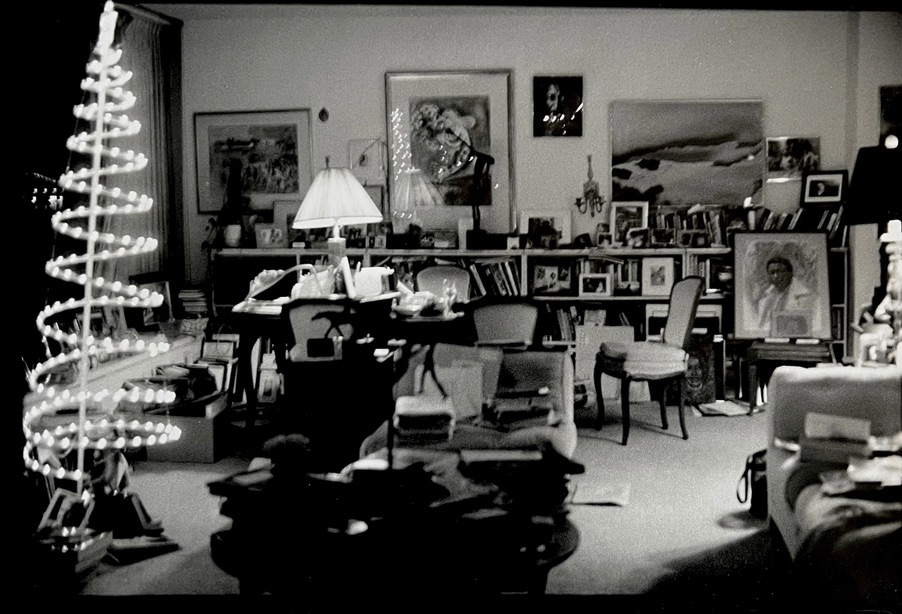

One of Smith’s all-time favorite photographs she has taken is Gordon Parks Last Christmas (2005), which was displayed at Houston’s Barbara Davis Gallery this past summer. It was Parks who wrote the foreword to the monograph A Ming Breakfast: Grits and Scrambled Moments (1992), and who gave Smith one of her first compliments as a photographer, when he told her “You have a really good eye.”

“I saw his photographs in Life magazine as child, but I didn’t even understand that this was Gordon Parks. . . he was a musician,” Smith says. “He was a Renaissance man.”

That good eye has made it easy for Ming Smith to capture so many unforgettable, breathtaking moments. At Art is Bond gallery, lead gallery assistant and artist Christopher Paul pulled out a hidden gem: a rarely seen archival silver gelatin print of Smith’s Duke Ellington photo entitled Ellington Continuum (ca. 1975-78), and an archival print of a photo Smith took of Tina Turner.

A relatively unknown fact about Smith? She was a dancer, along with Hairspray (1988) choreographer Ed Love, in Turner’s 1984 music video for “What’s Love Got to Do with It.”

“I brought my camera, and when I saw that image of Tina Turner, I captured that because she wasn’t ‘on,’” Smith says. “It was just a quiet moment between takes. And that’s how I captured the Tina Turner photograph.”

As for the guiding principle of her work, Smith notes: “I took photographs of people I loved or admired. They weren’t necessarily famous, but they were beautiful to me. They were highly committed to Black culture and authenticity.

“When I think about it, I guess most of my work really came out of love.”

“Ming Smith: Feeling the Future” begins its national tour at the International African American Museum (IAAM) in Charleston, South Carolina and will show there from January 31 to April 28, 2024. Learn more here. “Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility,” October 20, 2023 to April 7, 2024 at the Guggenheim Museum, will feature photographs from Ming Smith’s “Invisible Man” series. Learn more here.

_md.jpeg)