Pioneering Neon Artist Chryssa Gets Reintroduced to the World by an Enthralling Menil Exhibition — A True Pioneer Rises Out of Obscurity

Paving the Way For Many Greats and Creating Art Ahead of its Time

BY Ericka Schiche // 03.09.24Chryssa's "The Gates to Times Square," 1964-1966, at Buffalo AKG Art Museum. (© The Estate of Chryssa, National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation)

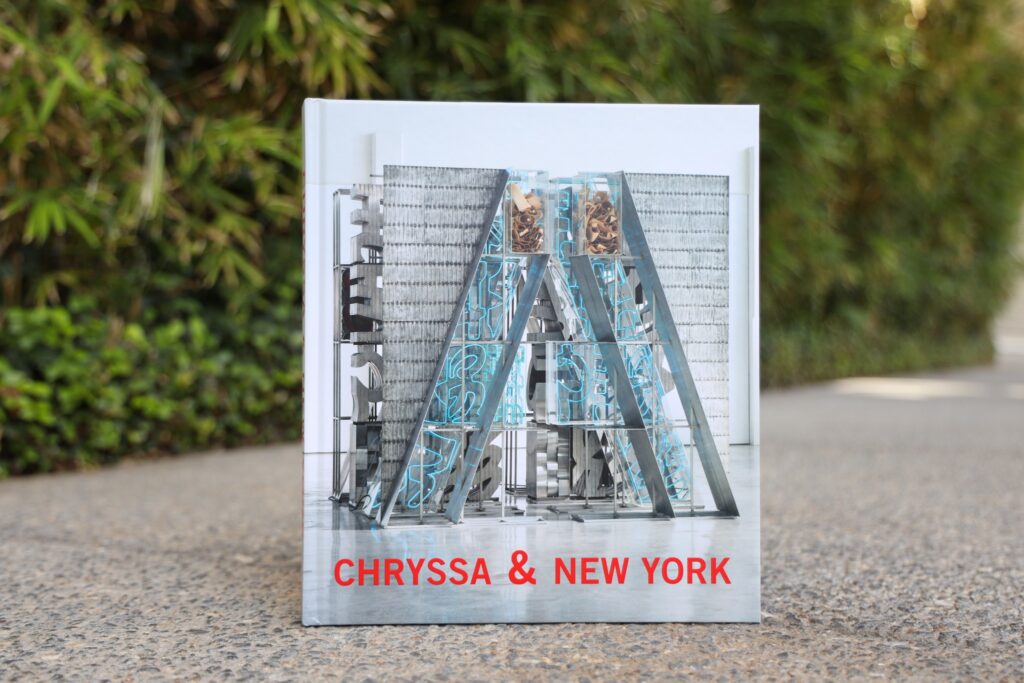

The Menil Collection’s “Chryssa & New York” exhibit has lifted neon art pioneer Chryssa Vardea-Mavromichali, known simply as Chryssa, out of obscurity. Showing through this Sunday, March 10, the comprehensive survey introduces viewers to the Greek-born artist’s various groundbreaking art making styles. Co-curated by The Menil’s senior curator Michelle White and Dia Art Foundation external curator Megan Holly Witko, the exhibition focuses on Chryssa’s works created in New York City during her most productive phase from the late 1950s to 1970s.

Before settling in the United States, Chryssa attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in the Montparnasse district of Paris. She joined an impressive list of art school alums, including Isamu Noguchi, Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, Alberto Giacometti and Serge Gainsbourg.

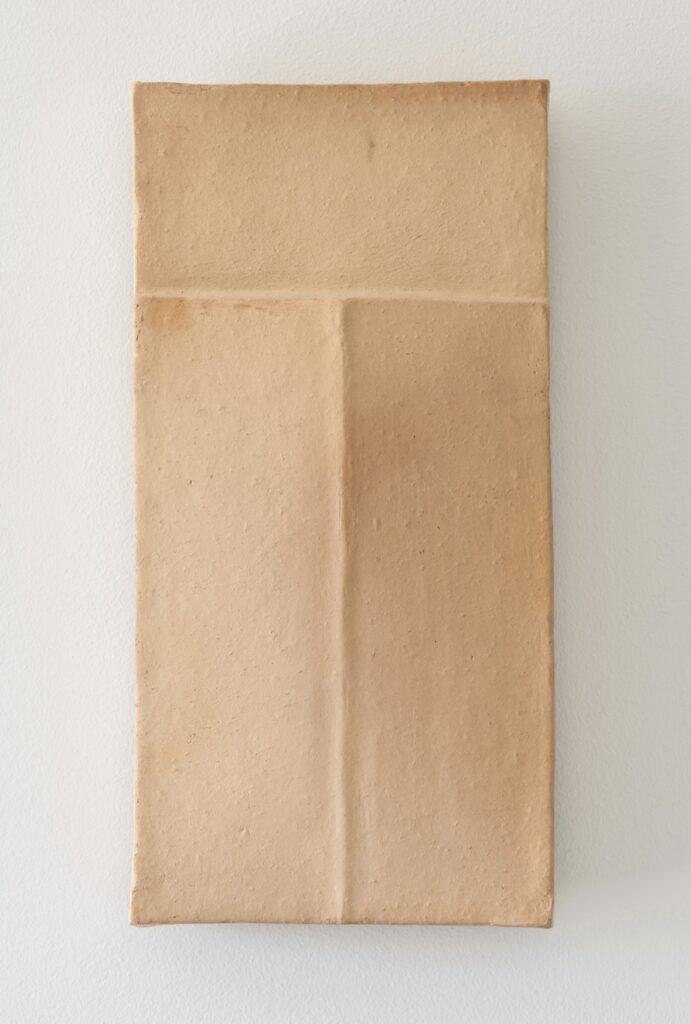

Like fellow Greek kinetic sculptor Takis, who created bronze Cycladic sculptures, Chryssa created reverential artworks inspired by a knowledge of Bronze Age Cycladic art and the Cyclades islands. Her Cycladic Books were made of plaster and, in some cases, terracotta. The neutral toned, monochrome proto-Minimalist books — positioned across from the entrance to the “Chryssa & New York” exhibit — are intriguingly mysterious.

Before Her Time

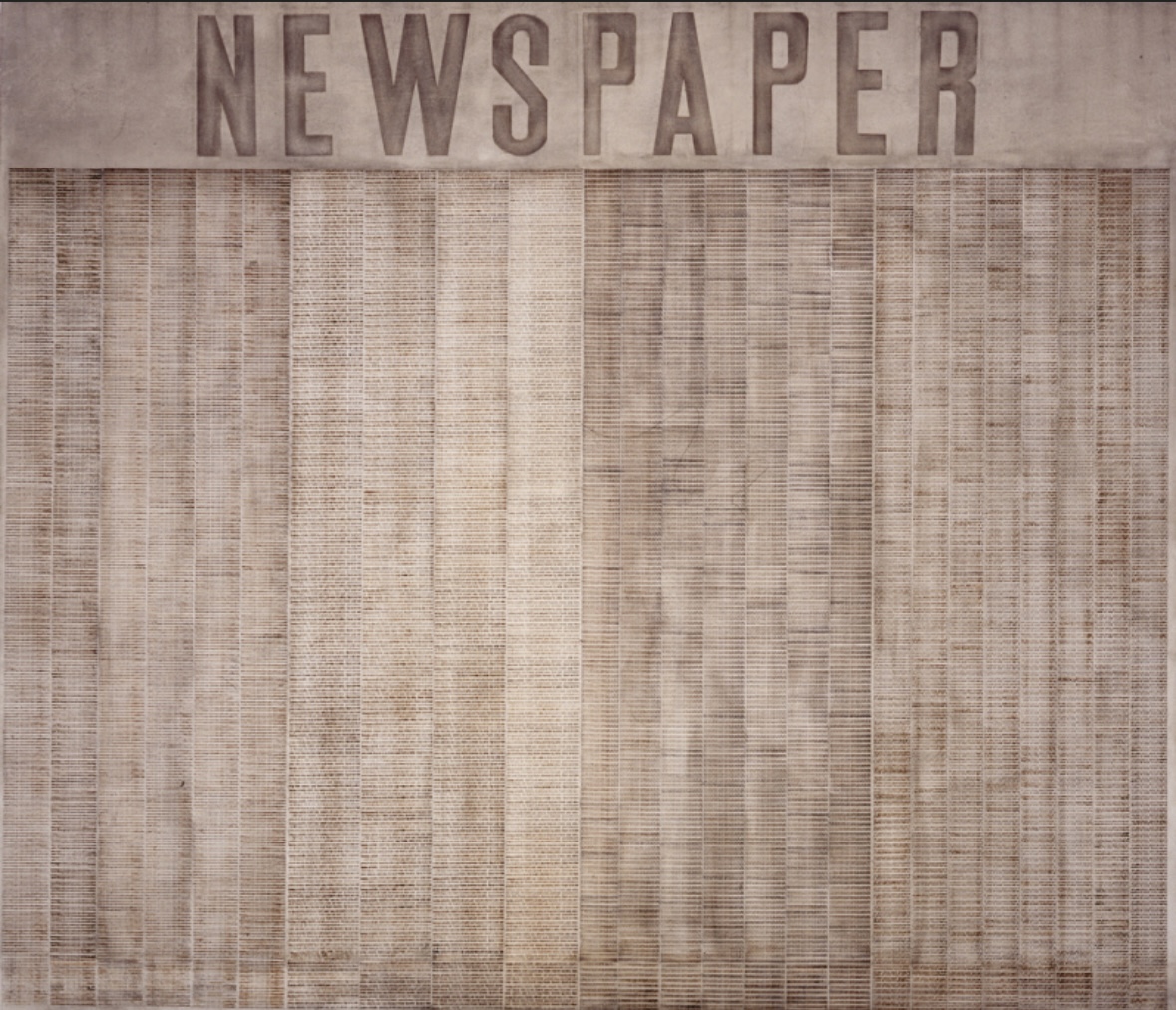

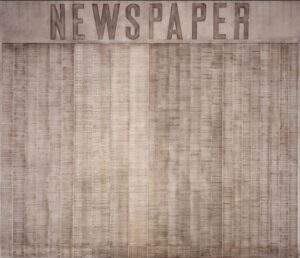

In addition to the Cycladic Books, Chryssa’s oeuvre includes many examples of art ahead of its time. Her newspaper-inspired artworks are reminiscent of Neo-Dadaism, and her alphabet-inspired artworks are comparable to the work of Jasper Johns. She made numerous sculptures which could be described as Proto-Minimalist — at least 17 years ahead of the Minimalist movement’s introduction.

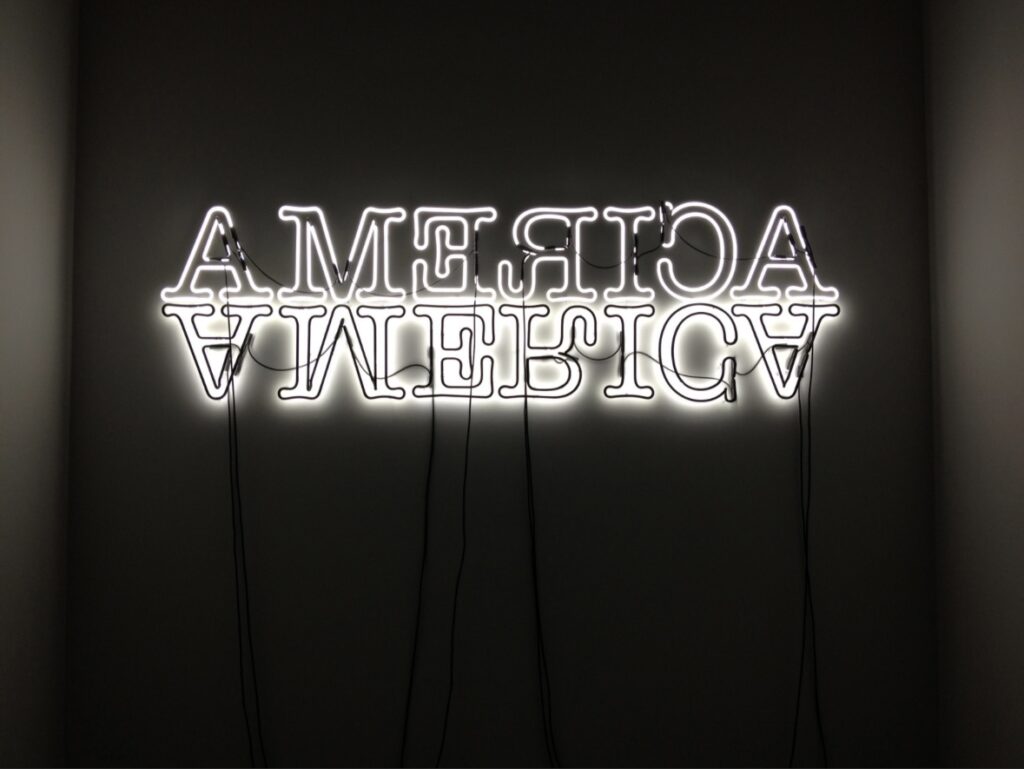

Chryssa’s unique ability to strip the alphabet and language of its meaning, question and recontextualize it is something few artists have mastered. As Michelle White notes in her catalogue essay on Chryssa, Ad Reinhardt “made a friendly remark that her metal casts and plaster tablets filled with letters did not spell anything.”

Regarding Chryssa’s pre-Pop Art work, art critic Blake Gopnik has expressed that Chryssa’s silkscreen prints with repetitive motifs came before Andy Warhol’s experimentation with printmaking. Gopnik’s discussion at Dia Chelsea, led by Megan Holly Witko, delves further into Chryssa’s innovativeness. The artist’s Car Tires (1959-62) and The Stock Market (1962) helped paved the way for Pop Art.

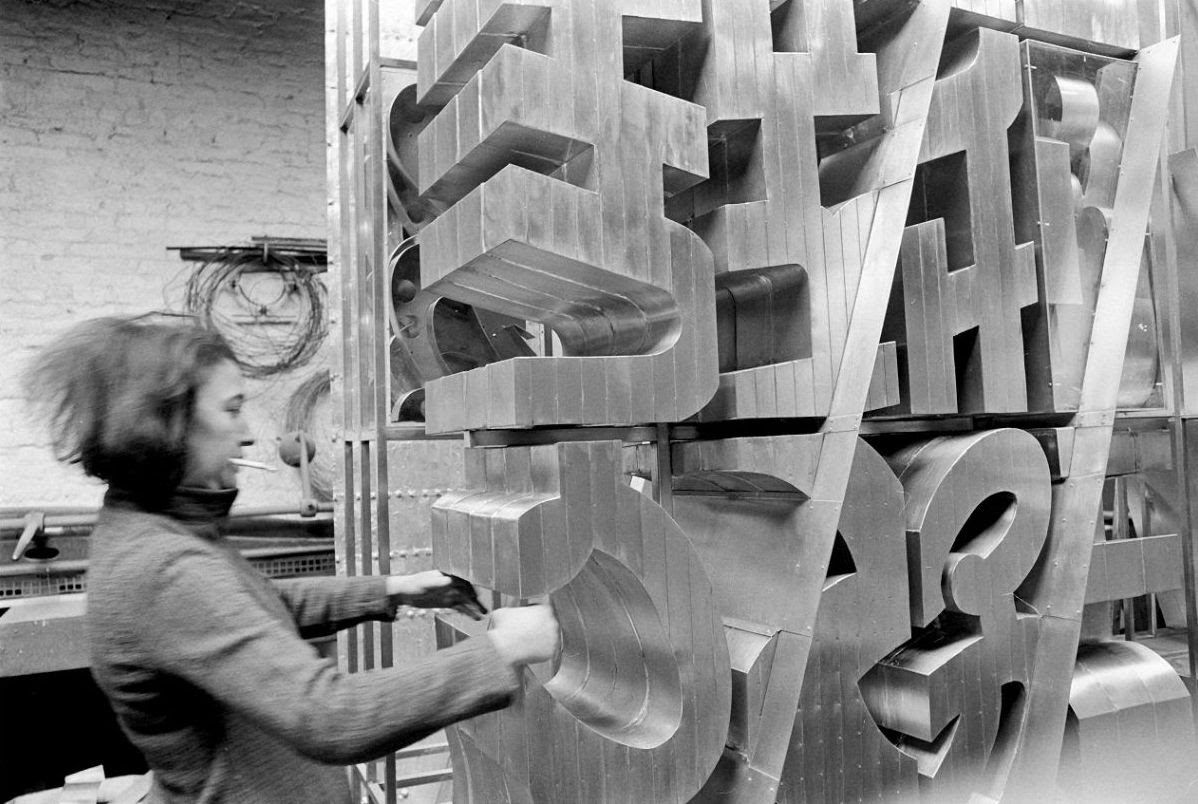

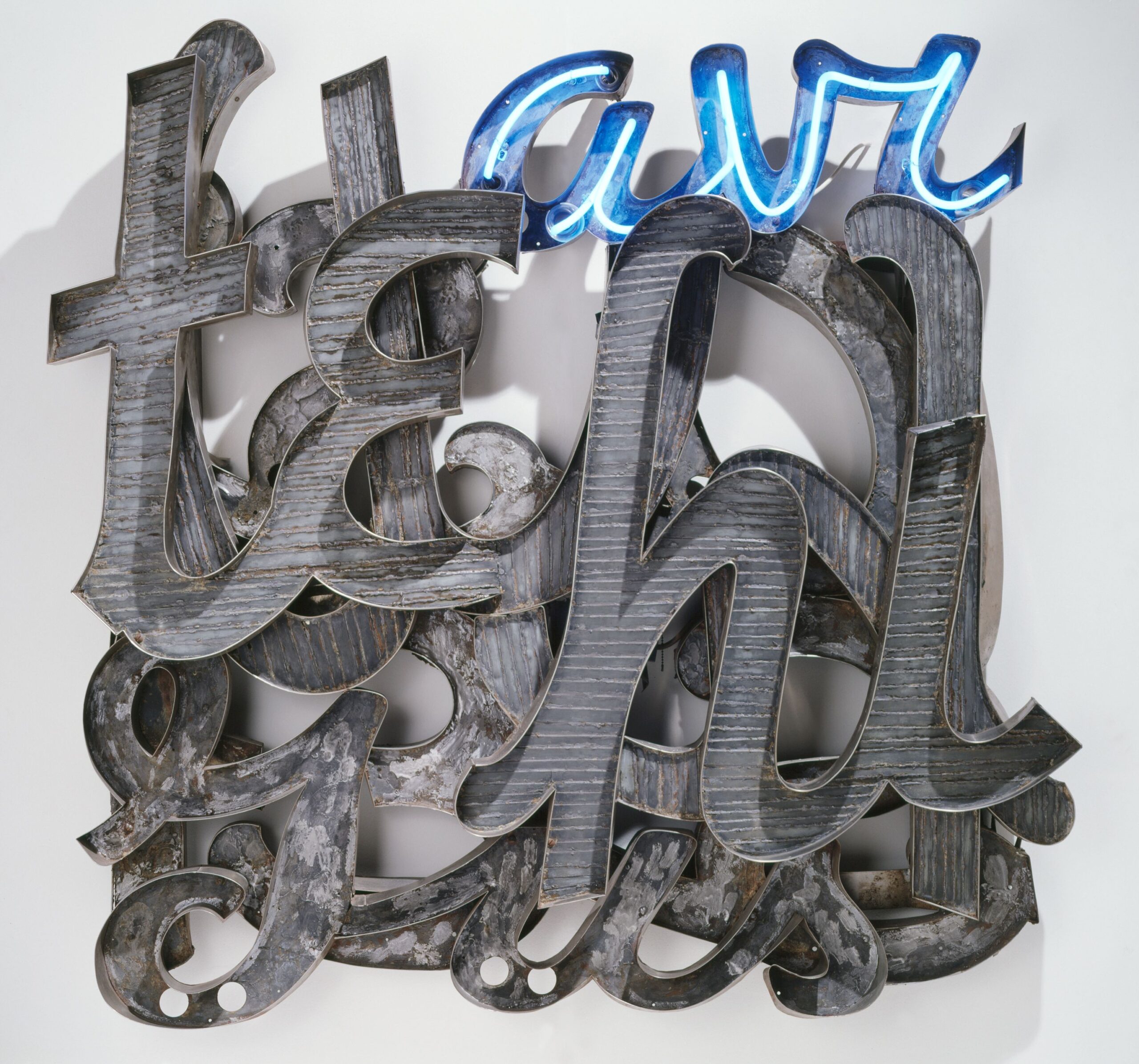

Although Chryssa forged ahead with avant-garde art making in various mediums, it is her neon artworks which unquestionably established her as one of the best in her field. Among her luminist sculptures, The Gates to Times Square (1964-66) stands alone as the pièce de résistance. Other sculptures including Times Square Sky (1962) to Five Variations on the Ampersand (1966) reveal an artist way ahead of her peers and the times.

Chryssa In a World of Neon

Culturally speaking, neon art has graced the changing cultural landscape for decades. Nelson Algren described a “fluorescent jungle” in his book of short stories titled The Neon Wilderness (1947). Photographer and filmmaker William Klein established his cinematic career with the neon light-dominated short film Broadway by Light (1958). Even the movie Blade Runner (1982), defined by its retro futuristic, noirish and dystopian milieu, is elevated by Tom Southwell’s neon art.

Chryssa understood the cultural impact of neon within pop culture on an international scale. She paved the way for artists such as James Turrell, Bruce Nauman, Glenn Ligon, Jenny Holzer and Tracey Emin. She was a pioneer of neon art and artist nonpareil. Through her neon artworks, Chryssa achieved a new spatiotemporal dimension uniting past, present and future.

Restoring Chryssa’s Work

Neon artist Tim Walker, owner of Houston’s The Neon Gallery along with his wife Suzette, helped restore Chryssa’s neon artworks for the “Chryssa & New York” exhibition.

Walker notes that the fabrication process of neon tubes has not changed since before Chryssa’s pieces were made. However, many neon sign components used in Chryssa’s era — the ’60s and ’70s — are now extremely difficult to find.

“Fortunately, we were able to locate discontinued components,” Walker tells PaperCity. “Transformers were custom made to original standards. It was a joy to work with Joy Bloser and the conservation team at The Menil.”

During a lecture delivered on January 10, 1968 at New York University, Chryssa discussed the independence of her neon sculptures from technology. Explaining her philosophies, she stated: “The transformers will eventually wear out. Fortunately, there is the sun and the moon, day and night. Without electricity, my sculpture will still survive.”

A Conservator’s Perspective

Joy Bloser, assistant objects conservator for The Menil Collection, appreciated the collaborative effort to restore Chryssa’s work.

“One of the highlights for me has been working with a broad network of conservators, neon benders and historians to bring Chryssa’s work back into public view,” Bloser says. “One aspect to Chryssa’s works that make conservation challenging is that she used unique operational components that are also included as sculptural elements in her neon works.

“For example, when a transformer burns out or the electronics need repair, they are also visible to the viewer and form part of the sculpture.”

Echoing Chryssa’s sentiments on timing, Bloser notes: “She played with timing sequences, leaving long stretches where the piece turns off, then flicks on briefly. Something she compared to breathing — whether in or out.

“Beyond the technology, the actual glass bending in her work is extraordinary. There are not many neon benders today who could bend her ampersands in perfect repetition or the 25mm black light blue glass into the bold forms she specified.”

Bloser sees Chryssa, who died in Athens in 2013, as someone who transcended limitations.

“Her work with fabricators, as well as the work in her own hand, all embody this iterative and adaptive process that dominate the limitations of the techniques employed,” she says. “As someone who looks a lot at how things are made, I think I appreciate that the most.”

The comprehensive “Chryssa & New York” survey is showing through this Sunday, March 10 at The Menil Collection. To learn more, go here. The exhibit will then travel to Wrightwood 659 in Chicago, with that running May 3 through July 27. A catalogue for the exhibition, which includes an essay by The Menil Collection’s senior curator Michelle White, is available here.

_md.jpeg)