Knights and Priceless Tapestries Come To Life In Houston —MFAH Shines a Light on the Battle of Pavia

Taking You Back Centuries to 1525 In a United States Museum First

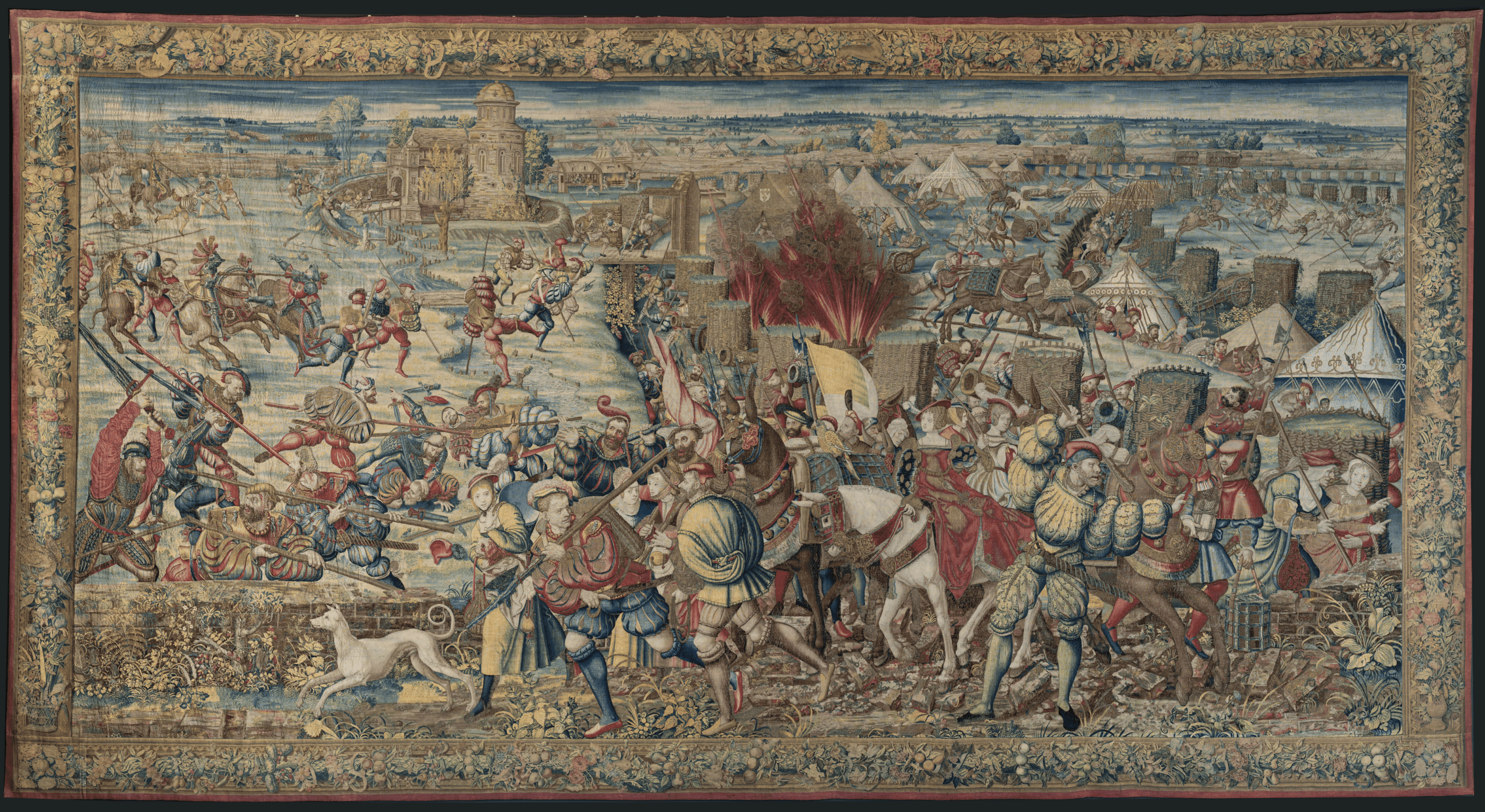

BY Adrienne Jones //"The Invasion of the French Camp and the Flight of the Ladies and Servants" (detail), circa 1528–1531, designed by Bernard van Orley, woven by Willem and Jan Dermoyen, at MFAH. (© Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte)

“The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne” – Geoffrey Chaucer

It’s hard to overstate the splendor and beauty that awaits at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s exhibition “Knights in Shining Armor – the Pavia Tapestries.”

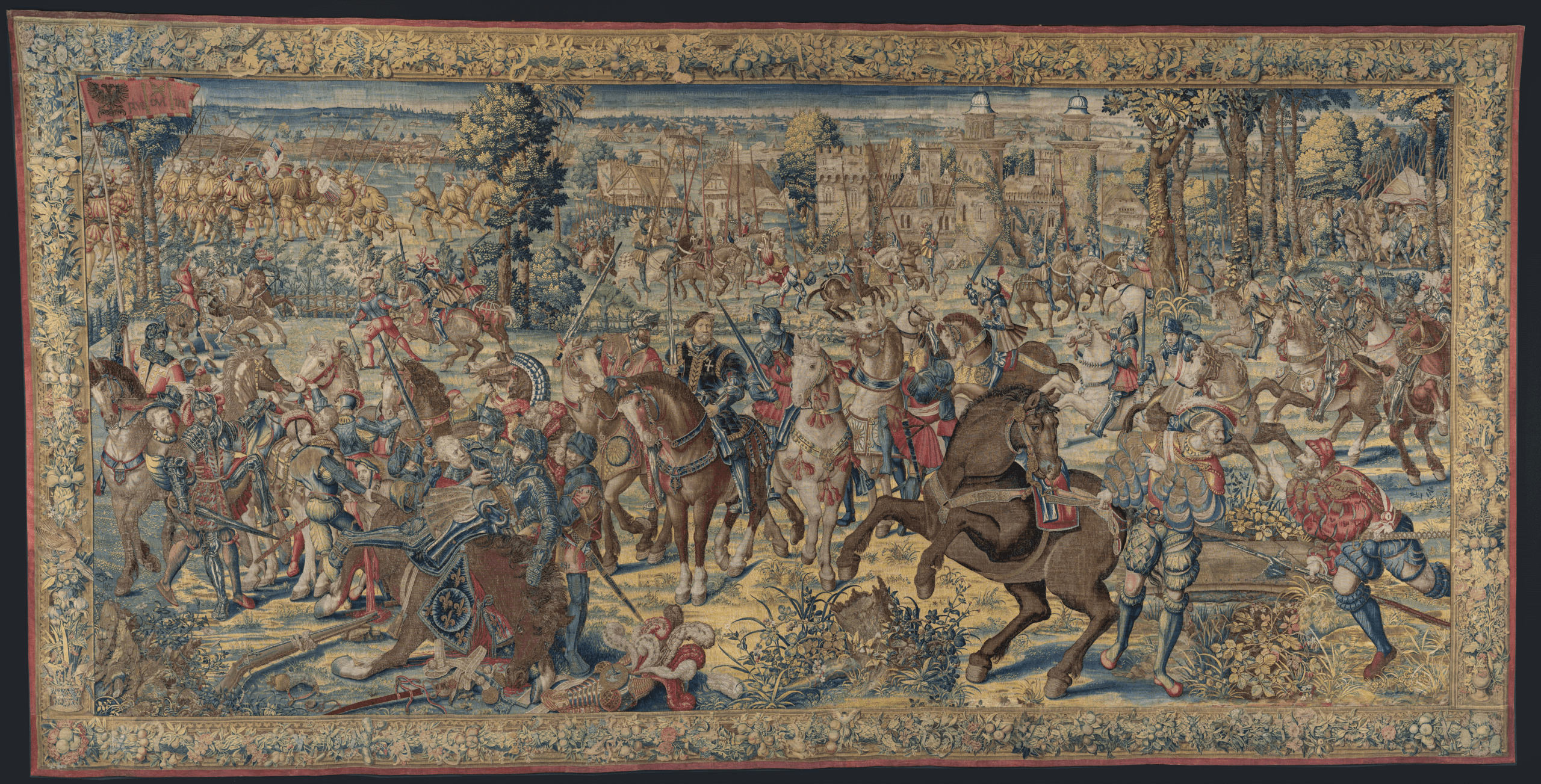

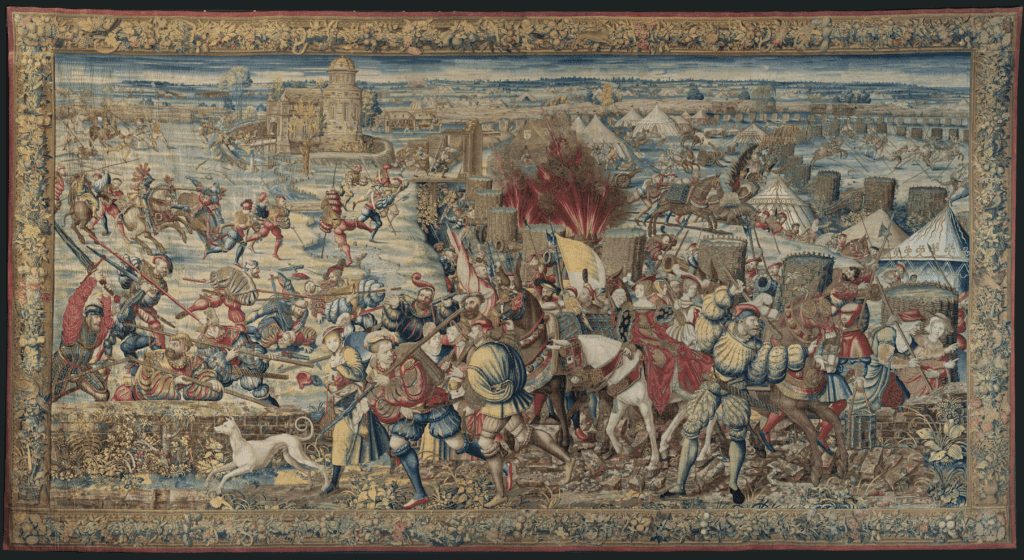

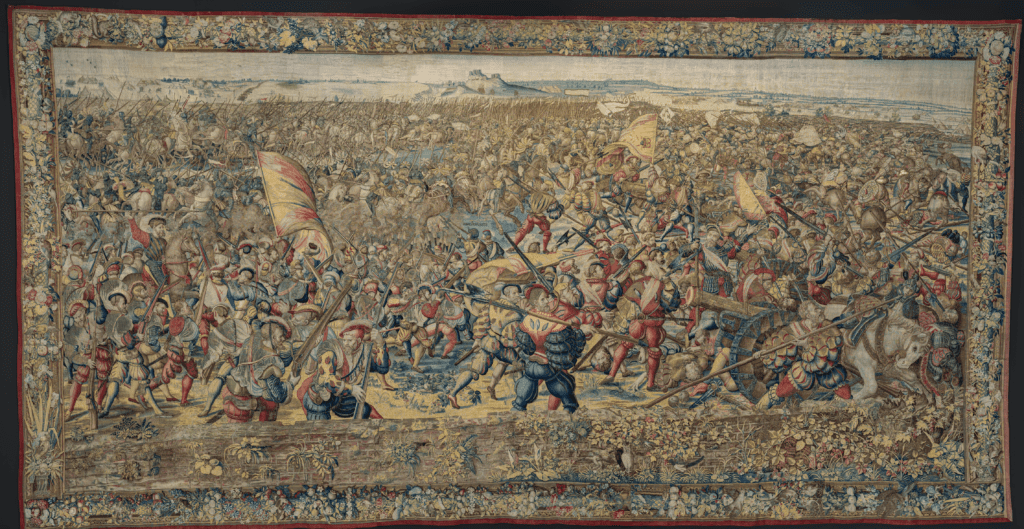

The priceless series of seven immense tapestries woven in Brussels depicts the 1525 Battle of Pavia, fought 20 miles South of Milan between the victorious Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France. These tapestries are together for the first time in the United States, on loan from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples.

Perhaps entering MFAH’s enormous exhibition space should come with a warning. The experience is simply breathtaking. Suddenly one is encircled by scenes of desperate all-out warfare, woven in still-vibrant hues of the finest wool, silk, gold and silver thread. In their immersive sweep, massive floor-to-ceiling scale and immediately evident beauty, the tapestries are one of the most magnificent creative and technical achievements in the history of Western art.

The Battle of Pavia’s World-Changing Impact

The monumental work portrays a consequentially important military event that that changed the geopolitical landscape of Europe for centuries. It was the decisive battle in the Italian War that had begun in 1521 between the Kingdom of France and the Habsburg Emperor — both sides with hereditary claims to the Duchy of Milan. Francis saw it as his destiny to conquer northern Italy, an endeavor in which his predecessor Louis XIII had failed.

French forces launched the attack in the early morning of February 24, 1525. The brutal battle, fought in the vast Visconti Park of Mirabello outside the city wall, lasted less than four hours. In the end, the French army was virtually demolished, including the aristocratic French cavalry in their armor. They proved no match for Charles’ Imperial troops, many armed with armor-piercing arquebuses, an early form of musket. French forces had no firearms. Francis’s personal undoing was leading his armored cavalry against gunpowder in a medieval-style charge with lances.

Francis was captured in battle when his horse was shot, and he was taken to Spain for a year. He gained his freedom by signing the Treaty of Madrid and ceding his lands in Italy and as far north as Flanders, Artois and Tournai, now in modern-day Belgium. Loss of life is estimated at 8,000 for the French, and 1,000 for the Hapsburg. Armies numbered more than 20,000 men on each side.

As MFAH assistant curator James Anno points out, the move to mechanized warfare and the centuries-long geopolitical effect of the Treaty of Madrid are among the reasons many historians cite Pavia as one of history’s most significant battles.

As for Francis I retaining France and the Holy Roman Empire taking over most of Italy, MFAH senior docent Gretchen Sassone notes: “The arms race starts here.”

A Sistine Chapel Connection

For centuries, tapestries had been the primary decorative form in the royal courts of Europe, designed by leading artists and hand-woven on looms. No expense was spared in using the finest of opulent materials. However, until Raphael’s designs for the Sistine Chapel tapestries — commissioned in 1514 by Pope Leo X, woven in Brussels and delivered in 1520 — tapestry design and texture appeared somewhat flat.

Raphael, one of the grand masters of Renaissance painting, was able to achieve shading, depth and a sense of volume in his tapestries by using perspectival lines and rounded figures who appeared to be in motion. His work marked a turning point in the art of tapestry and influenced Bernard van Orley, court artist to the Hapsburg rulers.

In 1500, Brussels was the bustling center of tapestry production of the Northern European kingdoms, which included France, England, the Holy Roman Empire and the Low Countries (present-day Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg).

The Pavia tapestries appear to have been commissioned shortly after the battle. Designed in Brussels by van Orley and executed between 1528 to 1531 in a workshop of Willem and Jan Dermoyen, they were presented to the emperor in 1531 when he returned to Brussels for the first time in nine years.

Each tapestry required five or six highly skilled guild craftsmen who worked from “cartoons” — full-scale designs that weavers could copy, cut in strips, and place under the warped threads. The head of a sweet-looking pet dog belonging to one of the ladies who was likely following her knight is all that remains of the original cartoons. However, van Orley’s seven preparatory drawings remain and are housed at The Louvre.

Many art historians note the apparent influence of Raphael’s work, which van Orley would have had the opportunity to see when the Vatican cartoons were woven in Brussels beginning in 1516. The Getty Museum notes in its own documents that “van Orley was called The Raphael of the Netherlands for his interpretation of Italian Renaissance ideas and forms.”

Thomas Campbell, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco, draws viewers’ attention to van Orley’s use of a foreground, middle ground and background, or what he calls the principal scene, then the secondary and tertiary. Though this was common in Italian Renaissance canvas composition, as Campbell points out, “No one had conceived of a tapestry like this in northern Europe.”

And yet, because of the artistry and fidelity to the particular colors, landscape, architecture, the very light of Pavia, and the artistic vision of van Orley, there is no way an observer would mistake the tapestries as Italian.

Interesting too is the extraordinary realism in the execution of individual faces and attire.

“Each of them – it’s a portrait,” Sylvain Bellenger, director emeritus of the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, notes. “They were famous enough to need to be represented with a very careful likeness. Some are named with transcriptions woven into the tapestry.

“Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor (who was not at the battle) is not represented, but his generals are clearly defined.”

The generals include the leader of the Imperial army and Viceroy of Naples, Charles de Lannoy and Charles, Duke of Bourbon.

Interestingly, the Lannoy family is still prominent in Luxembourg and Belgium. The current Crown Princess of Luxembourg was born Countess Stéphanie de Lannoy, the youngest of eight children of the Count of Lannoy, a Belgian noble and descendent of Charles V.

An MFAH Touch

The MFAH has done a superb job presenting the tapestries, which were last restored in 2023 by gently cleaning them and delicately replacing stitches (there are 24 warp threads per inch).

“Although they have lost 20 to 30 percent of their original intensity, they are still in remarkable condition and retain the full spectrum of their color, even if the silk especially is somewhat faded,” Campbell says.

To preserve the colors, the Houston museun has carefully orchestrated a kind of light show, rotating bright illumination among the seven pieces. It allows visitors to experience the brilliance of the original work. The effect is spellbinding.

“Knights in Shining Armor: The Pavia Tapestries” runs through Monday, May 26 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in the Caroline Wiess Law Building. For information and schedule of weekly afternoon drop-in tours and lectures, go here.

_md.png)

_md.jpeg)

_md.jpeg)