Groundbreaking Dallas Artist Turns Eggs Into Magical Paintings: Ancient Technique Needs to be Seen to be Believed

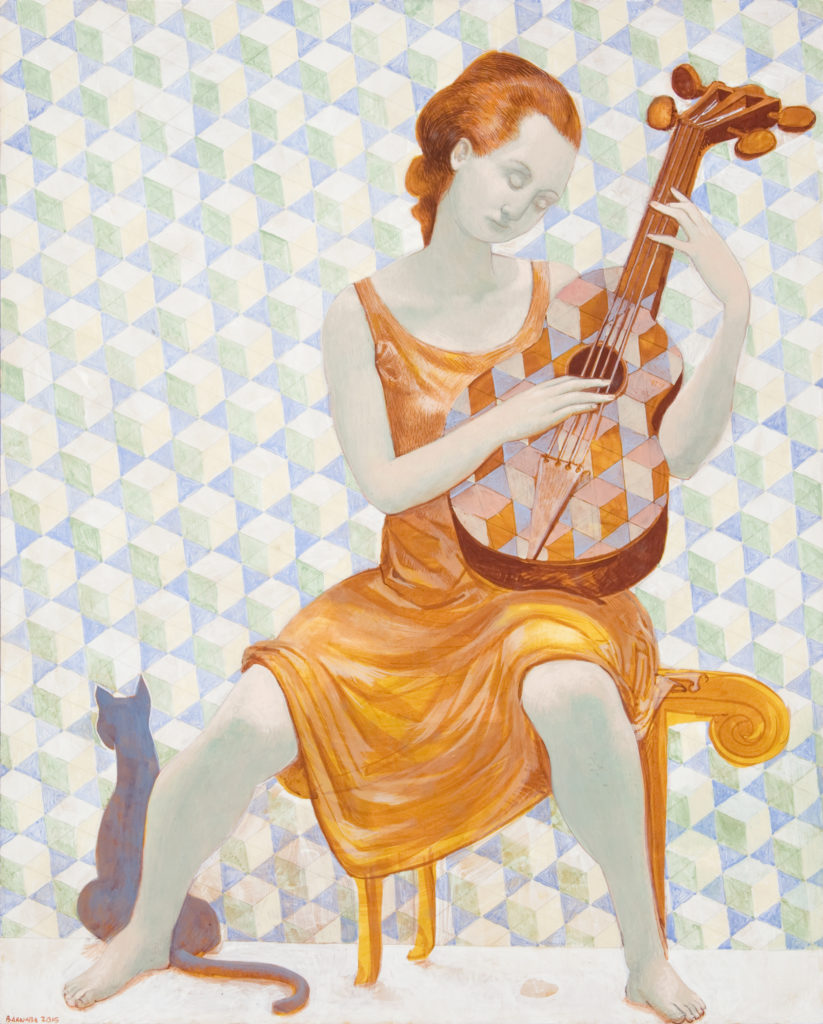

BY Rebecca Sherman // 05.25.17Barnaby Fitzgerald's "Columbina," egg tempera, graphite, and silverpoint on birch panel, 2015

Dallas artist Barnaby Fitzgerald creates many of his works in egg tempera on panel, an ancient painting technique that, as the name implies, incorporates egg yolk with colored pigments. He estimates he goes through about 40 eggs a year to produce his paintings; one egg lasts about three days and covers 10 square feet of canvas.

He’s explaining egg tempera to me over cups of espresso in the tidy kitchen of his charming 1926 house in old East Dallas, where the floors slant a little, and a repairman has been steadily working to get his high-tech new dishwasher running properly. The problem, Fitzgerald surmises, is not in the dishwasher’s mechanics, but in his own failure to read the detailed operating instructions that came with it.

“Who reads instruction manuals?” Fitzgerald quizzes rhetorically in a light brogue, acquired from a childhood in Italy and prep schools in Ireland. “Instructions are like Baroque poetry,” he says, his eyes dancing, and his voice laughing. “It’s something we all know is out there, and we know we’re supposed to read it, but we don’t.”

The same might be asked when attempting to understand the meaning behind an artist’s work — we know it’s there, but do we need a manual to appreciate it?

Fitzgerald’s own exquisite works, rife with literary symbolism and historic allegory, are easy enough to enjoy by just looking at them. His large oil paintings on linen and his smaller egg tempera panels are awash in creamy whites and golds, glowing with light and vivid color. There’s a mysterious, otherworldly quality to them, like an enigmatic dream we awaken from, wishing we knew what it meant.

Three days earlier, a show of his work opened at Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden, with a party for the artist. He wore a suit, and spent a lot of time surrounded by people asking him questions. Already, he was itching to get back in the studio to paint, he said.

Converted from an old garage out back, his studio is now a voluminous space with vaulted ceilings, drenched in natural light. An easel holds a small painting of a conch shell, and there are several paint-splattered tables meticulously organized with pigments, brushes, and books. Lately, he’s been obsessed with painting shells, he tells me, and that is because he’s also obsessed with skin; the flesh and folds of both are similar.

At one point during my visit to the studio, his wife, Sylvie Fitzgerald, stops by from her job as a director of a school, to check on the progress of the dishwasher. Statuesque with a lilting accent from her native African country, Togo, she is often his muse, he says, sometimes sitting as a model for his paintings.

Her influence in his art is also revealed in other ways, including his depictions of baobab trees, some of which he paints in egg tempera, or using the earthen pigments that are traditional to Africa. He imbues many of his paintings with brilliant, golden light, the kind that drenches the landscape in Togo.

He laments that people find his paintings that use rustic African pigments “too gritty,” but given time, maybe we’ll come around. It’s taken centuries for egg tempera to be resurrected from the ashes of the artist’s palette, after all.

Egg tempera is one of the oldest and longest-lasting methods of painting ever known — archeologists have even discovered it on Egyptian sarcophagi. It was the main paint medium used in classical Europe for centuries, until it fell out of fashion in the 1500s with the advent of oil paint.

Bringing a Lost Art Back to Life

By the time 18-year-old Fitzgerald began to pursue his degree in printmaking at the Instituto Statale D’Arte in Urbino, Italy, in the early 1970s, egg tempera was a lost art. “No one knew how to do it anymore,” he says. “Modernism had broken the chain.”

Ironically, Fitzgerald discovered that chain’s missing link in America, where he studied egg tempera for the first time at Boston University, and then later at Yale University, while pursuing a Master’s in painting. In 1984, he became a professor of art at Southern Methodist University and has since taught generations of students the age-old technique.

Fitzgerald’s paintings are clearly influenced by his European upbringing and an education steeped in great literature. Beautiful architecture and art enveloped him in Perugia where he spent his childhood; his father had been a poet, and his mother an artist.

“There were panel paintings and frescoes all over the place,” Fitzgerald says. “It was a totally visual experience.”

As a 20-year-old art student in Urbino, his classes were held inside a 15th-century palace designed by the great architect Luciano Laurana for a duke, and just next door was a national museum filled with egg tempera masterpieces, such as Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ. Fitzerald lived on the same street as Raphael, the legendary 16th-century painter of Madonnas.

“I was surrounded by some of the most exquisite, powerful works from the early Romanesque to the early Renaissance, my favorite periods,” he says. “But in the painting classes, all they were talking about was Andy Warhol.”

At school in America, pop art, abstract expressionism, and minimalism were all the rage. Abby Hoffman was screaming into a microphone in the Boston Commons, and the Black Panthers and the Vietnam War blared across headlines.

On one hand, Fitzgerald admired the artistic and cultural revolution his fellow students and teachers had embraced. On the other hand, he yearned to master the classic techniques of painting he’d grown up with. But instead of icons, he found iconoclasts.

“Artists were filling up buckets of color and throwing them on the walls,” Fitzgerald says. “There was a lot of drugs, a lot of drunkenness, and sex. I was 20, so, of course, that appealed to me, but I also had a deep desire to learn. Everybody was sort of copping an attitude, and there wasn’t a lot of substance behind it.”

Barnaby Fitzgerald found refuge in egg tempera classes taught at Boston University and Yale. There, his professors allowed him to use a live model, when everyone else was into painting abstractions. He mastered the use of color, which had always terrified him, and learned to layer his paintings with substantive meaning.

Symbolic Gestures

Caesura, one of Fitzgerald’s largest works at 90 x 72 inches, depicts a flame-haired woman looking up into the sky, while a massive, classical stone head — or hero, as he puts it — has cracked open in front of her. She and the head are resting on a narrow strip of land, which is supported by sticks.

“Caesura is about those moments in history when a loaded pause, an interruption, accentuates reality and its rickety architecture,” says Fitzgerald, who experienced his first “loaded pause” at age 10 in Italy, when news of JFK’s assassination spread. “The Italians all broke down in tears, on the streets, at school,” he says.

Everyone looked straight up, in a gesture which is the rhetorical way of saying, ‘We need help.’ The promontory on which the young hero’s head is broken is held up by a fragile beam, such as the ones used to hold up condemned houses after earthquakes.” He adds that a caesura is also a poetical term for the pause inside the line of verse.

Fitzgerald’s paintings often include oversized, symbolic references to his craft, such as a painter’s easel, or a sculptor’s caliper. Women, naked or draped in classical garb, figure prominently.

Through the Picture Plane depicts an artist working on a portrait of a woman he cannot see — the very surface he uses to paint her also blocks his view. The artist is rendered as a rough sketch, while she looms large, fully finished, residing in a world more complete than his.

So, whether or not you understand the meaning behind Fitzgerald’s transcendent works shouldn’t stop you from seeing his stunning show, or appreciating the high quality of his efforts. He’s a master painter who wields a brush with total confidence, and uses scale, color, and light to great effect.

They are more beautiful in person than could ever be translated in photographs. Also, we owe him a debt of gratitude for introducing egg tempera to generations of young artists in his classes, ensuring that this ancient medium lives on.

Barnaby Fitzgerald, “Concordances,” through Saturday, June 10, at Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden, 6616 Spring Valley Road, 972.239.2441.

_md.jpeg)