Dario Robleto's "American Seabed" (2014), on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, incorporates unconventional materials like fossilized whale ear bones and butterflies. The butterfly antennae are crafted from stretched audiotape recordings of Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row.” (Photo courtesy of Dario Robleto)

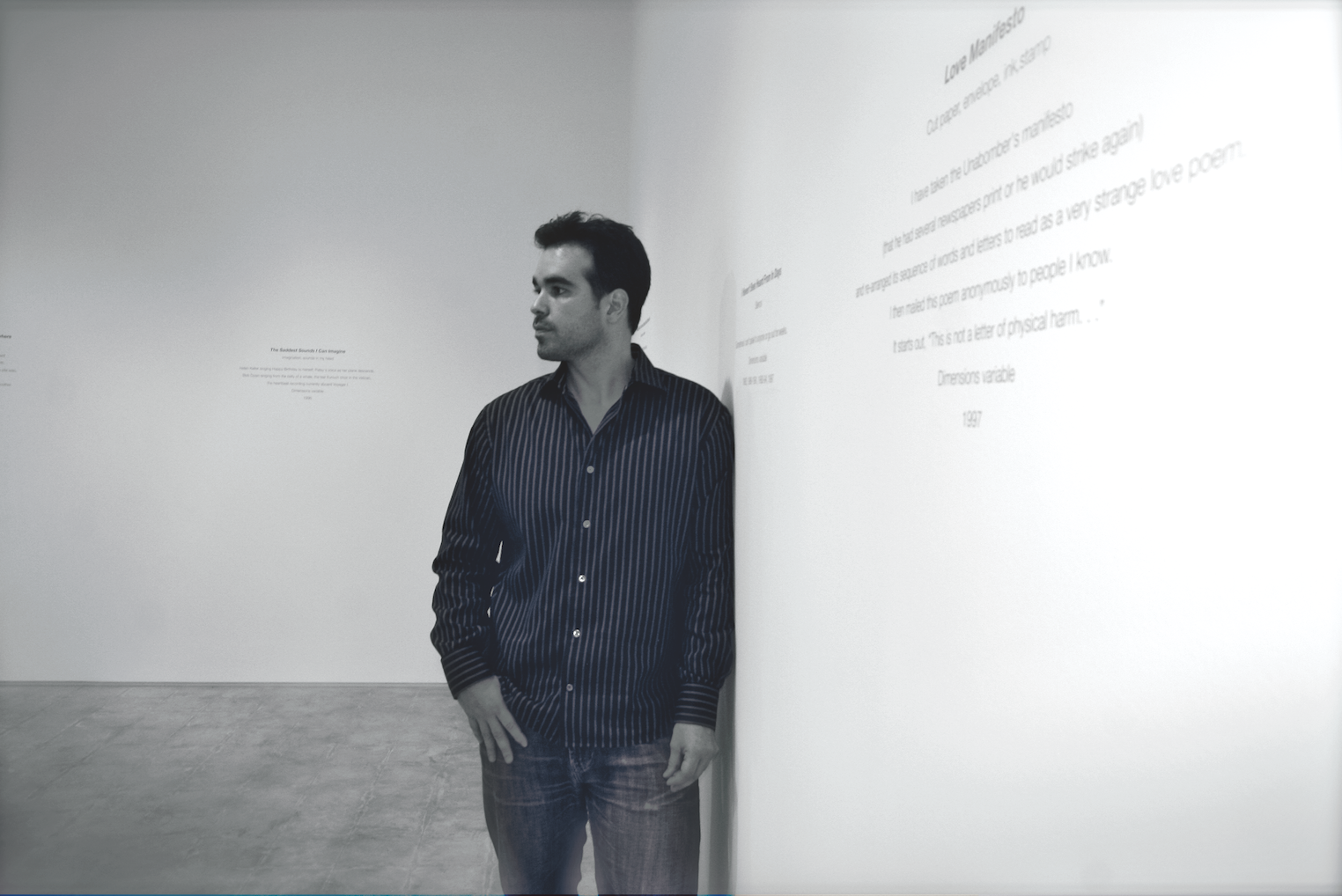

From crafting brass plates of early recorded heartbeats to stretching audio tapes into sculptures, Dario Robleto has his art down to a science. The quiet ease and humility with which the Texas-based Robleto approaches life and talks about his work belies his successes.

Robleto has exhibited internationally since the late 1990s, including at the Whitney Biennial (2004) and The Menil Collection in Houston (2014). Now he is the first artist to have a film commissioned by the National Gallery of Art as part of an exhibition on insect and animal consciousness.

Robleto’s newest exhibition also maintains an understated approach. The Signal at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth feels like a walk through a fantastical dreamscape.

Upon entering, floating butterflies mounted on black, bone-like objects within a large vitrine immediately catch the eye. Robleto’s sculpture, American Seabed, crafted from prehistoric whale ear bones, butterflies and stretched audiotape recordings of Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row” is a dynamic work. Combining elements of naturalist display, mixed media sculpture and Proustian recollection, it exemplifies Robleto’s unabashedly transdisciplinary practice.

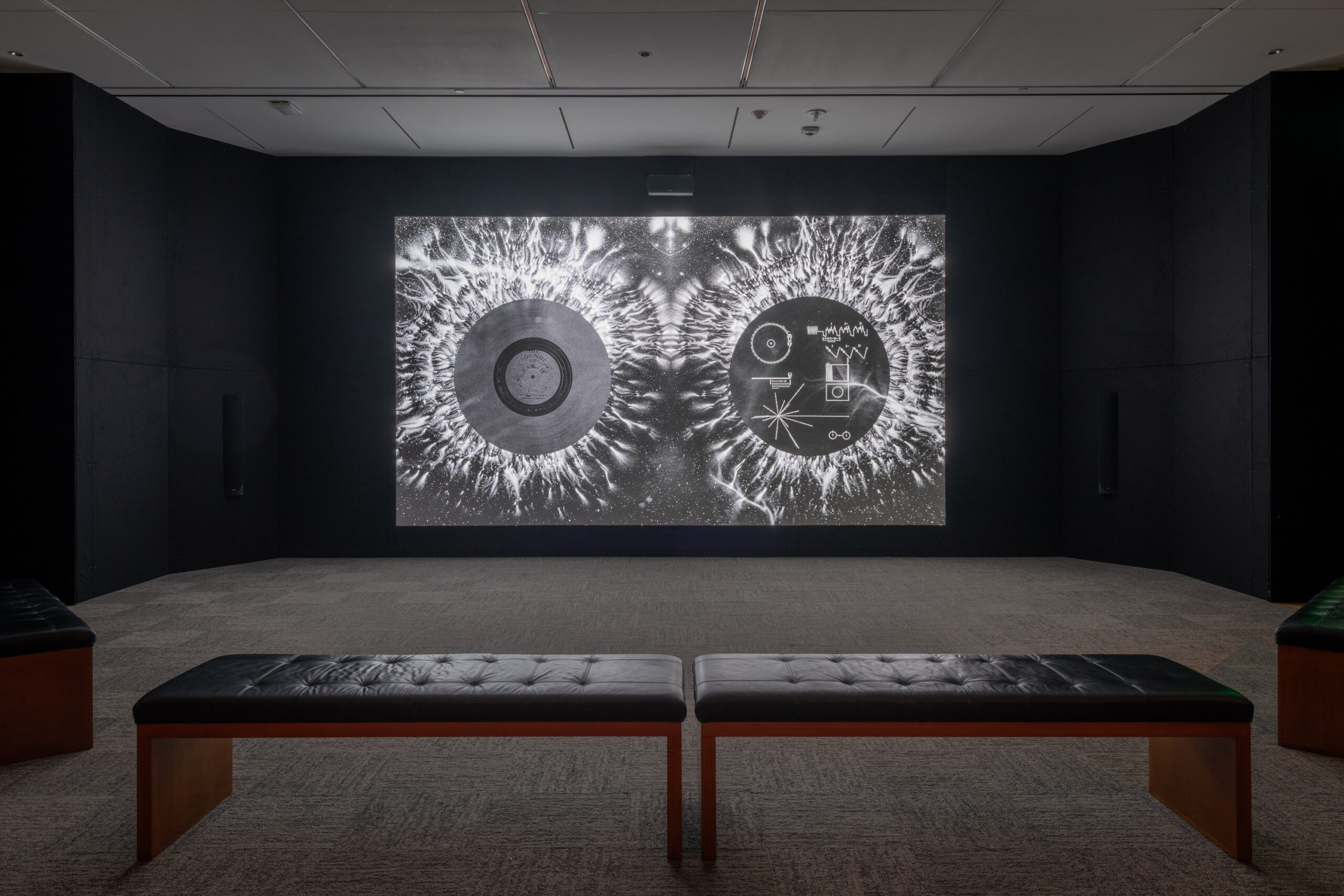

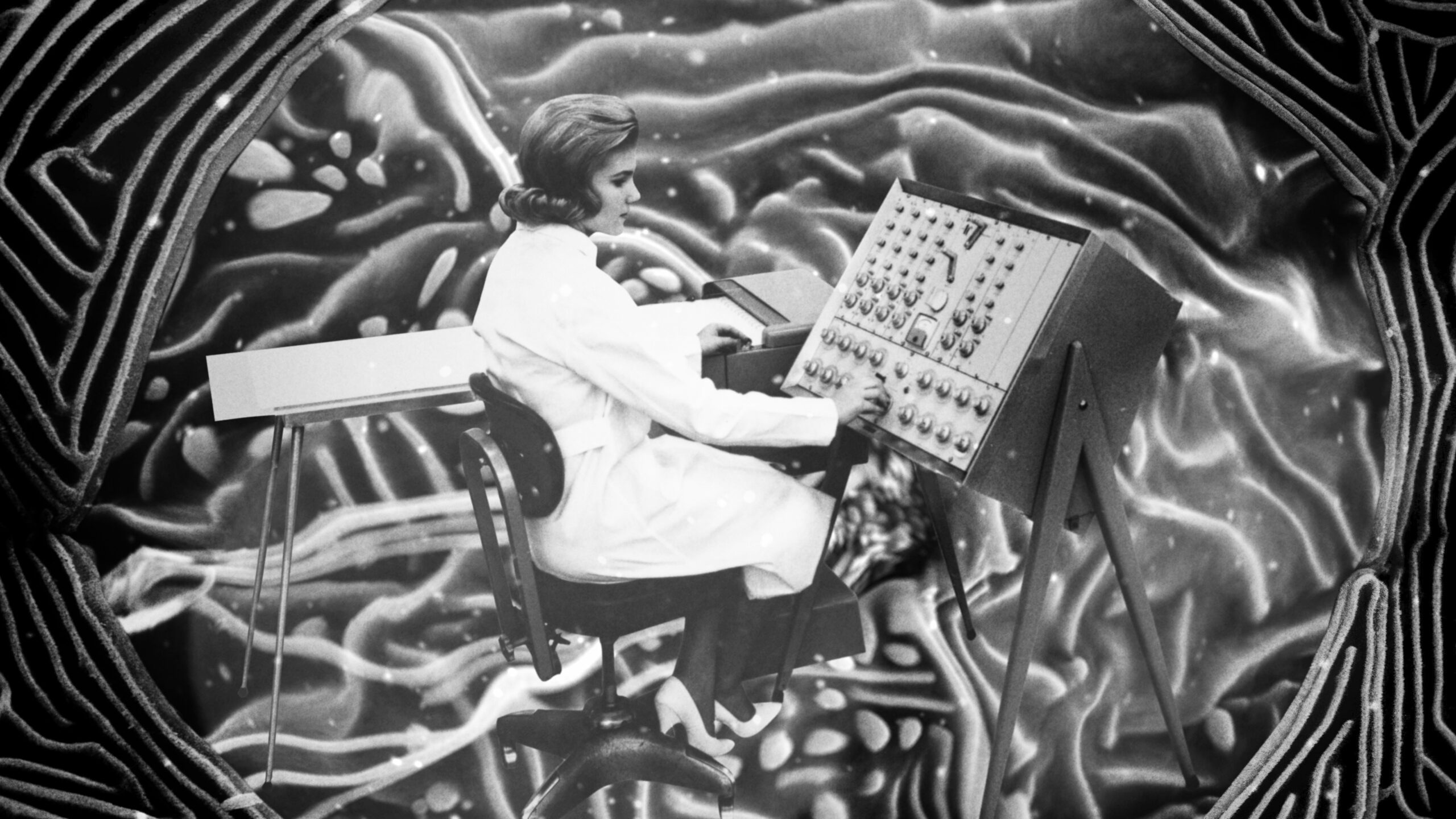

In the adjacent room, Ancient Beacons Long for Notice — the final film in a trilogy of movies co-written and produced by Robleto — explores the story of the Golden Record, a set of archival recordings about life on earth sent aboard NASA’s Voyager probe in 1977. As both a poem and visual feast, it showcases Robleto’s unique sensibilities with haunting beauty.

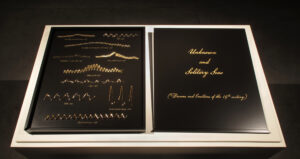

Speaking with Robleto during a writing retreat for his upcoming book titled The Heartbeat at the Edge of the Solar System: Science, Emotion and the Golden Record, reveals more. Robleto co-authored the book with Harvard art historian Jennifer Roberts. The book provides an in-depth exploration of Ann Druyan, the creative director of The Golden Record.

Generous with his thoughts, Robleto explores topics as expansive as his practice, including the nature of nostalgia, the potential for art to change the world and the notion that “radical empathy” might be the key to true connection.

Let’s hear more from Dario Robleto himself.

Dario Robleto Unplugged

PaperCity: A lot of your artwork is in dialogue with concepts of longing and nostalgia. You also connect things that don’t always seem like they should be connected. Do you agree with this?

Dario Robleto: On the point of nostalgia, I might not foreground it as the thing I’m exploring, but it’s always layered into my work. The term first arose as a medical diagnosis to identify the constant longing for home that arose from the horrors of World War I (what we now call PTSD). But the term has mutated into something very different in our time.

It pains me to think about oversimplified versions of nostalgia. For example, how the cataclysmic social, political and artistic complexity of the 1960s can today be encapsulated into a tie-dyed T-shirt.

Rather than being assumed to be a sincere, active engagement with complex ideas of loss, nostalgia is often seen as trivializing them. I see nostalgia as a powerful identification of trauma and an active call to heal it.

PC: Your work embodies an oscillation between longing for connection and acknowledging connection might be impossible. Does this go back to your impulse to connect things that seem unconnected, like whale ear bones and butterflies?

Robleto: There is joy in making the case that everything is connected. That the most disparate things, with the appropriate tenderness, will find their way to each other. When I approach unusual materials, I always ask, “What’s preventing empathy and connection through time and space?”

There are real consequences in how we treat each other when empathy is severed or seems impossible. On paper, Bob Dylan’s voice, butterfly antennae and prehistoric whale ear bones don’t seem to have much in common. But in each artwork I make, if I can find the connection between the most seemingly strange materials, then it expands, even if incrementally, the possibility that radical differences can be overcome.

PC: There is an anecdote in which you took a seashell to a honky-tonk. You let it listen to a Patsy Cline song at the jukebox, then put it back where you found it. Why?

Robleto: It is tied to my ideas of extending empathy through space and time and my philosophy of recording. It is a form of life after death. Perhaps immortality is not wrapped up in our ideas of a religious afterlife. Instead it is in the care the living display to the memory of the dead.

A vinyl recording of Patsy is a type of relic that can be reanimated each time it is played. The knowledge she held, and the heartbreak she endured, will always remain relevant as long as the living play and share the record. To lay her voice in the form of a seashell on the shore was to acknowledge that both their songs had been heard. I will also try to continue to learn from them.

PC: What you’re describing feels so important when trying to make meaning out of existence and not knowing. Your focus on the acts of living, not just its results, seems relevant.

Robleto: My mother is a huge part of this philosophy. She was the director of a hospice, so I grew up around hospice nurses. I always tell anyone who asks that my idealized model of an artist is a hospice nurse. It takes a unique set of skills that allows one to display love, care and dignity to a total stranger, with only moments to live.

Even the radical difference between life and death is no reason to suspend your efforts of love and empathy. The team behind The Golden Record, especially Ann Druyan looking for alien life, share similar skills as a hospice nurse. They must love something that perhaps cannot love them back. And yet, the not-knowing can’t be the reason they give up on this love.

PC: How remarkable is it that scientists in 1977 sent what you described as “perhaps the last will and testament of humanity” into space? They had little hope that anyone would discover it.

Robleto: I love The Golden Record, but I’m also a realist. No one yet knows if there’s anything out there to find it. Let alone if it can be deciphered. There are so many reasons why this experiment will most likely not work. But the point is they did it anyway.

That’s what makes it art. That’s what makes it an act of love. And that’s what I admire. Art creates the space for doing it anyway. I’m interested in how we can create a space that highlights that kind of action, not the result.

“Dario Robleto: The Signal” is on display at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art through October 27. Learn more about the exhibit here.

Author’s note: Brenda Melgoza Ciardiello is an artist, independent curator and writer based in Fort Worth. She holds a degree in Art History from the University of Notre Dame, a Masters in Education from The City College of New York and an MFA in Visual Arts from Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

_md.jpeg)