Texas’ Greatest 20th-Century Artist Finally Gets Her Due: Corpus Christi Museum Steps Up With Its Most Expensive Show Ever

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 12.07.16Dorothy Hood’s "Untitled,", late 1980s, at Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi (photo courtesy AMST, Corpus Christi)

THE ART MUSEUM OF SOUTH TEXAS IN CORPUS CHRISTI IS THE HOLY GRAIL FOR SEEKERS OF DOROTHY HOOD. CATHERINE D. ANSPON REPORTS ON THE LATE ARTIST’S FIRST-EVER — AND LONG OVERDUE — MUSEUM RETROSPECTIVE, WHICH OPENED THIS FALL, 16 YEARS AFTER HER DEATH.

If the powers that be were giving out awards for heroics in art history, that honor would go to writer and scholar Susie Kalil. Well-known in Texas art circles for her 2010 book about Alexandre Hogue (which coincided with a traveling museum retrospective she curated), Kalil is also remembered for co-curating with Barbara Rose the game-changing “Fresh Paint: The Houston School.”

The 1985 exhibit began at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, then traveled to two other venues including PSI (now a branch of MoMA, in New York) and is still considered a benchmark for shining interest upon Houston artists. Now Kalil is focusing on an artist who has the potential to once again be the breakout national art star from Texas: Dorothy Hood. For the past five years, Kalil and the Art Museum of South Texas have been single-mindedly committed to resuscitating the internationally exhibited Houston painter from the sands of time.

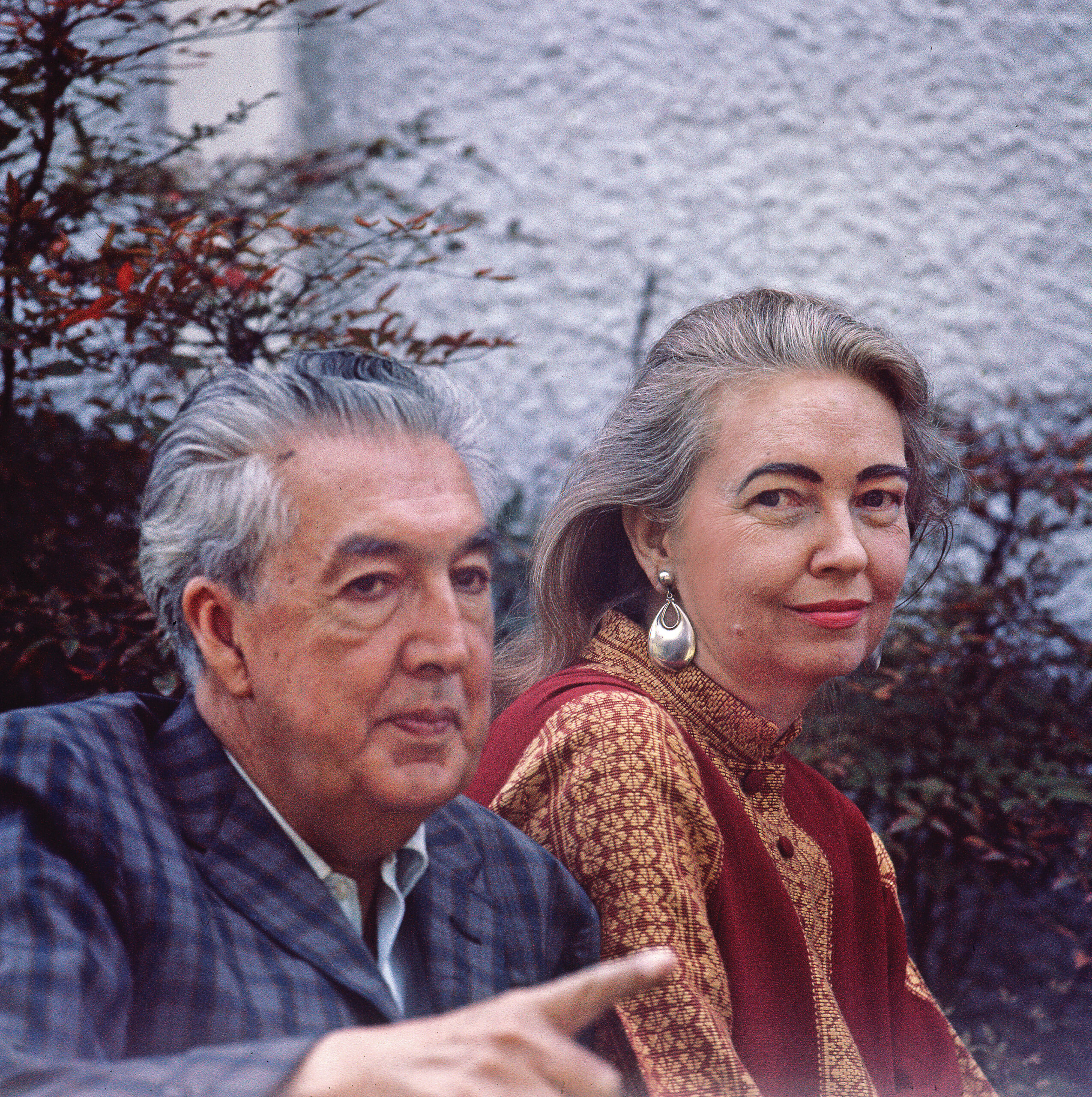

AMST is the repository of the Hood mother lode — her voluminous archive of paintings, collages, drawings, photographs, correspondence, all manner of ephemera, and even her ashes, as well as those of her husband, Bolivian composer/conductor José María Velasco Maidana, whose father was vice president of Bolivia.

The resulting exhibition, “The Color of Being/El Color del Ser: Dorothy Hood (1918-2000),” has taken over the Corpus Christi museum: 20,000 square feet of both the original Philip Johnson- designed 1972 building (the de Menils introduced Johnson to the museum trustees and played a part in making the commission happen) and the 2006 Ricardo Legorreta addition. The 155 works, loaned from museums and private collections throughout the United States., include the AMST’s cache of 54 Hood artworks; everything is detailed in Kalil’s lavishly illustrated, lyrically penned catalog published by Texas A&M Press.

An illustrated map and timeline of Hood’s travels, as well as vitrines filled with time-capsule materials including gallery announcements, letters, datebooks, and more bring the determined painter to life. After basking in the Hoods, one can easily make the case that Dorothy was Texas’ greatest 20th-century artist.

Her reach extended from California to New York, including representation in the Whitney and MoMA. Her double decades in Mexico, during the 1940s and 1950s, only add another layer to the equation, and interaction with seminal figures ranging from Pablo Neruda (who penned a poem to her) to Diego Rivera (she met her husband at his casa) and José Clemente Orozco (with whom she shared a studio), make the Rhode Island School of Design-student-turned-model worthy of a cinematic bio.

While the catalog and exhibit sidestep the controversy that marred Hood’s later years (especially the break with her staunchest supporter, gallerist Meredith Long, after she came under the spell of a scientist who was a questionable paramour), what remains — the artwork itself — is remarkable. The paintings are grouped in series, with many canvases reunited after being lost for decades. The presentation allows visitors to decipher Hood’s inspirations and follow her on the journey to depict abstracted, heroically scaled views of deep space (enamored of NASA, she was friends with astronaut Alan Bean) as well as cavernous oceans seen from above, rendered in pooling pigment.

Her collages, informed by mysticism and travels to world cultures (especially India) hold up well, but the delicate and surreal drawings and abstract, soaring color-field canvases are set to be Hood’s contribution to art history.

One hopes this exhibition will travel, especially to New York City and the West Coast, where the keepers of the canon may just allow Hood admission. After all, now is the time for both under-known African-American artists and women artists to be rediscovered, so the timing of “The Color of Being/El Color del Ser” couldn’t be better. There’s also a rumor that a form of this exhibition may be presented by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. And rightly so: When Maidana and Hood moved to Houston in 1962, she became one of the leading artists in a world dominated by big, brash male painters and also taught art at the museum school.

A photograph in the exhibition’s time capsule shows her as a member of the Houston Five — the only woman, alongside Richard Stout, David Hickman, William Anzalone, and James Boynton. (Hickman and Boynton have both passed on, but Stout and Anzalone still actively exhibit.)

Thanks to being picked up by gallerist Meredith Long in 1960, Houston first families became Hood collectors: Dominique and John de Menil, Fayez Sarofim, Nina Cullinan, John O’Quinn (a regular in her studio), Mavis Kelsey Sr., Carol Ballard, Isabel Brown Wilson, Diana and Bill Hobby, and Carolyn Farb — the latter, associate producer of a 1985 documentary on Hood, The Color of Life, which won the American Film Festival Award in 1987 and was supported by the MFAH.

Farb stepped forward early on to serve as underwriting chair of the retrospective — a seven-figure undertaking that is the most expensive, most ambitious exhibition ever mounted by the Art Museum of South Texas. It’s doubtful that another Hood exhibit of this depth and magnitude will ever take place, even if this show were to travel, so don’t miss Dorothy getting her due.

_md.jpeg)