Remembering Legendary Houston Artist Jesse Lott — Friends and Colleagues Recall a Beloved Phenomenon With Plenty of Heart

From the Project Row Houses to a Love For Sharing, Lott Created His Own Lane in the Bayou City

BY Ericka Schiche // 08.04.23Artists Jesse Lott and Angelbert Metoyer attended the Texas Artist of the Year Gala for Art League Houston's 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award, which was presented to Jesse Lott. Lott mentored Metoyer for many years. (Photo by Alex Barber, courtesy Art League Houston)

Writer Ericka Schiche reflects upon the death of Texas Artist of the Year Jesse Lott via conversations with seven art figures who knew him best, including two fellow co-founders of Houston’s Project Row Houses.

When a Houstonian thinks of Fifth Ward, certain things come to mind: The DeLUXE Theater, Burt’s Meat Market on Lyons Avenue, Mystic Lyon, Illinois Jacquet, The Jazz Crusaders and Don Robey’s Bronze Peacock club on Erastus Street. But the true embodiment of Fifth Ward was none other than Jesse Lott.

The legendary artist — who passed away this summer at the age of 80 — has left an indelible impact on the Houston arts community. Known primarily as an Urban Frontier Artist whose complex oeuvre includes papier-mâché works and sculptures, Lott changed myriad lives through sharing knowledge and creating art.

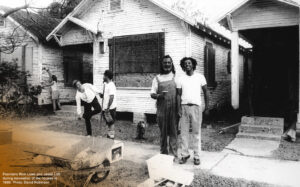

Born in Simmesport, Louisiana, in 1943, Lott settled with his family in Houston’s Fifth Ward neighborhood as a kid. In 1993, Lott helped establish Project Row Houses in the Third Ward with six other artist co-founders. Later, introduced by dear friend and artist Mel Chin, Lott received Art League Houston’s 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award. Just last year, Lott was named the 2022 Texas State Three-Dimensional Artist by the Texas Commission on the Arts.

Mentored by the late John Biggers, and later studying with Charles White at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, Lott fully embraced Blackness in art. He learned how to disconnect from Eurocentric paradigms in his thinking and work. A wise sage who was also erudite and professorial, he impressed many people with his intellect over the years.

A lesser-known fact about Lott is that he also loved music. Artist Angelbert Metoyer fondly recalls how Lott once brought out an upright bass into his studio, à la Charles Mingus, and began playing it. The bass was one of the instruments Lott excelled at, including guitar, the keyboard, piano and voice. In an interview with filmmaker Cressandra Thibodeaux, Lott sang a heartwarming rendition of Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Broke and Hungry” with his son Vida Lott, who survives him.

To illustrate the profound legacy Lott leaves behind, I spoke with fellow artists and friends of the Houston icon.

The warm familial connection between the late Jesse Lott and artist Mel Chin runs deep — two generations on each side. Chin’s late father, Chinese-American businessman Benny Chin, owned a corner store in Fifth Ward called the Wholesome Food Market. Chin noted how the word wholesome, in Chinese, translates to “good heart.” Chin told PaperCity, “I used to deliver the groceries to Mr. Lott, his father, on my bicycle when I was a baby. You know, a kid.”

Chin describes Jesse Lott as “a mystical kind of person who could see the needs of people.”

“He always loved how kids could learn from him,” Chin says. “And that’s why he saw value in the wire or the broken glass, or people’s memories. I think that’s what I’ll truly miss about him.”

Lott helped Chin install his See/Saw installation at Hermann Park during the 1970s. Both artists also worked together in the frame room at the now shuttered Robinson Gallery. Inspired to create another installation, Chin decided to “flood the gallery with water and put this sand in it. Make it like a beach inside.”

Chin laughs at the memory, but says Jesse Lott was “a man of great strength” who often loaded a wheelbarrow with sand to help him create the installation.

Artist Susan Plum was also part of the group known as The Rats (Robinson Art Team) at the gallery directed by the late Ann O’Connor Williams Harithas. Plum knew Lott and Harithas, his main champion, since 1975, and notes “their bond of friendship was forged by their shared love of art and community.”

“Jesse Lott — a dear friend to so many, a man with a natural love of community, an artist who shared his knowledge, mentored many whom have gone on to be very successful artists and offered a hand when anyone needed it,” Plum notes on Lott’s passing.

Plum expresses that Lott “left a tremendous legacy, not only of a brilliant career as a real maestro and artist, but also of a Bodhisattva. Jesse made a practice of unconditional love, which is felt by our entire community and experienced in his art.”

Lott’s recent public-art sculpture The Dreamcatcher, made for the Sunnyside community, embodies what Plum believes is Lott’s view of compassion and beauty.

“I feel he left us not in sorrow, but in joy,” Plum writes. “I am certain he is feeling the great expansiveness of his quantum leap he has taken. Bring it on home, Jesse!”

With Lott’s death, only four original artist founders of Project Row Houses remain: Floyd Newsum, Rick Lowe, Bert Samples and George Smith. Transitioning before Lott were James Bettison (1957 to 1997) and Bert Long Jr. (1940 to 2013). The renovation of 22 shotgun houses, also known as row houses, blossomed into an ongoing community-oriented cultural project. Now in its 30th anniversary year, Project Row Houses continues to be a beacon in the Houston community.

Jesse Lott, a Genius of Texas

Artist Floyd Newsum, who met Lott during the 1970s, tells PaperCity he will miss Lott’s “free spirit. That wealth of knowledge.”

“I’ve always considered him the genius of Texas in the arts, since he was a Renaissance man,” Newsum, a professor at the University of Houston-Downtown, says. “He could do so many things. And everything he did turned into gold.

“Jesse was such a human being. He really was an example for humanity. He was a gentle giant. The kind of person that, if you met him, he would teach you something. And it doesn’t have to be art related. He’ll teach you something about life. A lot of us will miss him.”

Rick Lowe, a MacArthur Genius grant recipient and artist represented by Gagosian Gallery, says Lott deeply inspired him, describing him as “a leader in the ’80s.”

“There weren’t a lot of known Black artists in town at that time, and he was one,” Lowe notes. “He played such a strong role in the broader arts community. He became somebody that I looked up to and I wanted to be next to.

“But his biggest influence to me, though, was his incredible support of my interest in developing Project Row Houses. His wisdom, his outlook on life, and his commitment to community reinforced my desire to push that project forward.

“Jesse’s motto was that everybody could produce art. His intention was to teach anybody who was willing to learn and wanted to learn.”

Lowe explained how Lott encouraged him to return to the studio and resume his painting career.

In addition to Lowe, Lott also mentored and inspired artist Angelbert Metoyer for many years. They developed a close bond. Metoyer describes Lott as both a sensei and maestro.

“He is now a part of the air we breathe,” Metoyer says. “It’s one thing that makes him a living soul — it’s the thing that makes his soul the living.”

Metoyer tells an intriguing story about a visit to Lott’s studio.

“I went over to Jesse’s studio to help clean up the yard in front of the building,” he describes. “While we were moving things around, Jesse said, ‘Hey, there’s a nice patch of sun over here’. Then he said, ‘I’m going to teach you a lesson.’ And he brought out these really nice paintbrushes from sizes zero to nine, and he said, ‘I’m going to teach you how to paint a figure using a different brush for every part of the body’. . .

“I just heard Jesse, in my mind, say ‘Go head, Jo Jo!’ ”

What began as an art lesson later morphed into a lesson in serendipity.

“He brought this really nice paper and laid it all down,” Metoyer says. “Then he brought out some watercolor paint and black ink. And we went through the process of painting the figure. He did the first one so he could demonstrate it to me. Then he had me do the second one as a demonstration to him that I saw what he taught me. We did the third one with the color.”

Metoyer, who flew into Houston from the Netherlands the day Lott passed away, describes it as a fortuitous moment.

“A train came by and started blowing the horn,” Metoyer says. “And he (Lott) started laughing, but I couldn’t hear anything because of the train. Right when the train horn was blowing, it started raining in this one spot where we were painting. And Jesse looked at me. He started laughing, saying ‘Well, go head! Now God is painting with us.”

Metoyer laughs while recalling his mentor’s words.

“My first instinct was to move the paintings before they got messed up, because we were painting with ink and watercolor,” Metoyer says. “But Jesse said, ‘Leave it there’. He turned around and got something to drink out of the studio. We came back, and the rain stopped.

“And we left the work out there to dry. He said, ‘Those are finished. Let’s start another series.’ For me, that is the beginning of what I do. It’s that word: phenomenon.”

His voice trailing away in tears at the end, Metoyer says, “If you could use a word in relation to me and Jesse, it’s this word: phenomenon. Phenomenon is what Jesse’s work is about and what he brings into people’s lives. He teaches through phenomena.”

Dr. Alvia Wardlaw remembers Jesse Lott as a “selfless, kind and funny individual who led from behind.”

“As a curator, I appreciated the wonderful integrity of his work — the honesty that combined humor with this monumentality,” Wardlaw tells PaperCity. “That always struck me. When you saw a piece by Jesse Lott, instantaneously, you knew that it was him. He carried his genius so lightly, and he put all of that effort into his work.

“He was so accomplished in so many ways that he didn’t even talk about.”

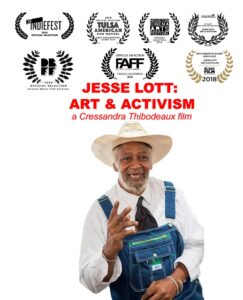

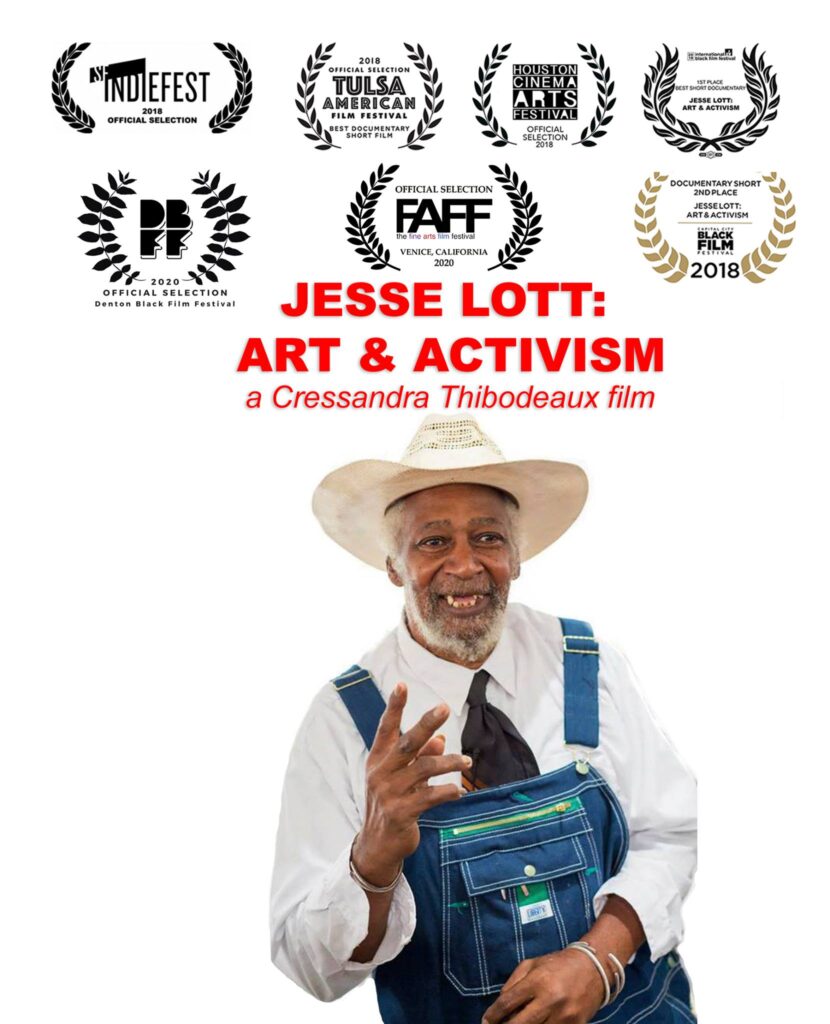

Lott also inspired filmmaker and 14 Pews Founder Cressandra Thibodeaux to rethink art history. She created a documentary entitled “Jesse Lott: Art & Activism” along with students from her 14 Pews Film Academy.

“He inspired me because he made me think of the Renaissance being inspired by the Motherland of Africa,” Thibodeaux says. “He helped me think of the importance of African art, and how it should be part of the dialogue.”

In the documentary, Lott explains the power of art. Referencing the influence of John Biggers, he stated, presciently:

“When you do a work of art, you have a greater possibility of reaching more people than when you write a book. Because the history books will be burned, and the history will be mistold.

“But the art is there to be interpreted by each person, every time they look at it. You can tell many, many, many different stories with one picture.”

A tribute event honoring Jesse Lott will be held on Thursday, October 5 from 5:30 to 7 pm at The Silos at Sawyer Yards. A Sculpture Month exhibition “The Sleep of Reason: The Fragmented Figure,” which features Lott’s work and that of his sons Vida Lott and Wayne Myles, will be on display at The Silos at Sawyer Yards, from Saturday, October 7 through Saturday, December 2, with a public opening set for Saturday, October 7 from 6 to 9 pm. Learn more here.

Jesse Lott’s art is represented by Deborah Colton Gallery, Houston.

_md.jpeg)