Artist Known For Voluptuous Women Turns His Sights on Men — a New Type of John Currin Show

Why Painting Guys is Different, the Mount Desert Island Life and a Big Dallas Moment

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 09.03.19John Currin and wife Rachel Feinstein at home in NYC, 2011. (Photo by Lee Clower for The New York Times)

John Currin’s Mannerist and Northern Renaissance-style canvases startle and transgress in their disquieting depictions of contemporary women, distorted figures of pin-up voluptuousness that elicit admiration, envy, even outrage. Now, his male subjects are being examined in “My Life as a Man,” at Dallas Contemporary — his first American museum show in 15 years.

We rang the artist at his summer place in Mount Desert Island, Maine, to discuss the occasion.

Summer life.

We’re in Mount Desert Island, the same island that has Bar Harbor. The kids are going to day camp here. My wife, (artist) Rachel (Feinstein), and I have studios, and we can work during the day. And it’s pretty wonderful.

We’ve actually been coming here most summers since the mid-1990s. We’ve bought a house, and we’ve built studios. It’s become a very important part of our family’s life. We spend at least two months here a year.

How the Dallas Contemporary exhibition come to be.

I’ve known [curator] Alison Gingeras for many years. She came up with the idea independent of me. . . I used to do slide lectures for other artists at what was called Kamp Kippy, a kind of artist’s retreat in Maine.

I was doing lectures every year, and I ran out of subjects. I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll just do a slide lecture of all my men images.’ Weirdly, around the same time Alison approached me about doing a show of all men. I guess it was on both of our minds. But Alison is the one that really came up with an idea to do men as a show. It was probably four years ago.

On you and Dallas.

I did a lecture at SMU in 2010 and was very pleasantly surprised. I’d been to Dallas once as a little kid, to go to the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame in Fort Worth.

I had one painting in a show at the Meadows Museum at SMU [in “Spanish Muse: A Contemporary Response”], which I believe is going to be in the Dallas Contemporary show; it’s called Rippowam, which is an Indian name. It’s a doughy looking blonde guy and a somewhat exotic, dark-haired woman sharing brandy. That was the only time I’ve been to Texas in my professional life.

In terms of the current climate and the larger conversation about gender, it’s interesting to show the men as the bookend to your women.

I’m not sure whether it’s gender or sex. But I think I’ve always painted men as a kind of escape from when painting women starts to seem overdone to me — and cloying — and I can’t seem to empathize.

Normally I feel like I empathize more with women and women as characters and as personas in a painting. But sometimes it breaks down, and I think that’s when I paint the odd man. I don’t know whether the men are self-portraits; they convey something very different for me emotionally than the women do. But it’s often to take a break from painting women that I paint men.

Painting men is just a completely different experience for me than painting a woman. The woman sort of comes out naturally — and the reverie is almost automatic. With men, it’s like pulling a tooth. It’s more difficult. And stranger.

It’s just a completely different set of motivations. It’s not as pleasurable as painting a woman, but sometimes it’s a lot funnier. Because I consider men ugly on the surface. Perhaps that’s part of the motivation. How do I make a beautiful painting out of man? That’s always been my question: how to make a beautiful painting out of flawed material.

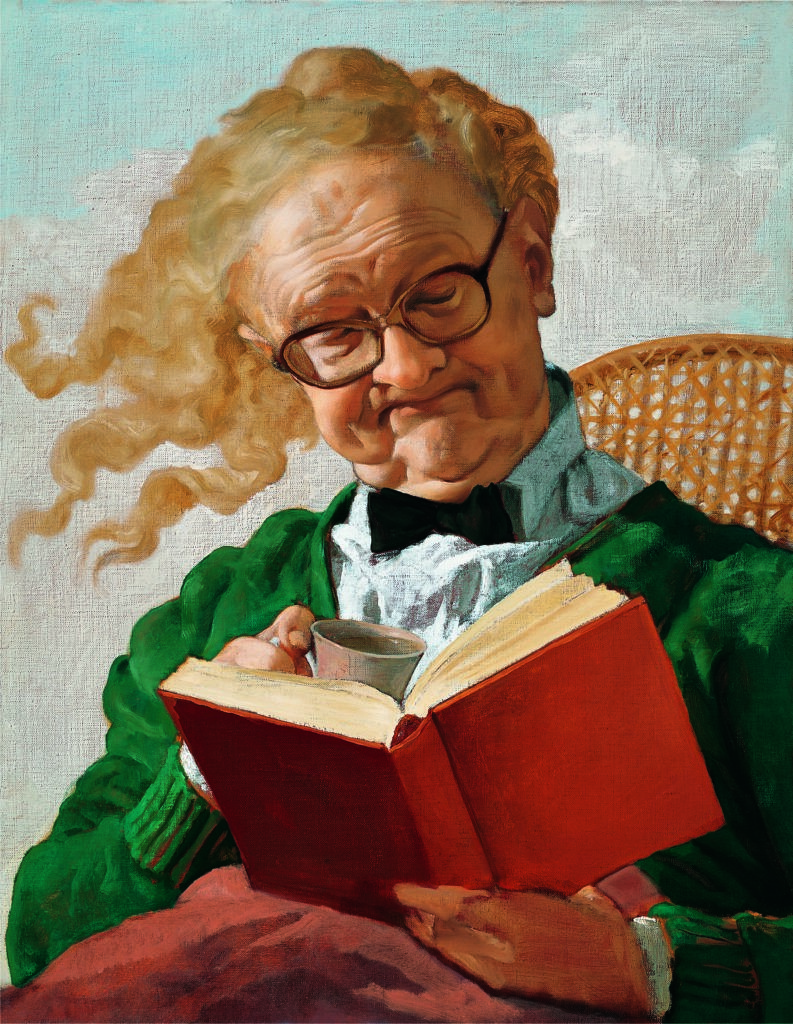

Looking at some of the pivotal paintings in the Dallas Contemporary exhibition, what are we to make of 2070. Is that a self-portrait?

God, I’d be lucky if I made it to 2070. The conceit was that it was my son in 2070, my 15-year old son, Francis. Although he’d be a little too young to look like that in 2070.

He’s got Mr. Roger’s sweater. It’s sort of a timeless painting. Also very Norman Rockwell.

[Laughing] I found the picture in a stock catalog. I guess I gave him heroic hair, like a Greek god. I wanted him to be sort of pharaonic. That’s why I put him up in the sky.

Looking through the other images, Fishermen is fascinating. How do we decipher that canvas?

I don’t really expect people to figure anything out. It’s not a puzzle like that. But I can tell you that the picture came from a dream I had. As it happened, I’d been sharing a studio for over a decade with my friend, Sean Landers, a painter. Sean and I had just separated. For the first time in my adult life, I had a separate studio from Sean. As I was making the painting, I thought I should put Sean in there as well. It was sort of an elegy for Sean and our shared life as artists. Kind of a farewell. Well, I still see Sean, but we used to paint side by side.

Are you the figure on the right, with darker hair?

I’m the figure on the left, which I painted with some kind of complicated mirrors. I also liked the idea of painting a seagull. I thought of a rich person who sails. They’d have paintings of birds, seafaring pictures. I wanted to invoke a certain type of painting. It’s really a painting about me and Sean. And art and life. It’s just incidental that it has this narrative. That’s why the fish are anthropomorphized and have human expressions. That’s the Greek chorus, I guess — that pile of fish. It’s not really about fishing.

The Kennedys is a very odd panting. You’re showing a male and female aspect of the president. Now, 20 years after it’s painted, people are trying on different gender roles.

None of my paintings are intended to make a direct social statement. It may be inadvertent, but I don’t intend it. The Kennedys came about from another dream I had — I don’t often have dreams that I turn into paintings, but in those two cases, Fishermen and The Kennedys, those were vivid dreams.

I dreamed I saw a painting of two Kennedys, and they were sort of on a Dust Bowl farm, like a Margaret Bourke-White photograph, like an old 1930s farm couple.

When I was a kid in the ’60s, you’d see all these portrait busts of Kennedy, and they’re all done in that kind of rugged, crusty style. In the dream, the painting was done with the palette knife, crusty paint on the face.

I felt compelled to make the painting. But the painting goes deeper for me than that. Not so much in terms of the plot or my intentions, but as a painting and as an odd thing, a kind of compelling and beautiful thing.

I didn’t know much about Kennedy. I went to a bookstore and got a bunch of books and picked some pictures of Kennedy I liked. In doing the painting, I had these books lying around, and ended up reading all about PT 109, and as a side note, I got really interested in Kennedy.

The significance of John F. Kennedy was more, I think, as a figure from my childhood. Maybe thinking about my parents or thinking about my parents’ politics, or thinking about the social world and politics when I was a little kid. So weird. Unconscious politics, I guess.

Also, for me, the face of John F. Kennedy is a kind of deity. I guess the word is icon. I was compelled to paint it as a startling image of masculinity. Very unusual and very particular; an image of masculinity from very, very early childhood. Maybe a sort of alternate father figure.

But again, even though I painted the painting, I’m still only speculating on its meaning. I’m not in control of its meaning. I’m only in control of its making.

I feel that with figurative art — and with all art — you’re not in control of what it will mean to people. You’re just rolling the ball down that hill, and then watching where it will go on its own. I only know what I set into motion. I’m not in control of what happens after that.

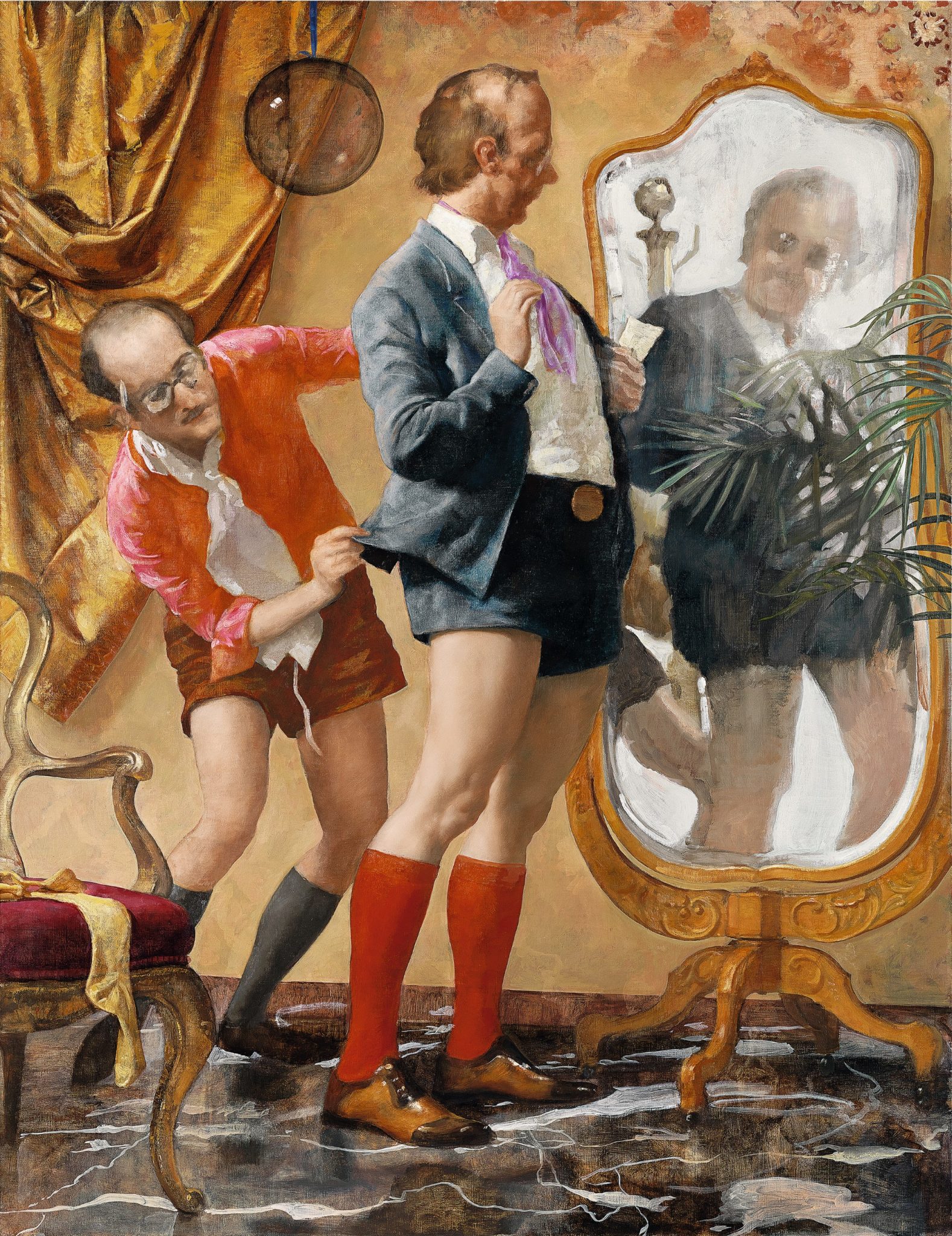

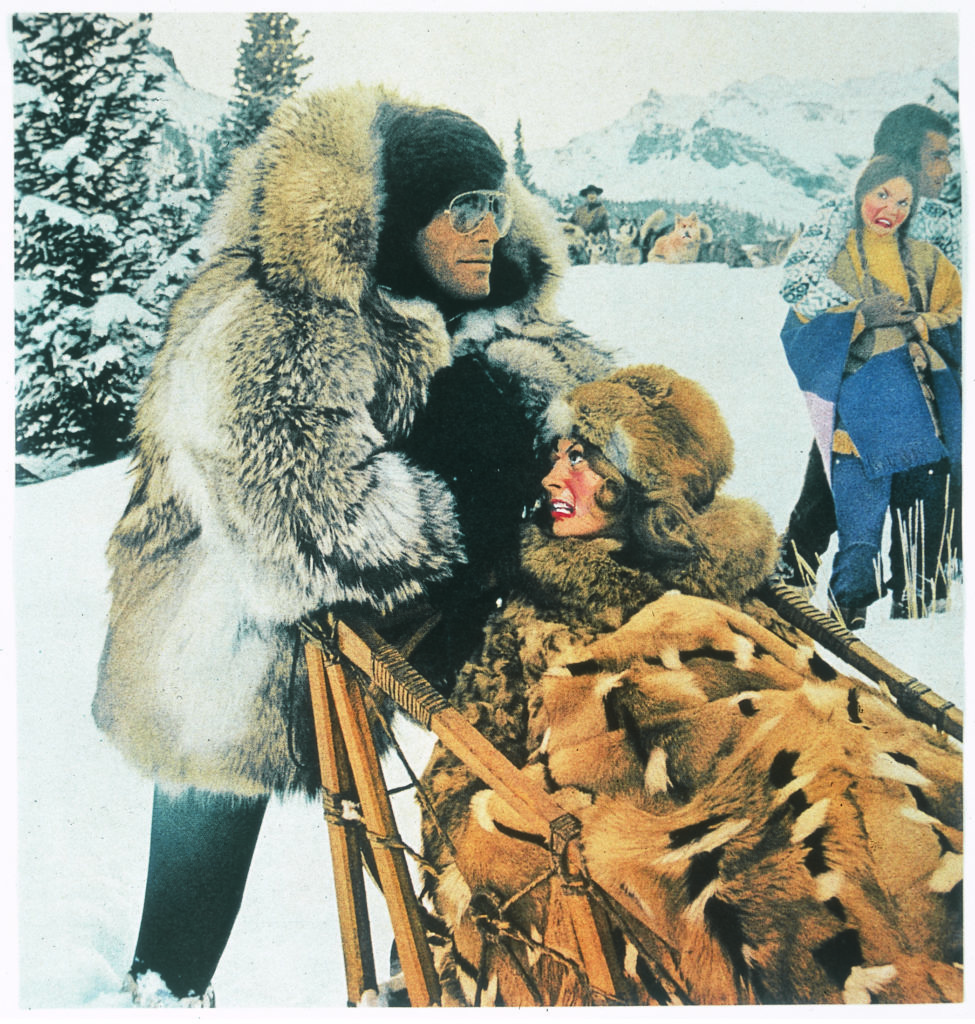

Let’s talk about another work coming to Dallas, Hot Pants.

Part of the appeal of Hot Pants is the image, which was from a fairly well-known cigarette ad — I think it might have been Camel — from when I was a little kid. Some of that is the creation by the copy editor at the ad agency who made it up. But, for me, it’s my memory of that ad. I remembered it, and then lo and behold, I found it, and I thought: It’s a painting waiting to be made.

That painting is weird because it started as a very funny, open-hearted painting, and I think it ended as a very, very solemn and somber painting. That wasn’t my intention, or in my control, but that’s what happened.

I think that’s one of the reasons it’s a good painting. It shows three options for manhood. I kept that in the back of my head as I was painting it. That image of the man being attended to by a tailor, looking at his mirror image, just felt timeless and monumental. That’s why I painted it.

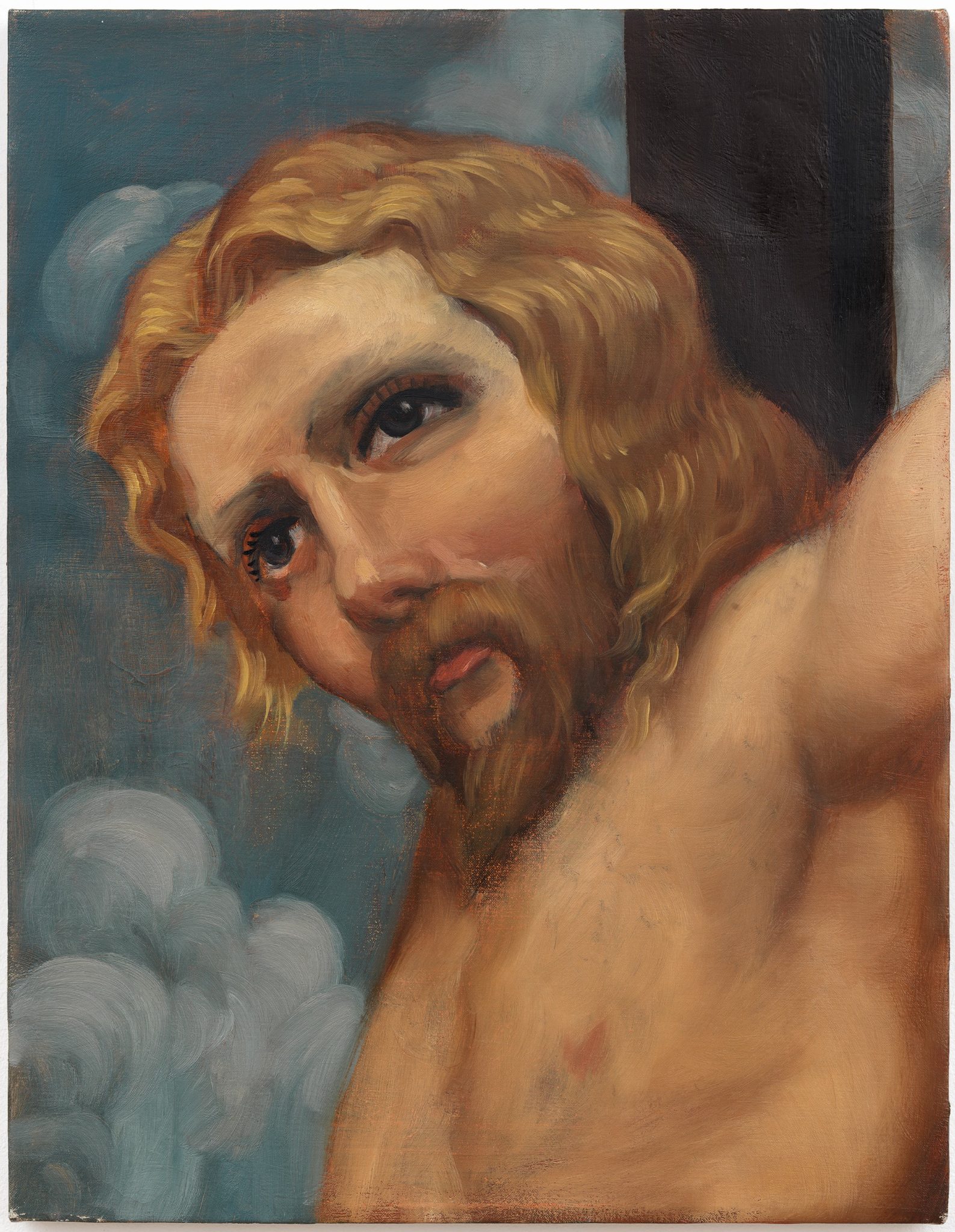

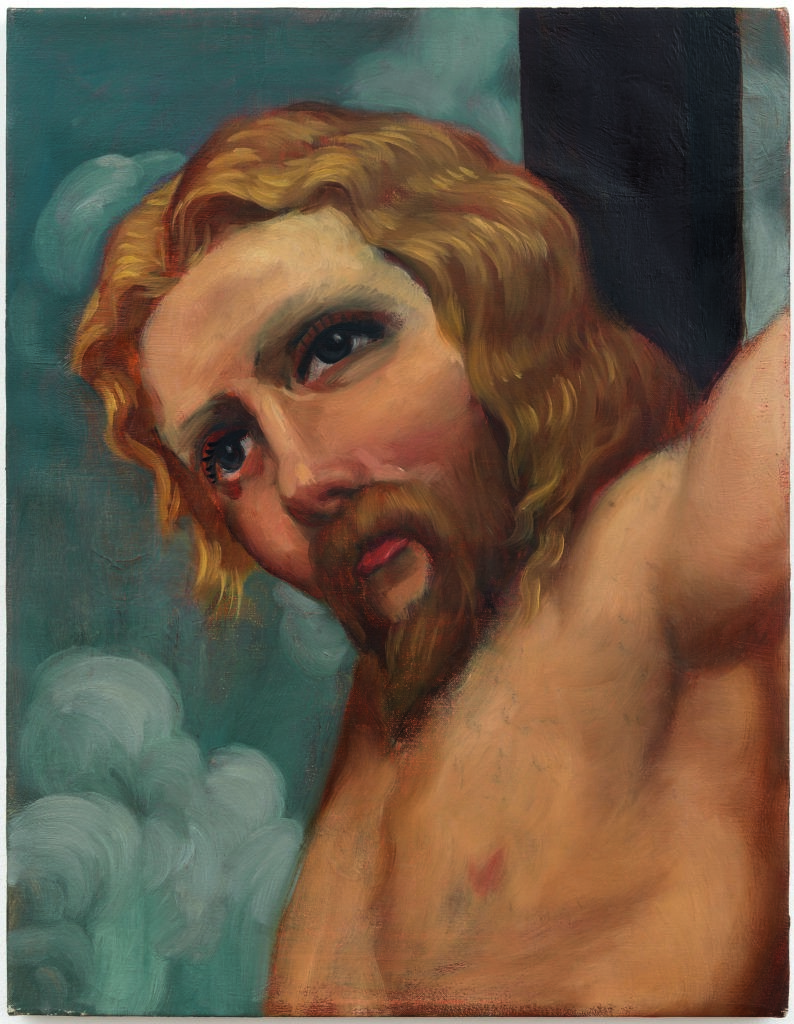

Then there’s a painting of Jesus Christ in the show — is that your portrait?

Yes, the oil drawing with the mustache. Part of me thinks it’s funny. It’s meant to amuse myself. If you’re a painter, it’s also one of the great images to paint. You can paint Jesus, you can paint naked ladies, you can paint a beautiful waterfall.

There are certain things that are just meant to be painted. I was reflecting on how that could be an image made now. What does it look like to have a regular-looking guy, instead of Jesus, on a cross. It wasn’t meant to be blasphemy or mockery — it was more a kind of comment on the ridiculousness of painting figuratively nowadays. And just to amuse myself, and see what it would look like.

Let’s finish up with The Jackass, which feels like Warren Beatty.

Those were ads in Playboy magazine. They showed a handsome, successful guy with women adoring him. I didn’t really invent those things — they’re works of art in their own right by the production designer and the photographer — but I did think it would be interesting to make all the women hate the guy instead of loving him. The image of a completely unperturbed man being hated rather than being adored.

What was it like to time travel and see all your early works come together for this show.

I recently did a show with Gagosian Gallery of my sketchbooks through the years. It was just after my father passed away. It was one of those weird, reflective times. And just seeing things I hadn’t laid eyes on in 20 years was a very strange experience.

Any show of your old work carries that kind of hazard, and interest, and gift. Then my mother died. So I’m in the mode of thinking about my childhood. And I’ve been talking to my wife about this. She’s been reading Carl Jung a lot, and she’s trying to get me to read it.

Your father was a physics professor and your mother a piano teacher. Were they pleased you became an artist.

Yes, I think they were happy. To some extent, I realized this after they both died: They were an important part of my audience, in a strange way, both in a positive and negative way. I was trying to please them and trying to anger them at the same time. I didn’t realize how much my motivations had been colored by what I perceived their reaction would be — whether they would hate it or love it or be ashamed of it or be proud of it, or whatever.

On your practice and the provocative.

Much of my motive when I’m making a painting is to recapture that sense of surprise in an image when you were a child. That’s one way of explaining why I’ve done a number of socially provocative things. They were really just to surprise myself and to recapture that wonder of childhood. That includes frightening images, unpleasant images, pornographic images, mean-spirited images, all kinds of things.

Thinking about the persistence of one’s childhood and the persistence of the images that you’re first exposed to, and the strange ways that they appear anew as you age — and that they keep surprising you. In some ways, as an artist, I think you try to surprise yourself with images in the same way they surprised when you were a child.

That to me is one of the motivations in exploring sexual things. I’m not making a comment on society’s sexuality; I’m exploring my own feelings. I don’t have any special knowledge, apart from being a person.

And, in terms of speaking to people who have asked me about #MeToo … Being neither a victim nor a perpetrator, I don’t think I have anything interesting or important to say. I would offer that I think the sexual revolution that started in the ’50s and ’60s has reached a milestone and is either reversing or something happened. I think it is very, very big. Much too big for me to understand. That’s another reason I have an urge to make pictures — to ruminate over these kind of things.

Your plans for when you’re in town for the Dallas Contemporary opening.

I don’t know if my family’s coming, because they have to start school. I don’t know if I want to disrupt them. I’ll probably be with Rachel, my wife. I’m just hoping the show is good. If I sleep in a sleeping bag in a closet, I just want the show to be beautiful.

You’ve exhibited at the Frans Hals Museum in the Netherlands, juxtaposed with Dutch Golden Age painter Cornelis van Harlem. What would be your next dream pairing from art history?

Oh brother. My ambitions are more centered on making paintings. What happens after I make them is up to whether people like them or not. My big dream is to make a beautiful painting. Exhibiting is kind of a privilege after that. My ambition is what I’m going to make, rather than where I’m going to show it.

Ideal day.

Here in Maine, making something very nice in the studio, finishing by 7:15, walking down the hill, and taking a swim with my children. I’ve managed that about four times this summer, so it’s not impossible.

Most surprising about you.

Oh gosh, I’m actually really, really, really focused on painting. I think I’m pretty boring outside of that. I like fast cars, and I like old movies, but basically it’s all painting all the time.

“John Currin: My Life as a Man,” September 15 to December 22, at Dallas Contemporary, dallascontemporary.org.

_md.jpeg)