Listening To The Painting — Self-Taught Houston Art Star LaMonté French Riffs Like a Jazz Musician To Challenge History

The PaperCity Interview

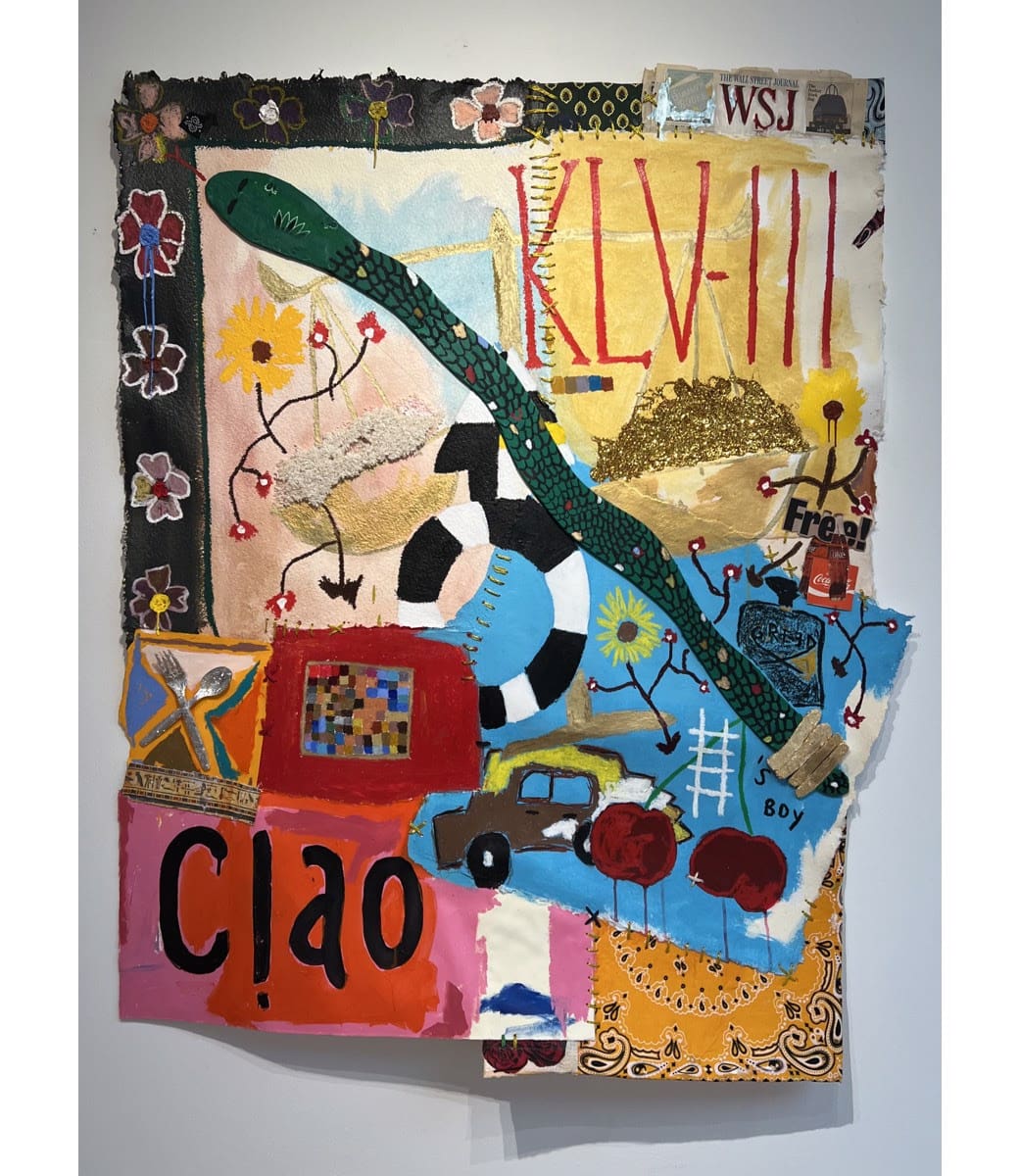

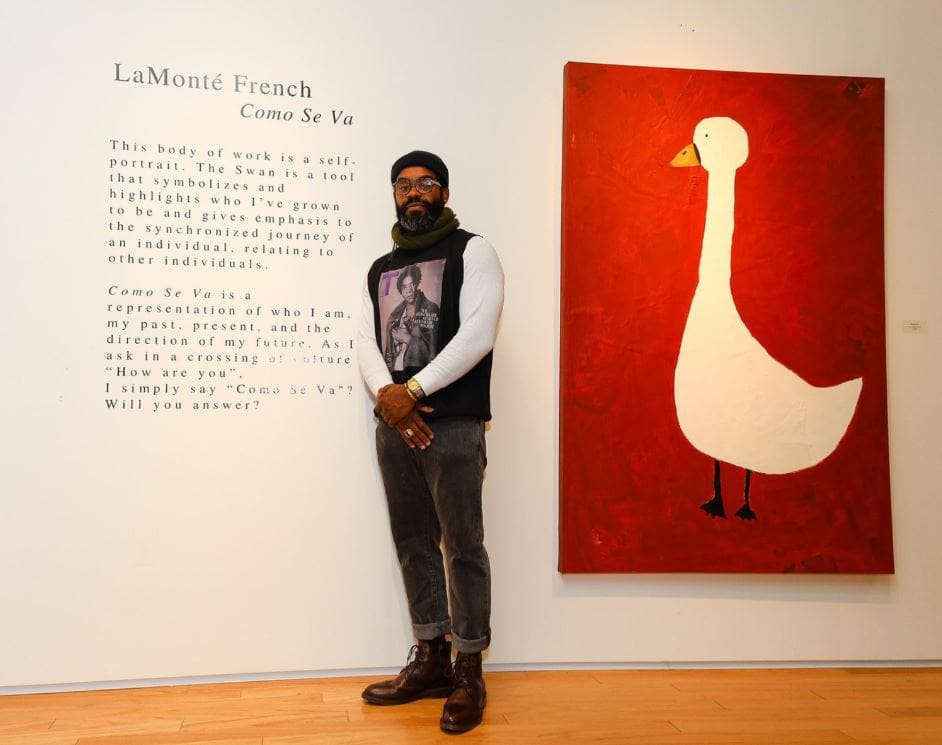

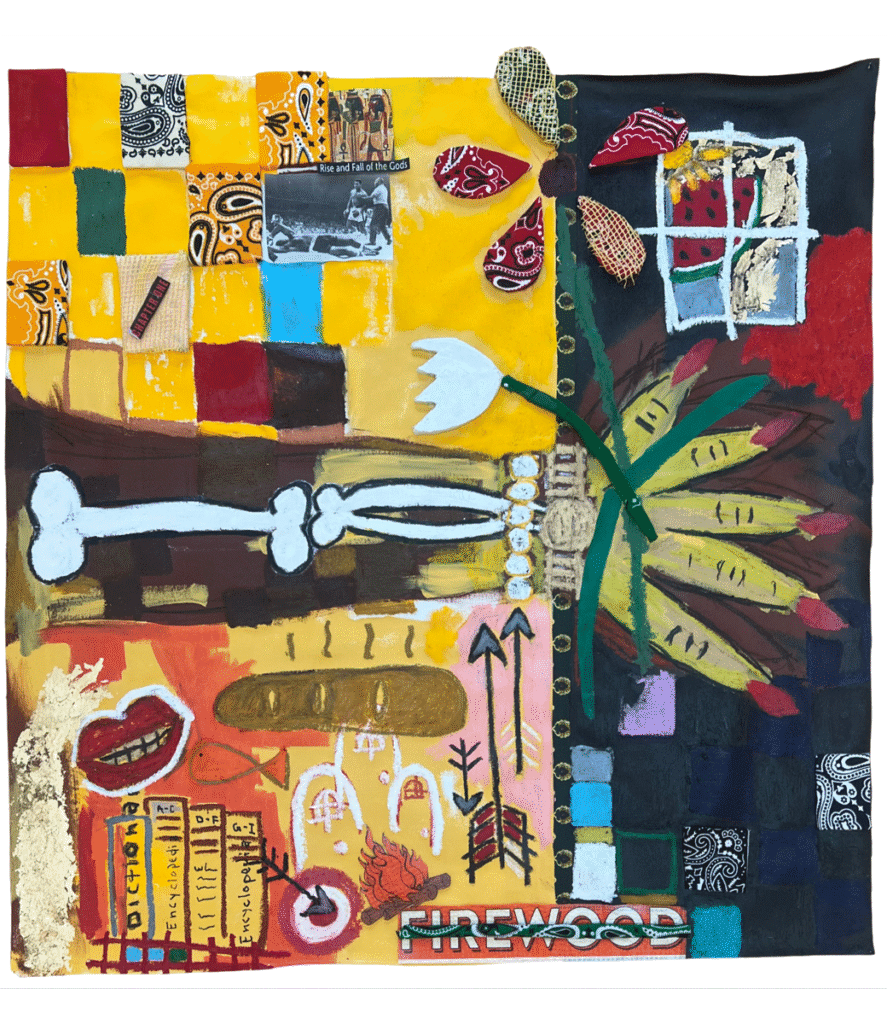

BY Alison Medley //Houston abstract expressionist, Lamonte French, unveils Como Se Va, featuring the symbolism of the swan which illustrates his transformative journey.

When abstract-expressionist LaMonté French talks about the art of creating a painting, he muses with a wide, knowing smile, as though he’s listening entranced in pure synchronicity to the John Coltrane’s In A Sentimental Mood. French even describes the lure of the painting, personifying it as though it is a demanding partner or girlfriend.

“My day usually starts by waking up around 11 am or 1 pm,” French says. “Once you’re into making a painting, it commands attention. It’s almost like being a clingy partner or boyfriend, or girlfriend. You have to be in front of the painting. You have to listen to it.

“You might spend six hours with it. And, there’s always music. It could be jazz, rap music. It’s about consuming myself in my own thoughts. But it’s about balancing everything. You dig into some demons.”

LaMonté French’s work isn’t ornamental. His luminous paintings in French’s 2025 exhibition Ça Va Bien command a deeper response. They draw you in and elevate your consciousness. French’s work is an unflinching rumination on America’s layered injustices — brutal, bold and haunting.

The Houston-born, fully self-taught contemporary artist — who humbly still refers to himself as “just a Creole kid from Houston” — has composed exhibitions that, like the jazz he reveres riffs and ruptures its way toward truth.

LaMonté French’s work will be featured in the Summer Group Exhibition at Ellio Fine Art in Houston on Saturday, August 2, from 4 to 6 pm.

“I paint my dreams,” French says. “They’re all over the place. But there’s a flow, stanza to stanza, like jazz.”

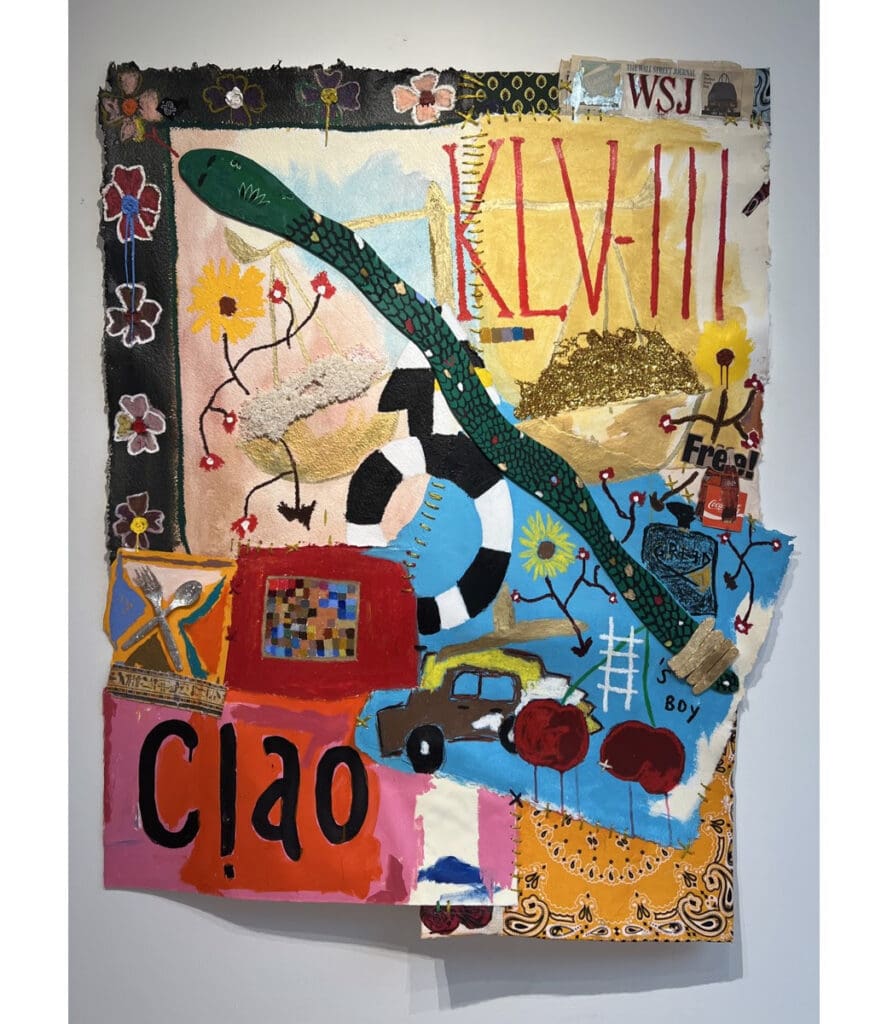

Through vibrant collage layered with symbolism, French confronts identity, memory and survival with the same directness he talks. What he questions about America will resonate.

“As an artist, I make work with my hands,” he says. “And I’m just a storyteller, but the difference is I try to take the ugliness of the story and restore the beauty.”

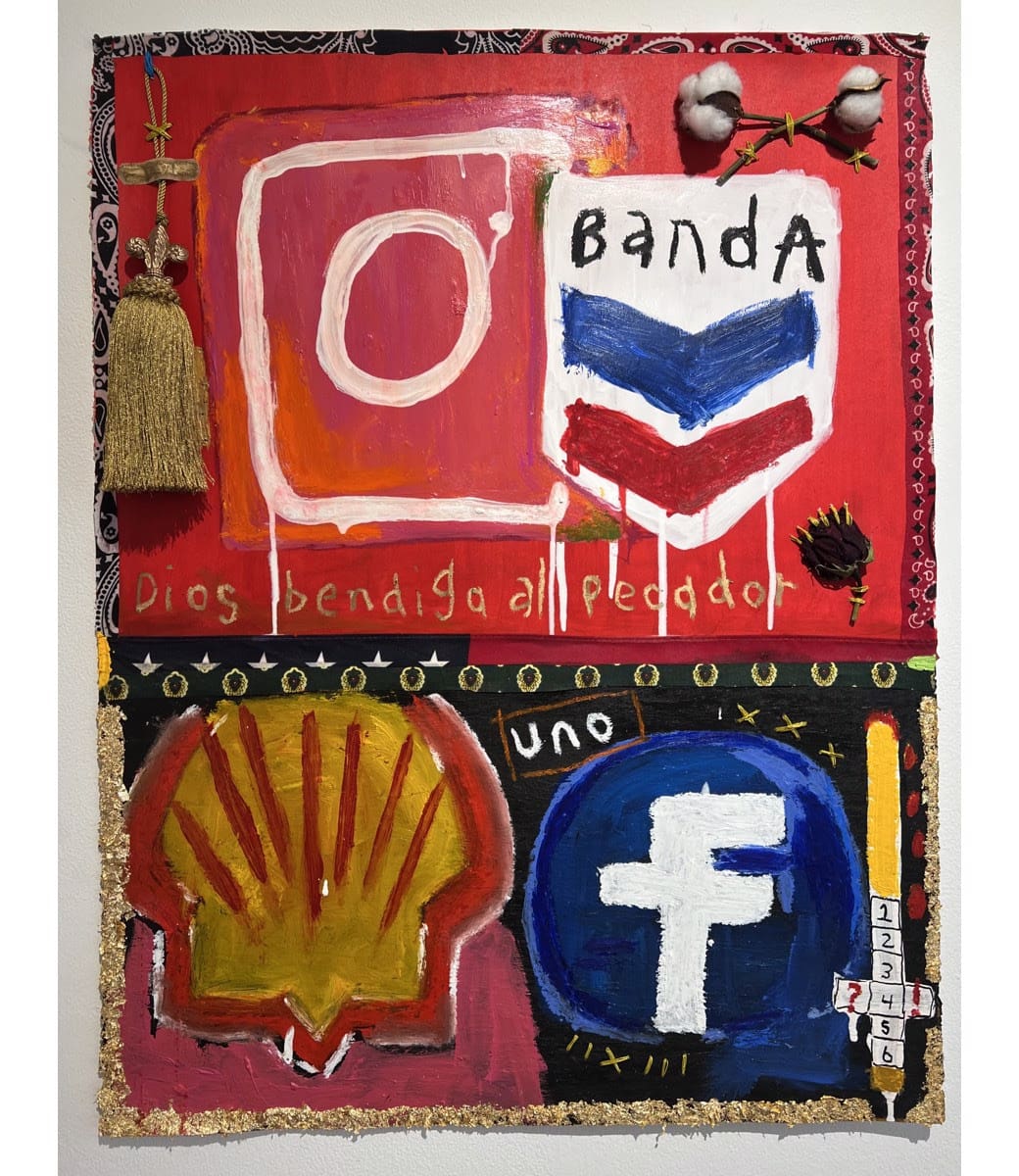

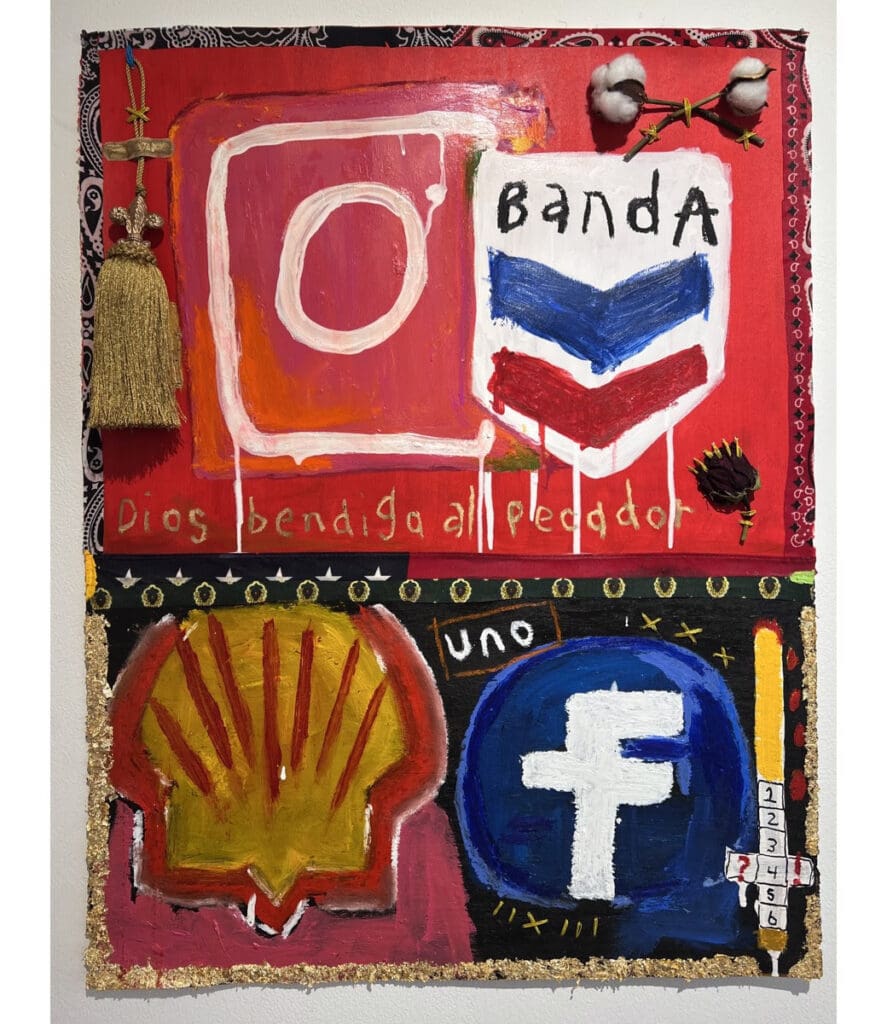

The fluidity is interwoven in French’s work. In “Triple Entendre: Civil War/Crips & Bloods/Gang Violence,” gang symbology overlaps with Civil War iconography, a tassel hinting at graduation. Or perhaps revolution.

“America throws rocks and then it hibernates,” French says. “It’s to a point where they want to put a sheet over the history of what this country was built on — stolen land with stolen hands. In the work, ‘America, we have your DNA,’ The Confederate Flag was literally made from the American flag. If you have a conversation with people in the South, it may seem like they’re divided, but many are on the same side. It’s all about perspective. If you get closer to this flag, this Confederate Flag, you’ll see it’s the American Flag.”

Raised in a household steeped in the love of athleticism, French broke away to discover his own form of endurance — painting.

“As a kid, I was always creative. My father was a celebrity when I was growing up,” French says. “I was raised in a certain atmosphere. I would inquire about the color of my skin, and I learned about Martin Luther King Jr.”

The impeccable chic of LaMonté French’s mother deeply influenced him. Her distinctive sense of fashion and color palette pushed French to be just as expressive.

“She loved fashion, and her color palette was opulent,” he tells PaperCity. “She was always very put together. Her sense of fashion encouraged me and pushed me to be expressive and be different.”

French’s painting “Hand of Dora Maar” is not so much a celebration of fashion as it is a critique of vanity.

“Vanity sometimes exposes you,” French notes. “All the perils of what you’re reaching for — if you are reaching for a certain status. Her arm is tattooed with Louis Vuitton Damier, yet her bone is exposed because sometimes vanity and status will expose who you really are on the inside. When you’re transparent, you cannot hide.”

French’s first solo show FUEGO sold out in under 24 hours — a precursor to the momentum he rides now.

LaMonté French Rides The Creativity Waves

Right before the exhibition of Ça Va Bien, French endured a stretch of illness and creative stagnation. But then, his creativity re-emerged even stronger.

“A painting will tell you when to take a break,” French says. “Sometimes you just need to listen to a painting. Or it will say, ‘Hey, I need a little more love today.’ Or it might say, ‘Hey, don’t touch me today.’ I always say the paintings make themselves. You just have to listen.”

Ça Va Bien is described as “a sharp reflection of the world we live in. How history lingers, how systems shape identity, and how survival becomes an art of its own.” Indeed, through bold color, layered textures, and symbols drawn from both childhood and culture, French presses us into engagement. Who gets to tell history? Who is seen, and how?

“You as an artist a part of the process,” French says. “You’re a part of the balance. The story has to be told, and it’s not just the story of the technique.”

That pressure to reclaim narrative is central to his creative practice. He draws from his Creole roots, the elegance of his mother and memories of invisibility. “My father was my first muse. I started summarizing books, then drawing what I saw,” French reminisces. That progression — mimicry to mastery — is encoded in every layer of Ça Va Bien.

The swan, which recurs through French’s work, becomes a kind of self‑portrait.

“It’s the story of the ugly duckling,” French says. “But it’s also me. It’s about being misperceived. Then becoming something revered, beautiful. I think about the journey that the swan has to go through, from the start to becoming this icon of beauty and elegance.”

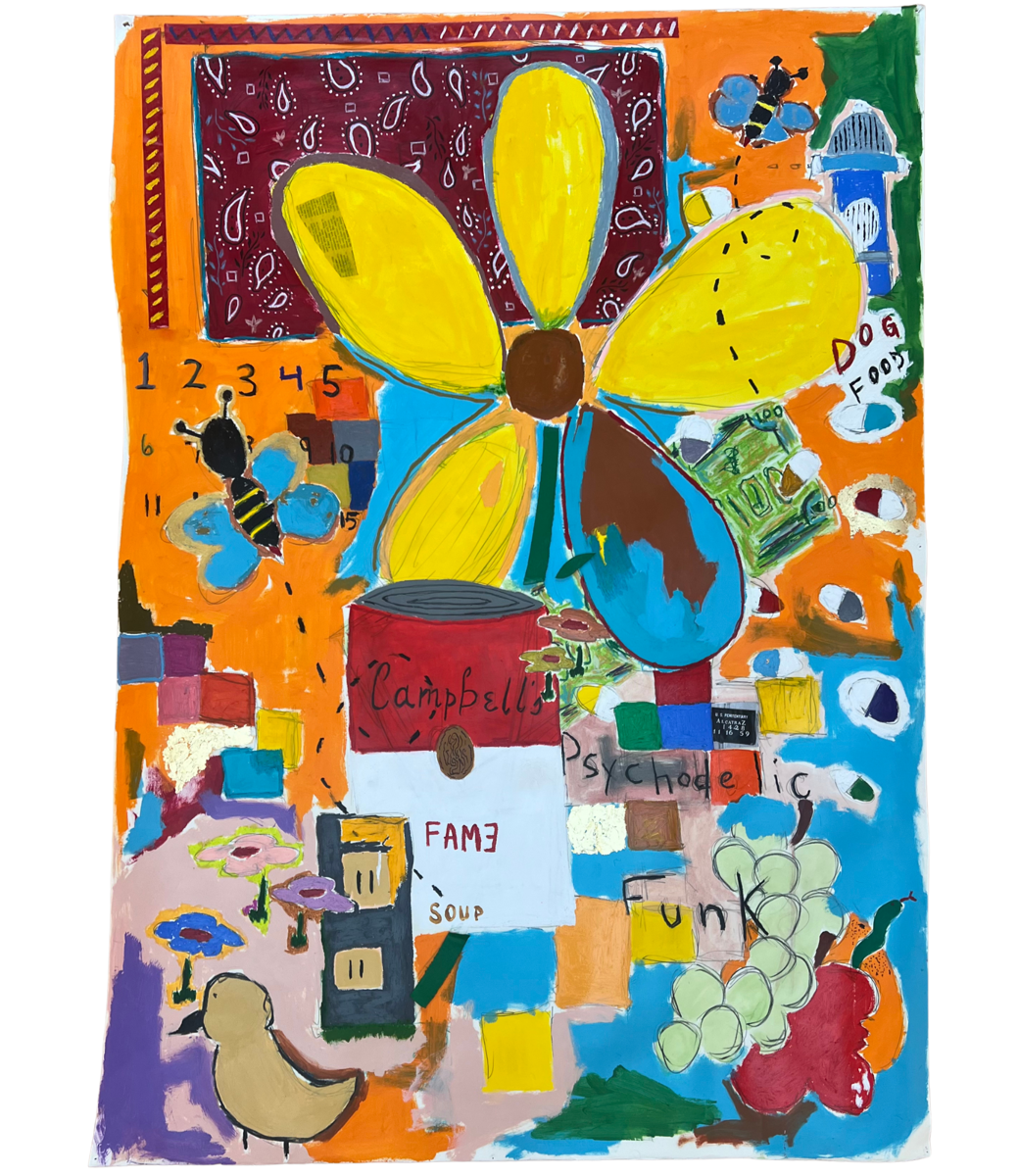

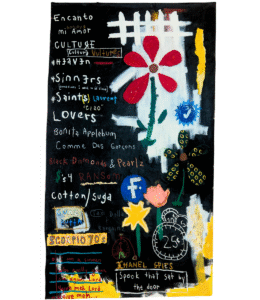

There’s a sense of living in dreamtime–a raw subliminal awakening in French’s “Journal Entry One Thousand. “This piece is a representation of my dreams, the place where all of my experiences, whether they have happened or what I foresee are stored,” French says. “This work is a dialogue of my inner thoughts, a visual deposit into my journal. It gives homage to the peaks and valleys in a world of gumbo adventures and melancholy moments which seem like despair.”

In the work entitled, “Flowers of Truth Lie in Ripened Fruit,” LaMonté French embraces how we look back on time.

“This piece gives beauty and praise to being resilient,” he notes. “It stands on the shoulders of a people who overcame and pushed through. When something surprises us, it expresses how the flowers of truth lie in ripened fruit. This work is a memorial, a love letter, a flag to the culture of being proud with grandiose and opulence. It is a symbol of triumphs after layered tribulations.”

Ellio’s earlier exhibition Como Se Va (Feb‑Mar 2023) already showcased French’s flair for “lux complexity” through layers of collage, mixed media and content. But Ça Va Bien unveiled in early 2025 marked his most politically charged and formally ambitious moment yet.

“When you look at something like this exhibition, all of this is a conglomerate of one dream after the next,” French says. “You take all the events and make them co-exist. It’s important to figure out how to make those things fit. You have to be resilient, and you have to persevere. You have to keep pushing. That’s what you have to keep your eye on.

“You will take some bumps, bruises. You have to have tough thick skin, but you must persevere.”

Like Theolonious Monk or John Coltrane, LaMonté French works in rhythm.

“Everything in life is based on rhythm,” he says. “Even if you’re a corporate executive. If you’re in rhythm, then everything is on. The rhythm can last for years. When you’re in that rhythm, take that moment and execute. You have to ride that wave.”

The Influence of Jean-Michael Basquiat

French cites Jean-Michel Basquiat as a formative influence — both in spirit and in technique. Like Basquiat, French fuses raw emotion with coded visual language, layering color, gesture and form in a way that resists easy interpretation. He’s drawn to Basquiat’s ability to create works that are not just seen but felt.

“I first fell in love with art through Jean-Michel Basquiat,” French says. “For collage, it’s all about the detail in which Basquiat has been able to compose these stories and to take these contrasts, color palette and merge them as one. He’s able to tell these stories without words.”

Ultimately, French doesn’t offer catharsis so much as clarity. In an America where culture is commodified and memory is malleable, his work insists on uncomfortable truths — rendered gorgeously.

“You take the ugliness of the story and restore the beauty,” he says.

It’s an aesthetic — and an ethic — that sets French apart. He isn’t simply creating paintings. He’s composing visual poetry of survival.

His study of celebrating human rights is both a spiritual process and an act of resistance. Part of a generation treating painting as altar and archive, French wrestles with systemic ghosts while building something indelible.

“Being an artist is my way of being immortal,” he confesses. “This is my way of giving a part of history to the universe.”

_md.jpg)

_md.jpeg)