Working for Houston’s Most Important Art Dealer: Life at a Legendary Gallery’s Anything But Simple

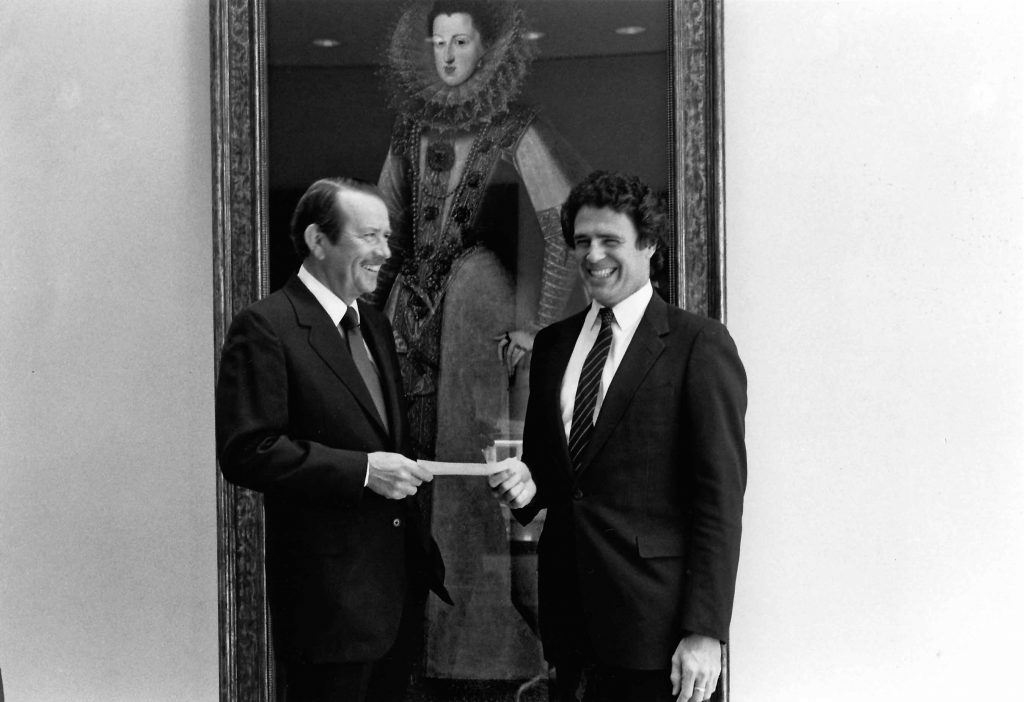

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 04.30.17Meredith Long, second from left, with American Association of Museums brass at the gallery’s opening night for the benefit loan exhibition “Americans at Home and Abroad,” March 26, 1971

It seems like yesterday, but it was actually 28 years ago that I nervously answered an ad — and was hired — for a gallery position at venerable Meredith Long & Company. It was my first big break in the art world and the first time I seriously applied my art history degree to both living artists and those from the textbooks — Inness, Marin, Sargent, Motherwell, Krasner, Stella.

The man in charge of these important artworks was impeccable — and intimidating — but would become an important mentor. I sat at one of the gallery’s two front desks as a junior and wide-eyed, greeted visitors of significance who shaped Houston’s cultural institutions (all of whom were clients — Edward Albee, Lynn Wyatt, Mr. and Mrs. David Wintermann, and Fayez Sarofim). In my subsequent career as an art writer, I attended innumerable exhibitions at the gallery.

Recently I returned for a series of interviews with Mr. Long, conducted over a month-long period this past winter and early spring. The occasion was a momentous anniversary: 60 years as Houston’s top gallerist of American art.

It would not be possible to compare Meredith Long to another Houston dealer — his influence, vision, and sphere of authority best parallel someone of Leo Castelli’s stature. And, like Castelli, Long has always been a man of ethics, action, and his word. During my time with the gallery, ML, as staff called him, had open heart surgery.

The day after surgery, he summoned the accountant to the hospital to sign and dispense checks; the gallery paid rigorously on time, and for years every artist who brought in canvases — including standard bearers such as William Anzalone (the Round Top-based landscape master, still in the stable 50 years later), University of Houston art department head Richard Stout, and sporting artist Jack Cowan — were paid for works even before their paintings found collectors.

My favorite anecdote dates from 1989, my first year at the gallery. After a New York-based client had committed to buying a $20,000 bronze sculpture by Michael Steiner (equivalent to six figures in today’s economy) and sent in an initial payment, he changed his mind. With trepidation, I had to give Mr. Long the news. Without pausing, he said, “Don’t worry about it, kid. There will be another collector.”

On smaller matters however, he could be very stern — over-ordering sodas for an opening, or the protocol for placing calls on his behalf. Everyone snapped to attention when he entered the gallery, and the sense of being part of something formal and important kept the staff slightly on edge, yet proud and inspired to do our best.

Everything at the gallery was done a certain way. Everything was approved by Long — and still is: gallery invitations and the handsome catalogs that were its calling cards, artist selection and exhibition installation, collaborating with museums on scholarly volumes and shows. Clients were trusted and respected. Gentlemen and ladies merely signed for works, which were sent on approval to their homes, delivered and placed so the client could test-drive the art.

The honor system ruled, and payments were sent in a timely manner after a sale was finalized. Openings were old school — and still are: 5 to 7 pm, valet parkers, passed cocktails as well as nice wines from Richard’s.

Then there’s the roll call of artists and exhibitions presented across the decades. Each memorable in their time, even more so looking back — a bounty of works, many of them masterpieces by the greats, which would be challenging and extraordinarily expensive to present today at a museum, let alone a gallery. One example is portraiture by turn-of-the- century expat John Singer Sargent — canvases that rendered society kings and queens in luscious surfaces and Grand Manner poses.

His depictions provided windows onto a certain caste and character. “Thanks to Meredith Long, there are more Sargents in Houston than in any other place in the world,” late Museum of Fine Arts, Houston director Peter Marzio remarked upon the occasion of a 2010 museum exhibition of “Houston’s Sargents,” placed alongside the traveling show “Sargent and the Sea.”

The roundup of stately portraits owned by Houstonians and purchased through Meredith Long totally eclipsed the visiting exhibition. Nineteenth and early-20th-century notable painters Frederic Edwin Church and Mary Cassatt had their day in the gallery. The former was celebrated in a museum-quality display of his sweeping landscapes, on the occasion of the galleries 50th anniversary in 2007. Opening night was capped by a dinner, a fund-raiser for MFAH’s American department, held at the tony Bayou Club.

In 2010, Long partnered with another blue-chip American gallerist, Warren Adelson, to present a rediscovered cache of American Impressionist Mary Cassatt’s exquisite, understated works on paper, a high point in the annals of the gallery history. The exhibition was shared between Adelson’s Upper East Side gallery and Long’s River Oaks bastion.

The gallery also carved out special turf for sporting paintings and prints. No one owned sporting art in Texas like Meredith Long. His name and that of artist Jack Cowan will forever be intertwined, beginning in the early 1960s.

To Cowan’s works, Long added Al Barnes and Herb Booth; the trio were involved in every significant commission and conservation organization, documenting hunting and fishing trips, some with former President Bush (41), thus recording a way of life and a landscape that has either vanished or is under siege.

Among contemporary masters, the late Kenneth Noland (known for his compelling targets) stands out. Long relays a hilarious episode where Noland and some of the Color Field painters came to visit and they all went hunting. He rushed them away from the field and on to dinner because many of them were not skilled with a shotgun. Noland also proposed to his girlfriend, Architectural Digest editor Paige Rense, in the gallery during his opening. “She was a marvelous woman,” Long remembers.

Helen Frankenthaler of the limpid Color Field abstractions — one of the best abstract artists in the last half century — was also a staple and represented ambitious gallery programming that was ahead of its time. Recently I was browsing the gallery’s ample library and found a Frankenthaler catalog for works on paper exhibited in 2004 that is utterly sublime.

I remember being asked to “Get Helen Frankenthaler on the phone!” I quaked at the thought of dialing up a living legend, but somehow rang up the studio and relayed a message on behalf of my boss.

A contemporary artist whom Long has championed throughout his career is ’80s and early-’90s darling Donald Sultan. Thirty years ago, Sultan’s minimalist, large-format drawings of charcoal eggs or flowers rendered against a white background represented a radical brand and a return to a brooding realism.

Selling a pair of Sultans for five figures each during Art Chicago in 1989 was my first big break as a gallery fledgling. I was also involved with placing an epic, six-figure Sultan oil-and-tar-on-linoleum painting shortly after the fair.

In the 2000s, the artist seemed to have lost some of his early luster, but now his massive, environmentally tinged canvases, edged with a sense of the apocalyptic, seem right for our time. Long represents Sultan to this day. Nearing 90, Long has slowed down a bit — no international travel, focusing instead on trips to his Hill Country ranchand occasional hunting forays — but remains indomitable, with wit at the ready.

Every afternoon, as he’s done for the past 60 years, he presides over and conducts business at the gallery. The day of our photo shoot, he was entertaining captains of industry and trustees of boards over drinks, conversation, and art. “It’s a dude party,” Martha Long says. She and a staff of three oversee the daily operations of the gallery, in close collaboration with her father.

Martha has been at the gallery for more than 20 years. A gifted athlete with many triathlons run, she is the youngest of a brood of seven shared by Mr. Long and wife, Cornelia, as well as the only child from their marriage. The other six, like a patrician Brady Bunch, form a blended family, three each from the couple’s previous marriages.

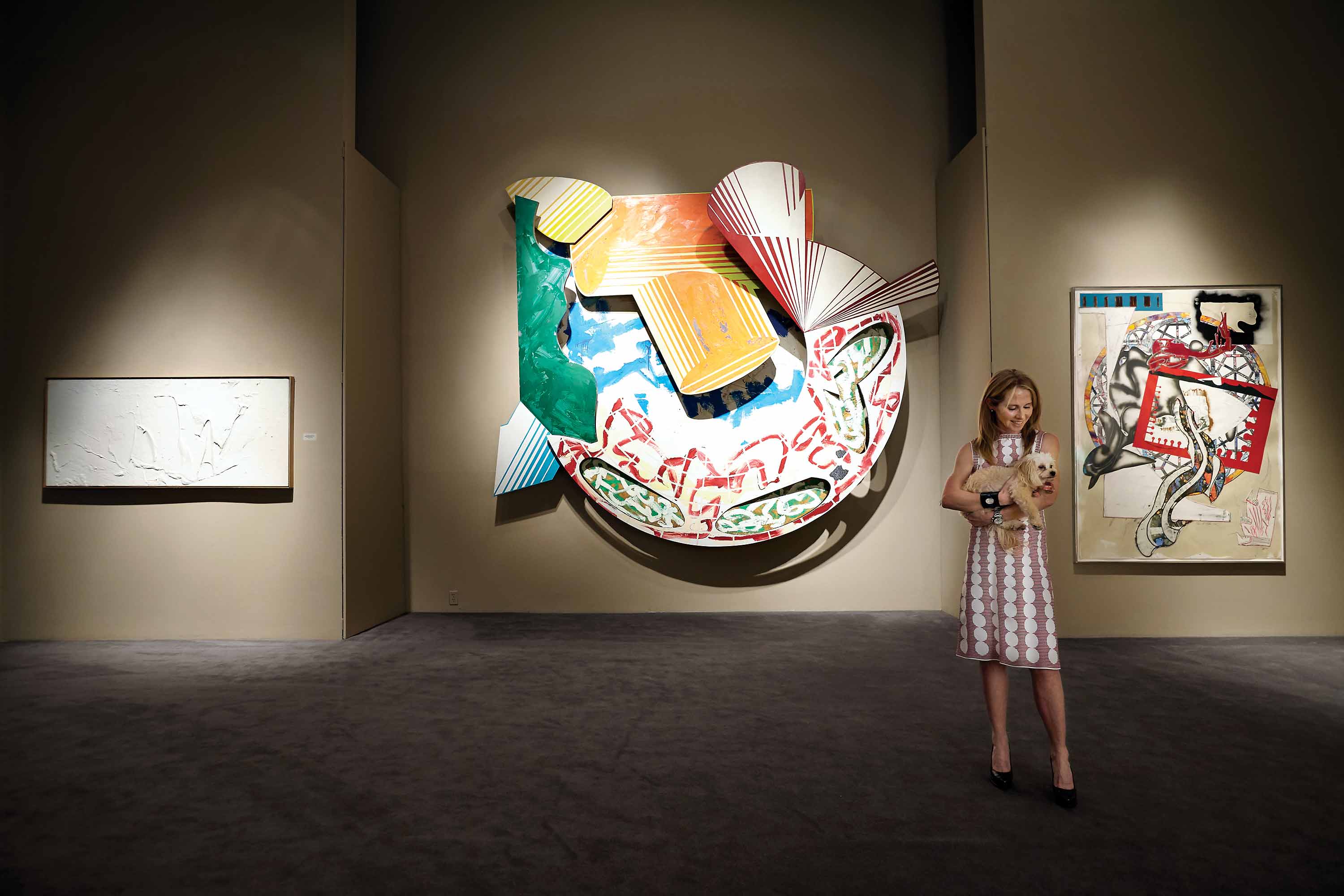

Martha has a gift for putting everyone at ease; smart, decisive and down-to-earth, she shares her father’s love for canines. During our photo shoot, Huggy Bear, a poodle/ Maltese mix rested in her arms. Martha began at the gallery at age 13, working summers during college.

“I answered the phones with Jeanette [Pliner], so I wouldn’t be around the lifeguards at the pool too much,” she says, “and I returned full-time when I was 27.”

15 QUESTIONS FOR MR. LONG

PaperCity: Take us back to the beginning.

Long: I lived in Missouri until I was about 12, then Austin. I was in law school there and got called up in the Air Force ROTC for the Korean War. I was shipped to French Morocco. I was on my way to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and stopped by Washington, D.C. That’s when I went to the Corcoran and saw their American art. During that trip, I saw LeRoy Ireland [George Inness expert, author of the artist’s catalogue raisonné].

I got there at one o’clock in the afternoon and left at 11:30 at night. While I was in the Air Force, I corresponded with LeRoy, and he encouraged me to go into the art business. So when I came back, I didn’t pursue my legal studies very seriously. I opened a gallery at 2825 Rio Grande in Austin, where I had rented a house. I lived in that house with my wife and young son, Beau. That was the first gallery. It was 1953.

LeRoy sent a whole group of paintings down there, which I bought. Good paintings. George Innesses. Ernest Lawsons. Theodore Robinsons, Asher B. Durands. I had this gallery that no one came into until I went out and got them. I learned a lot.

There was a guy who owned a car wash and, as part of his marketing campaign, mailed new residents a coupon for a free wash. He sent one to George Inness and one to R.A. Blakelock. I opened my gallery in Houston in 1957 in Highland Village. What was it like selling American impressionists in Houston, Texas, in the 1950s? Well, you didn’t have a lot of company. I don’t think it was a great deal different than it was in New York. That is, they weren’t selling there either. We had some pretty good paintings.

Several years ago, I bought a Hassam at auction for a client that I originally sold some time in the early ’60s. At the time, Hassams were the most expensive: $7,500. Some of them now, such as the flag paintings, are about $10 million.

I liked American paintings. I really had a very strong conviction that they were underpriced for what they were, and they were extremely good. We are the only people outside of New York that focused on American art. Eventually, there were a number of people in Houston who collected very good paintings.

Art love at first sight.

Long: It started with a man. I married his daughter. His name was Ernest Closuit. He was an art collector, and he lived in Fort Worth. I would be up there, and I would see him unpacking what he bought when he went to New York, and I became interested. And he knew LeRoy Ireland, too. LeRoy was working on a catalog, and everybody that knew anything about art knew who LeRoy Ireland was … I knew I was going to be an art dealer. But I didn’t quit selling fans.

I sold fans and air conditioners for years; my father got me a piece of the territory from Curtis Mathes so I could pay for my first wife.

On selling John Singer Sargent.

Long: I was just right in the middle of everything. And it was a wonderful time for me. Other people came and become great collectors of American paintings and formed important collections. Houston began to really develop. You can see it on the walls down at the museum. We sold, I think, 43 Sargents. Pretty impressive figure.

Best advice you ever got.

Long: On one of my trips to New York, Jay Rousuck, vice president, and mentor, at Wildenstein, said, “You ought to have a bar in your gallery for young men to stop by in the afternoon on their way home” — which I did. It was very successful, although on some days too successful. People began to congregate. It was a really great group of people.

And on the next trip, he said, “You show sporting painters, don’t you, Meredith?” And I said, “Oh no, no, no, we don’t do that. That’s not our kind of thing. That’s popcorn art.”

He said, “Meredith, let me remind you of something. The Mellons, the Rockefellers, they’re all sportsmen. You need to show things that they’re interested in.”

Well, I thought about it on the airplane on the way home and thought, ‘Maybe we better do that.’ Around that time, Jack Cowan showed up one afternoon. I guess I was sort of in a hurry. I told him, “Well, Jack, I might want to see you later, but not right now.”

That weekend happened to be when I was invited to go goose shooting with David Wintermannat his fabulous estate. Wintermann said, “Have you seen the new book that Schlumberger put out on Cowan prints?” I got to thinking about it. I called him back, and I said, “Jack, I’d like to look at those works again.” He said, “Okay, Meredith but the other day you weren’t interested.” I said, “Well, I learned a lot in a week.”

Jack was my first artist in that field — it opened all kinds of doors for me. People who are ranchers and landowners and so forth are interested and like to look at paintings — good paintings, good watercolors — showing all kinds of shooting in Texas. I took Cowan, Herb Booth, and Al Barnes to New York. Only thing is, I had a partner in New York [in the gallery Davis and Long], Roy Davis; he also represented an important Eastern sporting painter. And he didn’t want Jack Cowan.

I said, “Well, this is my place, and he’s going be there.” I wanted Jack to get some nice national recognition. By the time we parted at his death, Jack had gone from a tough $850 price to $35,000 to $40,000 with regularity.

Big break.

Long: The first big painting I sold in Houston was to Mrs. Goodrich. We can look it up: a French Impressionist picture from a Kansas City dealer [Long was dealing French painting during the gallery’s earliest days]. I sold it for $37,500,and I thought, ‘My god, what a deal.’ That’s more than my house cost. I lived right over here on Locke Lane.

You met Cornelia at the original Houston gallery in Highland Village …

Long: That’s right. She was serious and quiet. I didn’t really know who she was. But she wanted to buy some art. I interested her in some paintings, one of which hangs on our wall at home, a Sargent. She was on about three major committees in the museum at this point. She should be. She is just very good at what she does. She really works at it like a job … Cornelia and I spend a great deal of time together, and with out children, and now grandchildren and a great grandchild.

Family is very important. I also spend time with my sons and sons-in-law, taking them hunting.

On giving back.

Long: You just have to become a part of the community. That’s what I did. I supported activities, and I underwrote what I could and did what I could to help make it work … With the Alley Theatre, Patty Hubbard got me in that … Sure enough, I got to know a few people, and I got them to step it up, and we ended up changing directors, of course, as you know — not without some commotion — and now we have Greg Boyd.

He’s world-class … I was a chairman of the Texas Heart Institute for 25 years, and it’s a remarkable organization. It’s just fantastic. I went in there one day to get checked out. I was going to New York to see some paintings to sell, and a doctor that I knew said, “Wait a minute, Meredith, you’re not going anywhere now. You know that [aneurysm in the aorta] could burst. That could kill you.”

So then we walked across the room, and I said, “Who is going to do this damn operation?” He said, “He’s standing right there. Denton Cooley.” And he did. That was about 20 years ago. I’ve had a slice of everything that the Heart Institute does.

On dogs, hunting, fishing, and outdoor life.

Long: When I got to Houston, shooting was a big thing, and if you wanted to get acquainted, you better get your shotgun out and get to know these people. Which were all great guys. And I got leases, dogs, cars, wagons, everything it takes. I got five of every kind of jacket. Martha will tell you; she grew up in the middle of it.

I bought my first English shotgun, then I bought my second, then I bought my third, then I bought my fourth, but it’s been a great ride. It’s been something I’ve enjoyed; it’s a very precious thing to me.

Why sporting art matters.

Long: Sporting paintings are depicting a way of life that has disappeared in the state of Texas. It’ll be history in another 50 years. You see more and more houses, and this means less and less game. I used to be able to stand in my backyard here, one block over, and hear the geese at night. No more geese, no more anything.

The whole thing has begun to change, and these guys who are such good artists, they’re documentarians of that way of life. Cowan, Booth, and Barnes. They knew it, and they loved it, and they documented it.

On collecting.

Long: I had to be very careful that I was not exceeding my clients. You let the clients pick first. Always. You nearly always sell the best things you’ve got. I don’t have the best 19th-century American paintings because I sold them to Bill Kilroy.

Art-world relationships.

Long: Fayez Sarofim was one of my first guys. He and I were about the same age and sort of at the same stage. Fayez’s firm hadn’t gotten to be what it is today, and I hadn’t gotten to be what we are. We became friends, and we still are. I sold him a Childe Hassum. Fayez has a very distinct personality, and I guess I do too.

I’ve had an account with him for more years than you can think. He started his business, Sarofim & Company, and he’s done a magnificent job, a great job. He made a contribution. He became a great collector of American art. Sarofim is the only businessman of magnate status who has important paintings in his office.

Alfred Glassell was a person unto himself. He was a great friend to me. Mr. Glassell wasn’t afraid of art, and we went hunting or birding every week after he bought the ranch. We just had a great time, and a lot of that still goes on in Houston. But it’s not the same as it used to be.

Helen Frankenthaler was considered a very formidable woman. But she was never that way with me, I’ll tell you that. She gave me one of the last prints that she did, and somebody said, “I’m sure glad she’s married, because I don’t think you would last long.” Helen was a really nice woman, and she in a way mothered and shepherded those Color Field artists: Jules Olitski, Ken Noland, Stanley Boxer, Dan Christensen, Darryl Hughto. It was a whole school.

David Wintermann was an emperor of Eagle Lake, and he had all these rice fields. And Pete Bushman, who I got to know, he was an attorney at Vincent & Elkins, and he introduced me to Mr. Wintermann. Mr. Wintermann and I got along fine, and so I got plenty of invitations to go shooting with him.

Boldest moves.

Long: I was audacious enough to start a lecture series, and it was about once a month. Mrs. Blaffer came. I was at Highland Village at the time. I had never seen such a line of cars. Full of Cadillacs. They would all come here to see a whippersnapper talk about some art. And I took a show of three painters from America to Paris in 1959: Jack Boynton, Paul Maxwell, Dan Wingren. The guy from the museum in Paris came to see the show. I don’t know what possessed me to think I could take over the Paris market.

The whole thing began to mushroom, and at one point, I had three galleries in New York. Yeah, and I did go to L.A. for a short time — one year.

On contemporary art.

Long: When I started, I thought that I wouldn’t handle anything but 19th-and 20th-century American paintings. Then I overheard someone asking one of Texas’ best artists, Dan Wingren, “Does Meredith handle your work?” And Wingren said,

“No, you got to be dead to be in his gallery.” That made me think, ‘You know that’s really not right. I ought to try to do something for these people too.’ And that’s why we’ve given that award every year to the museum school [the Glassell School of Art], because I thought the museum was a good organization, good artists come out of it, and there ought to be a prize for the outstanding student, so we’ve been giving a prize [the $10,000 Meredith J. Long Core Program Award].

Favorite museum.

Long: I think a great deal of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. I’m very proud of it. It’s a really great museum, and it’s got a good new director, and the director has made a contribution … Gary Tinterow is just really good. He’s a scholar. He can touch all bases. He trained in a good school. But he can also give us the other side of the art world.

He’s having these European shows. I did mutter under my breath, ‘I hope we don’t forget to go back to American things.’ We’re going to leave our collection to the museum. We set out to do it; when we started collecting we collected for final delivery to the MFAH. We showed [Gary Tinterow] what’s on the list, and he said, yeah, he’d like to have it. And along the way we’ve given other things …

Best part of the ride.

Long: I had a wonderful audience. The patriarchs of Houston were here in this gallery. If they weren’t, their sons were here at the bar at 5 o’clock; it was a big part of it. When these artists came, they’d come in groups of five or six. I had a ball. It was exactly what I wanted to see happen. It was just fabulous, and I saw the world from their point of view, and that had a lot to do with my reactions about things.

Another one of the things that I think is important: People that are interested in art and paintings and so forth are usually nice, easy people to get along with.

Artists to single out.

Long: Inness in a sense is a favorite — a bit of a talisman for me. He is a great, great American painter, more complex than some of the American Impressionists. And I think Mr. Noland is a great American artist; if you compare him to other contemporary art, and what that costs, I feel like Noland and Frankenthaler are undervalued.

The places you go.

Long: If I’m not at the gallery, I’m probably figuring out when I’m going to go to the gallery. And fly-fishing up there in Colorado and shooting birds down here at the ranch.

The next generation.

Long: Martha is my great surprise and help. I’m serious. I came back one day from somewhere, I don’t know where, and I had a sudden inkling of, ‘Whoa, Martha is growing up, and she’s going to the bar.’