Move Over Pollock, It’s Time to Embrace an Overlooked Woman Artist — The Menil Boldly Paints Janet Sobel as a Hidden Influence and Power of Her Own

This Ukrainian-American Painter Fought Through Horrific Adversity and Made Her Mark Before Jackson Pollock

BY Ericka Schiche //Janet Sobel paints in her apartment in Brooklyn, around 1944. (Courtesy of Gary Snyder Fine Art, NY)

For decades, works by women artists have been relegated to the margins of art history. One such artist is Janet Sobel, an innovative Ukrainian-American painter who pioneered the use of all-over and drip painting techniques. Although her work pre-dated — and even influenced — the art of action painter Jackson Pollock, she remains largely unknown.

The Menil Collection’s Janet Sobel: All-Over exhibit reintroduces and restores the legacy of this important artist. The first major museum retrospective of her work, curated by Natalie Dupêcher, is on exhibit in Houston through this Sunday, August 11.

Her Father’s Murder and Emigrating to America

Sobel was born Jennie Olechovsky to a Jewish family in Ukraine near Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipro). Her life story was both inspiring and defined by perseverance.

“She grew up in a shtetl,” Leonard “Len” Sobel, her grandson who lives in Houston, tells PaperCity. “There were always lots and lots of pogroms. After the 1905 revolution, there were horrible pogroms and anti-Semitism.”

During one massacre, Sobel’s father Baruch Olechovsky was murdered. Sobel witnessed the incident while hiding behind a stove with her mother. It was a harrowing, devastating moment that changed the Olechovsky family’s lives forever.

As conditions worsened in Ukraine, the family wandered nearly 300 miles between Kyiv and Odessa on foot. They later emigrated to the United States in 1908 and settled in Brooklyn when Sobel was 15 years old. She would not take up painting until 1937, well into her own motherhood.

The Menil Revisits Janet Sobel

The Menil Collection exhibition, which includes ephemera and more than 30 artworks, reestablishes Sobel as an important foundational 20th-century artist.

Houston-based art historian Sandra Zalman’s essay describes Sobel as “part folk artist, Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist, but critics found it easiest to call her a ‘primitive.’ ”

She also asserted Sobel “occupied a circumscribed space where she was at once in dialogue with the avant-garde but could not become part of it.”

Many of the paintings and crayon drawings featured in the Menil reflect the experimental nature of Sobel’s art practice. Dupêcher, associate curator of modern art at The Menil Collection, views the show as restorative. Part of the effort to reintroduce Sobel, in Dupêcher’s words, includes “reinserting her into the narrative, putting her back to where she originally was.”

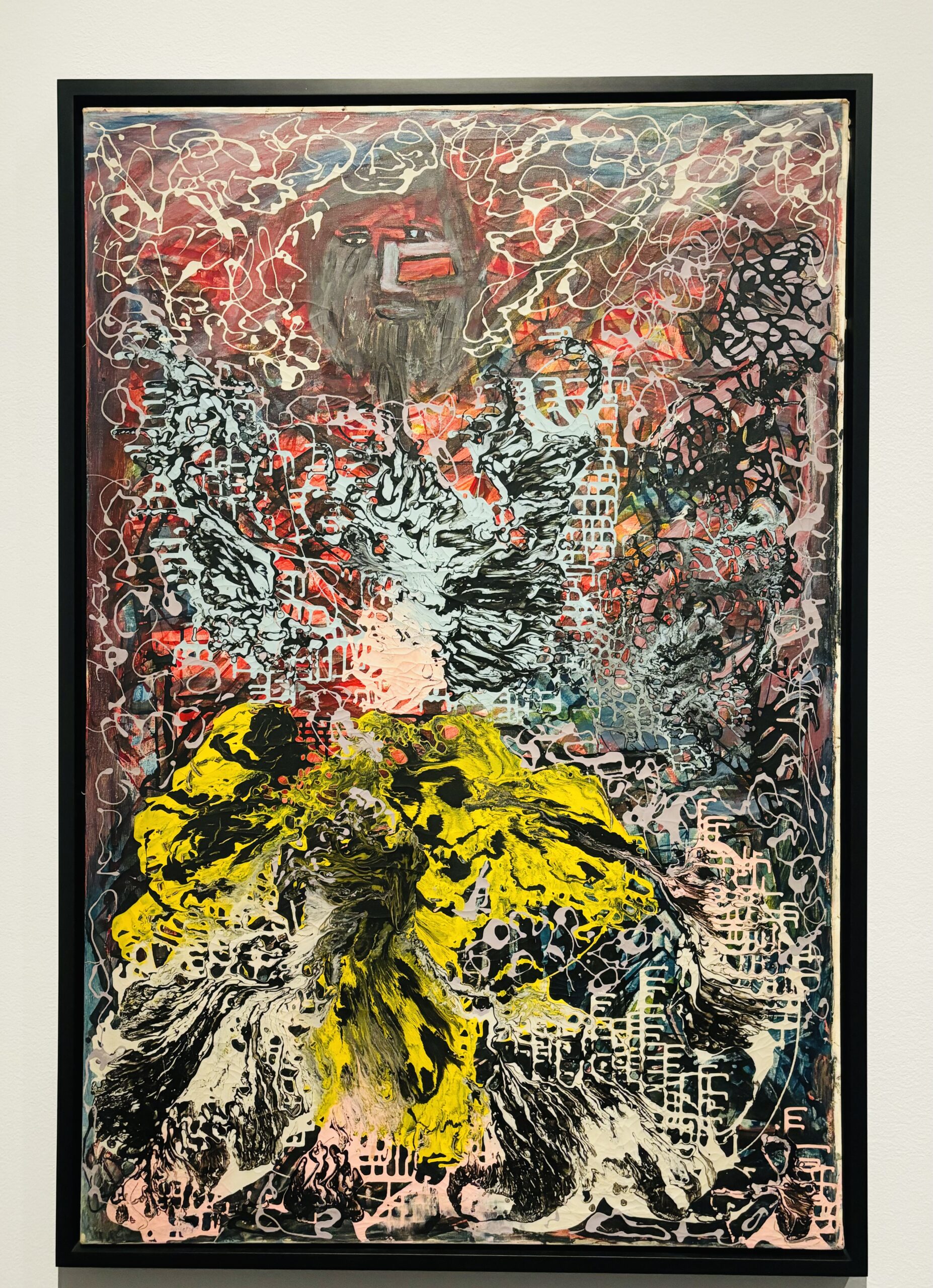

Noteworthy works featured in the exhibit include Hiroshima (1948), Disappointment (1943), Milky Way (1945), Heavenly Sympathy (1947) and Heavenly Quarrel (1942). Although not included in the exhibit, Sobel also created war-themed paintings with titles like Nagasaki, Bomb for Korea and Hitler’s Hell.

“The Milky Way was her absolute masterpiece in many ways, but there are others,” Len says.

In Sobel’s unique and self-contained artistic world, haunting figures appear in both her drawings and paintings. Some of these figures were inspired by her relatives and friends.

“Heavenly Sympathy — I love that painting,” Len says. “In an abstract fashion, it has pictures of people in it.”

Sobel used various types of paint throughout her career, such as oil, gouache, enamel and puff paint. She also used materials including ink, sand, glass, paper, canvas and crayon. She even occasionally designed jewelry made with faux pearls, rhinestones, plastic or glass for the Sobel Brothers family business.

In the 1940s, Sobel developed an allergy to the oil paint she was using. While she did not completely abandon painting, she also began drawing with crayon.

From Pollock to Guggenheim: Janet Sobel’s Champions

Supporters of Sobel’s work ranged from art dealer Sidney Janis to philosopher John Dewey, as well as Surrealists such as André Breton and Dadaism icon Max Ernst. Among her most significant champions was gallerist and collector Peggy Guggenheim, who owned the Art of This Century gallery in New York City during the 1940s.

“Sobel was really a peer of these artists,” Dupêcher notes. “She corresponded with Marc Chagall and Mark Rothko. She exhibited alongside Jackson Pollock. In Peggy Guggenheim’s The Women show, she exhibited alongside Leonora Carrington and Lee Krasner.”

In 1951, Pollock even admitted that Sobel influenced his painting technique, highlighting her impact on significant figures of the time. This acknowledgement raises questions about how the broader recognition of her influence could have altered art history.

In addition to the group exhibition, Guggenheim gave Sobel a solo show at Art of This Century in 1946. But the very next year, in 1947, Dupêcher described a “twin departure.” Sobel moved her family to Plainfield, New Jersey, and Guggenheim moved to Venice, Italy.

But a few years before both women left New York, Dupêcher recalls how Guggenheim wrote to another gallerist, saying, “Put Janet Sobel on your list. She is the best woman painter by far.”

The “Janet Sobel: All Over” exhibit is on view through this Sunday, August 11 at The Menil Collection. Get more information here.