Dallas’ Great Polo Comeback: Fading Sport Finds New Life in the City That Used to be the Mecca of it All

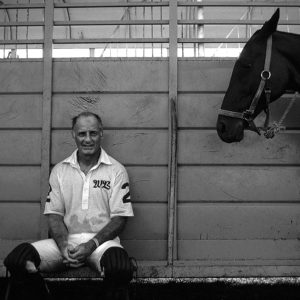

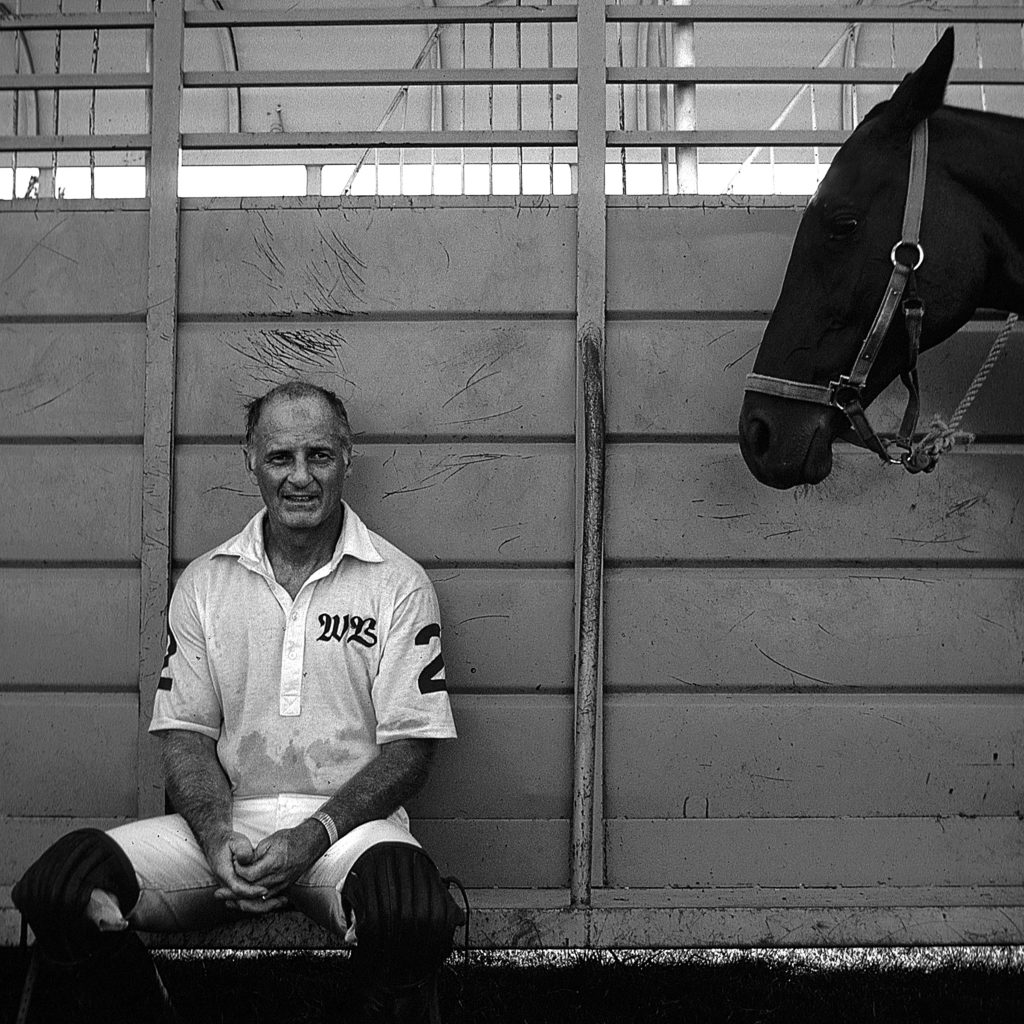

BY Rebecca Sherman // 06.28.18The late Norman Brinker circa 1980, at Willow Bend Polo and Hunt Club.

In 1976, a story in The Wall Street Journal proclaimed polo as America’s new booming spectator sport. Polo centers popped up across the country and throughout Texas — but nowhere was polo a bigger deal than in Dallas.

Willow Bend Polo and Hunt Club, which opened in 1973 on the site of a former turkey farm, was the epicenter of Lone Star polo fever, drawing hundreds — and later thousands — to its Sunday spring and summer matches. If it wasn’t a scene from Pretty Woman, it was close.

Matches were elegant affairs, with a wealthy contingency in breezy dresses and pressed khaki trousers, sipping cocktails from private boxes. Regular folks dressed in shorts or jeans and boots crowded the stands. When actor and polo player Tommy Lee Jones wasn’t on horseback, galloping across the manicured Bermuda-grass field during a match, fans were hoping to get a glimpse of him in the VIP box.

Restaurateur Norman Brinker, who founded Willow Bend with real estate developer Danny Robinowitz, was an Olympic equestrian and a charismatic force behind popularizing the sport. From Highland Park, the club was an easy 20-minute dash up the North Texas Tollway until it fizzled out at country road FM 544, now Plano’s heavily congested Park Road.

It offered amenities the sporting set was used to: tennis courts, a swimming pool, stables, and a clubhouse with a full-service restaurant and bar. Most significantly, it was a serious equestrian center with hunter-jumper facilities, five polo fields, polo and riding instruction, and a multilevel coaching program to develop new players. Brinker, who became chairman of the United States Polo Association, recruited high-goal players from around the world, and hosted prestigious tournaments at the club, including the U.S. Polo Association’s Silver Cup.

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, Willow Bend was one of the top polo clubs in the country, says Charles Smith, who started playing there in 1973 and later became a coach. He’s now a member of the U.S. Polo Association Hall of Fame.

“Norman’s involvement was key to all that success,” Smith says. “But polo clubs have a history of coming and going, and it rests on whether they have a strong person behind them.”

In 1993, Brinker was seriously injured during a match, and permanently sidelined. Willow Bend — and local polo in general — lost much of its momentum. By 1996, Willow Bend had shuttered, and its five polo fields — each the size of nine NFL football fields — had been turned into a housing development.

Former Willow Bend members established the Las Colinas Polo Club on land managed by the city of Irving for equestrian use, and polo continued as a spectator sport there until 2011, when the land was sold. Local polo has since been relegated to mostly invitation-only matches on private land. An hour north of Dallas in Little Elm, there’s a cluster of 10 polo farms, including a large spread owned by billionaire and polo enthusiast John Muse, chairman of Lucchese Bootmaker, and sponsor of the top-ranked Lucchese polo team.

Robert Payne, Jr., a pro whose father was a partner at Willow Bend with Brinker, offers lessons and matches in Little Elm under the Willow Bend Polo and Hunt Club name. Polo clubs worldwide have struggled to stay afloat as fewer young players enter the sport, and the numbers of patróns, or sponsors, footing the bill for players and teams, dwindles.

In 2017, the USPA registered 5,000 polo players nationwide, and 597 throughout the southwest. In Dallas, only about 80 people play polo.

“And that includes anyone with a horse and mallet knocking the ball around a field,” says USPA member Vincent Meyer, who has been supplying equipment to players for 42 years through his Dallas-based company, Texas Polo. Several factors play into those numbers, and chief among them is the cost. Getting started can set you back a minimum of $100,000 for tack, a trailer, and four horses.

Accessibility is another factor, with most local polo facilities located far north of town, where development has migrated and the traffic-snarled journey to play, take lessons, or watch a game can

take hours.

A New Polo Mecca

Longtime polo pro Ignacio “Nacho” Estrada is bucking all those challenges at his newly opened Legends Horse Ranch, 33 miles southeast of downtown Dallas in Kaufman. Estrada bought the land because of its proximity to downtown and the Park Cities, where most of his customers live and work. The trip along US 175 takes about 35 minutes, and a bit longer at rush hour, notes Estrada, who commutes each day from Highland Park, where he lives with his wife Kimberly Pearcy, the ranch’s manager.

“The location is important,” he says. “People can jump in their cars after work and be here really quickly.”

The 34-acre facility is a full-service boarding polo and hunter-jumper equestrian center, with 140 stalls, trailer hookups for big events, and a five-room farmhouse for rent. In addition to a grass polo field and outdoor arena, Legends offers a covered arena and race track, amenities not many centers in Texas have.

“We’re multi-use for polo, hunter jumper and Western performance horse shows, dressage, extreme cowboy racing, and boarding and overnight stays,” says Estrada, who has a varied background in horsemanship.

Born in Mexico City, he started riding at age six and later became a charro — or cowboy. At 16, he became a hunter-jumper competitor, and taught for 20 years in Mexico City. Estrada picked up polo 15 years ago when he moved to Cancun, where he started the Yucatan Peninsula’s first polo school and club. He moved to Dallas three years ago when he married, playing polo at private farms such as Margaritaville Polo Club in Burleson.

Polo is at the heart of Estrada’s mission at Legends, with a focus on keeping the sport alive by teaching and training new players. “Most clubs focus on people who already know how to play,” he says. “The gap between young and old players is very big around the world. There are almost no kids, and hardly any in their 30s.”

To bridge the gap, Legends hired two instructors, including Gordon Lamb from England, who teaches the basics of riding and jumping. Visiting in-structors also teach clinics in polo and other disciplines of horsemanship.

When students are ready, they graduate to classes taught by Estrada or Wyatt Myr, a pro player and farrier. Myr was a state champion barrel racer growing up in Michigan, and took up polo in college.

“I was hooked immediately on the speed and the fun of polo,” he says.

After college, he spent years competing professionally with teams along the East Coast. He moved to Dallas 10 years ago to help run the Polo Training Foundation, a national organization established in 1967 to promote clinics and interscholastic and collegiate polo. The PTF, which was located on a ranch in Burleson, closed in 2010 during the recession.

“The economy hurt polo, and the last decade has been a rebuilding time across the country,” Myr says. “At Legends, we’re trying to grow new players and teach them how to play safely.”

An Affordable Sport of Kings

One of Estrada’s goals is to make polo affordable by providing everything students need, including trained polo ponies, saddles, tack, chaps, helmets, and other equipment. Lessons are $75 each, or 10 lessons for $500. Next year, group camps for children will be offered.

But the future of the sport may lay in arena polo, a newer, fast-paced version of the ancient outdoor game. Popular around the world for its speed, arena polo is also easier on the pocketbook, since the game can be played with only two horses. In the U.S., interscholastic and intercollegiate polo is played strictly in the arena, and Legends has already hosted the Texas arena league.

The arena is where all Legends’ new students learn to play polo, says Estrada, because it’s much easier in an enclosed environment. Care is taken to ensure students are strong riders before tackling polo on the field.

“Polo is difficult and takes effort and skill,” says Estrada. “Everyone wants to play fast, but if you teach it the right way, and mix good technique with fun, people stay interested.”

The center’s graduated teaching methods and coaching new players has roots in the USPA’s “step-up” program, pioneered by Norman Brinker four decades ago at Willow Bend. Estrada is banking on the idea that Dallas’ love affair with polo that started with Brinker never really went away.

“There’s still the money and the interest here for polo,” Estrada says. “The key is to make it available to people who want to play.”

_md.jpeg)