The Real Jim Crane: Astros’ Mega-Millionaire Owner Tells All On Payrolls, Obama and His Truck Driving Past

BY Chris Baldwin // 02.13.17Houston Astros owner Jim Crane brings intensity and a relentless work ethic to the franchise. (Photo by Alex Bierens de Haan.)

Walking into Minute Maid Park, Jim Crane notices a worker he does not recognize running the cleaning machine. The owner of the Houston Astros stops for a moment and quietly watches the man stop two times to pick up things by hand that the humming machine misses.

Crane, a mega-millionaire with business interests all over America, would seem to have little in common with this time-card employee. But he sees something of himself in the move so he asks the man his name (Raul) and files it away.

“If I see something out of whack, I’ll pick it up or adjust it,” Crane says later in a conference room off his office at the ballpark, not to be confused with his office across town at Crane Worldwide Logistics. “So I want to track Raul and get him some (free Astros) tickets.”

Crane turns to Gene Dias, the Astros vice president of media relations, making sure Dias is writing it down and that Raul will be taken care of. Hours later, Crane is still thinking of the guy running the cleaning machine.

“He was doing that job like it needed to be done,” Crane says. “Saying thank you and giving people a pat on the back is how you keep people loyal and how you keep people motivated. The little guys matter a lot. I still consider myself a little guy.”

James Robert Crane is decidedly not a little guy in Houston — or anywhere else — anymore. The man who moved here in 1982, carting his entire life’s possessions in a small U-Haul trailer, and later needed a $10,000 loan from his sister to start his first company, now travels by private jet and lords over an empire that includes Houston’s Major League Baseball team, his second international shipping company and large swaths of the city’s downtown.

Crane’s Super Vision

This is Houston’s Super Bowl month, but while the big game itself played out at NRG Park, much of the action took place downtown around Discovery Green, blocks from the baseball stadium and a section of the city that Crane is transforming. Downtown Houston stands out as the area most likely to be permanently impacted by the Super Bowl and Crane is doing his part to ensure there is no repeat of the post 2004 Super Bowl development letdown.

Crane committed to opening two new restaurants in 500 Crawford, developer Marvy Finger’s new mid-rise. Potente (the Italian translation for the nickname of Crane’s youngest son James) is a white-table clothed affair that aims to be one of the finest Italian restaurants in America. It quietly opened in the heart of Super Bowl week. Osso & Kristalla (named after Crane’s son Jared and daughter Krystal’s nicknames) is a more casual all-day cafe. This is very personal project for Crane and it shows.

“Hey, I’m right here,” Crane says looking out the window, toward the restaurants, “and I’ll walk over there for lunch. If something’s not right, I’ll see it.”

We’ll spend money. But we won’t spend money we don’t have. People think we’re a big revenue team, but we get no revenue sharing — we’re neutral — and we spend what we make.”

Crane’s sky-high standards — he told Finger he wants Potente to be considered one of the very best restaurants in Houston — may have nudged at least one celebrity chef away from the project. Bryan Caswell of Reef originally was on board, but he backed out in a mutual decision, citing a lack of time. Even when both Caswell and his longtime business partner Bill Floyd were involved in the project (Floyd still is), Crane made the scope of his intensity clear. There are hungry grizzly bears less direct.

“I sat down with them. I said, ‘Guys, I’ve been in some of your restaurants and that’s not what I’m looking at. Can you get to this gear or that gear?’ I wanted to make sure we had all that on the table,” Crane says, shrugging.

Crane replaced Caswell with someone familiar with his demands: executive chef Michael Parker, who runs dining at the ultra-luxe Floridian golf club Crane owns.

When it comes to business, Jim Crane sees only one way to do it right — relentlessly. This is a man whose mother gave him a card — with a bill for $220.85 — when he graduated from college. This after Crane got through four years at the University of Central Missouri on a baseball scholarship and working odd jobs to cover any overrun. Still, his mom wanted her $220.85.

“I go, ‘What are you talking about?’ ” Crane says, chuckling at the memory. “Mom’s like, ‘Well, that’s what I gave you in extra money — while you were in school. By the way, it’s at 4 percent interest.’ Which was her house note interest. I had to pay her back! That taught me the value of the dollar. You tell that to one of my kids, they’d think I was crazy.”

Unlike many of his professional sports franchise owner peers, Crane neither inherited his money or picked it up in one fortuitous dot.com flash (see Mark Cuban). Is it any wonder that this owner runs the Astros as more of a business than a show toy?

While the Astros have waded into baseball’s big money waters under Crane, going on something of a buying spree this winter with the acquisitions of Josh Reddick (four years, $52 million), Carlos Beltran (one year, $16 million) and Brian McCann (the club takes on $23 million of his $34 million New York Yankees contract), hardline principles guiding the team’s finances remain. The Astros have moved toward the middle of Major League Baseball payrolls, but don’t expect them to jump into the fray with the Los Angeles Dodgers, Chicago Cubs or Boston Red Sox of the world anytime soon.

“We’ll spend money,” Crane says. “But we won’t spend money we don’t have. People think we’re a big revenue team, but we get no revenue sharing — we’re neutral — and we spend what we make. We want to win. We want to invest in the team, but we have to be shrewd about how we spend that money.

“(The) L.A. (Dodgers) went bankrupt. The Rangers went bankrupt. We will not go bankrupt.”

To Crane, that would be real failure that stings far beyond any boxscore or World Series drought. This self-made man does not lose money. When Crane made that call to his sister asking for 10 grand to start his own shipping company, Eagle Worldwide, in 1984, she did not know what to expect. By 1995, Eagle had six offices and was doing $120 million annually in sales. “Never had a bank line,” Crane says, proudly. “Just ran it with cash.”

From 1995 to 2000, Eagle racked up almost a billion in sales, soon growing to 400 offices in 100 countries. That $10,000 turned out to be a real version of a Willy Wonka Golden Ticket for Crane’s sister.

Obama’s Friend

Growing up in a suburb of St. Louis as the son of a life insurance salesman and a grocery store clerk, money was always relatively tight. “My dad had a great personality,” Crane says. “People liked to be around him. He was kind of the life of the party. He dressed pretty neat, too. He didn’t have a lot of money, but he dressed up neatly — ironed his own shirts. I can still iron; nobody does that anymore.”

Crane shakes his head. He is not as naturally outgoing as his father. He’s more reserved and measured. People often don’t know what he is thinking when they’re across the negotiating table from him — and he uses this to his advantage.

“When I first started to be around him, you really don’t know,” says Reid Ryan, the Houston Astros president and son of Hall of Fame pitcher Nolan Ryan. “You hear stuff about people, but sometimes you wonder: ‘Is that real? Is that lip service?’ But now that I’ve been here for three years I can tell you Jim has an internal drive to be the best.”

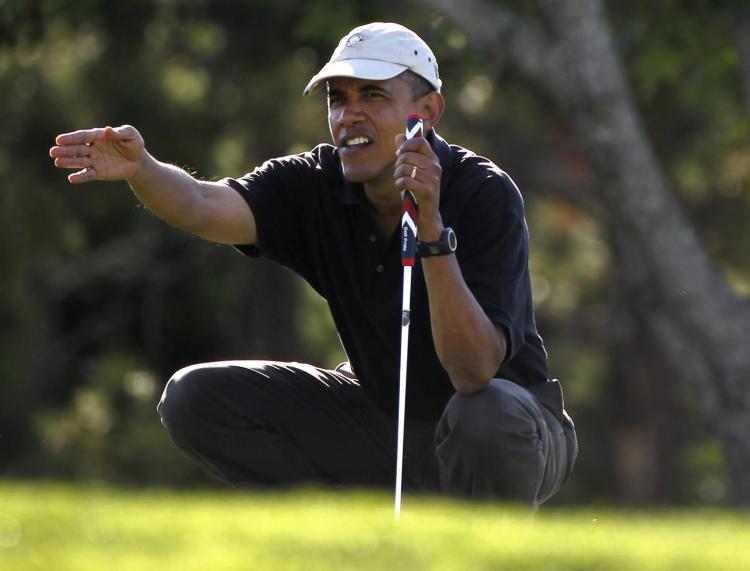

This manifests itself in everything from Crane’s golf game (Golf Digest rated him the No. 1 CEO golfer in the country at one point) to the improvements he’s made at Minute Maid (Reid estimates that Crane’s put more money into the ballpark in the last three years alone than his predecessor Drayton McLane did in all his years owning the team combined) to the shine on the bathroom stalls at his Floridian National Golf Club.

While Crane allows himself the occasional Broadway show (I ran into him at a performance of The Book of Mormon in Manhattan several years ago on a weekend when the Houston Texans were in New York playing the Giants), he mostly keeps a schedule that would exhaust everyone but his most presidential friend.

Crane spent a good amount of time with Barack Obama during his presidency — playing several four-plus hours round of golf with him, getting personally introduced to Cuba president Raul Castro by Obama during Major League Baseball’s historic trip to the island. While Crane insists he’s “neutral” in politics, he clearly built a bond with Obama and sounds like a man who is going to miss the nation’s 44th president.

The business tycoon confesses to being wowed by Obama’s preparation.

“He just knows,” Crane says. “He does his homework, knows how to say something relevant. He’s really easy to be around. He asks you personal questions. He asks about your daughter. He’ll ask, ‘Well, how’d you hit that (golf) shot? What were you thinking about?’ He likes to play. More, he’s competitive. He’ll always want to play for a dollar a nine. Nothing crazy.

“But he’d keep track of it. One guy would say, ‘Oh I got an eight.’ He’d say, ‘No, you had a seven.’ He’d stick around, too. He’d have dinner with us.”

Crane contributed to Obama’s campaigns, but Hillary Clinton never reached out to him in the same way. “I haven’t really met Hillary,” Crane says simply. “Haven’t had a lot of interactions with the Clintons.”

To Crane every detail matters. He has a key to every closet door at the sprawling Minute Maid Park. He can still run a forklift or back up an 18-wheeler truck to a loading dock.

When he first arrived in Houston, he delivered freight at night himself for extra money. “I’d come home from my first job, eat dinner and go back out at 8 or 9 till midnight,” he says. “I always made sure I had enough money to make it work.”

Like the time as a teenager that Crane ran a jackhammer all day and loaded trucks all night, working 16 hour days so he would have enough money to buy a car (a ’69 convertible Camaro).

“If you really sit down and hear his story, it’s an incredible American story and rise,” Astros general manager Jeff Luhnow says. “You almost can’t believe some of the things he went through to become a success. But I always come back to how he treats the guys he went to college with. He really dotes on those guys. Takes them on trips. Enjoys hanging around them.”

Crane does not forget — even if he always seems to be charging ahead. His father died of a heart attack at age 48 when Crane was still in college. His college baseball coach — the one who made sure he did not drop out of school and quit pitching after his dad’s death — died later at age 55. “Good guy, kept a close eye on me,” says Crane, who later donated $1.2 million to his alma mater and had that coach’s name (Robert Tompkins) put on the university’s baseball field.

As a teenager Crane ran a jackhammer all day and loaded trucks all night, working 16 hour days so he would have enough money to buy a car.

With his two biggest mentors gone devastatingly early in life, Jim Crane knows that there is a clock on all this. “I try and stay in shape,” he says. “Instead of drinking two beers, I’ll drink two glasses of water.”

Crane figures he still has more to do. He owns several more plots of land near Minute Maid downtown and is plotting out what to do with them. “I think the neighborhood is going to transform and that’s good for the ballpark,” he says. “This whole area started changing. What really started (the buying spree) is we started to get closed in.

“We basically tried to make investments to control the environment.”

Crane likes to be in control — something a brief stint as a Little League baseball coach years ago surely tested. “The parents get way too involved,” Crane says, laughing at the memory. “One little Hispanic kid, he couldn’t catch. He could throw a little bit, but he couldn’t catch anything.

“You’d throw it to him, it hit him. Well, kid’s mom comes to tell me this kid wants to play first base and she thinks we should give him a chance. I said, ‘Do you have a cellphone and are you going to come to the game?’ She says, ‘Yeah, I’ll be at the game if he plays first.’ I said, ‘I’m going to put him on first, but you’d better have a cellphone because he could catch one in the mouth and we could be going to the hospital.’ ”

Crane throws his palms up. The man who’s renovated 23 Houston city baseball parks so more kids have a place to play isn’t about to sugarcoat things.

This is Jim Crane.

_md.jpg)