My sister, Kate Maher, enveloped in barley. Our grandfather might have laughed when we asked what grain grew in this field. (Photo by Mary Margaret Hansen)

Editor’s Note: Texas artist Mary Margaret Hansen, who’s known for her photo-based work as well as curatorial and public art endeavors, went in search of her family’s roots. The journey led Hansen to cross international borders and to consider an immigrant’s tale of coming to America. This is part three of a series. Check out part one here and part two here.

It’s a cold rainy Sunday morning in mid-September in Saskatchewan, and we three siblings are expectant and shivering. We’ve driven westward from Saskatoon to Biggar, that prairie town where our grandparents stepped off a train in March, 1916, in 40 below zero weather.

A big sign welcomes strangers with these words, “New York is Big, But this is Biggar.” We opt to take photos of ourselves under the sign.

We’ve arrived well before the appointed hour to meet the family who now owns our grandparent’s land. There is time to explore Biggar and eat an early lunch. We discover Prairie Malt Limited, a sizable plant that we surmise is the buyer for unending fields of Saskatchewan barley.

An in-the-moment Google search revealed that the plant is owned by Cargill Malt and is describes Biggar as the place “where some of the best barley in the world is grown within 100 kilometers, and where high quality Canadian malt is processed for domestic and international beer brewing customers.”

(In December, 2018, Cargill sold Prairie Malt Limited to The Boormalt Group, Europe’s second largest malt producer. As I read this announcement, I had a sudden longing for Houston’s own Saint Arnold’s brew, and momentarily speculated on the effects of trade agreements and the inter-connectedness that binds us all.)

Two restaurants on Main Street in Biggar tout the proverbial Canadian Chinese cuisine. I persuade my siblings to lunch at Town and Country Restaurant which advertises “Peking and Cantonese Cuisine, Canadian Food.”

Our waitress is an older white woman. I can see the Chinese cook in the kitchen. The other folks sitting at tables may have come from church and are ordering breakfast dishes. Obsessed as I am with sampling Canadian Chinese Cuisine, I order a Combination Dinner of Chicken Balls, Chicken Fried Rice and Chicken Chop Suey.

Again, the tastes are so different from the Chinese food we savor in Houston at places like FuFu’s. When I break open a fortune cookie, my fortune reads in English and French. I am indeed in Canada, far away from my hometown.

The Land

At last, it’s time to meet Darrell and Brenda Poletz, he whose grandfather Samuel Poletz immigrated from Ukraine in 1913. Samuel’s wife Anne and young daughter followed in the early 1920s, and the growing family settled where a homestead could be had for $10. The Poletz family stayed put in Saskatchewan.

Our Scotch Irish grandparents worked hard as homesteaders for the first eight years of their marriage. Then, lacking funds to carry them through lean years when crops were destroyed by weather and insects, they and their two young sons returned in 1924 to northern New York State and dairy farming. A century later, three of their grandchildren are about to be shown Lewell and Shirley Thompson’s homestead by a family that stayed put.

The Poletz’s are welcoming. They know we’ve come a long way to piece together our grandparents’ story. The five of us sit around their table, finding commonalities as we converse. We speak about grandparents and grandchildren.

We note that rain stopped today’s harvesting and then, at last, we hear the question, “Would we like to see the land?”

We are given knee-high rubber boots to guard against mud and rain, and Darrell drives us on unpaved country roads to Lewell and Shirley’s 640 acres, the legal designation of which is Section 32 in Township 34 in Range 15, west of the 3rd Meridian.

It is 43 degrees with light rain as we approach a forlorn shack of a building. It’s a mess, abandoned, and the thing is, it probably looked shabby 100 years ago when it was a domicile. We sift through memories of old photos.

Our grandmother described the place in her memoir, “The shack was a low, one story affair which had humble beginnings as a one room soddy on a side hill. When its owner married a widow with two children, it was moved and a second room added with its roof slanting down from the ridge pole.

“We grew to know the four rooms intimately… My first impressions were of the windows, how small they were – about 20 inches square … the floor was of narrow strips of fir wood. Had we known enough to oil same, it would have lasted longer and the mop and my fingers would not have picked up so many slivers.

Shirley continues, “Armed with Gilette’s lye, brushes and pails of hot water, Lewell and I began to make the house clean and livable. Liberal application of lye assaulted both wood and our hands… At last the shack smelled clean and would be our own in more than name.”

The chapter devoted to making this prairie home livable ends with this note: “Primitive life was a leveler… I defend not sloth and indolence, but my predecessor, lest the reader underestimate her. She was just another prairie wife struggling to make a home. If this gallant soul failed to reach standards of cleanliness, there were extenuating circumstances. The prairie homemaker fought against great odds.”

John, Kate and I stepped into this tiny structure, walked around it, stood in front of it, glimpsing for the first time, the primitive conditions in which our grandparents performed heroically to become wheat farmers and part of an extended prairie community.

Shirley writes about the first harvest, “The growing season of 1916 was spectacular, so profuse in its bounty that it appeared to flaunt its fecundity. At the time, we did not think this out of the ordinary. It was just what we hoped for… 80 acres of virgin plowing harvested 2,680 bushels of #2 wheat and that 120 acres of stubble, plowed in the spring, produced 4,000 bushels of oats and barley.”

She continues, “Lewell started drawing wheat to Argo, sitting high on the double wagon loaded with sixty bushels of grain. When Lewell returned with the first big check and tried to walk into the kitchen as if nothing unusual had happened, impressionable me wasn’t fooled.”

“Something unusual had happened; the air was sentient and heavy with fruition. Lewell had come home with money and it was ours. Whatever joyful sound I made was as nothing to the dammed-up joy within me.”

Feminism, Way Back When

Again and again, I see a feminist who notices inequities and the habits of men. She writes, “This season it fell to me to go to Biggar and bring home a hired man to stook grain. Trains from the East loaded with seasonal job-hunters discharged their load in successive towns. How I struck a bargain with the squat and thick-set German, I can’t recall.

“However, one thing concerning this hired man made an impression on Lewell and me. He couldn’t conceal his surprise whenever I spoke at the dinner table. His usually set features revealed disdain when Lewell considered my opinions… I don’t believe he knew that his inner censure showed so plainly in his face.”

And, “Here in Biggar were sturdy bewhiskered emigrants from the Old World who, I sensed that day, found a woman’s protest spoken publicly to be a strange thing. Their women folk didn’t question their husband’s opinions or conclusions, let alone dissent publicly. I learned that these women feed their men first; sit at the table only after their satisfied men have risen and need no further waiting on.”

In another chapter, our grandmother writes of the effects of weather: “The destruction of wheat by frost proceeds in measured sequence. The heads of grain do not drop or show the blow at once. And during this interval the man who has sown the grain, watched it grow and planned to pay his debts with it, tries to feel hopeful.

“However, in nature’s own time the green heads turn darker, they shrink and wrinkle A field of waving greenness becomes a desolation of whitish yellow chaff.”

There were many friends and good times in those eight years of prairie life — as the text details. “For a while, we haunted the James’ house. We just never got weary of singing and stopped only when we were hoarse as crows. Part of the fun was accompanying the fine male and female quintet on the James’ piano. We rode eighteen miles round trip to sing, ‘Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes’, and I to play Rachmaninoff’s ‘Prelude in C# Minor.”

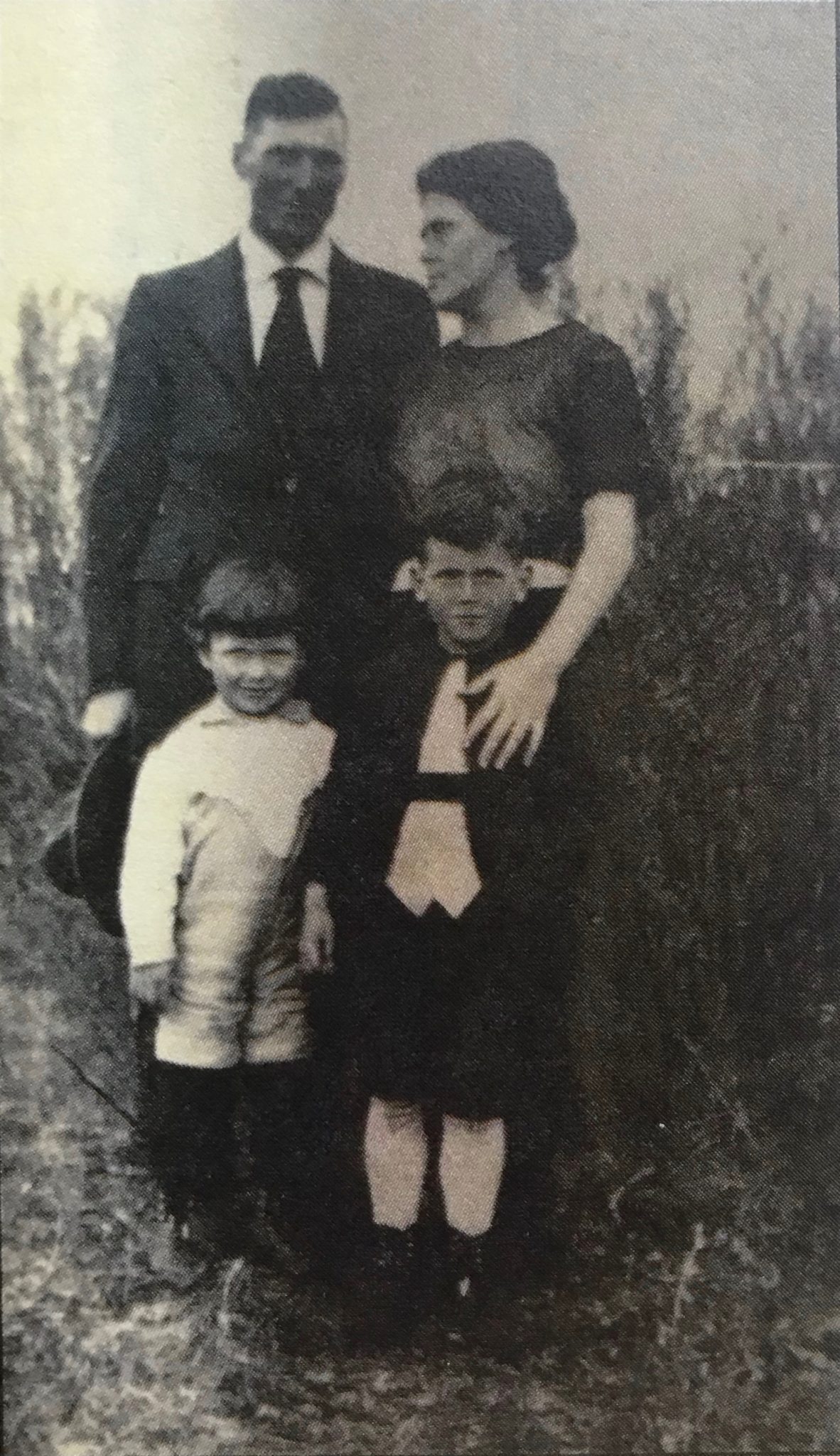

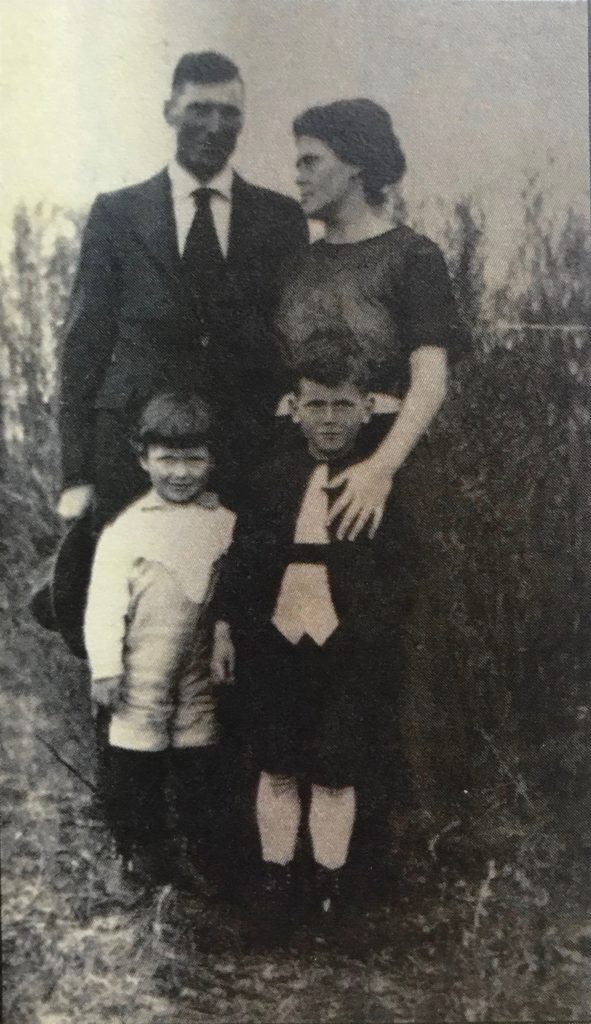

Lewell and Shirley were raising two small sons, the older of which was Dean, our father. “Watching this son of ours grow and react to his environment was seeing the unfolding of the human mind void of suspicion or fear… His daily playmates were the farm fowl and animals. One old Plymouth Rock hen persisted in following him about. He played with little pigs. When the piglets tired and coaxed their mother to lie down, Dean lay down too with his head on the mother pig’s flank.”

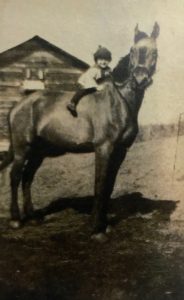

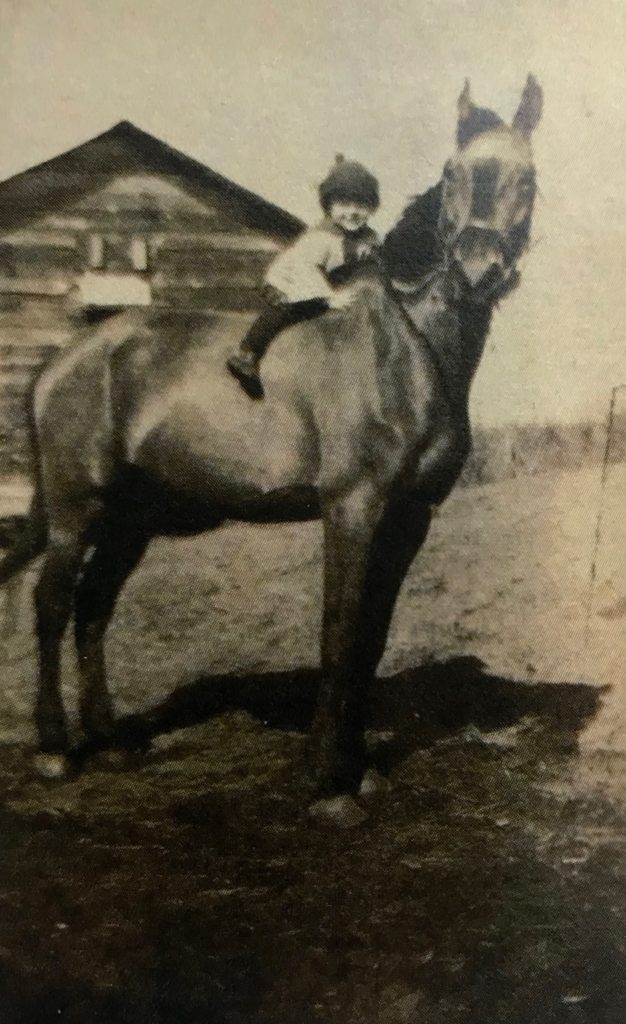

As a 6-year old, our father rode horseback to the country school, “his back ramrod straight, his dinner pail in one hand. Dean’s greatest difficulty was in getting on the horse. If he fell off for any reason, he usually had to walk the rest of the way.”

A Prairie Life

In the final chapter of our grandmother’s memoir, she begins, “The years following the end of the first World War were a disaster for the Canadian wheat farmer. Lewell and I had long since given up on the Wallingford idea of “getting rich quick.”

Our present aim was to pay every cent we owed, with the ultimate objective of pulling up stakes and returning to the East. The 1923 crop gave us the chance we had been hoping for since we had a good harvest and wheat brought $1 a bushel.”

Leaving the Saskatchewan prairie was a heartbreaker. Our grandparent’s auction was well attended, but Shirley writes, “cows, calves, pigs and chicken sold for less than they were worth; the horses fared better, but a favorite sold to a man known for being a poor feeder.”

My grandmother’s mahogany music cabinet with a beveled glass mirror sold for $1. Produce could neither be sold nor given away.

In the end, “The prairie with its vastness, its freedom, its punishment, its immutable laws and its golden-barred sunsets is a part of our life together that no one can take away. It wooed and scorned us by turns. The prairie conjured a vision of execution on a large scale; held out the apple of promise: blue skies fecundity, spring moisture and sun; and then gave drought, or grasshoppers or early frost or dust storms or hail…mocked our temerity in daring to hope…living on the prairie was a glorious adventure.”

On a winter day in 1924, Lewell and Shirley Thompson boarded the Grand Trunk Pacific for the return journey to upper New York State.

John, Kate, and I walked the land on which our paternal grandparents homesteaded. We saw the place where they began to raise two sons and make life-long friends, but found they could not hold on to the prairie’s promise.

We thanked the Poletz’s for their kindness and hospitality and drove back through rain-soaked golden fields to Saskatoon. John would fly home to Houston as Kate and I drove westward to Alberta, land of dinosaurs and stone hoodoos, hot springs and Lake Louise.

Photos by Mary Margaret Hansen. Vintage photos courtesy the author’s family collection.

Part Four — the conclusion of this road trip odyssey — will run next month on PaperCityMag.com.

_md.jpeg)