The Hidden Sides of Architect Rebel Bruce Goff — a Rare Look at a Generous Genius

Goff Never Shied Away From Controversial Label, He Just Kept Turning Out Unique Masterpiece Houses

BY Robert Morris // 01.26.19Gone but not forgotten: Joe Price House, Shin’en Kan, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 1956.

In this PaperCity exclusive, architect Robert Morris writes about his mentor, the late organic visionary American architect Bruce Goff. The conversation that began their friendship took place in Tyler, Texas, one spring weekend 39 years ago.

The talent who brought them together was another architect of note: It all started with Frank Lloyd Wright. Now, Robert Morris’ words:

One is most fortunate to meet a true genius in one’s lifetime, but even more fortunate to become friends with that genius. Such was my good fortune to become a friend of Bruce Alonzo Goff — architect, artist, composer/musician, craftsman.

Mr. Goff was the most original, extraordinary person I have ever known in my life. As an architect, I have known and worked with many well-known people and projects ranging from Pennzoil Place to the Rothko Chapel, and with individuals including Philip Johnson, Dominique de Menil, John Chase, and Howard Barnstone.

But Mr. Goff was the most extraordinary of them all.

At the age of 22, Mr. Goff designed one of his masterpieces, the Art Deco-style Boston Avenue United Methodist Church, while working with the respected Tulsa architectural firm Rush Endacott Rush. When he was 25, he became a partner in Rush, Endacott & Goff, which closed during the Great Depression.

After serving with the Navy Seabees during World War II, with only a high school diploma, he took a teaching position with the College of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma in 1947. After one semester, he was made the dean of the architecture college, a position he held until 1955.

During his tenure, the architecture program became very well known and garnered students from all over the world. Two of his closest friends were Chicago architect Louis Sullivan and Sullivan’s protégé, Frank Lloyd Wright.

It was following this period that he created some of his most extraordinary work in the modern vernacular he was famed for. Goff defined an approach and style that came to be called, in the post-war period, organic architecture and often included unexpected and novel materials honed from nature or industry that he placed within each structure to lend an air of humanity and root it to place.

Of his homes, the two most well known are Shin’en Kan, designed for Joe Price in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and the Bavinger House, in Norman, Oklahoma — both now gone.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Pavilion for Japanese Art is the most publicly visible. The Hopewell Baptist Church in Edmond, Oklahoma, is one of the must-see buildings on a Goff pilgrimage, and was built in the shape of a teepee using reclaimed steel parts of old Oklahoma oil derricks.

Goff used five-and-dime ashtrays to make the original chandeliers, but all are now missing. (The church is in poor repair, but a local group is trying to raise funds for restoration, via goff-hopewell.com.)

Finally, I’d single out the Redeemer Lutheran Church Educational Building in Bartlesville; I love the arrows and glass cullets in the walls. Goff used cullets, broken chunks from the glass-making process, as well as coal, to enliven many of his buildings’ walls, a striking characteristic from the Bavinger House, in Norman, of the previous decade.

Mr. Goff, I Presume

From 1977 to 1980, I was the producer/director and on-air host of an environmental-issues radio program at the Pacifica network station in Houston. Every spring, I dedicated the month of April to the built environment. For 1979, I decided to focus entirely on architecture and was contemplating what subjects I might incorporate.

While researching the archives of KPFA, the original Pacifica station in Berkeley, I found an excellent program on Frank Lloyd Wright. After listening to the program several times, I decided to use most of it and add some original material to create a month-long broadcast in serial form on the life and work of Mr. Wright.

At this time, I was working in the office of Houston architect Howard Barnstone and met Stephen Fox, an architectural historian who was helping Howard with his book about Houston architect John Staub. During an informal talk with Stephen, I mentioned my idea of a radio broadcast program about Frank Lloyd Wright and that I was thinking of adding some material on Bruce Goff, a lifelong friend of Mr. Wright.

He said Mr. Goff now lived in Tyler, Texas, and gave me his phone number. Soon after talking with Stephen, I called Mr. Goff. Surprisingly, he answered with a warm and delightful “Hello.”

During our conversation, I explained my idea for a radio broadcast about his friend, Frank Lloyd Wright, and he did not hesitate to offer his help. We made plans to spend the 1979 Easter weekend at his studio in Tyler and see where the time took us.

Although I was familiar with some of his work as a result of my architectural courses at Texas Tech University and architectural books that referenced him (usually in relation to Mr. Wright), I really had no idea of his persona. That was about to change in a major way when I arrived at his house and studio on the Saturday morning before Easter.

Tyler, Texas, is not a big town. So, armed with a street map, it was not difficult to navigate a path to his house, which was in the middle of town in an upper-middle-class residential neighborhood. Most of the homes were somewhat modest one-story ranch-style houses, so not knowing what his looked like, I drove right past it.

I stopped and double-checked the street address and drove back to a nice but undistinguished stone-veneer house and parked at the curb. Knowing some of his work, I am not sure what I expected, but I was unsure that this was the correct house, so I checked the address again.

As I sat in my car looking at the front, I noticed thin vertical streamers hanging behind a large window. This feature was unlike anything I had ever seen before as a window treatment, so I decided this must be the house. As I walked up the sidewalk to the front door and rang the doorbell, I began to get nervous.

That quickly dissipated when Mr. Goff opened the door, standing 6-foot-4 tall and wearing a colorful abstract geometric-patterned shirt. With a warm smile and in the same tone I’d heard on the phone, he said, “Hello, you must be Mr. Morris.”

He invited me into his office, which was the front room with the streamers in the window, and it was then I noticed the the window treatment material: standard reel-to-reel audio recording tape! This was the first clue that I was in for a special engagement.

He asked me to take a seat opposite his desk, and as I looked around the room, I noticed there were no images or models of his work. Instead, floor-to-ceiling shelving was filled with record albums and covered with the same vertical recording tape. On the perimeter of his desk were several natural objects such as crystals and seashells.

After the initial period of acquaintance, our conversation flowed easily and naturally, covering a variety of subjects, starting with stories of how he knew Frank Lloyd Wright and their lifelong friendship.

As a young man growing up on a farm outside Tulsa, Mr. Goff would collect natural objects such as sticks, stones, bones, etc. (“natural Legos,” he called them) and make constructions in his room in the attic of his house.

When the ceiling caved in one day, his father apprenticed him, at the age of 12, to the Tulsa architecture firm Rush, Endacott & Rush. The head draftsman, the son of one of the partners, became a mentor to young Bruce and showed him architectural drafting. He realized that Bruce had talent. Sweeping floors stopped, and Goff became a draftsman at 14.

One day in 1918, Goff was given a house to design, and he made drawings unlike anything in the office. The head draftsman stopped by his desk and asked him if he knew the work of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Goff said no, so the draftsman showed him a copy of the 1911 Wasmuth Portfolio, the first international publication of Wright’s work.

Goff was very excited to see that another person was thinking like him and decided to write a letter, simply addressed to Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin, Wisconsin. Weeks passed with no reply, and young Bruce became the brunt of jokes from the other draftsmen.

Then one day, the jokes stopped, as a large box arrived addressed to Mr. Bruce Goff. It was an original edition of the Wasmuth Portfolio in a beautiful silk-covered box with a note inside that read: “Happy to know I have a friend in Tulsa, Oklahoma,” signed Frank Lloyd Wright.

That first day, our conversation progressed from Wright to many other diverse stories and topics. I was so impressed by his knowledge and demeanor that I asked Mr. Goff if we could continue the next day, Easter Sunday, without knowing if he was religious.

He replied, “Of course, I would love to.” So began a course of periodic weekend visits from 1979 through 1981, during which I recorded over 12 hours — a small fraction of our conversations. During one of the visits, he opened his flat files filled with incredible hand-drafted drawings and details of several projects.

On my last visit in 1981, he presented me with a slide show of one of his masterpieces: Shin’en Kan, the house and studio in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, for Joe Price, son of H.C. Price, who built the Price Tower by Frank Lloyd Wright, also in Bartlesville. The one element I remember as extra unusual was the crystal-shaped, colored-glass aquarium in the living room that went through the floor into the ceiling of the master bath below.

Houston’s Goff House

Not long after I moved to Houston in the early 1970s, I encountered the Durst-Gee House during a bicycle tour of the Piney Point area of Memorial while looking for the W.L. Thaxton House designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. I would play a part in saving Thaxton, the only Wright house in Houston, acquired and restored by Allen and Betty Gaw in 1992 (Cite, Spring 1991).

Cruising down a side street, I spotted an unusual house down a small cul-de-sac and decided to go for a look. It was a total surprise — like nothing I had ever seen before. I did not know who’d designed it.

I discovered the house was by Bruce Goff, an architect of whom I first became aware during my university studies in the mid-1960s. Other than a handful of buildings taught in school, I was not versed in what I would discover to be Mr. Goff’s vast oeuvre of more than 500 projects.

I became better acquainted with the Durst-Gee House at the request of Stephen Fox — I was in charge of arranging a tour of it and of the Thaxton-Gaw House for a group of architectural historians meeting in Houston. I met homeowner Julia Gee while I was coordinating the tour, and she told me some wonderful anecdotes about Mr. Goff — or BG, as Julia called him.

She showed me the mosaic glass tile finishes for the home’s columns and around the doorframes that BG crafted in his own hand. I found out later that he did this for almost every project that he designed.

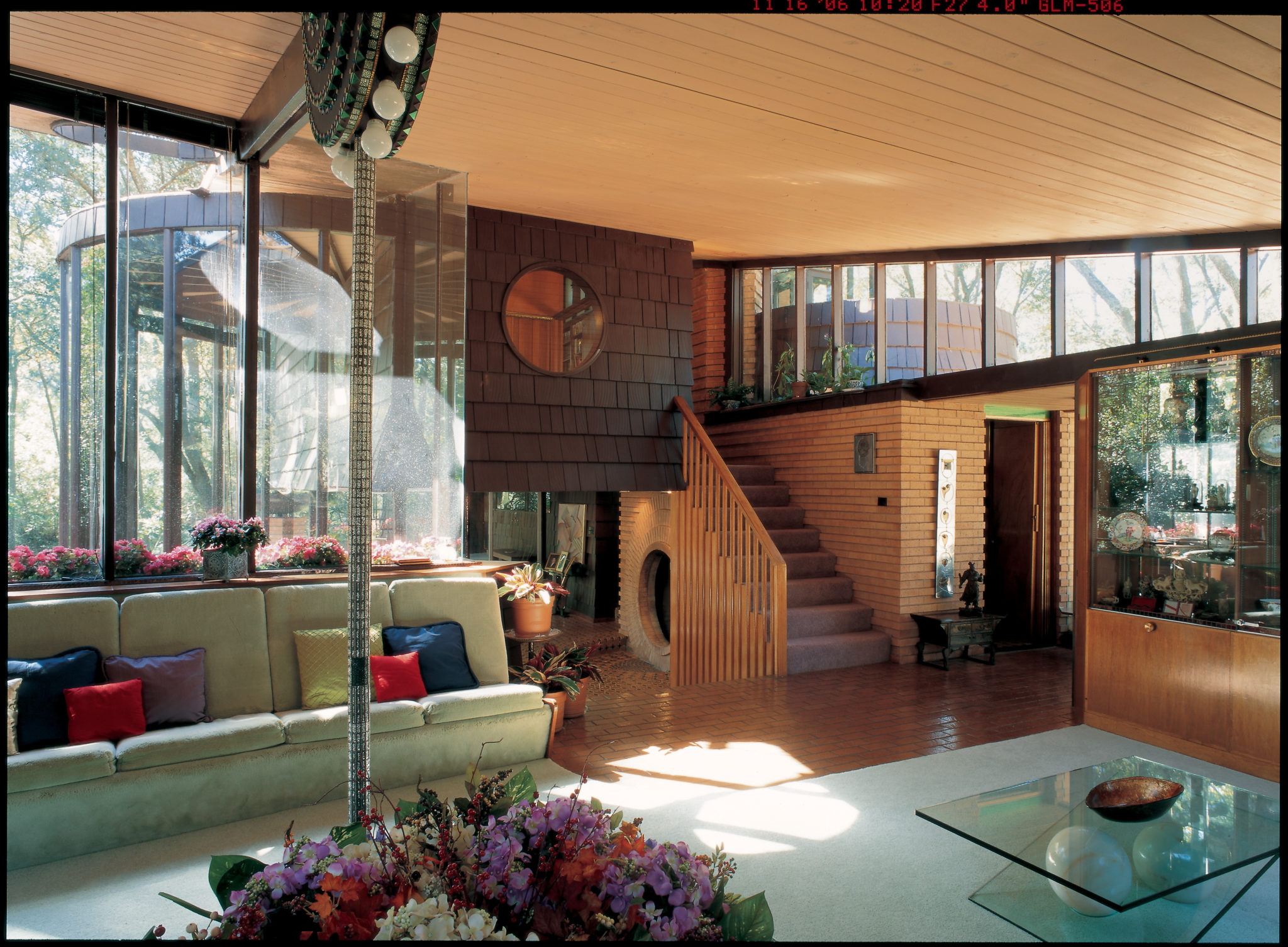

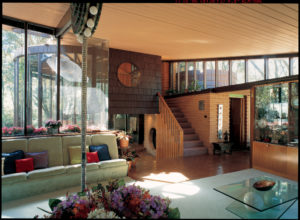

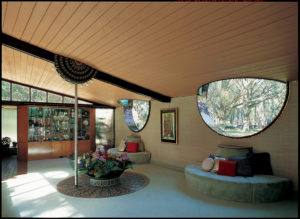

The original owner of 323 Tynebrook Lane was the Robert Gordon Durst family (no relation to New York real-estate heir Robert Alan Durst, who lived in Houston for a while and is currently under arrest in California for murder). The Gee family is the third and current owner. The last addition, designed by Mr. Goff for them, was completed in 1981 and supervised by one of Goff’s students.

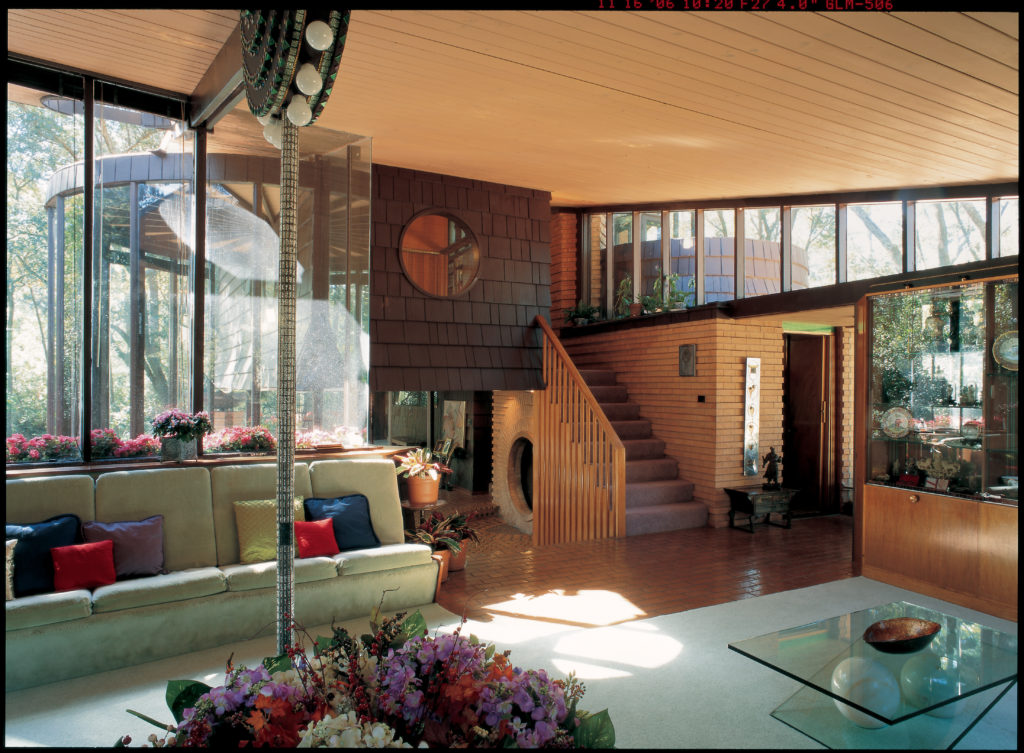

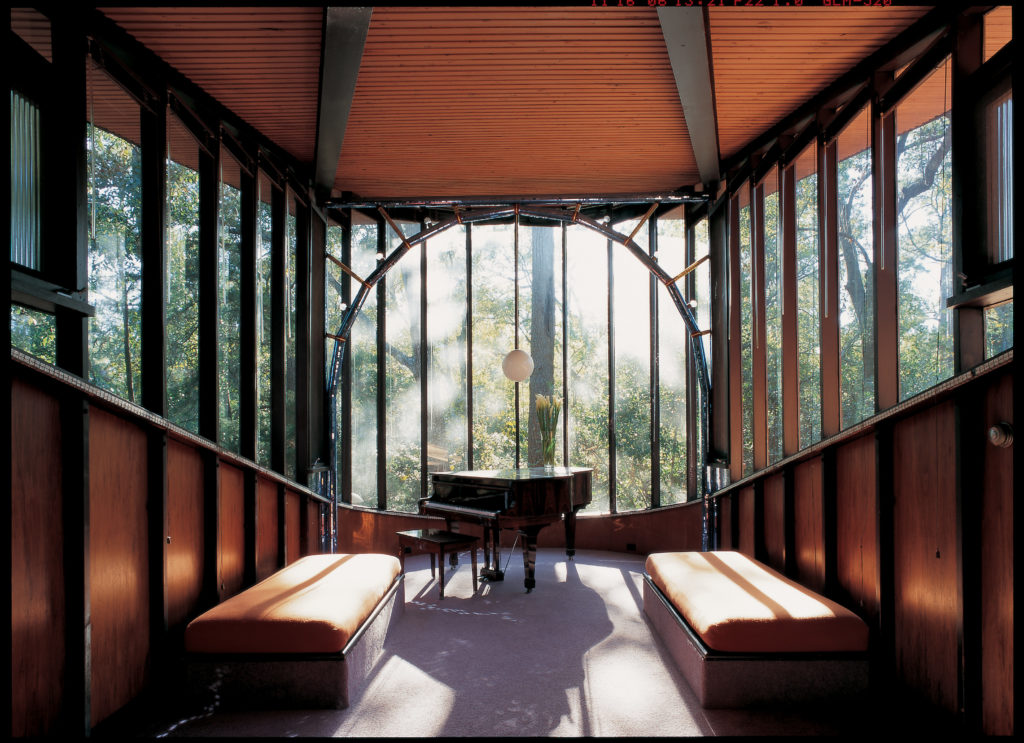

The iconic view of the house is the front wall as seen from Tynebrook Lane. One never forgets the three large round windows that project above the roof and are framed with concentric circles of brick. The circle motif repeats in various exterior and interior elements. The shape of the house changes dramatically as you walk around it. Every side is completely different, featuring varying geometry.

Passing through the compressed front entry, you are immediately thrust into the front living area with its expansive, almost heroic scale. The flat ceiling engages the middle of the three large round windows, but the ceiling is cut into a semicircle around the window to funnel the light into the interior. The living area is open at a right angle to the semicircular dining room flanked by a dramatic circular brick fireplace where Goff personally installed the tile for the hearth.

The Lost Bavinger House

In October 2010, my best friend, the architect Edward Rogers, and I took a road trip to the University of Oklahoma in Norman to attend a weekend symposium, “Bruce Goff: A Creative Mind.” It was co-sponsored by the Friends of Kebyar, an international network that advocates the promotion and preservation of Organic Architecture with an emphasis on the work and teachings of Bruce Alonzo Goff. The nonprofit organization publishes the Friends of Kebyar Journal, to which anyone can subscribe.

There were several speakers, an exhibition of images and models, and a tour of some of Mr. Goff’s significant houses and buildings in the Norman area. The Bavinger House was not on the tour, but a reservation could be made with Mr. Bavinger’s younger son for a private tour, which we did. (Surprisingly, we were the only ones who signed up.)

As we entered the compound, we were met by Bob Bavinger, who lived there, maintained the house, and gave guided tours.

As we approached the hidden entrance, which is achieved by walking around the structure, Ed and I agreed that this was the most amazing work of residential architecture we had ever encountered — and we were yet to go inside! The interior of the house was like being in a dream. Totally unexpected.

The truly original thing was that there were no conventional rooms. The spiraling three-story space was totally open with pods in place of rooms, suspended from the central mast. The pods were shaped like shallow bowls with soft plush carpeting completely covering them.

There was no furniture or beds; one simply sat against the side of the bowl and used a bed roll for sleeping. Each pod had a circular closet, and for privacy, there was a circular curtain around the pod. For safety, there was fabric netting.

My favorite story about the house, which Mr. Goff told me on one of my visits, was how it was built and financed. Eugene and Nancy Bavinger, who both taught art at OU, hand-built the house. As the structure began to rise from the ground, there were floods of visitors who were interested in what was going on.

The curiosity seekers interrupted the construction so much with their myriad of questions that Eugene built a fence around the site, and Nancy sat at the gate and charged each visitor 50 cents to enter. This fee completely paid for the house!

Epilogue

At the end of my first weekend with Mr. Goff, Easter 1979, I thanked him and told him that I would use some of his thoughts for my upcoming Frank Lloyd Wright radio program. I also told him that I would like to return and discuss a radio documentary just about him.

He told me I was welcome anytime, so I made several more visits between 1980 and 1981, recording some of our talks, but mostly listening to his stories — he never repeated a single anecdote in all the hours I spent with him. He was, simply, a wizard.

Unfortunately, Mr. Goff passed away August 4, 1982 before I could complete that project.

Although I never worked with Mr. Goff, I call him my mentor because he is the only creative person who completely shared his mind with me during several weekends of all-day discussions about his life, the visual and performing arts, and architecture.

His philosophy of the creative process and what makes something artistic has remained with me throughout my life. The following are his own words, transcribed from our recorded conversations (published posthumously in Cite, Spring 1983).

Robert Morris: Who were the most influential people in your life?

Bruce Goff: The composer Claude Debussy. I learned more from him than any other creative person. I have managed to find some of his writings and have embraced many of his ideas as my own.

Another man who helped me a great deal in all this was the artist Erté. I use to buy Harper’s Bazaar magazine — not because I was interested in clothes or fashion, but because of the beautiful covers he designed. They were knockouts! In one of Erté’s articles in the magazine, he stated that he was against the mode, meaning fashion, because clothing should express the nature of the individual; clothing should not be a matter of fashion. I felt the same.

Erté asked me, on the occasion of our meeting in 1980, if I had been accused of being Art Deco. I replied, “Yes, I suppose you have been too.” He said it was true, and that it astonished him.

Of course, I was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright in my early years. However, I didn’t want to carry on his work. Wright asked me if I would come to Taliesin, before he established the fellowship, and become his “right-hand man.” I was very busy at the time in Tulsa and was to be a partner in the firm I had apprenticed. I declined the offer then and two other times also.

On the third time, I explained: “Mr. Wright, I regard you highly and know people who have worked with you. You are too big a man for me to be close to, and I need to be away from you in order to keep the right perspective. I hope we can continue to be friends.” Wright was silent for a long time. Then he put his arms around me and gave me a big hug and said: “Bruce, I wish others knew me like you do.” He never asked me to join him again.

Does art ever has a universal appeal?

BG: Anytime we experience a work of art for the first time, the only reason we notice it at all is because it completes a circuit within us and engages our attention.

We may not comprehend it at all, but the important thing is that we notice it.

It’s important to try and refrain from criticizing the work; simply respond to it naturally. In order for a work of art to survive the moment of surprise, the work must contain mystery. It’s nothing anyone can give a formula for. No matter how much you know it, as in knowing nature or people, the mystery is what keeps our interest.

For example, I have about two dozen recorded interpretations of Debussy’s “La Mer,” and every time I listen to any one of them I hear something new. I can never say I know it, any more than I can see the ocean and know it.

You have said that you consider one of your most important achievements to be the “resolution of duality.” What does that mean?

BG: When I was young, the difference between things seemed very clear-cut. Later in life, I began to think there might be a fusion where one part stops and another begins. For instance, when does the color red stop being red before it becomes violet? Any color perception is actually light vibrations. To say red, yellow, and blue are the basis of color is really stupid; light is a sliding scale.

How many things are red that are not at all alike in color? Something beautiful to one person may be ugly to another. This is often the case when we encounter the new, as in Robert Hughes’ The Shock of the New. “The Rite of Spring” by Stravinsky was considered the biggest calamity in music when it first presented to an audience. Of course, it is accepted today as a great work of art.

Your buildings seem musical in their decorative inventions. How has music influenced your work?

BG: Architecture uses the same devices that music does; rhythm, proportion, scale, ornament, harmony, asymmetry. Materials take the place of different musical instruments.

One of the main differences between music and architecture is the use of physical structure. In a building, structure is thought of as a necessity to hold up the building — and thought of, too often, as a separate thing from the form.

In music, the idea of structure is the basis for constructing the form of music. It is much more an integral process than in most architecture.

How should structure be used in architecture?

BG: I don’t think structure is anything to hide or glorify. Some architects make a fetish out of structure, and I know it can be beautiful. A human skeleton can be beautiful, but who wants to shake hands with it!

In the so-called International Style, structure became not so much the function but the appearance of being functional. For instance, Mies’ [van der Rohe] desire to make a floor slab six inches thick throughout to express simplicity was, as he said, “Telling the truth,” because “God is in the details.” Well, the truth wasn’t in the floor slab, that’s for sure.

Now, in so-called Post Modernism, the idea is to make structure that looks like structure that isn’t structure. These architects say, “Why should a column serve a function?” I say, “Why shouldn’t it?” What’s so great about making a column that doesn’t touch the ground or floor, to show it’s only an object?

The idea is refined by not having the column touch the beam, to show it even more. I suppose the next step is not to show it at all. The original Post-Modern architects are called the New York 5. I call them the Subway 7!

Most architects I know who are familiar with your work either don’t like it or don’t understand it …

BG: I’ve been controversial ever since I started. I can’t help it. I’m neither ashamed nor proud of it. That’s just what happened. Still, there’s never been a time when my work was not published some way without my effort to do it. Never once.

There is no mystery force that made me want to be an architect. It was strictly chance. If my father had not apprenticed me when I was 12, I would never have done it on my own, although I did make drawings of buildings.

To me, an architect should always keep growing throughout his life. If he just arrives at a method or formula to produce something, no matter how good it is, it gets old. [Richard] Neutra asked me why I thought I had to change all the time. He asked me why I didn’t take just one of my ideas and perfect it. I replied that I tried to perfect my work each time I did it.

Mies told me he didn’t see any reason why I had to invent a new style every Monday morning. I replied that I didn’t think it should be every Monday morning, but every time I did a new work.

Debussy wrote that he was suspicious of artists who were popular with the public. This is one of my favorite quotes from Debussy: “On that distant day, which I trust is still very far off, when my works shall no longer be the cause of strife, I shall reproach myself bitterly, because that odious hypocrisy which enables one to please all mankind will inevitably have triumphed even on those last works.”

Robert Morris is a registered architect and registered interior designer with a master’s degree in space architecture. He taught from 1999 to 2010 at the University of Houston’s Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture. His corporate career includes work in the firms of Caudill Rowlett Scott (CRS), Johnson/Burgee/S.I. Morris, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), and Howard Barnstone. He currently owns his own eponymous firm, and also is an artist who paints under the name Richard Steele.

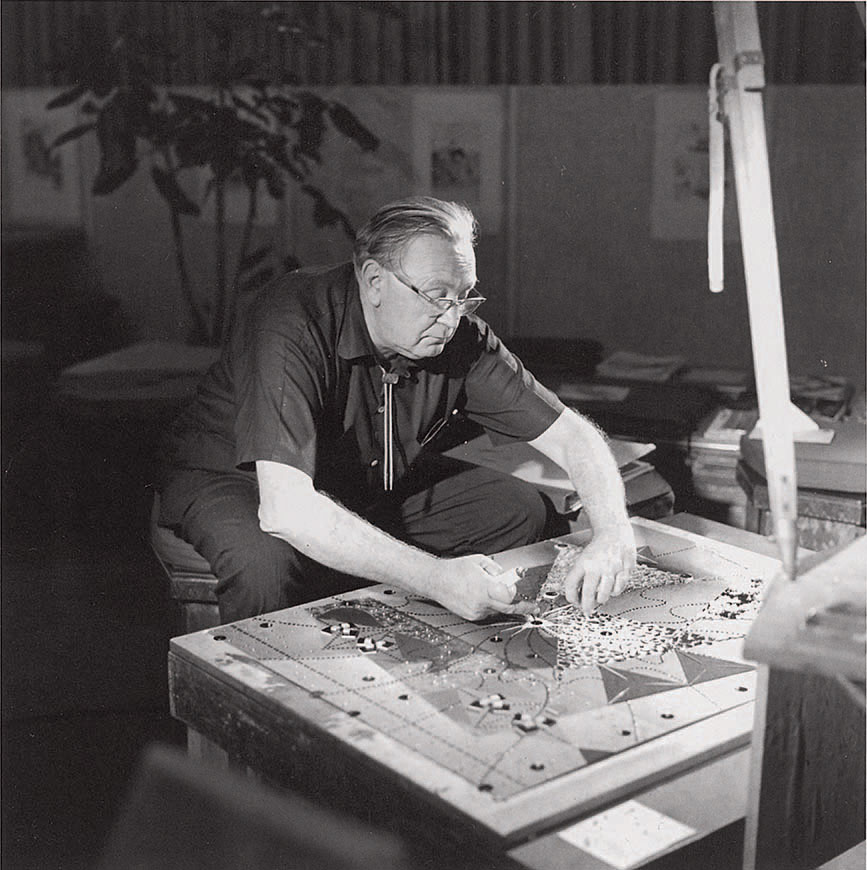

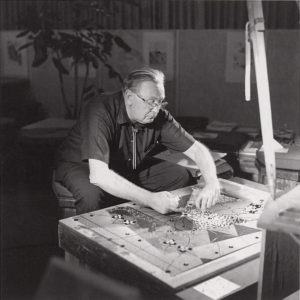

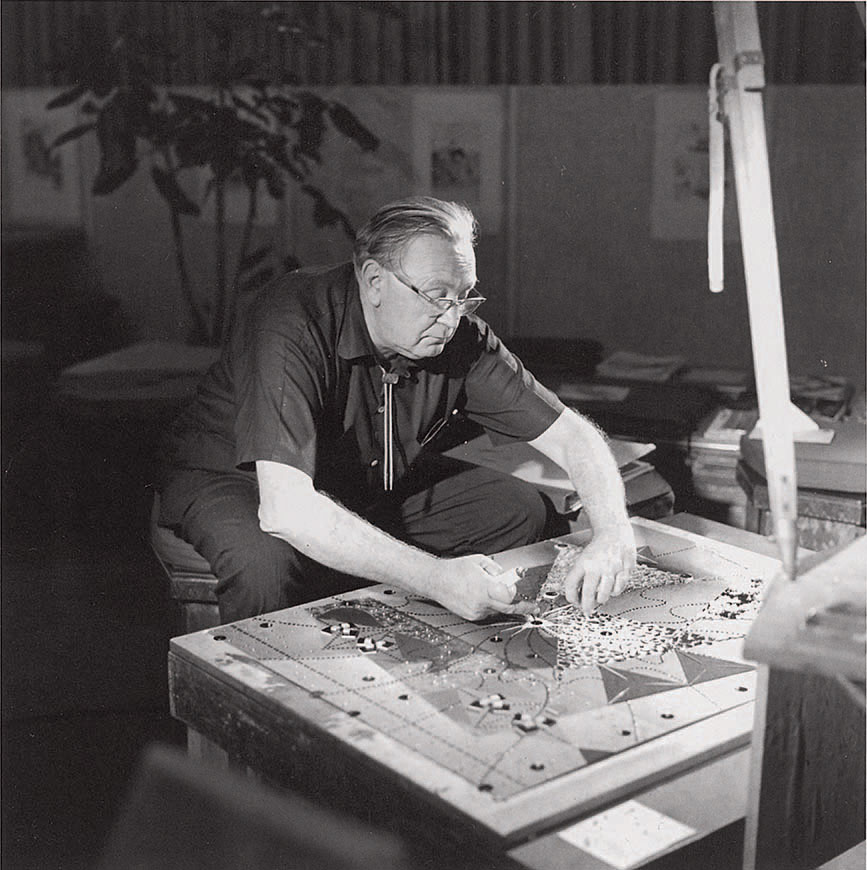

Durst-Gee House images courtesy Abrams, from Great Houses of Texas by Lisa Germany, photography Grant Mudford, published 2008. LACMA image courtesy archinform.net. Bavinger House exterior courtesy archinect.com, interiors courtesy archdaily.com, ngansanova.livejournal.com. Bruce Goff black-and-white portrait, Bruce Goff: A Creative Mind, courtesy Goff Archive, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago; digital file @ The Art Institute of Chicago. Bruce Goff color portrait courtesy architectureweek.com.

Check out this rare footage of Goff at his Shin’en Kan masterpiece, filmed in 1981.

_md.jpeg)