Anne Bass’ Stunning Home in Fort Worth — Get a Rare Look Inside a Paul Rudolph Masterpiece

Powerful Texas Patron and Philanthropist Always Gave Back

BY Rebecca ShermanExterior of the 1970-designed Bass house in Fort Worth. (Photo by Scott Frances/Otto)

Anne Bass, a philanthropist and cultural force in both Fort Worth and New York, died on April 1, 2020, reportedly after a long illness. She was 79. With her former husband Sid Bass, the billionaire Texas oilman, she was a leading figure in Fort Worth’s art and culture scene, beginning in the late 1960s. A 1987 Texas Monthly cover story, titled “The Empress of Fort Worth,” detailed her impact as a taste maker and patron, a role that continued when she began spending more time in New York. In addition to her devotion to the opera, ballet, and museums, Bass was a champion of great architecture.

Her dazzling house in Fort Worth, designed in 1970 by Paul Rudolph, still stands as one of the country’s most remarkable achievements in residential architecture. The Basses commissioned the house while they were still in their 20s and over the years, they filled it with an unrivaled collection of modern art and furnishings. Here, we are reposting a story featuring the house and Rudolph’s work, which originally ran in PaperCity‘s September 2019 print issue.

In the 1970s, fashion designer Halston hosted infamous parties at his Manhattan townhouse for a Studio 54 crowd that included Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Liza Minnelli, and Jacqueline Onassis. Designed by architect Paul Rudolph in 1966, the glamorous four-story residence — dubbed 101 after its address on East 63rd Street — was the ultimate party pad.

It was also classic Rudolph, with a complex layout of terraced levels, floating staircases and catwalks. After Halston’s death in 1990, the townhouse changed hands twice, then went on the market in 2011, where it languished for almost a decade without a buyer. Rudolph, who was once one of the most acclaimed and influential architects of the 1960s, had fallen out of fashion.

Even Halston’s cachet, it seemed, couldn’t regenerate interest in the architect’s work. Around the country, many of Rudolph’s once prized Brutalist buildings were either falling into neglect or facing the wrecking ball.

There was a time, however, when America couldn’t get enough of Rudolph’s work. A student of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius at Harvard University, Rudolph quickly made a name for himself in the ’40s and ’50s designing modernist beach houses along Florida’s central west coast. A pioneer in the architecture movement known as Sarasota Modern, Rudolph designed noteworthy houses, schools, and other buildings with open plans, walls of glass, and cantilevered overhangs.

He was a genius at manipulating space and light, and experimented with reinforced concrete, a material he used throughout his career. By the 1960s, Time magazine had lauded Rudolph as an “architectural wunderkind” whose work had already eclipsed Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier.

At Yale University, where he was the chairman of the department of architecture from 1958 to 1964, Rudolph turned the school into one of the most important places to study architecture in the world. (Two of his students, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers, went on to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize.)

His design for Yale’s Art & Architecture Building put Brutalism on the map in the United States, with heavy blocks of textured concrete masterfully juxtaposed with glass and steel. The building’s remarkable interior featured an open plan with multiple terraced levels, and an exquisite play of light and shadows, reminiscent of his Sarasota houses. At first celebrated for its forward design, the building was later vilified as an example of Brutalism’s soulless and hulking nature.

A mysterious fire destroyed much of the building in 1969, presaging a backlash against Brutalism — and Rudolph — that lasted for decades. Almost 40 years lapsed before the Yale building, in 2008, was finally restored to its original design. It has since been renamed Rudolph Hall.

Today, renewed interest in Brutalism has put the spotlight on Rudolph once again. Architectural Digest and The New York Times marked his 100th birthday last year with articles touting his legacy. (Rudolph, who spent his last decades designing skyscrapers in Asia, died in 1997).

Two of the architect’s most famous residences — the Halston House and the Umbrella House in Sarasota — have recently been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Halston house, which struggled for so long to find a buyer, sold in January 2019 for $18 million — this time to another celebrated fashion designer, Tom Ford, who is restoring it.

Fort Worth’s powerful and philanthropic Bass family was one of Rudolph’s most important patrons during the ’60s and ’70s. A Yale graduate and heir to his uncle Sid Richardson’s ranching and oil fortunes, Perry Richardson Bass gave Rudolph his first Texas commission.

Completed in 1966, the Sid Richardson Physical Sciences Building at Texas Christian University is Rudolph at his Brutalist best: a concrete and cantilevered monolith conceived as an addition to the older, Art Deco–inspired Science Building on University Drive.

A Remarkable Bass Home

As the 1970s brought cultural change and a distaste for the Brutalist aesthetic, Rudolph flirted with using glass in lieu of concrete. His first glass skyscrapers, Fort Worth’s City Center twin towers, were built for Sid Bass and the Bass Brothers Enterprises in 1979.

During this decade, Rudolph also created a number of remarkable residences, including his own Manhattan penthouse on Beekman Place. A tour de force of light and space, it served as the architect’s laboratory of ideas, with 27 terraced levels, treacherous bannister-free catwalks, and a steel skeleton clad in mirror-finish Formica. The building became a New York City Landmark in 2012.

But nothing comes close to the sheer beauty and complexity of Rudolph’s Bass house in Fort Worth’s Westover Hills. Anne Bass and her former husband, Sid Bass, commissioned the house in 1970, while they were still in their 20s and just a few years out of college. Both were admirers of Rudolph’s work.

Sid had been at Yale during the architect’s heyday, and while at Vassar. Anne had attended Yale lectures taught by the great architecture critic and historian Vincent Scully, according to a 1991 House & Garden story about the house. The Bass house had been off limits to the media until the House & Garden article ran 28 years ago, and very little of it has been seen publicly since — until now.

Framed in steel and enclosed by glass and aluminum, the all-white house is light and transparent, recalling the work of two of Rudolph’s biggest influences, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. The architecture also reflects Anne’s own minimalist aesthetic and preference for straight lines — there’s not a single curve in the house.

Essentially made up of rectangular planes that hover over the hilly terrain, the house has three main stories that are subdivided into 12 levels with 14 different ceiling heights, and a small penthouse. Dramatic cantilevers jut above the ground and include the swimming pool and an automobile courtyard. Visitors enter the house under an astonishing 40-foot-long cantilever.

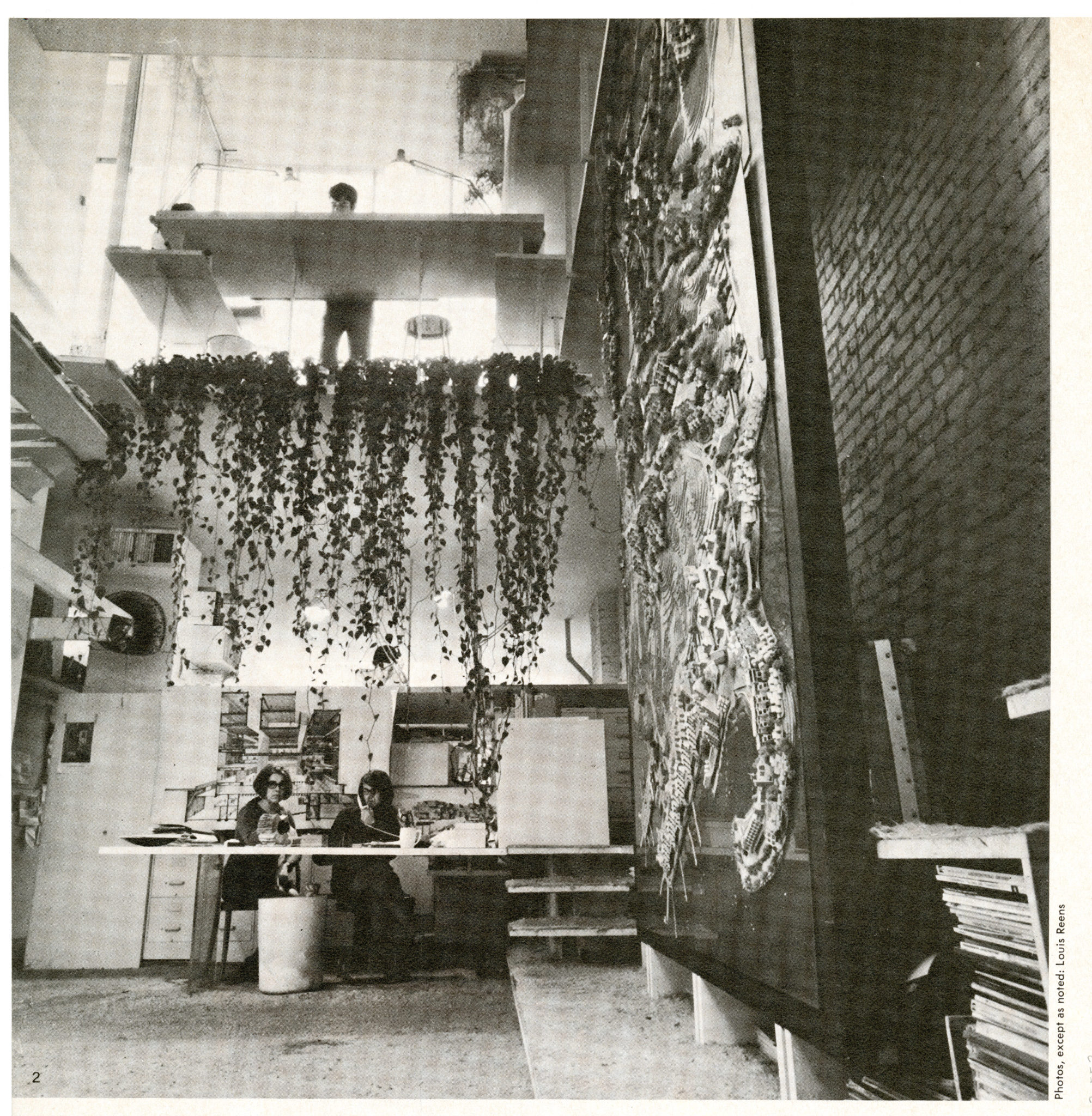

Inside, Rudolph choreographed space like dance moves, with a boggling series of steps and landings leading to sunken and elevated areas. Intimate spaces with low ceilings open into larger double-height rooms. A more kinetic house has yet to be devised, and it all makes sense: Anne was trained in ballet, and dance served as one of Rudolph’s inspirations for the house.

“The ideal of weight and counterweight, similar to the movement of the human body, became the genesis of the house,” Rudolph told House & Garden writer Mildred F. Schmertz.

The house is designed to showcase extraordinary art — and for good reason. At the time of the 1991 House & Garden feature, the article prominently spotlighted Anne’s collection of works by Mark Rothko, Alexander Calder, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Morris Louis, Henri Matisse and Andy Warhol. Rudolph designed some of the furnishings himself, including leather banquettes in the sunken living room and a floating platform bed for the master bedroom, mixing it with iconic Mies van der Rohe Barcelona chairs and Cedric Hartman lighting.

Rudolph collaborated on the design for the property’s extraordinary grounds with modernist landscape architect Robert Zion, while British garden designer Russell Page created the formal and classical aspects, including a striking allée of pleached oaks and a reflecting pool for Aristide Maillol’s large recumbent nude sculpture The River. There’s also a rose garden, wisteria-covered pergola and a Rudolph-designed greenhouse. Anne, an avid gardener, has maintained the gardens impeccably, along with the house’s architecture and interior furnishings, which largely remain unchanged.

Rudolph considered the Bass house his best residential work, and it remains as an enduring tribute to the under-appreciated architect who had an eye for merging beauty with experimentation.

“Rudolph’s influence is not yet fully recognized, but he’s on par with any architect of his generation,” says Dan Webre, an architect and board member of the Paul Rudolph Foundation in New York City. “A lot of his ideas are just now becoming mainstream.

“If you think of Zaha Hadid, it’s safe to say she was influenced by Rudolph. He paved the way for new ideas about space and new materials. He was always pushing the envelope.”

_md.jpg)