The ultimate white-tie gala gown, designed by Charles James.

Dominique de Menil first came to know Charles James when a New York neighbor asked her to deliver a note expressing the neighbor’s desire to never see or speak to the couturier again. This brought Dominique into James’ orbit for the rest of his life. Not only would their relationship have sartorial implications for Dominique, but it ultimately resulted (at the recommendation of her husband, John) in James being engaged to decorate the interior of their Philip Johnson-designed house on San Felipe Street in Houston — the only interior James ever realized as a professional commission. This unique history is what The Menil Collection explores in the upcoming exhibition “A Thin Wall of Air: Charles James,” curated by Susan Sutton (May 31 – September 7). The designer is also the subject of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute’s “Charles James: Beyond Fashion” (May 8 – August 10) — the inaugural show in the newly renamed Anna Wintour Costume Center that will kick off with the annual Met Gala. But here at the Menil, visitors will see a more complex picture of James’ aesthetic, beyond his fashion design, thanks to the visionary’s unique relationship with the de Menil family.

WHO WAS CHARLES

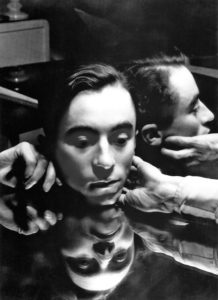

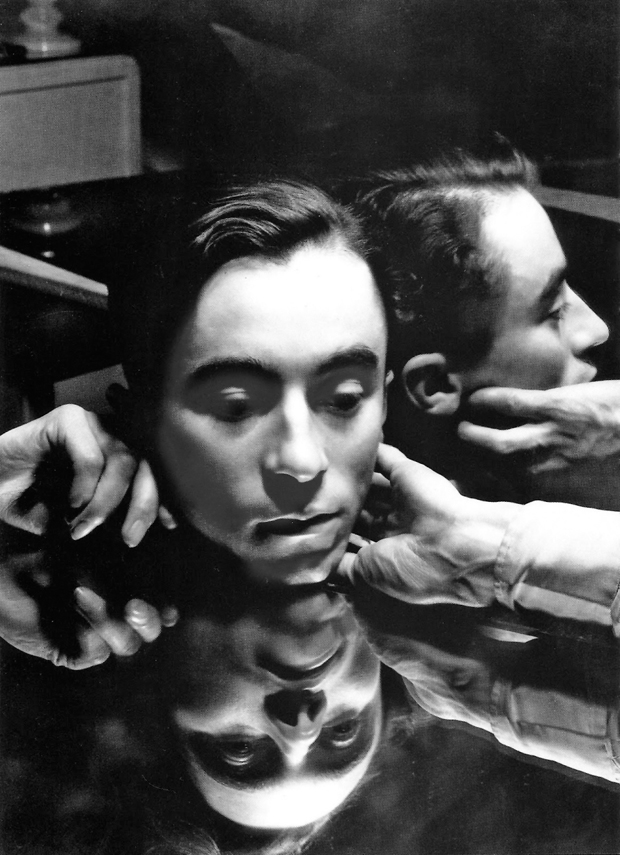

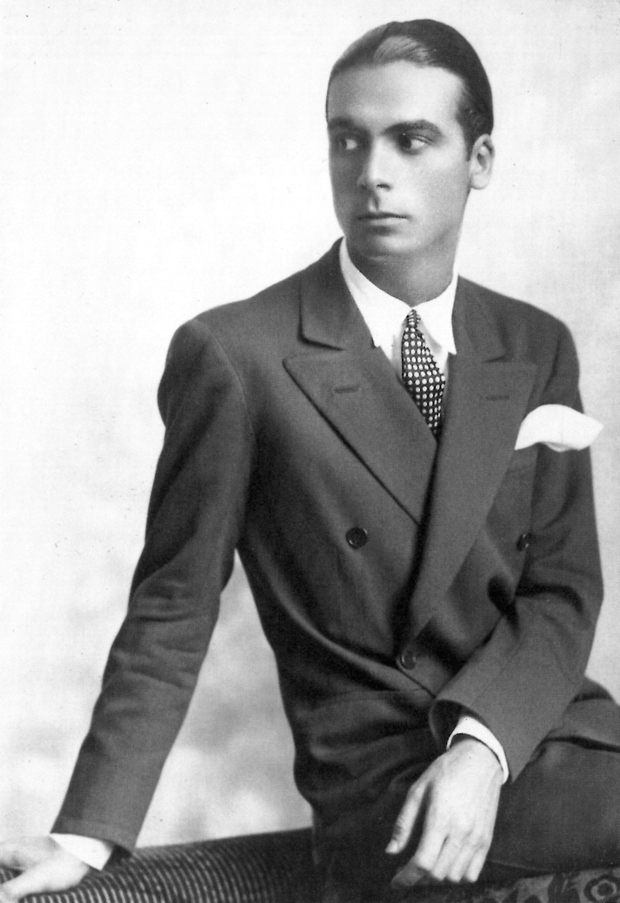

“Unrelenting” and “single-minded” perhaps best describe the iconoclastic Charles James. He was born in 1906 at his family’s home Agincourt in Camberley, a small town in the southeastern English county of Surrey. His mother was a patrician American from Chicago; his English father, educated at Eton (which James’ grandfather helped a young Winston Churchill be admitted to), was an instructor at Sandhurst’s Royal Military Academy. Charles was steeped in luxury from an early age. At age 13, he was sent to England’s Harrow boy’s school, where he became chummy with the pre-teen Cecil Beaton, Evelyn Waugh and Sir Francis-Rose. It was here that his first flair for excess (in this case, intimate relations with a classmate) would meet with admonishment, with his immediate expulsion in his third form.

After an interlude at the University of Bordeaux (as a primer to Oxford) came to naught, he moved to America and settled on millinery after unsuccessful stints in Chicago pursuing architectural design and working at the Chicago Herald Tribune. This indelibly influenced his impending transition into clothing design and shaped his creative methodologies —adopting techniques (such as sculpting directly atop forms) and cultivating an appreciation and fluent use of structural materials such as millinery wire and stiff buckram. He soon grew tired of hats and sought out a more compelling form of creation. In 1928, he began making garments. His success was immediate, due to the astonishing confections he would dream up in utterly heartbreaking color schemes. For his mille-feuille like evening-gown skirts, he often layered some 50 pieces of tulle atop one another; the result was a sumptuous tonal amalgamation. James further explored color through almost oppositional choices of hue for the linings of his restrained dinner jackets. But the signature fascination of his work was form in all its nuanced glory. His interest in garment creation can be likened to that of an artist; it became the sole focus of everything he would create in his lifetime. Unlike most fashion designers, his couture was not reactionary, nor envisioned as specific to a season. Instead, he created from an unyielding desire to construct a pleasing garment for his clientele. In fact, he famously made clothing only for those of whom he approved.

As is often the case for the highly strung and perfection obsessed, James was often underwhelmed when the lady who commissioned a gown arrived at his studios for a fitting. Because of the frantic pace and crazed environment James preferred, said fitting might only take place hours before the occasion for which the piece was being made. For better or worse, James was entirely unconcerned with practical considerations. He found them banal and irrelevant compared to his devotion to his many sublime, astonishing works. It was James who, in 1937, devised the first quilted puffer jacket. His was eiderdown filled white satin, which Salvador Dalí called the first piece of soft sculpture. The Victoria & Albert paid a then record sum for it.

It was the silhouette that James magnified and manipulated in all its variations, through medium and a dazzling technicality of cut, construction and finish. He famously worked and reworked pieces by himself to perfectly create the drape or movement he sought. In fact, for a 2011 exhibition at the Chicago History Museum, fully grasping the interior construction of a gown without disassembling it required a CAT scan. He chose his materials like an artist, utilizing whatever was necessary to achieve a desired look. Thus, disparate features such as zippers can be found in gowns with a boned bodice — an entirely unorthodox pairing at that time. Yet parallel to the art behind his work was his prescient awareness of the technical developments and modern demands of clothing. His Taxi dress, its name derived from the wear’s ability to don it in the backseat of a cab, is an example. He also realized a measurement system for patterns of mass-produced clothing and, after the birth of his first child, designed a line of children’s clothing that was not only practical but sensitive to the manner in which a child moved. (One fan of his children’s line was Grace of Monaco, who purchased his designs for the newborn Princess Caroline.)

Ultimately, however, James’ wholehearted devotion to his art would be his ruin. He was so absorbed in his craft that he was reduced to living in a suite of rooms at the Chelsea Hotel, where the more obliging of his patrons — including Elsa Peretti — continued to underwrite his life and work. His marriage to patron Nancy Lee Gregory (with whom he had a son and daughter) dissolved in 1961. In 1964, he made the acquaintance of iconic illustrator Antonio Lopez, who chronicled James’ work until the end of his life. In the intervening years, James often lectured and briefly collaborated with Halston (who would, in time, become a collector of James’ noted erotic drawings). After one of these collaborations met a tepid response, the close relationship unraveled.

James became the only clothing designer to ever receive a Guggenheim fellowship — just four years before his death from pneumonia in 1978.

CHARLES GAVE ME A FREEDOM THAT I NEVER LOST AND THAT WILL CHERISH FOREVER. — CHRISTOPHE DE MENIL

DOMINIQUE AND CHARLES

Charles James entered the life of the de Menil family in the late 1940s. Dominique met him entirely by happenstance when a neighbor at 111 E. 73rd in Manhattan, Princess M. Ruspoli, Duchess de Gramont (who figures largely in Marcel Proust’s Remembrances), asked her to deliver a note expressing Ruspoli’s hope to never see or speak with James again. In so doing, de Menil met the designer and soon had James making pieces for her. In the ensuing years, John and Dominique de Menil, and their children Marie (later called Christophe), Adelaide, Georges, Francois, and Philippa (later Fariha) opted to live more permanently in Houston. Unhappy with their current house in River Oaks, they decided to build their own. They tapped architect Philip Johnson for the onestory abode on San Felipe, hidden behind a sinuous brick wall and grove of bamboo shoots; it was one of Johnson’s earliest residential commissions. Towards the end of construction, John proposed that they commission Charles James to decorate the interiors, hoping he could mitigate the feeling of transparency that Dominique sensed in Johnson’s open floor plan. James accepted and arguably made the most significant contributions to the home’s sensibility and scale. He strongly felt that the ceiling needed to be raised upwards by 10 inches — a move that inspired resentment in Johnson, who felt his work was being defaced by a mere dressmaker, a sentiment that dissipate over time.

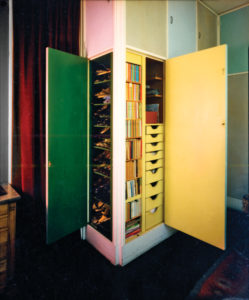

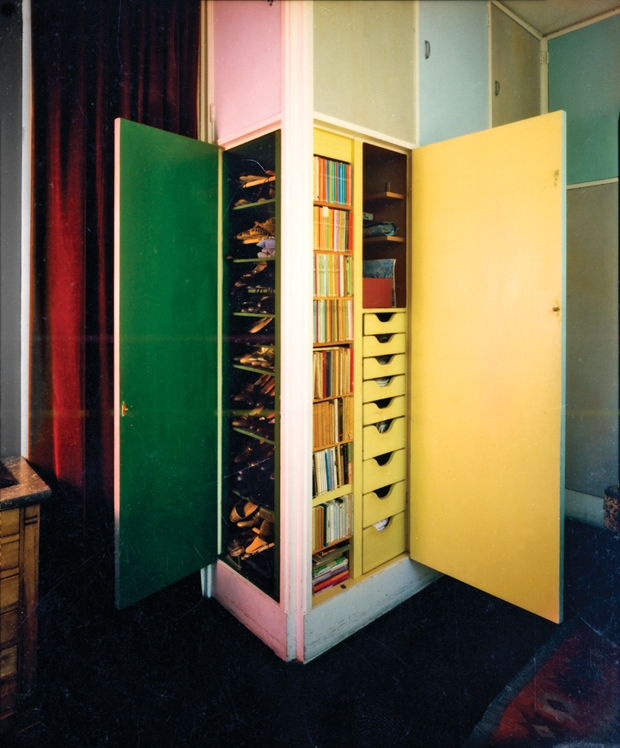

James’ decisions for the space directly mirror how he constructed his garments. He started with color. He arrived everyday from the Warwick Hotel, dressed in a khaki jumpsuit, and used the garage as his studio. He refi ned his plans by using a board for each room, on which he would test out color combinations until perfected. Having settled upon a specific palette, he would then mix each color expertly. This could last well beyond sunset, oftentimes resulting in the eldest children, Christophe and Adelaide, being asked to hold lights so James could continue mixing. This involved process brought color into every area of the house he felt needed it. Just as he gave nuanced color choices greater impact by incorporating them into the most intimate portions of his garments, so did he paint the most personal points within the house in the most remarkable tones. Examples include the hallway just outside the daughters’ bedrooms, the interior of both the storage closet off the living room and the bar, and within Dominique’s dressing room, where every door hinged to the L-shaped corner wardrobe is painted a different harmonious external color, with the edges and interiors acting as complements. Further amplifying color choices within the house was James’ desire to accentuate the spatial beauty of the home through surface treatments such as applying butterscotch felt on the walls both inside and directly outside a guest powder room off the entry. Within the hallway directly outside the girls’ rooms, two sets of double doors were installed. The outermost faces were left a muddy gray to match the hallway, while the back side was outfitted with mirror, the secondary door was covered in vermillion felt, and the most interior face of the door was covered in antique French cerise velvet.

He designed three pieces of furniture for the house with exacting detail: a pair of sensual sofas (actually conjoining settees), a chaise longue for the living room and a banquette for the playroom-cum-dining room. Their adherence to curvilinear forms have distinct overtones of his garment making. James insisted that every surface of the sofa slope — an effect he achieved with convex reversed curves created by an internal structure of metal bailing; it took five different artisans, each successively working for six months, to complete the wool-covered pair. (The upholstered banquette also adheres to this rule of organic shape, but it cannot impart the impact of the bombastic duo of sofas.) The chaise longue, where John would read the morning newspaper, was positioned against the backyard-facing floor-to-ceiling windows. Its wrought-iron frame, meant to evoke the elegant and fluid movement of a deer’s leg, was made from pine slats and upholstered in buttoned saffron and gray raw silk.

Dominique continued to have dresses made by James once the house was completed. She also had him design a couture gown for Christophe for her debutante ball in 1952, which she wore for debuts at both New York’s Knickerbocker Club and here in Houston as well. In typical James fashion, he insisted that the outer layer of dress be shades of silver and royal blue in New York; then, when she wore it in Houston, he outfitted the outermost skirt in pure tones of off-white and ivory. Christophe remembers feeling “very special and very alone” in the gown and that “it would carry you almost” as one moved it about, the skirt echoing the forward and backward motion of a bell. Indeed, inhabiting a James gown placed the wearer in an alternate reality of highly labored perfection. “You couldn’t sit,” she said. In fact, when dressing on the night of her Houston debut, the zipper broke, and she had to be sewn into the gown. Adelaide, too, would enjoy the designs of James. Indeed, it seems the legacy of Charles James dressing de Menil women continues still, as Christophe plans to bestow her other James gown — a sleeveless ensemble with a black satin bodice, bow and an enormous pink skirt — upon her great granddaughter, Secret Snow (daughter of the late artist Dash) when the time is right.

RENEWED INTEREST

Is the current reemergence of Charles James proof that we’ve met the tipping point for unstructured clothing (a style that can only be likened to “non-dressing”), or is the resurgence of interest mere happenstance? Contemporary ready to wear, both in America and abroad, seems uninterested in the evolved construction and high standards à la James. Yet designers such as Ralph Rucci have long been inspired by his creations, even though no one has truly evolved the ideas that James himself developed almost 75 years ago. Zac Posen perhaps distills the most James-like qualities relating to color and form, having imbued both his spring/summer ready-to-wear and pre-fall collections with the delicate and unexpected hues, as well as intelligent and thoughtful construction. Of course, following both 2014 exhibitions, Charles James may finally achieve the level of appreciation that he always sought but never attained in his lifetime.

_md.jpeg)