Peter Saul in his Germantown, New York, studio, 2020. The artist is the subject of a major survey, at the New Museum, NYC. Significantly, six seminal canvases in the 60-works exhibition are owned by Dallas collectors. (Photo by Katherine McMahon)

Editor’s note: In an exclusive for PaperCity, Chris Byrne, co-founder of the Dallas Art Fair and owner of the Elaine de Kooning House, writes about an artist whose connection to Texas is legendary — the iconoclastic, controversial Peter Saul. Chris Byrne visits with the painter about the backstory of six significant early canvases in his latest museum exhibition.

In dual shows this spring — at Manhattan’s prestigious New Museum and a traveling European museum retrospective — painter Peter Saul has been rediscovered by a new generation of art acolytes. And after knowing Saul for a quarter of a century, it felt like the right time to talk with him about the pivotal canvases in the New Museum survey, all of which have one thing in common: The works are owned by Dallas collectors.

In February, “Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment” opened at the New Museum, and I was there — along with David Byrne, Brian Donnelly aka KAWS, Carroll Dunham, Jeff Koons, John Waters, and Cindy Sherman — for the artist’s reception. The largest survey of Saul’s paintings in New York to date, the exhibition has just over 60 works.

Many of the artist’s earliest paintings in this exhibition were conceived and created in Europe over half a century ago when Saul lived as an expatriate in Holland, Paris, and Rome from 1956 through 1964.

From these distant vantage points, Saul was able to mine American popular culture — from the Disney of his childhood to Mad magazine. Images of Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, Superman, and the villains of Dick Tracy began to populate his canvases, emerging from the dripping brushy strokes so stylish at the time.

In the 65 years since, Saul has created drawings and paintings with images of war, psychology, politics, executions, and the history of art itself, the undulating cartoonish forms impeccably rendered in luminous acrylic.

Although he could initially be dismissed by the mainstream art world, Peter Saul now rightfully appears as one of the major artists of our time.

Saul also has strong local roots. He was a beloved painting instructor at The University of Texas from 1981 to 2000, fostering and shepherding the early work of many students. Erik Parker and Chris Ware are among the most prominent. I’ve been fortunate to associate with Saul for more than 25 years — placing paintings with Dallas collectors, helping the artist organize his 1997 survey at Artpace in San Antonio, and facilitating loans for his U.S. and European retrospectives in France and Germany.

When we recently caught up, Peter Saul was characteristically kind enough to share his latest thoughts about the loans from Dallas collections, which comprise 10 percent of the New Museum show. His direct responses are consistent with his unpretentious approach to every aspect of his life and art-making.

Below, Peter Saul’s insight on these six key paintings, borrowed from Dallas collectors, in his latest museum show.

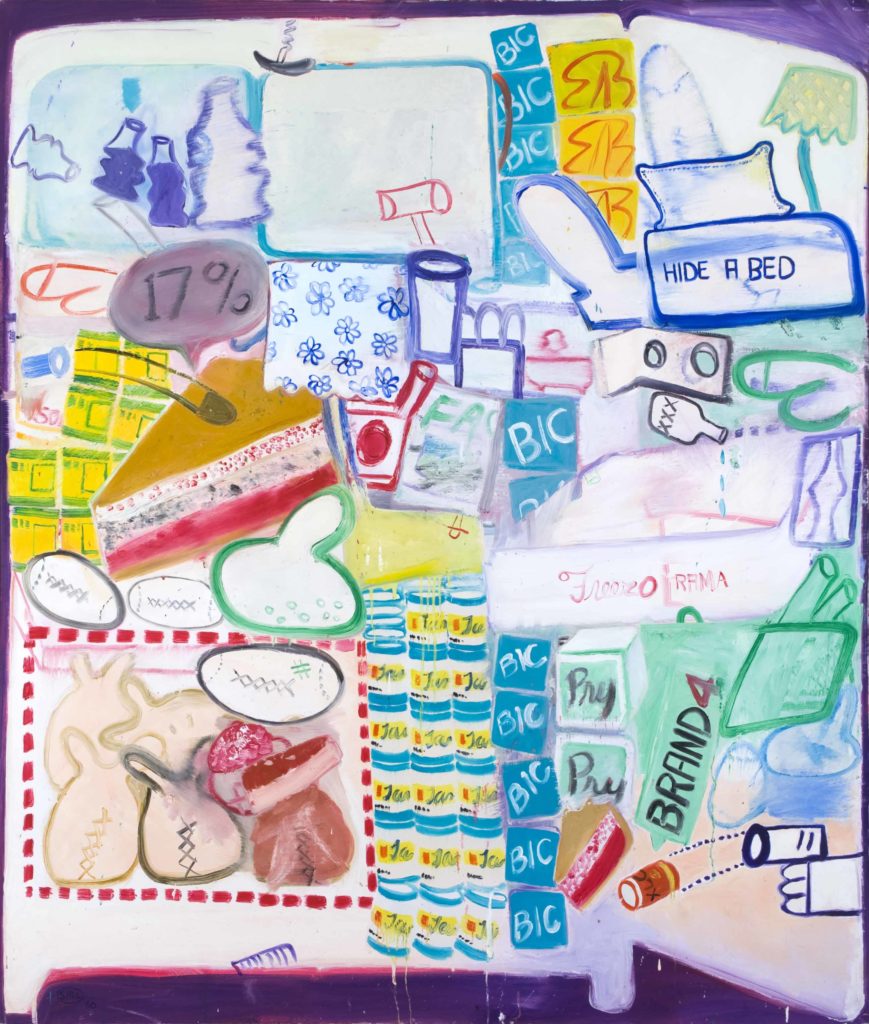

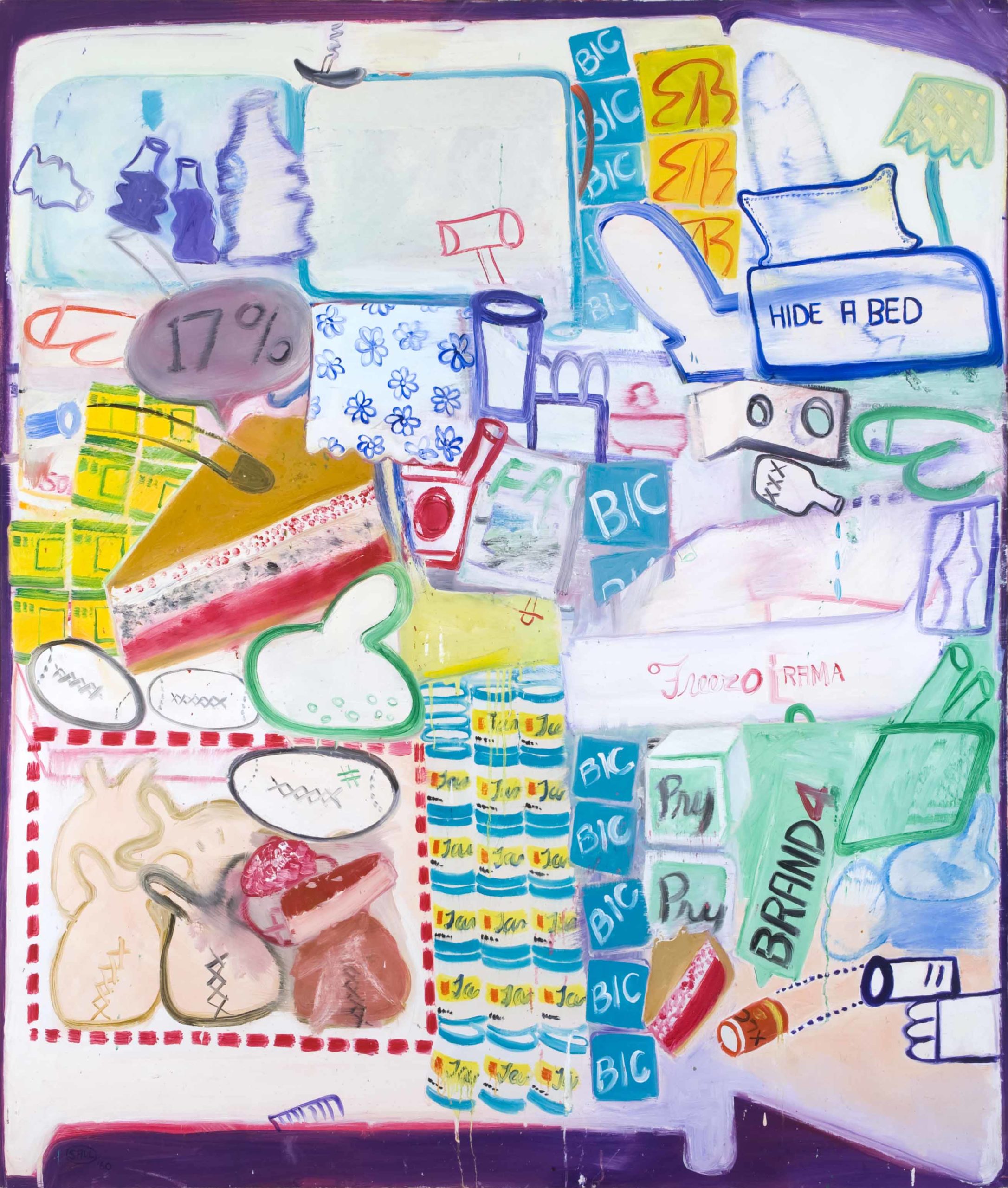

Icebox, 1960, the Harkey Family Collection, Dallas.

Peter Saul’s Icebox, 1960, reveals the artist being among the first to pick up upon the nascent Pop Art movement.

“This was the picture in my first show — in New York, 1962 — that most resembled the then recently coined term “Pop Art.” I think, in retrospect, that was because it had household objects, recognizable as such, even if I had taken some liberties. When I painted it, I hadn’t heard of Pop Art, which turned out to be an official, important art movement that had a lot of stupid rules attached to it — like copying commercial art, no imagination, etc.”

Bathroom Sex Murder, 1961, collection of Mrs. Marilyn Lenox, Dallas.

Peter Saul’s Bathroom Sex Murder, 1961, shows the influence of a celebrated Alfred Hitchcock thriller.

“This is a case where the title — I got the idea from seeing the movie Psycho in Paris, dubbed in French — is way ahead of the painting. I felt the need for maximum sensationalism, but the picture is stream of consciousness, abstract expressionism, not coming close to its title, although I like it anyway.”

Killer, 1964, the Harkey Family Collection, Dallas.

Peter Saul’s Killer, 1964, anticipates works by the painter Philip Guston.

“Lunatic murderer looking for the electric chair so he can sit down and take a rest? Probably I was tired of painting electric chairs so just painted the kind of guy who should be executed. The big finger presses his button, makes him angry. I try to think up exciting subjects — violent, funny, sexy, and surprising — and hope for the best.”

Untitled, 1962, collection of Brett and Lester Levy, Jr., Dallas.

Peter Saul’s Untitled, 1962, demonstrates early use of a cartoon character, a device that would be popularized by Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol.

“At the time, it opened this spontaneous way of thinking things up as I painted the picture, throwing things in to create a story on a certain level. Superman farts, beyond that, who knows? I paint picture by picture. Whether it’s 1960 or right now, l use my imagination to think up an image that is supposed to be interesting to look at for me and the viewer both. Is a picture successful? I have no idea! Of course I don’t let the picture out of my studio if I don’t like it but I have very little idea what anyone else thinks because I know few people.”

“I discovered from reviews of my art, back in the early 1960s, that I was out of fashion, which is not good, of course. But it didn’t bother me very much, because there’s really nothing you can do about someone else’s opinion. Modern art is obviously a “do anything you want” situation, but artists who need to follow rules can do so — or make up rules if they wish.”

Icebox Number 9, 1963, collection Museum of Modern Art, New York, fractional and promised gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bill Lenox, Dallas.

“This later ‘icebox’ has a more thought out and stately appearance. Probably, by this time, I was more conscious of what my art style actually looked like, from reading reviews of my first show. Looks a little cubistic, which I like.”

Columbus Discovers America, 1992-1995, collection of Brett and Lester Levy Jr., Dallas.

Peter Saul’s Columbus Discovers America, 1992-1995, points the way to the painter’s mature work, distinguished by provocative subject matter and a cartoon-based style.

“Columbus is teaching the Caribbean natives an important lesson — quit that cannibalism! Actually, have no idea whether they were cannibals because I work spontaneously, zero research. The picture is influenced by 14th to 15th-century art where the principal figures are very large compared to other things like the boat. Also, Columbus is teaching Christianity by bopping them on the head with the crucifix (notice the Salvador Dalí-style Jesus figure).”

“I always choose unusual subject matter if I can find it because there’s less competition, more likely to be noticed. However, I want to open the pictures up to the unexplainable, crazy, irrational, and just plain stupid, not “get to the point” or have any kind of useful or constructive attitude.”

“Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment,” at the now closed New Museum, New York, scheduled to be on display through the summer. Check back at the museum site for any possible reopening news; order the catalog here.

Watch Peter Saul talk about his art style here.

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)