Itzhak Perlman, the Rare Violin Superstar, Thrills a Symphony Audience — Ending His Run In Houston With the Fiddler’s House

Putting Klezmer Music's Joyful Sounds in the Spotlight

BY Adrienne Jones // 07.04.24Legendary violinist Itzhak Perlman concluded his Houston Symphony tenure with a performance of his "In the Fiddler's House." (Courtesy Houston Symphony)

“The inner history of a people is contained in its songs.” — Rabbi Adolf Jellinek (1821 to 1893), chief rabbi of Vienna

Neither soaking rains nor even a tornado warning in the afternoon could dampen anyone’s spirit as they poured into Jones Hall for Itzhak Perlman’s concert, “In the Fiddler’s House,” which capped his tenure as artistic partner with the Houston Symphony.

Perlman’s nine performances over the last three seasons made him a beloved figure on the Houston performing arts scene. He regularly earned the type of thunderous ovations that have marked his career as one of the few living classical musicians to gain megastar status. His well-seasoned technical virtuosity combined with an uncommon charisma brings audiences close to him, feeling at once awestruck by his musicality and the impulse to cheer him on as his 79th birthday approaches in August.

Nearly every seat was filled for the special, one-night performance. Rather than a concert taken from the standard classical canon, Israeli-born Perlman put on an evening of Klezmer music – the sometimes soulful, sometimes joyful folk-style music developed by Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe over the last 1000 years.

Many Americans were first introduced to Klezmer music by Itzhak Perlman’s 1995 In the Fiddler’s House, produced as part of the Great Performances series for PBS. Filmed in Poland, the birthplace of Perlman’s parents, the documentary was a big hit with TV viewers, winning Perlman his third of four Emmy Awards.

Now, almost 30 years later, the touring In the Fiddler’s House concert is still thrilling audiences, including many introduced to Klezmer music by composer Jerry Bock’s score for the internationally popular 1964 Fiddler on the Roof Broadway show. The music shaped by its Middle Eastern scales and vast range of emotionality, from haunting melodies marking sorrow and loss to unparalleled expressions of joy and celebration.

Although Bock said he was influenced by the Russian Klezmer he heard growing up, it’s easy to hear musical strains from the many different areas of Europe and Asia where Jewish people have lived. In the United States, Klezmer reflects the sound colors of big band, swing, jazz and even hoedown.

Klezmer enjoyed an enormous revival during the 1970s and 1980s following the release of Fiddler on the Roof, and interest has continued. In recent months, Perlman and a roster of Klezmer stars and members of the Klezmer Conservatory Band, some who played in the 1995 documentary, have performed in San Francisco, Bethesda and Palm Beach. They will be in Kansas City this September.

Fiddler Perlman

As the lights dimmed, Jones Hall buzzed with greetings and anticipation. The stage was already set with a piano and some of the instruments that comprise the band, including an accordion, mandolin, drums, double base, saxophone, clarinet, two violins and two trumpets.

Commanding attention downstage was a rarely seen trapezoidal wooden box with strings, an instrument of the dulcimer family, known in a Klezmer band as a tsimbl, or the Ukrainian version of the hammer dulcimer. That night, the tsimbl would be played by the strikingly talented virtuoso Pete Rushefsky. Rushefsky serves as executive director of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance, which has worked to preserve and present immigrant performing arts traditions in New York City since 1968.

Interestingly, there is a music luminary well known to Houstonians who is also a master of the tsimbl, known in English as a cimbalom. Houston Symphony conductor Juraj Valčuha has charmed listeners and readers with the story of his youthful ambition to become a professional cimbalom player — until he was dissuaded by his father’s concern about sufficient career opportunities for cimbalom specialists.

As the musicians arrived on stage, the audience erupted in a salvo of applause, as if welcoming friends. An even louder wave of cheers greeted Perlman as he took his place with the broad smile Houston audiences have come to expect and appreciate.

Hankus Netsky, the music director, arranger, saxophone player, pianist and founder/director of the Klezmer Conservatory Band, served as a genial master of ceremonies. Each selection was thoughtfully selected and beautifully rendered, but a few stood out.

The first piece, Netsky noted, embodied the spirit of a Jewish wedding with the special music for a bride’s entrance known as the seating of the bride. It’s hard to imagine a more haunting and mysterious melody as the bride approaches her destiny and becomes a link in a chain of Jewish continuity that reaches back, by some estimates, 3,800 years. Netsky revealed that the music was designed to make the bride shed tears on what traditionally was considered the most holy and important day of her life.

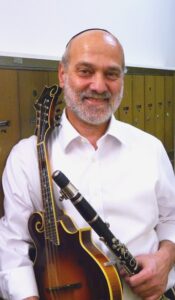

Another breathtaking traditional piece is Shalom Aleichem, which welcomes the angels to the Friday night Sabbath table in a Jewish home. This rendition was played exquisitely on the mandolin by Andy Statman. Statman is also famed in Klezmer circles as a clarinetist and former student of Dave Tarras, one of the most important Klezmer musicians of the last century. Statman has played in more than 100 recordings and in 2012 received the National Heritage Award from the National Endowment for the Arts — the highest honor given to tradition-based musicians and artists in the United States.

An excellent opportunity to hear Perlman in a duet with a solo voice was the moving Yism’chu, a prayer from the Friday night service in the synagogue:

“Those who keep the Sabbath and call it a delight shall rejoice in Your kingdom…

This day is sanctified and blessed by You, the most precious of days, a symbol of the joys of creation.”

Also quite magnificent was the processional that was played at the wedding of Perlman’s daughter — a moving, haunting melody that felt like an inexorable march, a sound pushing forward from an ancient past into the future.

Not all of the songs were serious. The band performed spirited numbers that mark the fall holiday Simchat Torah, some going faster and faster like a tarantella, with Perlman accelerating the tempo and the concert hall coming alive. The music fueling the audience and the energy from the audience fueling the musicians.

However, nothing could match the excitement and energy of when the crowd was invited to dance. People didn’t have to be asked twice. House lights were ordered Up and suddenly almost everyone was on their feet.

To the driving rhythm of the famous folksong, Hava Negila (“Let us rejoice”), spouses, friends and strangers extended hands to each other to dance the hora — the celebratory circle dance that is a staple at nearly every Jewish wedding and bar/bat mitzvah. Anyone left in their seat was clapping to the music. Young and old, arm-in-arm, circles broke apart as lines of dancers snaked their way through the rows and up and down the aisles. While they danced together, many private memories were no doubt recollected and celebrated that night.

The high spirits in Jones Hall after the dance were the perfect segue for one of the evening’s most rollicking songs, with Perlman’s spirited violin accompanied by one of the vocalists. There were no lyrics — just “di di di” — but they were sounds coming from the soul.

No words were required. Soon the band joined in with an alto sax and triumphant trumpet solo, and the exuberance was almost as big as Klezmer music’s history is long.

_md.jpeg)