Remembering Artist Mac Whitney, A Texas Art Superhero Who Transcended the Limits of Steel

Creator of Colossal "Houston" Sculpture is Celebrated by Friends, Colleagues

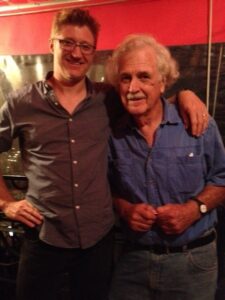

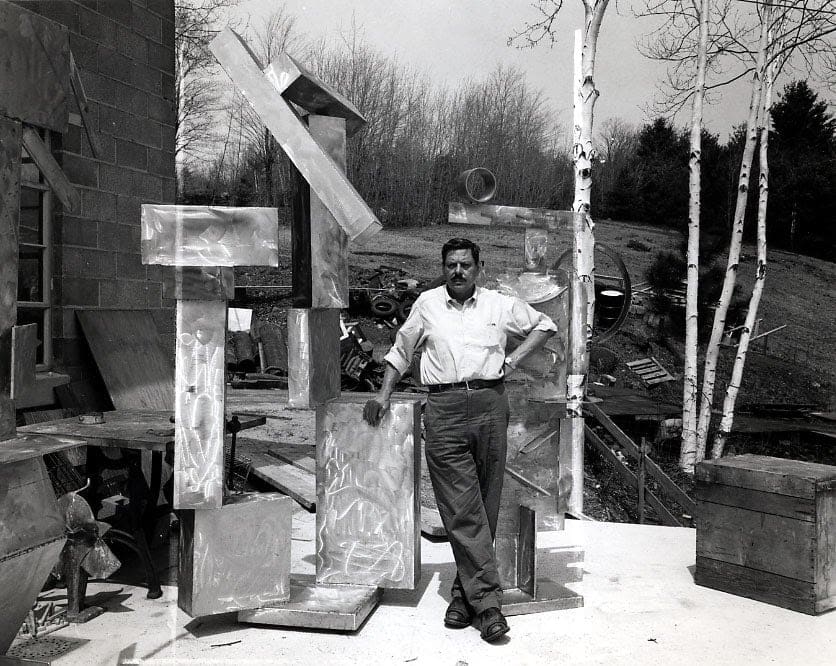

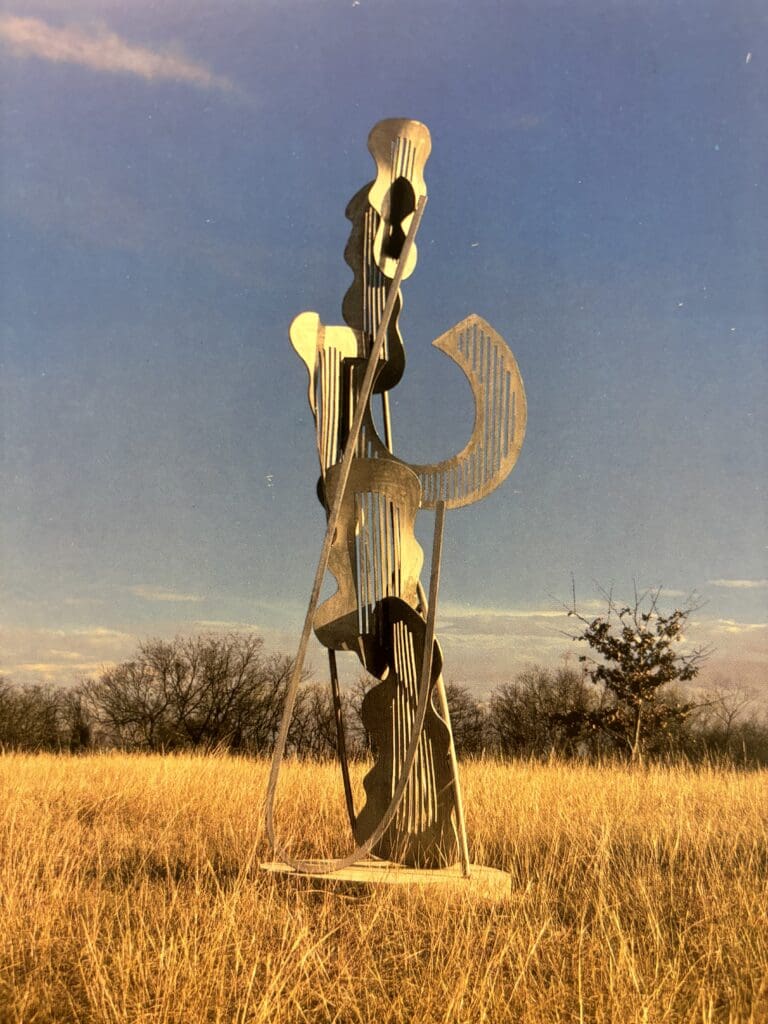

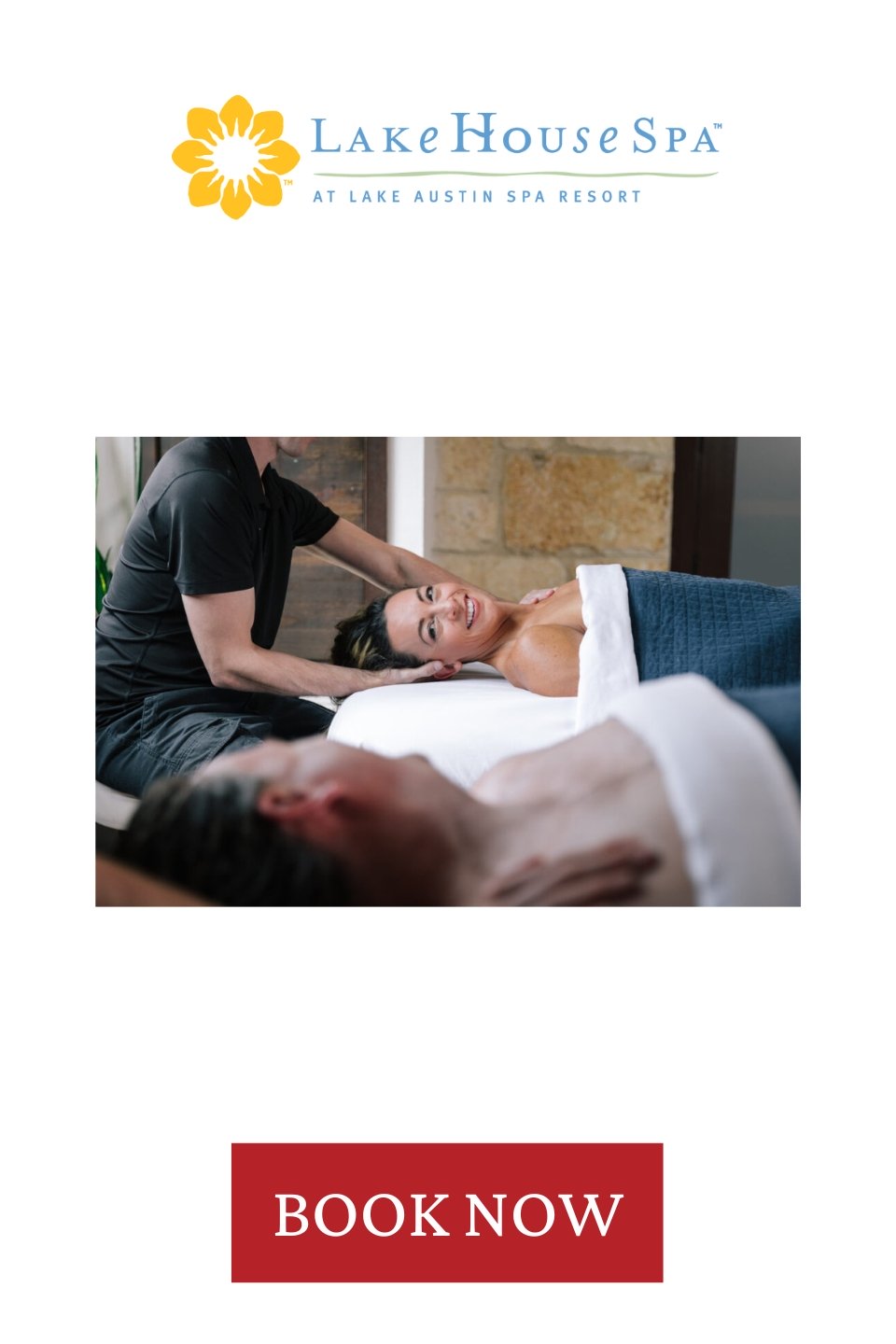

BY Ericka Schiche //Artist Mac Whitney stands near one of his steel sculptures in Oak Cliff, circa 1976. Whitney resided in Ovilla, Texas near Dallas for many years. (Courtesy Dallas Museum of Art)

Beloved innovative sculptor and Texas art legend Mac Whitney (1936 to 2025), who passed away earlier this spring, embodied the rugged individualist archetype. Whitney’s versatility and ingenuity as a sculptor who worked fearlessly with acrylic and steel materials gave him a lifelong advantage within the sculpture medium.

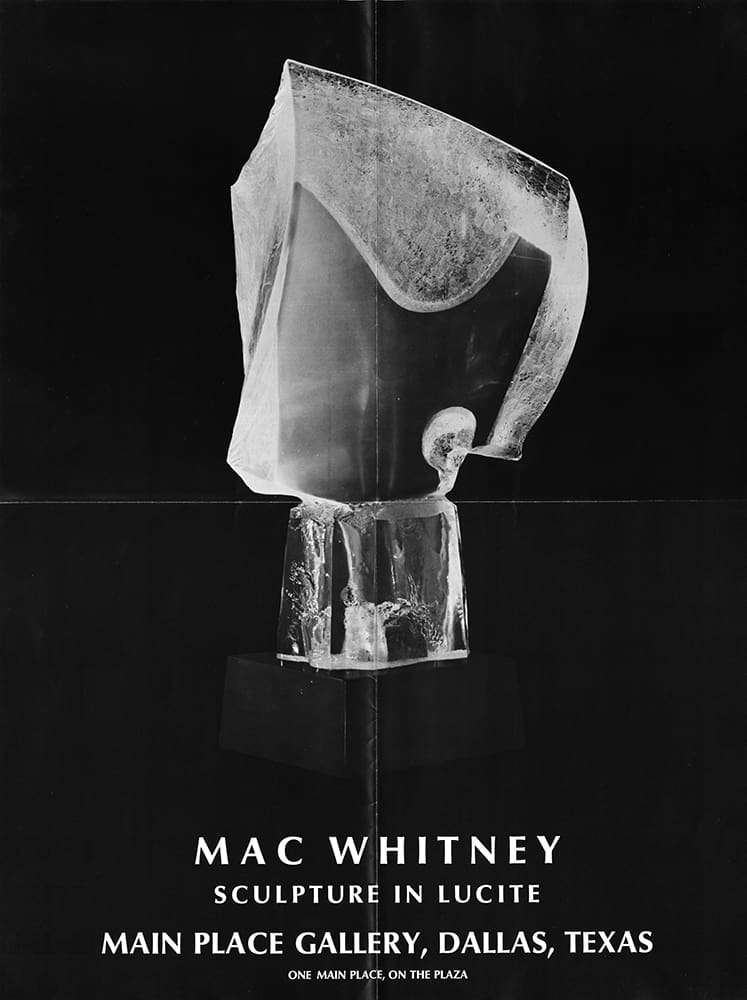

Earlier in his career, the Texas artist created diaphanous lucite sculptures, some of which were featured in his first solo exhibition at the One Main Place Gallery in Dallas back in 1969. Eugene Binder, owner of his eponymous gallery in Marfa, knew Whitney for many years. Binder had an affinity for Binder’s acrylic sculptures, and even worked as his full-time assistant for a few years.

“At that time, he was doing cast acrylic sculptures — and this was clear acrylic,” said Binder. “They were transparent and really quite beautiful and abstract. He placed these in collections around Dallas and in other cities.”

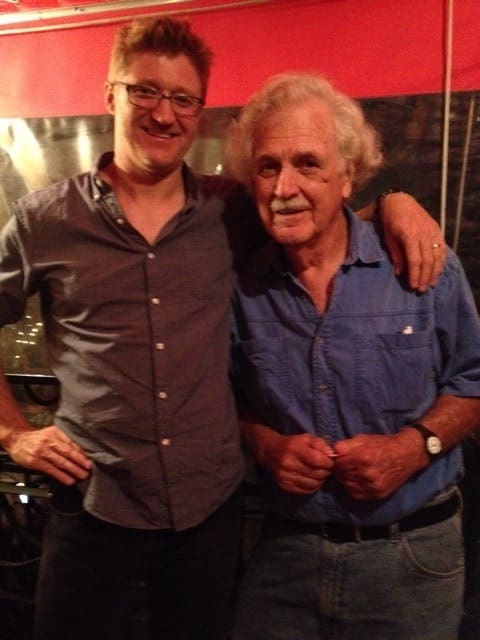

During what was likely one of his last trips to Houston, Whitney drove his truck around the city, showing Binder a boom crane located near The Ismaili Center Houston along Allen Parkway. The two friends also spent time at The Menil Collection.

For decades since the 1970s, Whitney lived and worked on a 22.5 acre parcel of land in Ovilla, Texas, 20 miles South of Dallas. Earlier in his career, he was associated with a group of artists known as the Oak Cliff Five, which also included George T. Green, Jack Mims, Jim Roche and Bob “Daddy-O” Wade. However, Whitney charted his own unique path away from the limitations of art movements and art history, becoming known as a solo artist.

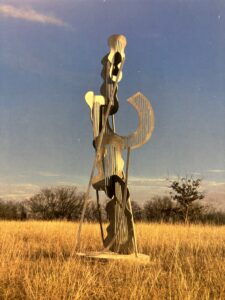

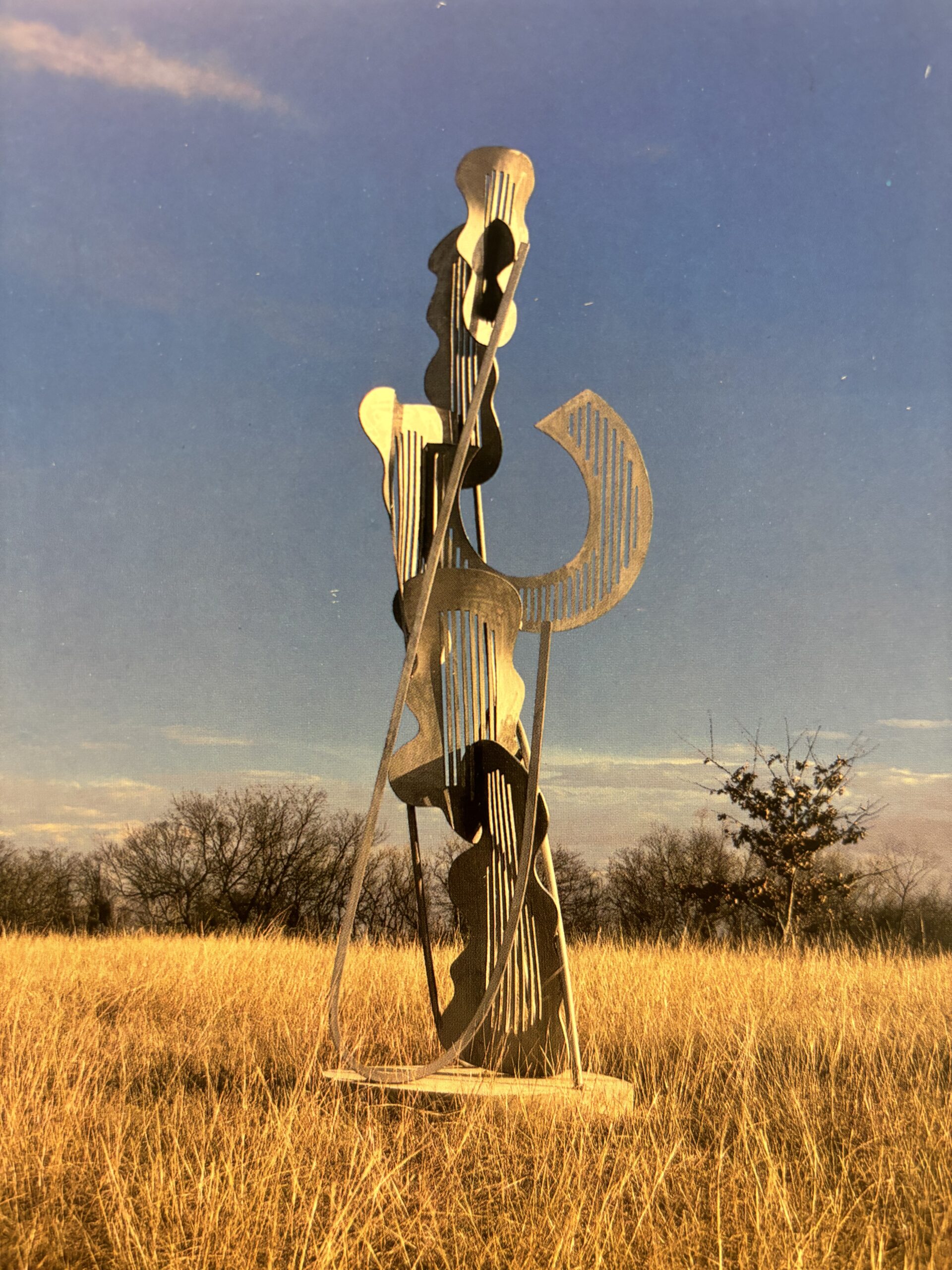

Writer Janet Kutner described Whitney’s process of working with steel as “intuitive.” Writing for a Harris Gallery solo exhibition catalogue focused on Whitney’s work in 1991, Kutner noted, “He has been juxtaposing curvilinear and angular elements since the mid-1970s.”

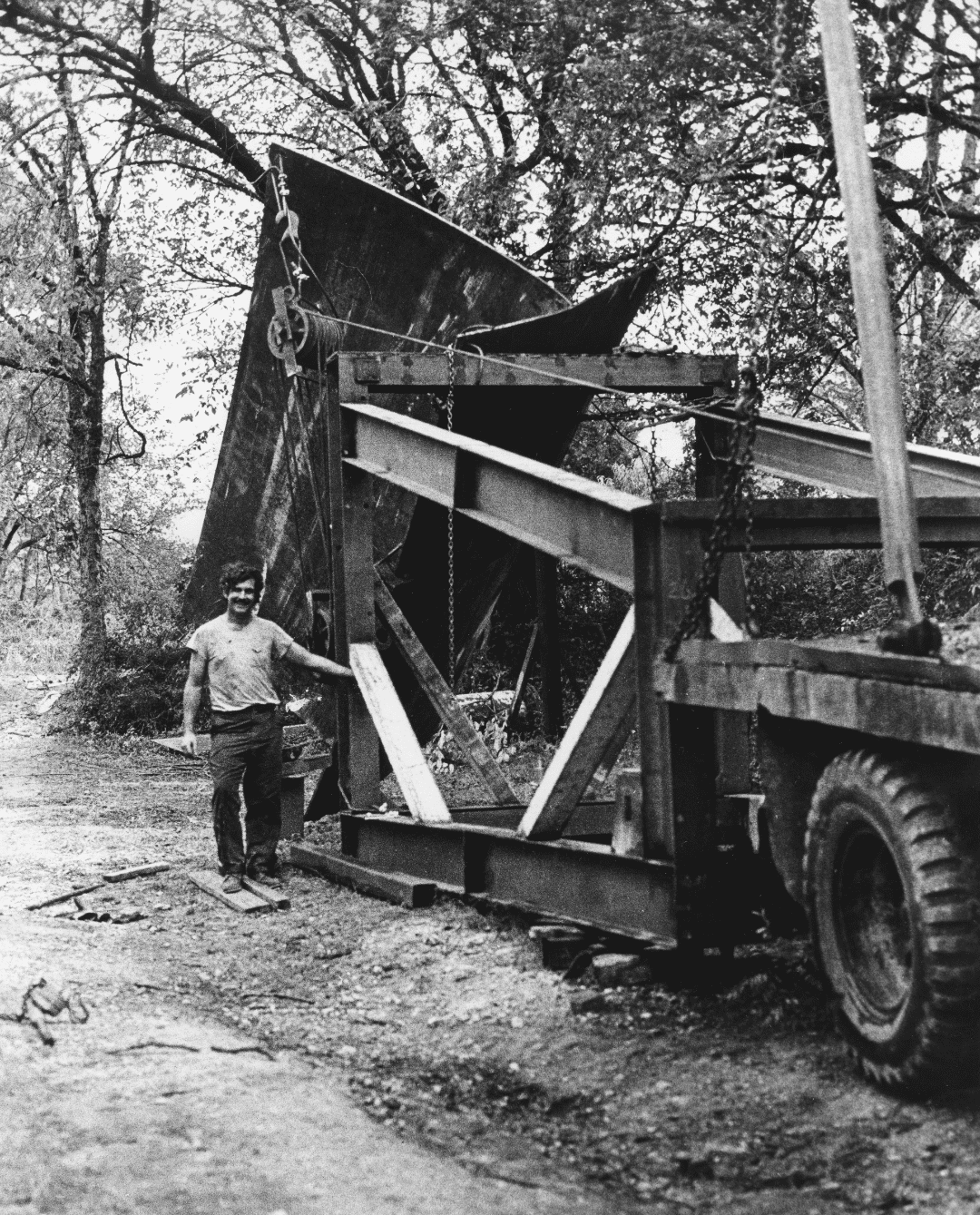

“Even his monumental sculptures look so buoyant that it’s easy to overlook the physical effort expended in building them,” said Kutner. “Simply warping the metal rod on which a piece sits can be an exhausting task, requiring Whitney to use winches mounted on two trucks, walking from one truck to another to pull the metal taut by huge cables.”

Speaking with PaperCity in December 2024, Whitney mentioned two artists who inspired him over the years. “Julio González, who worked with Picasso, made those great figurative pieces. And David Smith, who did all the great Agricola pieces, was a great influence.”

Born in Manhattan, Kansas in 1936 during The Great Depression, Whitney spent much time on the family farm, tending to wheat crops and Duroc hogs. As Whitney recalled, “I made cast acrylic pieces when I was in graduate school at the University of Kansas, finishing my Master of Fine Arts there.”

Whitney shared a notable interest in common with another legendary sculptor, John Chamberlain: a love of Texas, its lore, and small towns. Chamberlain’s Texas Pieces sculpture series featured humor-infused titles including Chili Terlingua, Falfurrias (Marshmellow), Glasscock-Notrees, Panna Normanna, Papalote Goliad and Barge Marfa. Chamberlain constructed these and other works at a ranch owned by collector Stanley Marsh in Amarillo, Texas during the years 1972-1975. In contrast, Mac Whitney’s sculptures typically have more straightforward but still Texas-centric titles: Pecos, Lavaca, Houston, Madero, Waco, Tascosa, Cuero and Tioga.

Commissioned in 1979 by the City of Houston and completed in 1981, Mac Whitney’s majestic, red abstract steel Houston sculpture stands 50 feet tall and weighs 50,000 pounds. Located in Stude Park near White Oak Bayou, Houston is visible from I-10 and Studewood, towering above most structures and the natural ecosystem within The Heights. As one walks around the base of the impressive structure, it almost appears as totally different sculptures while viewed from various angles.

In an essay written for the “Mac Whitney: Sculptures from the 1970s” exhibition at Kirk Hopper Fine Art in Dallas, Susie Kalil observed that Whitney’s “hands-on approach to metal makes poetry out of industry. Few sculptors have imbued raw steel with new life as magically as Whitney.”

Mac Whitney’s art is preserved in numerous collections, including the Dallas Museum of Art, The Fort Worth Museum of Art, The Art Museum of South Texas, The Nave Museum, The University of North Texas Museum and The Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas.

Here, PaperCity spoke with several Texas art luminaries about the legacy of Mac Whitney.

Sonja Roesch, Gallerist, Houston

Mac did a great job over his lifetime to produce all the different sculpture styles. In the beginning, he did experimental sculptures with resin and stainless steel. The Link series, the Underslung series, T-Angle, Kinetic pieces — all the different sculptures. Big 50-foot-tall ones to small tabletops, and everything in between.

Mac always went his own way. He was very independent and didn’t care what others did or thought. He just did what he liked to do. A very, very nice personality. We all admired him.

He didn’t care about what happened in the art world. He just did his thing without any drawings. The sculptures were constructed on the go. He had to have the engineering in his blood, in his genes, to make these huge sculptures that are really stable and perfectly engineered. He was a genius to me.

Andrew Durham, Gallerist, Houston

Mac Whitney was a remarkable inventor who embraced a casual, unhurried approach to his craft. With a unique talent for bending cold steel into graceful shapes, he operated as a one-man show. Living, working and traveling alone. Transporting his art by himself, Mac set his ways early on, and they served him well throughout the years. It was a privilege to know him, to witness his extraordinary process and to call him a friend.

John Clement, Sculptor, Brooklyn

It’s a bit inaccurate to call the field of sculpture a “profession.” Yes, there are methods and materials, business decisions and the like. But it’s not a true profession. It’s a calling; a belief in things that are not clear and present to others. Artists are unique with their own set of codes they live by; but sculptors, by and large, are even more so. It’s like wrestling and poetry combined. Highly physical, extremely intellectual, and sometimes plain dangerous.

There is so much that a sculptor needs to learn in their lifetime, and maybe less than 3 percent can be taught in a classroom. All the rest is learned by doing and living. Mac Whitney was a PhD in this. His innate knowledge of shape and form, methods, materials and colors were hard earned and timeless.

I was one of the fortunate who had a chance to know Mac and speak his language. I will be forever grateful for the opportunity.

Kirk Hopper, Gallerist, Dallas

I love Mac’s sculptures. It was the best of times when I would visit him. Each time, I would discover pieces that I hadn’t noticed on the last trip and marvel at what he was presently working on. I wish I could see his work all over the world.

Eugene Binder, Gallerist, Marfa

Mac moved into the downstairs space of a dilapidated building in Oak Cliff previously occupied by a painter who, at the first moment of achieving some success, had promptly moved out. I lived on the second floor and volunteered to help Mac move a large assortment of equipment, accumulated for making his work in the building. (The property on which the building stood had achieved some minor historical note a decade earlier when Lee Harvey Oswald shot and killed Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit on November 22, 1963.)

While moving Mac’s artmaking equipment into his downstairs studio, it became obvious that almost all of these items had been heavily used and extensively repaired. Some had been altered from their original intention to a specialized application in Mac’s artmaking practice.

Although Mac earned his MFA from the University of Kansas in 1968, his approach was more pragmatic than academic. “Get it done, no matter what,” could have been his credo. Much of our time was spent repairing things to make them somewhat functional before they could be used for making sculpture — from high-pressure autoclaves that he used to cast acrylic, to an 18-wheeler tractor trailer rig we somewhat rehabilitated to haul large-scale outdoor sculpture.

The last time I saw Mac was January at his place. He was telling my wife about us hauling a large welded steel outdoor sculpture to Houston. I was driving the truck we had attempted to make road-worthy, towing a twin-axle flatbed trailer that was mechanically as dubious as the truck, and overloaded with the components of the steel sculpture. As we approached the city at dusk, it began to rain with increasing intensity. I turned on the windshield wipers and the headlights immediately went out. Mac, seated on the passenger side of the cab, calmly said, “Well, Binder, you can either have functioning wipers or functioning headlights, but not both.”

Safety concerns did not often make Mac’s top ten priorities. It was perhaps on the edge of divine intervention, and a perceived but unspoken “higher calling of artmaking,” that we were both able to avoid being seriously injured assembling sculpture, disassembling it, loading, transporting, reassembling, and installing.

In subsequent years, Mac would periodically call me to talk about near-catastrophes he had experienced. Heavy steel cables pulled beyond tensile limits, breaking, and — in one instance — almost blinding him in one eye. A massive steel plate, hoisted a fraction over its tipping point and crashing down on the cab of a truck with Mac inside. To name a few.

While not consciously setting up a situation for equipment to fail, it was almost as if after it did fail, he seemed exhilarated that he had escaped from sustaining injury. He always wanted to talk about it with me, as I had first-hand experience working with Mac on how things could go while in the quest of getting it done; no matter what.

Find work by Mac Whitney at these Texas galleries: Kirk Hopper Fine Art, Dallas; Gallery Sonja Roesch and Andrew Durham Gallery, both in Houston. A video of Mac Whitney discussing his art practice is viewable here.