Two Groundbreaking Exhibitions at the Meadows Museum Bring the Art of Fashion to Life

Fashioning History

BY Lisa Collins Shaddock // 10.05.21Clockwise from left: Manuel Piña (Spanish, 1944–1994) [designer], Alex Serna [painter]; Vestido (Dress), 1991. Cellulose and cotton. Museo del Traje, Madrid; Peineta (Comb), c. 1890; Traje a “la francesa” (French Costume), casaca and chupa (Vest and Dress Coat) [detail], c. 1795–1800.

The Meadows Museum’s exhibition “Canvas & Silk: Historic Fashion from Madrid’s Museo del Traje” marks the first major collaboration between Madrid’s Museo del Traje, Centro de Investigación del Patrimonio Etnológico (the Spanish National Museum for Fashion), and an American museum, as well as the first time its collection of historic Spanish garments and accessories has been exhibited in the United States.

Rather than curating a standalone exhibition — something the Meadows often does (including its 2007 exhibition “Balenciaga and His Legacy: Haute Couture from the Texas Fashion Collection”) — Meadows Museum curator Amanda W. Dotseth saw the partnership as an opportunity to bring the figures portrayed in the works of the Meadows’ permanent collection to life. “I was really interested in trying to say something new about the permanent collection — to say something new about the works that our visitors already know and love, and to bring new energy to the collection,” she says.

When it was decided that the exhibition would inform the permanent collection, the games began. Dotseth and her exhibition co-curator, the Museo del Traje’s Elvira González, compared notes. “It was really fun because I would throw up an image, for example, of our painting by Ignacio Zuloaga [The Bullfighter “El Segovianito,” 1912], and she would say, ‘We have a traje de luces’ — which is what the traditional bullfighting costumes are called — ‘and it’s even the same color as the one in the painting.’”

Through this process, Dotseth learned something new about the works she knows so well. “Just the preliminary exercise of looking through the permanent collection with the sole idea that I was looking for elements of fashion … I learned a lot, just looking at the collection with a different eye,” she says. “But then once I talked to [the team at Museo del Traje], it was a whole new level of knowledge.”

One theme that emerges through the exhibition is the adoption of indigenous dress by the aristocratic classes to symbolize or assert national identity or national exceptionalism. The collection includes two portraits of duchesses who are wearing items that are traditionally associated with Spain but, according to Dotseth, were appropriated or “borrowed” from working-class women and presented in an elevated fashion — which, at the time, meant doing as the French do.

“We have a portrait of the Duchess of Medinaceli, and in her portrait, she has chosen to wear a short bolero jacket and a red skirt with black ball fringe, which are emphatically not derived from French fashion and are very much derived from Spanish regional dress,” Dotseth says. “But, then again, she’s still wearing her corset, she still has her crinoline under her skirt, so the silhouette is still appropriate for what was known as ‘dressing in the French style’ — but she’s changed it up with her bolero jacket and ball skirt to kind of assert Spanish-ness.”

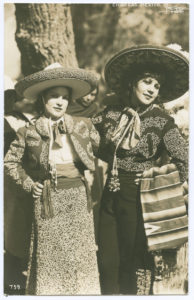

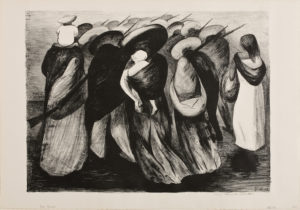

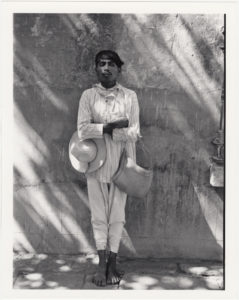

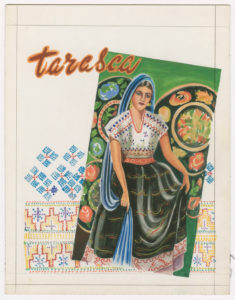

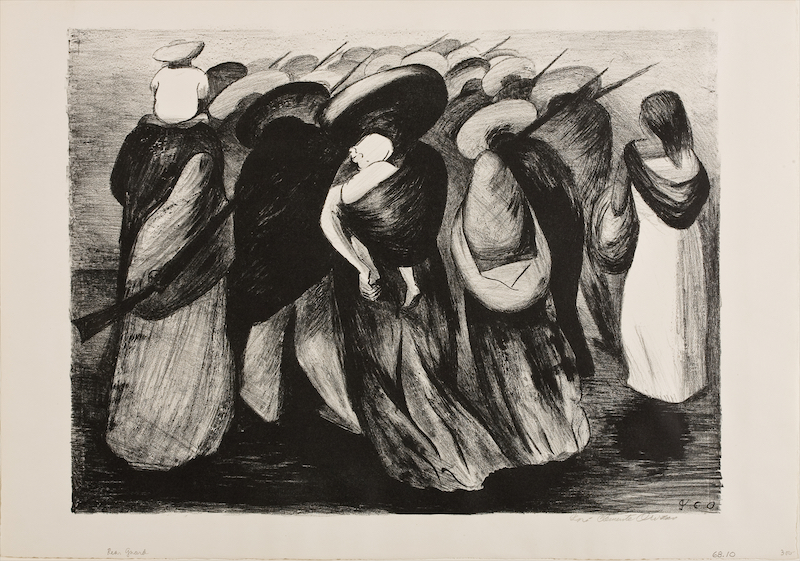

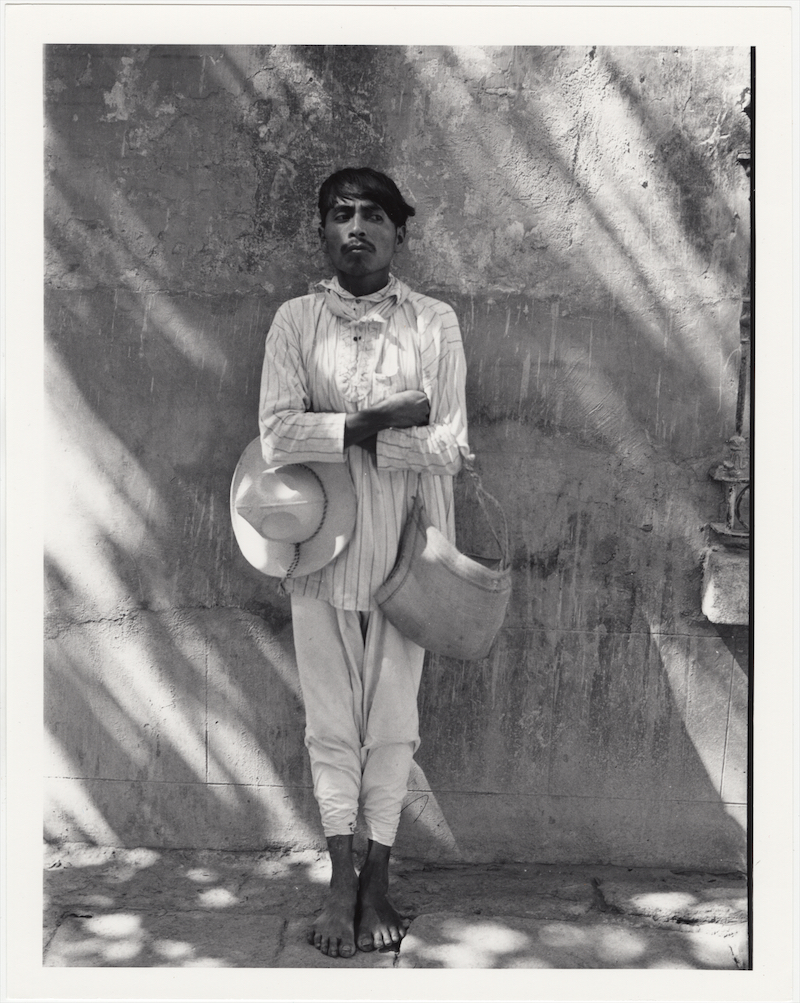

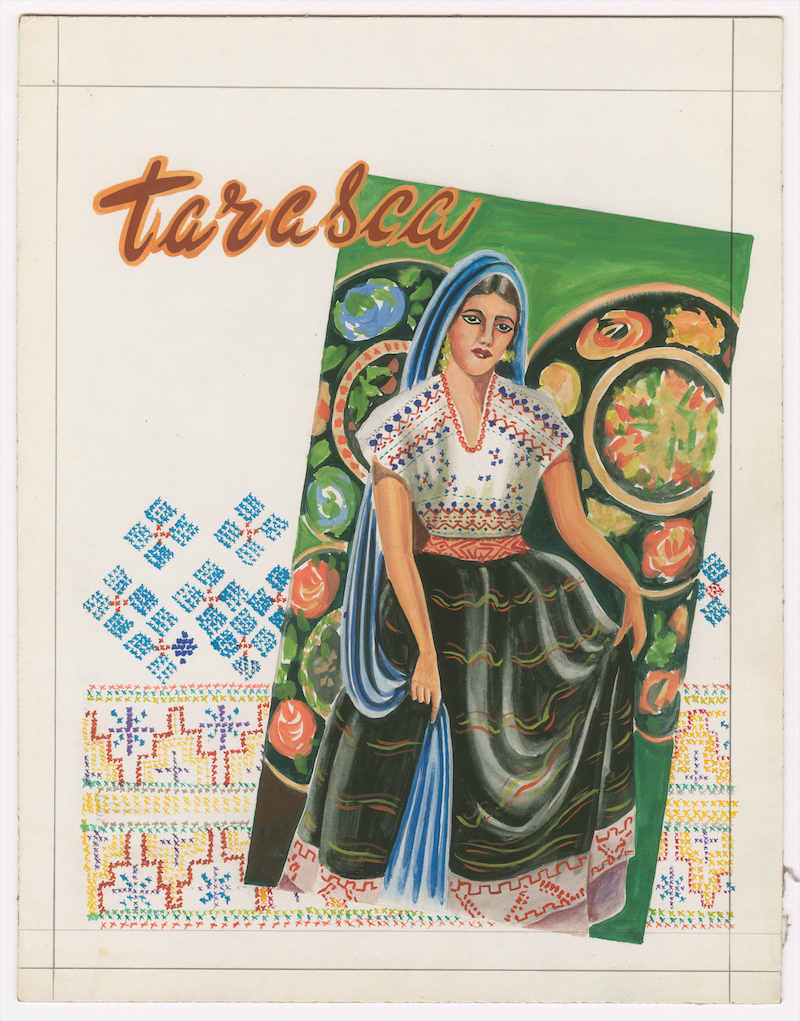

The Meadows’s concurrent exhibition, “Image & Identity: Mexican Fashion in the Modern Period,” curated by Akemi Luisa Herráez Vossbrink, the Center for Spain in America (CSA) Curatorial Fellow at the Meadows Museum, features photographs, prints, books, and gouaches from the 19th and 20th centuries and builds on this theme of national identity and how its formation is often accompanied by a resurgence in the popularity of indigenous dress.

A famous example is Frida Kahlo’s “deliberate appropriation” of indigenous dress despite not being of indigenous heritage, Dotseth says. “She emphasized this kind of dress as evidence of her Mexican-ness. It’s a similar process that happens at two different times, but they parallel each other in the way that dress is used to assert national identity. It’s also about national exceptionalism because you’re saying this is what makes me Mexican, or this is what makes me Spanish. It’s still happening today, of course.”

Something else that still happens today is the art of accessorizing. “Canvas & Silk” is divided into themes, including “Stepping Out,” which Dotseth calls “the classic trope of the Flâneur — strolling the street to see who is out there and, also, to be seen. It’s not only about dressing a certain way but having the right accessories. The hat. The gloves. They all convey information about you. Your wealth, your social standing. Not only those things but also your marital status … I was careful to include not just garments but accessories because I am making an argument that they are often as key to accommodating social norms as the garments themselves.” It seems some things truly never change.

Canvas & Silk: Historic Fashion from Madrid’s Museo del Traje and Image & Identity: Mexican Fashion in the Modern Period, both on view at the Meadows Museum through January 9, 2022.

![Clockwise from left: Manuel Piña (Spanish, 1944–1994) [designer], Alex Serna [painter]; Vestido (Dress), 1991. Cellulose and cotton. Museo del Traje, Madrid; Peineta (Comb), c. 1890; Traje a “la francesa” (French Costume), casaca and chupa (Vest and Dress Coat) [detail], c. 1795–1800.](/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/meadows-museum-exhibit-1024x794.png)

![Manuel Piña (Spanish, 1944–1994) [designer], Alex Serna [painter]; Vestido (Dress), 1991.](/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/064-MTFCE092707_R-569x1024.jpg)

![Manuel Piña (Spanish, 1944–1994) [designer], Alex Serna [painter]; Zapatos (Shoes), 1991. (Photo by David Serrano Pascual)](/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MTFCE092708_R.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpeg)