Picturing Nature at MFAH — New Exhibition That Started With a Single Painting Gives British Landscapes Their Due

A Texas Family Legacy Of Intellectual Curiosity and Generosity

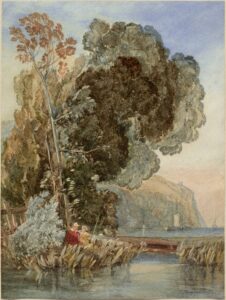

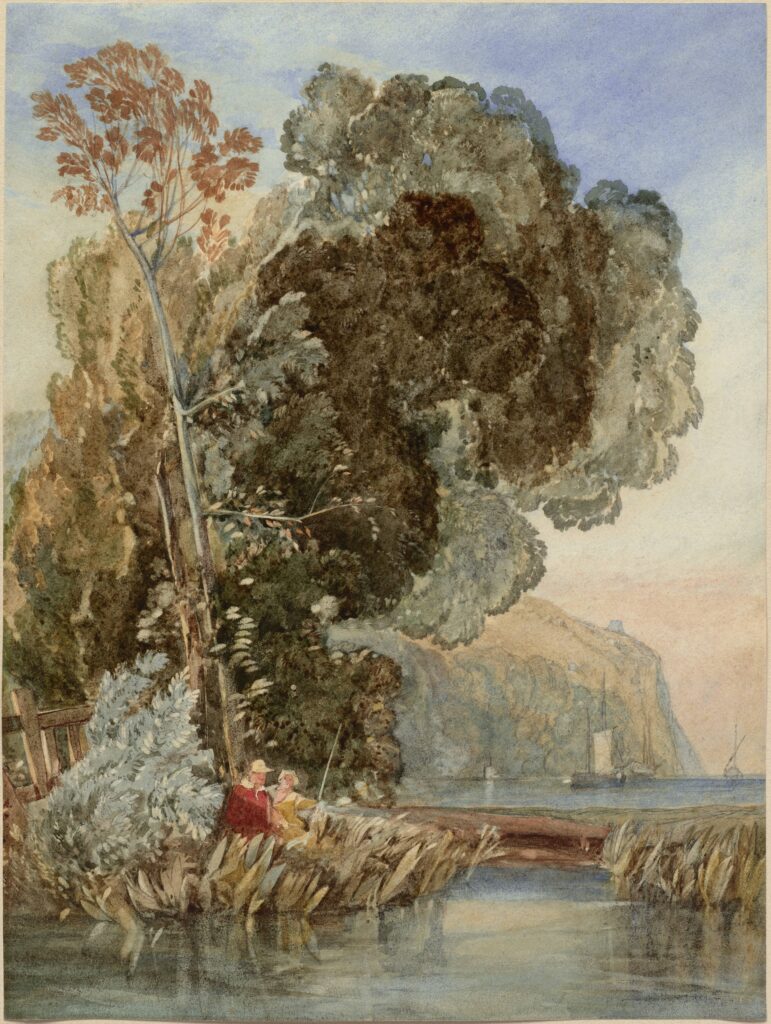

BY Leslie Loddeke // 01.29.25John Sell Cotman, “The Anglers (in Avon Gorge),” c.1829-30, watercolor over graphite, heightened with gouache and stopping out on wove paper, the MFAH, the Stuart Collection, museum purchase funded by Francita Stuart Koelsch Ulmer in honor of Nancy Stallworth Thomas, and Kim and Sellers Thomas. (Image courtesy MFAH.)

A Houston woman inherited a painting from her grandmother which has became the inspiration for an entire collection of outstanding 18th and 19th century British landscapes now on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

“Picturing Nature: The Stuart Collection of 18th and 19th century British Landscapes and Beyond” consists of more than 70 watercolors, drawings, prints and oil sketches from John Constable, Joseph Mallord William Turner, Thomas Gainsborough and other stellar artists whose work exemplifies the flowering of landscape drawing.

This Houston exhibition tracks the rise of the landscape genre in Britain and its influence beyond, notably in France, as seen in works by Eugene Delacroix and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

The initiation of this collection, displayed in a scholarly exhibition on the upper floor of the Beck Building, serves as the introduction to a charming story. It speaks of a Texas family legacy of intellectual curiosity and generosity with ties to the MFAH since the museum was first formed in 1900.

The landscapes in the current exhibition were acquired by the MFAH in 2015 when Houstonian Francita Stuart Koelsch Ulmer established the Stuart Collection in memory of her parents Robert Cummins Stuart and Frances Wells Stuart. Her interest in British landscape was piqued when she inherited an oil sketch by John Constable, “A View on the Banks of the River Stour at Flatford” (1809-16), from her grandmother.

Her grandmother’s Constable can now be seen in the context of a pivotal moment in the history of European painting, as MFAH director Gary Tinterow notes in the exhibition catalogue. MFAH only a comparatively small number of British landscapes before Dena Woodall, curator of prints and drawings, worked with Ulmer to build this impressive collection over the past 10 years.

The exhibition illustrates how, during the 18th and 19th centuries, artists moved from topographical and pictorial depictions of the landscape in the prevailing classical style to personal, emotionally expressive treatments of nature that reflected the Romantic poetry of the period.

During this transformative era, British artists innovated the watercolor technique and elevated its status as an art form. So much so that the mid-18th to the mid-19th century became known as Britain’s Golden Age of Watercolor.

As British art scholar Anne Lyles wrote in the catalogue, in the early 1800s, when most British landscape painters were painting idealized landscapes in the manner of Old Masters such as Claude Lorrain, Constable (1776-1837) decided to paint the scenes he loved in his native Suffolk as naturalistically as possible. Rather than “running after pictures and seeking the truth at second hand,” in other words, perfecting his art by copying from the Old Masters, he began to work directly in front of his subjects in the open air.

“Nature is the fountain’s head, the source from whence all originality must spring,” Constable asserted in a letter to a friend.

Constable painted nature as it was seen, incorporating the momentary effects of light and weather. His oil sketch of the River Stour shows how carefully and yet quickly he depicted a passing rainstorm. Later, Constable’s watercolor “Illustration to Stanza V of Gray’s Elegy” (1833) was among several illustrations he provided for John Martin’s edition of Thomas Gray’s popular “Elegy Written in a Country Church Yard,” aptly picturing the lonely scene.

In contrast, other British landscape artists like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) captured nature as it was experienced and felt, an increasingly appealing mode. Especially in his watercolors, Turner became recognized for his expressive use of light. This is seen in his dramatic 1798 watercolor “Bridgnorth on the River Severn (Shropshire),” a magnificent distant view of a village church atop a hill under a pale, expansive sky.

“Turner’s 250th birthday is celebrated in 2025, and still he enthralls. His paintings have become part of British national identity, passing from art to popular culture,” The Financial Times chief visual arts critic Jackie Wullschlager declares in a recent article listing the multiple museums presenting Turner exhibitions this year (including Tate Britain’s “Turner and Constable”).

Although Turner’s idol was 17th century painter Claude Lorrain, he belongs to romanticism’s disorder, Wullschlager writes in a masterful analysis of Turner’s enduring popularity. “Smashing Claude’s classical equilibrium, he created pictures for a churning industrializing age, uncertain of its relationship with the natural world, thus fixated on landscape in painting and poetry,” she writes, noting that Turner’s peers were Constable and the Romantic poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth.

Picturing Nature With Words and Artifacts

Indeed, the landscapes in this MFAH show may well evoke for some viewers school-age memories of learning Wordsworth’s poem“Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” In a tribute to nature, the poet vividly describes his childhood delight in “Fountains, Meadows, Hills and Groves.” As an adult, he philosophically realizes that while “nothing can bring back the hour Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower, We will grieve not, rather find Strength in what remains behind.”

“Finding strength in what remains behind” must have become especially important at a time when, as curator Woodall pointed out in the catalogue, society “witnessed rapid industrialization and the emergence of a middle class that sought refuge in rural settings.” She cited John Sell Cotman’s colorful ‘The Anglers (in Avon Gorge),” (c. 1829-30), which depicts a couple fishing among reeds, set against a towering backdrop of billowing trees.

Don’t miss the array of period items, such as a mid-19th century wooden Winsor & Newton watercolor box, that helped these enterprising artists picture nature. Especially helpful to the viewer are the cogent, well-researched descriptions in the labels that facilitate the understanding of each work of art.

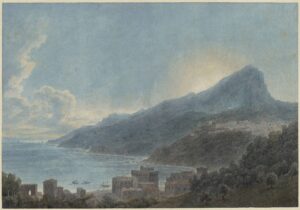

At the end of this MFAH “Picturing Nature” exhibition, take a moment to accept the invitation posted near the video monitor to see how scenes depicted in the exhibition look today. John Robert Cozens’ sumptuous watercolor “View of Vietri and Raito, Italy,” c. 1783, is among those in this creative presentation.

Catalogue contributor Kim Sloan wrote that this romantic view of a sunset on the Amalfi coast was among a group of watercolors that an affluent young man named William Beckford had commissioned Cozens to commemorate his Italian journey in 1782. Both Cozens and Beckford had been to Italy before. Beckford’s previous trip to Italy came during his 1780 Grand Tour of Europe.

The Grand Tour was a 17th to early 19th century custom in which young men of the British elite extended their formal education by taking a cultural tour through Europe, particularly France and Italy, sometimes sponsoring artists who were interested in expanding their own horizons and clientele. Several illustrations of the benefits of the practice are included in this comprehensive exhibition, of which Grandmother surely would have been proud.

‘Picturing Nature’ is on view through July 6 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Get more information here.

_md.jpg)