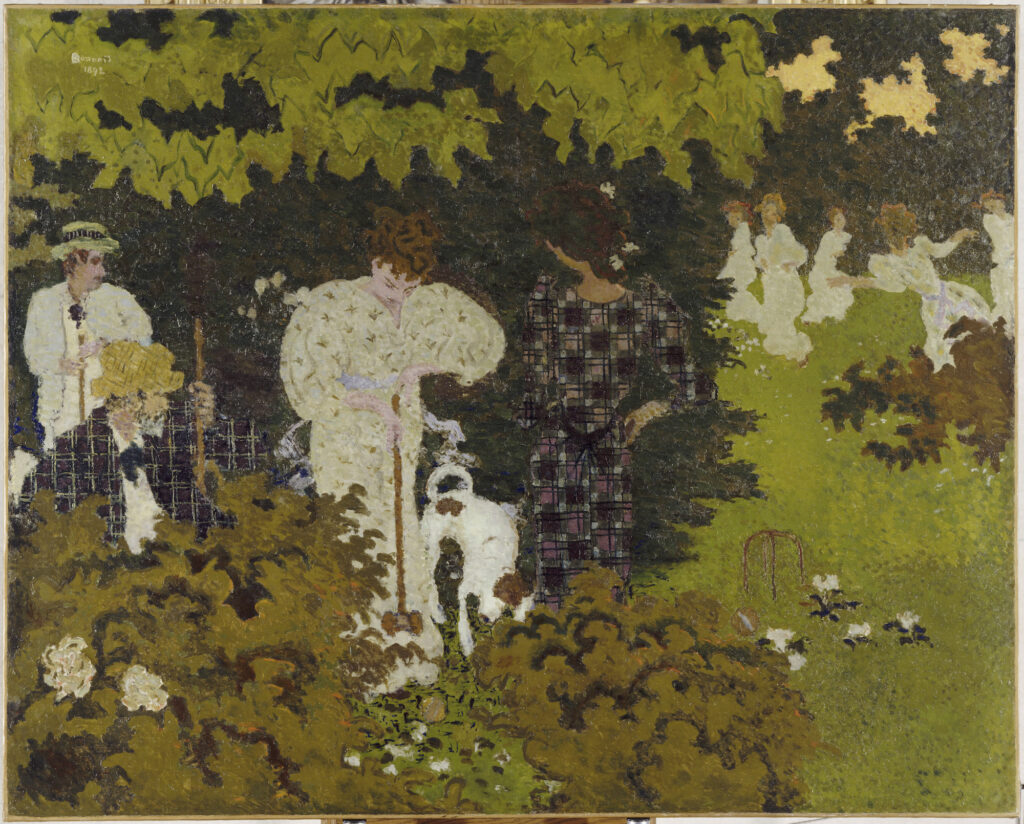

Pierre Bonnard’s "Twilight (The Game of Croquet)," 1892 (Paris, Musée d’Orsay © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Light, color, canvas: PaperCity queries Kimbell Art Museum deputy director George Shackelford in the final weeks of his curatorial triumph — the museum’s blockbuster exhibitions “Bonnard’s Worlds.” Lauded as one of fall’s 12 must-see museum shows in the U.S. by artnet.com, it’s the first look at Post-Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard (1867 – 1947) in nearly 40 years, Shackelford divulges his top three among the 70 breathtaking canvases debuting in Fort Worth before traveling to co-organizing museum The Phillips Collection in March.

Wade Wilson: In your introduction to the Pierre Bonnard exhibition catalog, you write: “Bonnard’s work, without any desire to be autobiographical, nonetheless both chronicles and exposes his life, because almost every work of art he ever made was in large part inspired by the world in which he lived, and by his place in that world.” Please expand on this observation.

George Shackelford: Bonnard talks from time to time about the “idea” for a work of art, which is what he’s seeking to make real when he faces a blank canvas. The idea comes from something around him, typically — his wife and one of their dachshunds across the table, say — and it sticks. Once the idea is there, a certain amount of thinking ensues, and often he’s thinking with a pencil. With an idea in mind, he may make some sketches on pages in his diary, or on a scrap of paper, just to “practice” the composition that is taking shape. All of this is brain work, but I suspect that a lot of it is intuitive. People describe him painting more than one picture at a time — all tacked to the same wall — so a lot of inspiration is momentary. The idea, though, must be there for the process to begin.

WW: Why does your take on Bonnard venture into the emotive and psychological, rather than following the typical curatorial vision of arranging works in chronological order?

GS: When the Kimbell acquired the great Landscape at Le Cannet (1928) in 2018, I was researching the painting’s history and the circumstances of its creation and was surprised to find that it was a commission for a particular spot in a particular patron’s house. I was intrigued by the fact that Bonnard was painting a composition that is so much about himself not for himself, but for it to be on display in the home of somebody else. That got me thinking about the freedom with which he gave the outside world very incisive glimpses into his own world. Beginning in that vein, I imagined arranging an exhibition in a way that might be illuminating in different ways than the usual monographic show can be. I will be very interested to see how the paintings hang together. The loans we have been granted are extraordinary.

WW: What impact do you anticipate for your audiences as they respond to these subtle yet intoxicating paintings?

GS: Again and again in Bonnard’s paintings, he invites us to look hard and to see what it is that he has done to transcribe the idea into the finished work. A lot of times he gives us clues as to where we’re supposed to focus our attention — like putting a little dog right on the edge of a table with a tablecloth that points straight at him. Or he’ll consign something that’s really important to the edge of a composition, where you might miss it if you didn’t pay attention. This show will be full of those opportunities. I hope it’s one that people will want to see more than once.

WW: On light and color in these evocative canvases.

GS: Many of Bonnard’s paintings are about the action of light. Light coming in a window, for instance, or the glare of an electric light bulb. Color and composition are the elements with which he conveys that action, and they’re critical. Light can start out yellow and turn blue as it moves into a room, or a garish light fixture can make the inside of a cupboard glow blood red. When Bonnard saw something like that happening, he seized it. He might make a quick note of it, just as a reminder. But then the challenge came, using color and composition to convey the emotion that went along with the idea. It could be wonder; it could be affection; it could be mourning. In the end, I don’t think it matters whether we feel the same thing Bonnard did, as long as we open ourselves up to feel.

WW: Is there a particular work or works among the paintings you have selected for the exhibition that you consider most important?

GS: I am particularly thrilled that we’ve been able to bring the three great late bathers, painted between about 1936 and 1946, together in the States for the first time in 25 years. One is in Paris, one is in Pittsburgh, and the third is in a private collection. There was a time six months ago when I thought none of them might come. To get all three is nothing short of amazing.

WW: There have been theories that Bonnard influenced Rothko. Could you expand on this thought? Which modern and contemporary painters may have looked at Bonnard’s work or found inspiration in his painting?

GS: The impact that Bonnard had on American painting is a fascinating subject. The answer is that we don’t really know who was impressed by what and when — at least I haven’t found documentation about it. What we can say is that the MoMA/Cleveland retrospective held the year after Bonnard’s death [1948] was a superb exhibition — many of the paintings in our show were there — and it was the first occasion that many painters of the post-war period would have had to see Bonnard’s work in depth. And there’s no way to go into a room full of Bonnards and not have strong feelings about them.

So, I think a painter like Rothko, who was already so attuned to color, couldn’t have seen the show without learning something from it. I feel the same way about the relationship between Bonnard’s compositions and those of Richard Diebenkorn. And with so many great paintings by Bonnard in Washington at The Phillips Collection, there’s a good chance that they were important for the Washington color-field painters — Morris Louis, Sam Gilliam, Alma Thomas, and the early Kenneth Noland. Speaking of The Phillips Collection, we know that Rothko went there to see how Duncan Phillips had made a room entirely devoted to Rothko. He is bound to have been happy that his works were being given the same reverence that Bonnard’s were.

“Bonnard’s Worlds,” is on view through January 28, 2024, at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. More information here.