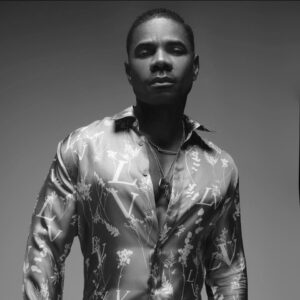

Grammy Award Winner and Fort Worth Native Kirk Franklin Shares The Story Behind His New Album Father’s Day

An Exclusive Interview With The Gospel Singer Ahead of His North Texas Show

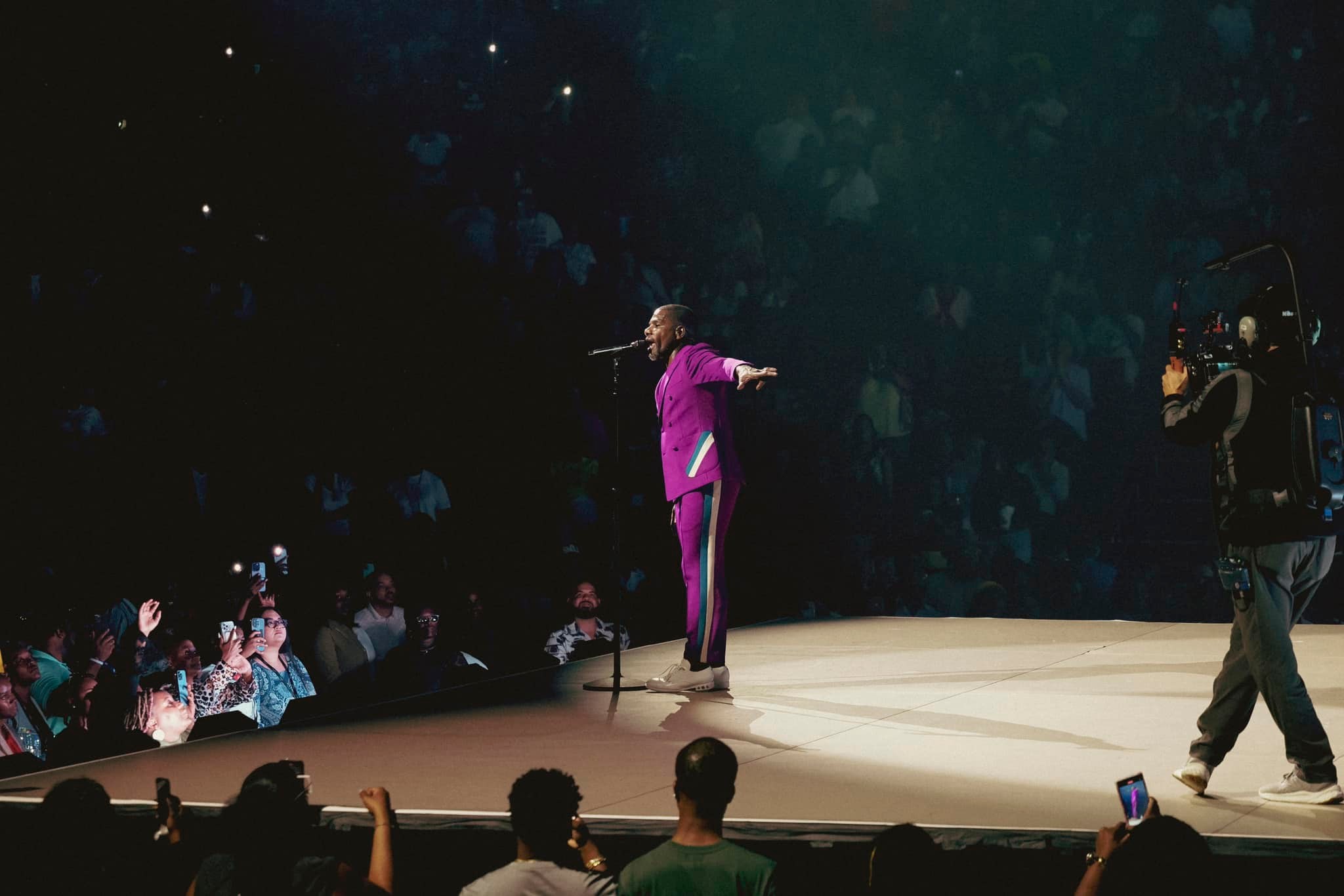

BY Courtney Dabney // 04.15.24Kirk Franklin returns to North Texas for his fourth annual Exodus Music and Arts Festival this May.

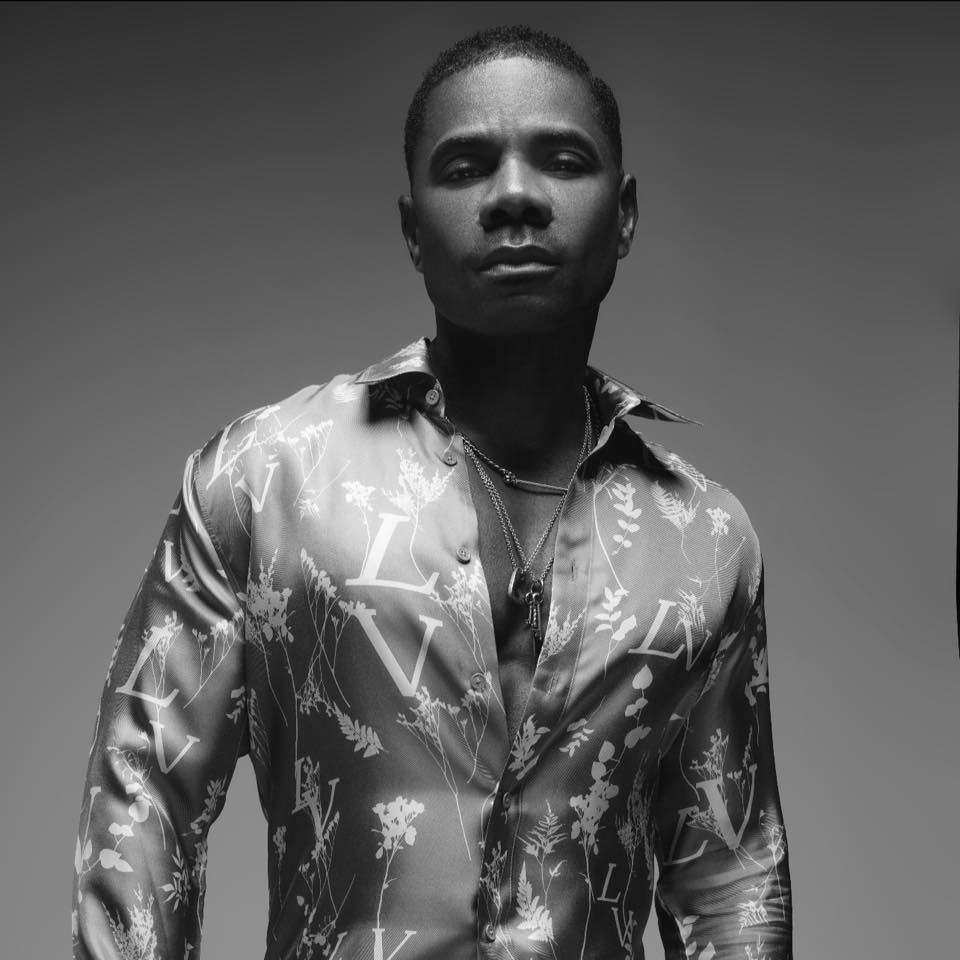

Kirk Franklin is one of the best-selling and most-awarded gospel recording artists of all time. His self-titled first album Kirk Franklin & The Family (1993) went platinum, and most of his subsequent offerings have likewise become gold and platinum sellers. As for Grammy awards ― of his 31 nominations so far, Franklin has won 19 Grammy’s during his 31-year career. His range flows effortlessly into hip-hop and rhythm and blues.

Local fans can take part in the fourth annual Exodus Music and Arts Festival which is returning to Irving’s Toyota Music Factory on Saturday, May 25, and Sunday, May 26. The festival is produced in conjunction with Live Nation and tickets are on sale now.

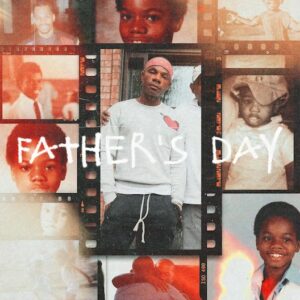

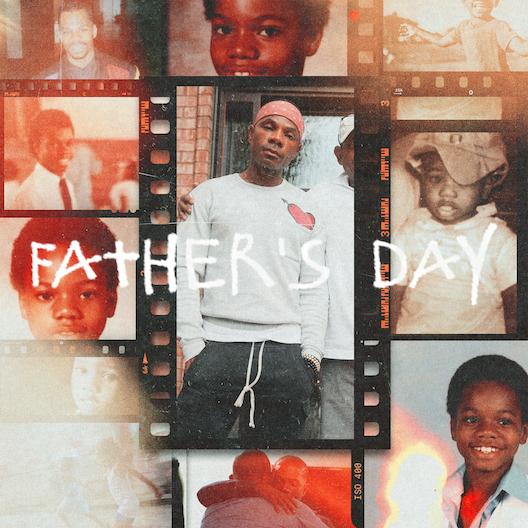

His 13th studio album, Father’s Day, was recorded at Franklin’s $2 million, state-of-the-art Fo Yo Soul recording studio located in downtown Arlington, and released by Fo Yo Soul/RCA in October of 2023. But, it was a paternity test that rocked Kirk Franklin’s world last year ― forcing him to revisit the sadness from his troubled childhood.

“The record had another title and a completely different direction,” Kirk Franklin tells PaperCity Fort Worth. “At 53, I wasn’t looking for a father, and I was dealing with a mother that I had successfully kept at bay for 23 years.”

The musician unfolds the chaotic series of events and the very personal revelations that coincided with the making of his newest album in a 35-minute documentary called Father’s Day: A Kirk Franklin Story, which was released last September.

He tells PaperCity why truth is so powerful, and how music has always been his safe space.

Kirk Franklin Revisits His Riverside Roots

In some ways, it’s a uniquely Fort Worth story, of a boy growing up in the deprived neighborhood of Riverside. A neighborhood where Franklin agrees that “not much has changed over the past 50 years in Fort Worth ― except perhaps for gentrification, which doesn’t improve the experience or outcomes of those who live there.”

But it’s also such a common story about a young man’s search for his father, his identity, true belonging, and approval, that it transcends race or geography. And of course, as a musician, Franklin worked his way through the tidal wave of emotions in song.

“When I started to tease the documentary, we weren’t prepared for the response,” he says. “On the one hand, so many were very touched by it, but on the other hand, people who had experienced similar things didn’t understand why I needed to find my father. They thought Kirk Franklin has millions, he’s fine. Why does he care about knowing who his father is?”

“It’s really the story of marginalized communities who have simply become numb to it. People are stuck living in their own trauma. Fatherlessness has become generational. Ever since black people set foot on these shores, slavery tore family bonds apart. We’re still living with those repercussions.”

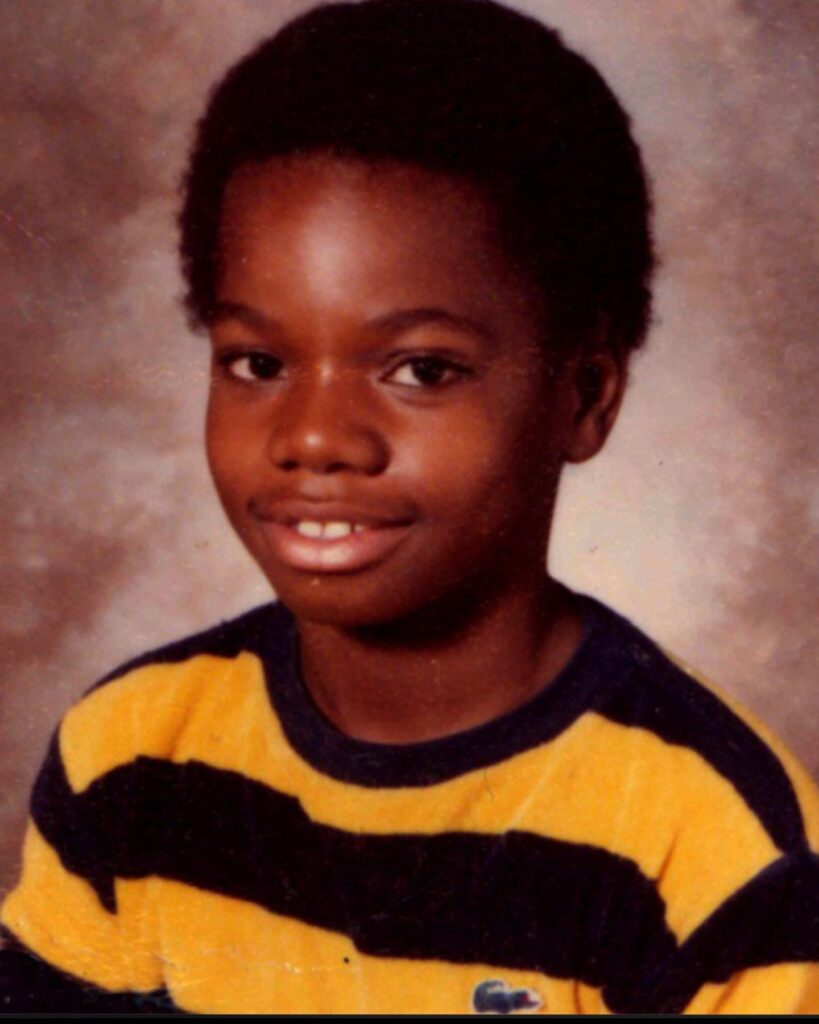

As for rehearsing the pain from his traumatic childhood ― where he was abandoned, lied to, desperately lonely, physically bullied, and hungry ― he just can’t go there. It’s simply too triggering and anxiety-inducing. So, our conversation quickly pivoted back to safer ground.

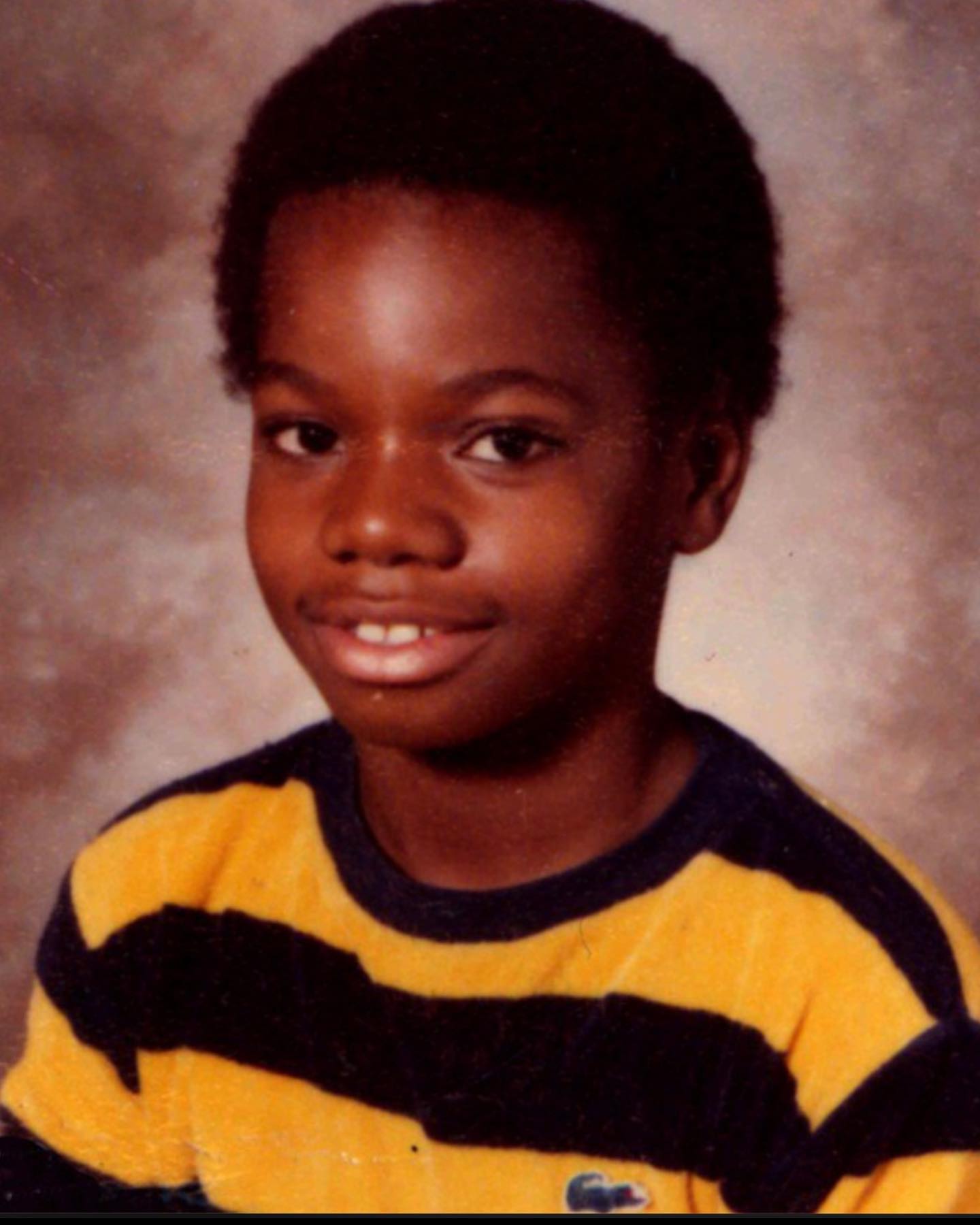

The Fort Worth native was born Kirk Smith in 1970 to a teenage mother. By the time he was four, the singer had been abandoned and left in the care of his great-aunt. When Gertrude Franklin adopted him, she gave him his (now famous) last name.

“When I was a little boy, I spent a lot of time alone and at the piano,” Franklin says. He routinely climbed up on the roof ― looking to the heavens, longing for a daddy and begging for answers that wouldn’t come for another fifty years.

The album is bookended by the songs Welcome Home and Somebody’s Son. The theme of what home means, and finding where you belong and who you belong to are at its core.

Father’s Day

Finding out, by happenstance, that his biological father was a completely different man than was told to him, and getting DNA confirmation of his identity (verified by not one, but two DNA tests) opened up old wounds, for this middle-aged recording artist, who is himself, a father and grandfather.

The camera crew that was there to film the making of the album, then shifted its attention to capturing the chaotic story as it was unfolding in real-time.

In the documentary, Franklin even shared the long-lost identity of his birth father with his own estranged son Kerrion. In it, he’s honest about the struggle of that broken relationship. When I asked him about the crossroads where he currently finds himself ― about restoring his own family, about taking a broken past and forging a new legacy, Franklin was once again at a loss for words.

“It’s difficult,” he says finally. “There is no sermon and there’s no pill that can transform me. I am still that broken little boy without a daddy.”

“I did the best I could. My life was sinking and I was underwater. I was a single dad at age 17, facing attacks and rejection both in the church and in my community.”

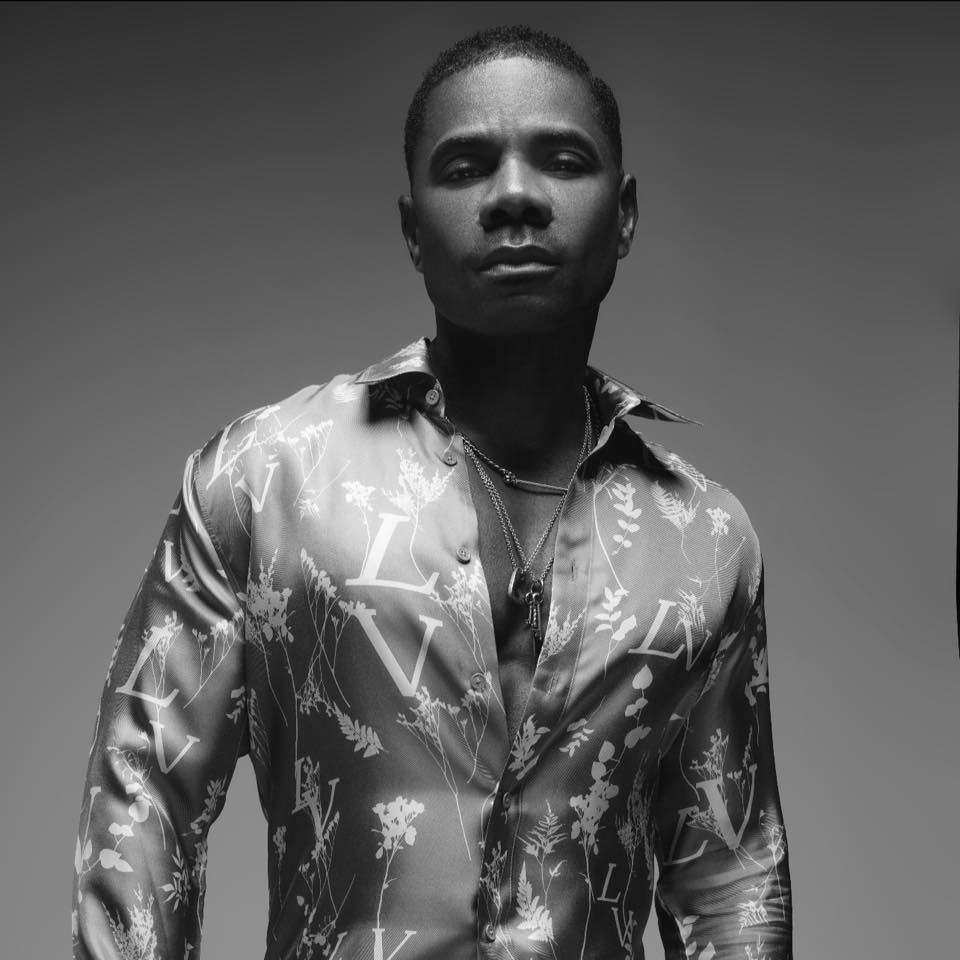

But, the hope of restoring relationships is ever present in his music, and the man who says he found love for the first time through performance, is no longer resting on his achievements and awards, nor is he living for the applause.

It’s a work in progress. He’s in the midst of it. As Franklin echoes in the documentary, “Who am I? I’ve only known me broken.”

The Duality of Reality

“In the song Welcome Home, it has the line, the duality of reality,” explains Franklin. “That’s the painful truth of our existence on this planet. A lot of things don’t make sense, and bad things happen to good people.”

While the intricate harmonies of a gospel choir are often rousing, Father’s Day is not only filled with those electric vocal performances, it’s often contemplative, a single voice, shredding the silence ― mirroring the full range of emotions that Kirk Franklin has rolled through this past year. Finally coming face to face with his birth father, and reconciling the fact that the man he thought he had every right to hate his whole life ― never even knew he had a son.

How different things could have been if the truth had come sooner for both of them.

“My music has always had a duplicity,” he says. “It’s always been transparent about questioning God. That’s the secret, back closet, stuff. The praise and worship music is only a trailer to entice listeners to go deeper. There’s a pendulum that swings back and forth, every moment of the day.”

As for the rapid decline of faith and church-going in America, Franklin says, “I think it’s the duplicity and the hypocrisy of American pulpits, not addressing the obvious injustice and pain, that has accelerated the decline in our churches.”

“The sad part of our journey as black and brown people is that poor communities still lack opportunities ― both educational and economic. That injustice can’t be overlooked.”

“The Christian message can’t be hyperbolic,” he continues. “I can’t just do music that’s pie-in-the-sky. I have to do music that challenges and questions. That’s how you bring back authenticity to the message.”

On his album Father’s Day, Kirk Franklin takes listeners to church Again (track 8) and Again & Again (track 9), because healing is a process for him, and hope is a place you should revisit often.

Franklin’s upcoming Exodus Music and Arts Festival plans to keep its message authentic as well ― leaning into the real-life struggles facing his fans.

_md.jpeg)