The Otherworldly Architectural Masterwork of Javier Senosiain and His Casa Orgánica

Northwest of Mexico City, The Singular House Was Designed By The Architect As His Own Residence

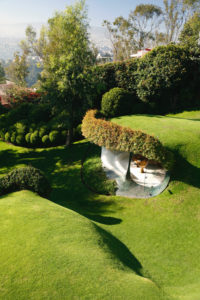

BY Robert Morris, With Catherine D. Anspon // 02.01.23Casa Orgánica is shaped like a tiburón (shark). (Photo by Pia Riverola and Arquitectura Orgánica)

Northwest of Mexico City, a sinuous and singular house was designed by architect Javier Senosiain in 1984 as his own residence. Twenty-seven years later, Casa Orgánica remains a touchstone for Senosiain’s unorthodox, highly original practice, as well as an emblem of the organic school of architecture. This masterwork, known mostly to a small coterie of devotees of 20th- century architecture, shares company with structures on the definitive international roster of Iconic Houses, by such luminaries as Frank Floyd Wright, Charles and Ray Eames, Albert Frey, Alvar Aalto, Oscar Niemeyer, Luis Barragán, Antoni Gaudí, Le Corbusier, Eliel Saarinen, Richard Neutra, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Javier Senosiain was born in Mexico City in 1948 and professes the organic concept of design which seeks harmony between humans and nature. This philosophy takes the synthetic manmade forms of building and integrates them into the surrounding world with an emphasis on a respectful conversation with nature. After studying at several schools and universities, Senosiain graduated from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City (1972), where he has taught the Design Workshop and Architecture Theory class for the past half-century. Concurrently he maintains a modest private practice, Arquitectura Orgánica, for which he’s garnered a cult following in Mexico for its visionary stance via private homes and apartment complexes, all colorfully painted, many of them tile- or stained-glass encrusted. These include structures as remarkable as they are unforgettable: La Serpiente (1987); Casa Cacahuate (1989); The Mexican Whale (1992); Flower House (1994); Ciudad Satélite (1995); Nautilus House (2007); the serpent-shaped 10-unit apartment complex (available for rent on Airbnb) Quetzalcóatl’s Nest (2007); and, in São Paulo, Brazil, the gold- and copper-patinated Amoeba House (2012). In 2016, the National Museum of Architecture INBA in Mexico City mounted a retrospective of the architect’s built and unbuilt designs including a utopian (still) yet-to-be-realized eco-village for affordable housing in Mexico City. He is also the author of two pivotal books on bio-architecture, Organic Architecture of Senosiain (2008) and Bio-Architecture (2003).

Senosiain’s prime influences are frequently cited as the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, and Mexican architect/engineer Félix Candela. Other influences are the Mexican architect/painter Juan O’Gorman, who designed the Diego Rivera/Frida Kahlo houses/studios, and Austrian architect/painter Friedensreich Hundertwasser. But whereas Frank Lloyd Wright’s concept of organic principals generated geometric straight-line abstractions, Senosiain’s work bears free-form organic abstractions. His curvilinear plastic forms have no straight lines and, as with Gaudí, are based on forms from nature. His designs incorporate 21st-century sustainable concepts such as passive systems (non- mechanical) for heating and cooling, and rainwater collection for irrigating the lush plantings that envelop his architecture. A simple system he uses for natural cooling and heating is to orient the windows of a house south. The windows are then protected with eyebrows that shade the interior from the hot summer sun. In winter, these eyebrows allow low-angle direct sun into the interior to facilitate heating. Unique to most of the architect’s designs is the incorporation of earth sheltering, which not only insulates his domestic structures with earth mass but also enfolds the built forms with and into the natural landscape.

The house Javier Senosiain designed and built for himself and his wife in 1984 is located in Naucalpan de Juárez, on the outskirts of Mexico City. Casa Orgánica was originally called Casa de Piedra (House of Stone) because the site he purchased was filled with natural stones. His first organic thoughts were to build walls with the stones from the site. As the design progressed, the architect became concerned that there was no continuity between the floor, wall, and ceiling because they were made of disparate materials. This led to an exploration for materials integral to the curved form.

Similar to the works of Félix Candela, Casa Orgánica’s curvilinear plastic forms bio-mimic an eggshell, which by its shape is thin but very strong. The underlying support structure was achieved by using innovative construction materials and methodology: The structural cage of steel reinforcing bars was covered with a wire mesh on both sides and sprayed with ferrocement to forge its rigid shell. This understructure was then sprayed with a 3⁄4-inch-thick layer of polyurethane foam before being covered with a water-proofing mastic. For the final process, earth from the excavation of the site encased the completed shell to act as a biomass stabilizing interior temperatures in a range of 18 to 22 degrees C (64 to 72 degrees F) with 40 to 60 percent humidity.

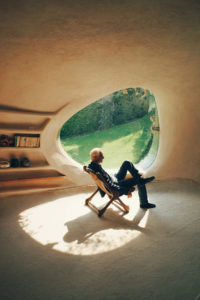

Javier Senosiain describes the design evolution of the house that served as the DNA of his practice: “The original idea of the project took its smile from a peanut shell: two wide oval spaces with lots of light, united by a space in low and narrow gloom. The two large spaces, one day and one night, [suggest] the feeling that the person will enter … aware of the uniqueness of this space without losing integration with the exterior green area.” To this end, the public oval day space contains the living, dining, and kitchen areas and is filled with abundant natural light. The private oval night space contains the sleeping, dressing, and bath areas, distinguished by moderated natural light. Connecting the disparate areas, akin to hallways, are compressed darkened curved tunnels, always leading to larger open and lighted areas.

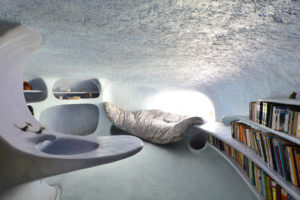

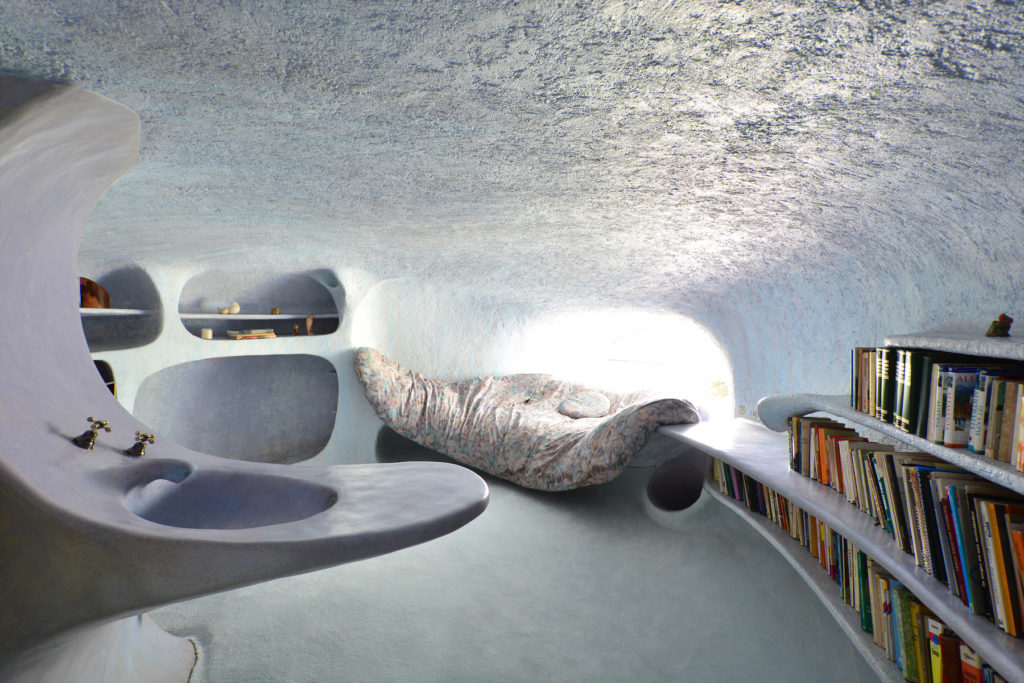

From the exterior car park, one approaches the house using a spiral stair leading up to the entry — a shape reminiscent of a shark’s mouth, emblematic of the architect’s playful introduction of animal and/or mythic associations into his dwellings. The entry segues into the beginning of a curved darkened tunnel, which dramatically connects to the public area. This ample, continuous public space is punctuated by biomorphic curving glass windows and a door that connects the interiors to the verdant tropical garden that envelopes Casa Orgánica. Joining public and private area is another long, curvaceous, darkened tunnel. At its terminus are the private areas — bedroom/study, dressing, bath. The bedroom makes use of built-in furnishings to expand the space — a banquette-lounge seat and bookshelves, both organically tucked into the curve of the walls. The dressing area continued this use of built-ins, tucking closets into the free- flowing walls. The bath encompasses a built-in tub, illuminated by a clear overhead skylight perfectly sited for moon gazing.

As the family grew another private oval space was added for their two girls, containing a shared bedroom, dressing area, and bath. The new wing was attached to the tunnel midway between the original public and private areas. The girls’ bedroom continues the house’s curvilinear motif, with nook beds surrounded by walls. Vistas upon the garden are provided by an expansive curved glass window and glass door. The dressing area employs built-in closets, while the bath features an organic built-in tub. But the most important aspect of the addition of the girls’ bedroom was the articulation of the house’s unique shape, which evolved to become a sea creature, adding a dose of whimsy without sacrificing the home’s pervading organic fluidity and environmental principles. Javier Senosiain says, “The masons started calling the shape the shark, so I put a fin on it, and then it was like a shark.”

As in the works of Frank Lloyd Wright, almost all the furnishings in Casa Orgánica are built-in. These forms intuitively follow the curvilinear walls and are constructed of either natural wood or ferrocement finished with a paste of marble powder in white cement. Also built into the curving walls are nooks with clear glass shelving utilized to display objects of art. The floors are covered with a wall-to-wall continuous deep-pile carpet in a light sand color. In turn, walls and ceilings are painted to match the carpet, visually creating a single unified volume while fostering a lively dialogue of interior with exterior.

At completion, the earth surface atop the house was landscaped with grass and plants to integrate its biomorphic forms seamlessly into the natural landscape. The total enclosed area of Casa Orgánica, a modest 1,873 square feet, offers enough space for a family of four, as well as endless vistas of green that make the house truly a part of its luxuriant surrounding terrain.

The architect and his wife no longer live at Casa Orgánica; they moved 12 years ago to a house he designed in Mexico City that pairs elements of organic architecture with an ode to Luis Barragán. At the moment, Casa Orgánica in uninhabited. Nonetheless, the house is rigorously maintained by Senosiain’s firm and his gardening and maintenance teams. Current plans call for the residence to be preserved as a house museum, owned and operated by the family, with public tours, bookable through Casa Orgánica’s website, offered four days a week.

As for Senosiain, his individualistic practice parallels that of Gaudí for more than its curvaceous displays of whimsical creatures adorned with tiles. Like Gaudí, this contemporary Mexican architect also embraces parks and epic, long-term projects. Since 2000, he’s been creating Parque Quetzalcóatl outside the Mexico City metropolitan area, a summation of his life’s work to integrate humans into nature (en.parquequetzalcoatl.com).

Postscript: Although I’ve been in the field of architecture and the built environment for nearly a half-century and a disciple of organic architecture and its practitioners, including my mentor, architect Bruce Goff, I had never, until now, heard of Casa Orgánica nor its brilliant, but under-known creator, Javier Senosiain. “Organic architecture is the philosophy of architecture that seeks harmony between human beings and nature,” Senosiain aptly says of his dwelling. “One of the characteristics of this house and perhaps the main objective is that the structure adapts to one’s body.” This is analogous to dance and reminds me of a quote from Martha Graham: “A philosopher said that dance and architecture were the first arts.” Indeed, this rare feeling of the primal is pervasive in Senosiain’s defining early work, which became the timeless calling card of his practice. As the house’s website states: “Casa Orgánica was intended to give the sensation of entering the earth.”

Thirty years after completion of this singular house, Senosiain tells PaperCity, “For me, since the beginning, the intention of the house was very clear; to look back into the origin, the primitive. What I found peculiar is how people nowadays are more amazed about the house than back when it was built.”

Architect Robert Morris is a retired professor from the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design at the University of Houston, where he taught environmental design in architecture and space architecture.

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)