Palace Intrigue — A Fort Worth Estate With A Design Pedigree and Scandalous Past is Refreshed By Dunbar Road

Architectural Elements and Antiques Purchased From Palatial American and European Residences

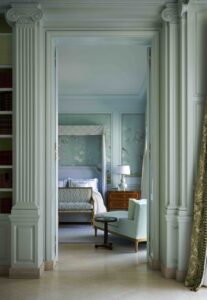

BY Rebecca Sherman // 10.21.24Inside the Young Estate in Fort Worth, the library’s centuries-old Georgian molding and pilasters were brought from England in the 1970s. Dunbar Road’s refresh includes a custom gold-leaf chandelier and Gainsborough silk wallpaper. The Italian side tables are 1940s. Custom sofa and chairs are upholstered in Pierre Frey, Pindler, and Designers Guild fabrics. (Photo by Pär Bengtsson)

At first glance, the neoclassical house on Spanish Trail is just another sprawling mansion along this leafy boulevard in Westover Hills, an exclusive, old-money enclave nestled on the western edge of Fort Worth. Known as the Young Estate, the 17,000-square-foot residence is anything but typical. Behind the stately white columns and cut-limestone façade lies a house of remarkable design importance — with a notorious backstory.

Conceived in 1975 by Hollywood architect and interior designer Michael Morrison for two of Fort Worth’s most colorful members of high society — late oil wildcatter William Kelly Young and his wife, Connie Bolin Young — the interiors were filled with priceless architectural elements and rare antiques, much of it acquired from palatial residences around Europe such as Mentmore Towers, a 19th-century English country house built for the Rothschild family. But the real treasures were salvaged from Rose Terrace, a Versailles-like estate in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, completed in 1934 for Anna Dodge, widow of automobile pioneer Horace E. Dodge. One of the richest women in the world, Dodge spent her vast wealth turning Rose Terrace into a palace worthy of kings.

Dunbar Road Refreshes Fort Worth’s Young Estate

Fast forward to present day. Carla Fonts, founder of the Dallas design firm Dunbar Road, has just finished phase one of an extensive two-part refresh of Fort Worth’s Young Estate, which hadn’t been touched since the 1970s. “So far, we’ve done the kitchen, the library, five upstairs bedrooms, and 11 bathrooms that I can remember — I lost count,” Fonts says. Her clients are a couple who purchased the house 20 years ago and raised their children there; the wife is originally from Michigan and knew the house’s historic significance. Fonts recalls, “One of the things they kept reiterating to us was: ‘Please be good stewards of the house, honor the structure of the home.’”

The Young Estate reminds Fonts of the grand antiques-filled houses by society architect Addison Mizner in Palm Beach, where her parents and grandparents lived after fleeing Cuba. The vibrancy of Palm Beach influences Fonts’ own design work, with an emphasis on bright colors and a mix of European antiques.

Her initial focus has been on the private areas. “Those rooms deserved to be as palatial as the rest of the house,” she says. The bathrooms all have exquisite Sherle Wagner fittings, and elegant materials were used in the bedrooms including Scalamandré and Pindler silks, Lee Jofa velvet, and Samuel & Sons trims. “I wanted each bedroom to have a uniqueness,” Fonts says. They range from a smoky elegant men’s-club feel with plaid Stark carpeting and deep-blue velvet Holland & Sherry draperies to an English-cottage-garden look with embroidered Pierre Frey headboards and chinoiserie wallpaper.

The library’s frothy blue and green pastels, custom gold-leaf pagoda chandelier, and lime-green Gainsborough silk wall panels are a light-hearted interpretation of 19th-century aristocracy. “I’m a big Bridgerton fan,” Fonts says, referencing the popular Netflix period drama, “so I wanted to bring in those lively, fresh colors to give the room a little uplift.”

Areas with historic significance were lightly touched, such as the downstairs powder bathroom, a rotunda-like space with columns, antique Chinese wallpaper and polished travertine floors with a radiating sun mosaic designed by architect Michael Morrison. A future refresh of the Music and Oak Rooms will include new upholstery and furnishings, says Fonts, but will leave the 18th-century paneling and other original elements undisturbed.

Brent Hull, founder of Fort Worth-based Hull Millwork and an expert in historic restoration, revived the mansion’s antique interior and exterior doors, windows, and molding; in areas where they were damaged or missing, he copied and rebuilt them. The Young Estate, like Rose Terrace, was built to last, with steel, concrete, and thick slabs of cut limestone. “The high quality of craftsmanship, scale of the rooms, the history and tradition are what make this house so special,” Hull says. “They just didn’t build houses like this in the 1970s. You walk in and think, ‘There nothing else like it in America.’”

The Inspiration Behind the Young Estate — Rose Terrace

To understand the social and historical significance of Fort Worth’s Young Estate, it’s important to revisit Rose Terrace in Grosse Pointe. At the time of Anna Dodge’s death in 1970, the Detroit automobile heiress had amassed a fortune that today would be worth just shy of $1 billion. According to her New York Times obituary, Dodge presided over multiple residences, including a 100-room mansion in Palm Beach and homes in London and Southampton. Her magnificent jewelry collection was highlighted by a $1 million pearl necklace made for Catherine II of Russia — which Dodge wore only twice.

But the real jewel in the grand dame’s glittering crown was Rose Terrace, a sprawling French neoclassical-style château built during the Great Depression. The 75-room mansion was designed by Horace Trumbauer, a Gilded Age architect for America’s upper crust, known for Miramar in Rhode Island and Ardrossan, the Main Line manor that inspired the 1939 play The Philadelphia Story.

Rose Terrace was considered Trumbauer’s best house and the finest of its type in America. Exquisite detailing included carved 18th-century boisserie rooms illuminated by enormous antique bronze and rock crystal chandeliers. Advised by noted art dealer Lord Joseph Duveen, Dodge and her second husband, Hugh Dillman, traveled to France, Russia, England, and the Orient, collecting treasures for the house. They filled the 42,000-square-foot estate with French decorative arts and masterpieces by Gainsborough, van Dyke, and Boucher, along with furnishings from the imperial palaces of Russia and Versailles.

Of all the interior spaces, Dodge’s favorite was the 18th-century Music Room, a ravishing entertaining space she transformed into a ballroom for her granddaughters’ society debuts. It was filled with centuries of regal furnishings, including sconces that once belonged to Marie Antoinette and a collection of royal Sèvres porcelain including a bureau plat bought by the future tsarina of Russia when she visited Paris in 1782. These inestimable riches were set against a dazzling backdrop of Louis XVI paneling with 24K gold embellishments. After her death, the Music Room’s collections and furniture were willed to the Detroit Institute of Arts, with the house’s remaining contents auctioned by Christie’s in 1971 — a dozen or so pieces can be seen today in the Getty museum collection.

Anna Dodge’s heirs tried but failed to find a buyer for Rose Terrace itself. Despite the mansion’s status as a Michigan State Historic Site and listing on the National Register of Historic Places, the house was demolished in 1976. Writing for Town & Country in 2017, interior designer David Netto lamented Rose Terrace as a missed opportunity: “Think of it as the Penn Station of American houses, the great museum that never was, a Frick Collection for Detroit. The demolition of Rose Terrace in 1976 was a great loss in the American cultural landscape.”

While the house’s bulldozing was a travesty, one thing was done right: Its superb antique architectural elements were carefully salvaged and put up for sale.

Building Fort Worth’s Young Estate

When Fort Worth oilman Kelly Young saw the classical house that Michael Morrison designed for renowned philanthropists Ben and Kay Fortson, he wanted one like it. Morrison obliged with Corinthian columns and a soaring, curved glass entryway — his spin on Andrea Palladio’s seminal Villa la Rotonda. Classical architecture suited Morrison’s understated, quiet demeanor, but he also knew how to make a glamorous statement. Before starting his own firm, Morrison worked for legendary Hollywood decorator William Haines, whose clientele included Joan Crawford, Frank Sinatra, and Betsy Bloomingdale.

Like the lengthy buying sprees of Sir Joseph Duveen and his client Anna Dodge, Morrison took Kelly and Connie Young on extensive treasure-hunting expeditions across Europe. There, they acquired 17th- and 18th-century furniture — much of it signed — along with antique marble fireplaces and fountains, Chinese wallpaper, and Aubusson rugs. At a Sotheby’s auction of the contents of Mentmore, Baron Mayer de Rothschild’s English country estate, they purchased several large urns, an 18th-century ormolu commode, and Italian dining-room chairs so big and ornate that Morrison later deemed them unusable. On a shopping trip to Italy, they bought a Roman fountain for the entryway. The house’s pinky terra-cotta exterior took inspiration from an Italian villa Connie had admired; she snapped a picture of it and showed it to her good friend, the late heiress Anne Burnett Tandy, who raved about the choice of color and helped her refine it.

In 1976, Morrison arranged for a tour of Rose Terrace ahead of a pre-demolition architectural sale to be held by Detroit property auction firm Stalker and Boos. The vast estate had been empty since 1971. When the sale ended, the Youngs were the owners of a large trove of Rose Terrace embellishments. Their contractor, Bill Taylor, who had worked on some of Westover Hills’ best houses — including Sid and Anne Bass’ Paul Rudolph-designed masterpiece — was on hand to pack it all up. In the end, six trucks headed to Texas loaded down with antique stone pilasters and balusters; miles of French 18th-century molding and paneling from the Oak Room and Anna Dodge’s beloved Music Room; a half-dozen rock-crystal chandeliers; 20 pairs of antique French doors; hardware handmade in the 1930s by P.E. Guerin; and a marble tub and sink from Dodge’s private bathroom.

The Youngs hosted elegant parties in their new pink palace, attended by Fort Worth society. “Connie and Kelly were quite popular,” one longtime friend told me. “She was pretty and glamorous, and he was rich and powerful.” A Fort Worth Star Telegram society columnist who covered a reception in the early ‘80s noted its “interesting combination of antiques and contemporary art,” with a series of Matisse cutouts in the entry complementing the Roman marble fountain, in which pink blossoms floated.

Connie, a former flight attendant from Arkansas, had come a long way from her small-town roots. There were several portraits of her by Andy Warhol and a large work by Frank Stella in the library; a Helen Frankenthaler hung in the Music Room. New York artist Aaron Shikler — who famously captured the likenesses of President John F. Kennedy and first lady Jacqueline Kennedy — painted a two-sided portrait of Connie, which she prominently displayed in the Oak Room. On one side, it featured the flame-haired beauty in a green Lanvin evening gown, one bare foot peeking daringly from the hemline and her face in profile — a pose Shikler had suggested. On the other side, he painted her facing forward, an angle Connie preferred.

“She was a strong personality who was very determined; by that, I mean she knew what she wanted — and she got a lot,” a friend says. “They had an airplane and would fly off to Aspen. Kelly was so rich, he gave her everything.” When Connie wanted a bigger diamond ring, they flew to New York to choose a stone, returning with a dazzling 10-carat pear-shaped diamond, which Haltom’s Jewelers set. Connie’s closet was full of couture gowns from Neiman Marcus in Dallas, including some by young American designer Alfred Fiandaca. After she expressed dissatisfaction with that season’s fabrics and colors, Fiandaca dashed off to Europe to select new materials in sunset colors to flatter Connie’s complexion. The Youngs’ 1983 Route 66-themed bash at the Ridglea Country Club for Kelly’s daughters, Alison and Shannon, was “sure to be the party all debutante parties in Fort Worth are measured against for the next 20 years,” a local society columnist gushed.

The fairy tale soon faded, however, and the couple divorced in 1986. According to court documents, Connie was given custody of the couple’s two sons and the right to live in the Fort Worth mansion for three years, after which it would be sold. Kelly agreed to pay her $10,000 a month during that time — money she would repay with proceeds from the sale of the house. In accordance with the agreement, the house was put on the market in 1989, and their roughly $2 million in furnishings were inventoried, which they would eventually split. The house failed to attract a buyer; in 1991, a receiver was appointed by the court to sell it.

But Connie had a very different plan in mind.

The Young Estate Scandal

The Young’s divorce and bitter fight over the mansion and its precious contents set into motion a series of outrageous events, complete with a cast of outlandish characters: a corrupt Arkansas lawyer straight out of Better Call Saul, an FBI wiretap, and millions of dollars in purloined antique furniture, chandeliers, and architectural elements. But it was Connie’s conspiracy to blow up the couple’s Fort Worth mansion with explosives that landed her in federal prison for two years.

The strange and marvelous tale of one of Texas’ most significant houses and the scandal that rocked Fort Worth society has been long forgotten — until now. The events that follow are retold from public records, court filings, newspaper archives, and my interviews with Connie, who is now 81 years old; it’s the first time she’s spoken publicly about her role in the scandal that took place more than 30 years ago.

Divorce, Texas Style

Connie Young was furious. Her efforts to block the sale of Fort Worth’s Young Estate had failed, according to federal prosecutors, who said she had turned down offers from interested buyers, including one for $2.5 million. With a court-ordered sale of the house looming, Connie retaliated against her ex-husband, Kelly Young, by refusing to let him see their two sons, court records allege. Kelly filed suit against her, claiming she attempted to tie up the terms of their divorce in legal battles with untrue claims. He testified that Connie also tried to get him thrown in jail for threatening to kill her, charges that were later dropped. Texas state district judge Catherine Adamski Gant awarded Kelly $3.2 million for breach of contract, emotional distress, and damages — twice the amount he had sought. Kelly was also given his ex-wife’s house in Springdale, Arkansas, her hometown.

Connie’s lavish lifestyle was careening to an abrupt end. Heavily in debt to Kelly, she was about to lose everything, including her cherished Westover Hills house and the priceless heirlooms inside. Then David S. Post entered the picture. An attorney in Fayetteville, Arkansas, Post was already under FBI scrutiny for his part in a massive insurance fraud scheme that included spurious slip-and-fall accidents, car wrecks, and other scams.

The FBI was listening in when Connie and Post discussed plans to strip the house of its treasures, then blow it up with explosives to collect the $7 million insurance policy. In November 1991, Connie paid her friend Alex Montez $15,000 to do the deed. Connie again met with Post and Montez in March 1992 to discuss the scheme’s potential risks and how to distribute the money. During the meeting, Connie devised a foolproof alibi for the night the house was to be destroyed: She would arrange to have dinner with Benton County Circuit Court Judge Tom Keith, an acquaintance who knew nothing of the plot. The FBI got it all on tape.

Meanwhile, Connie had millions of dollars’ worth of antique furniture, lighting, and fixtures removed from the Westover Hills house and hidden. Five storage units around Springdale were later discovered full of the stolen goods, but much of the house’s contents was still missing, including the antique rock crystal chandeliers and marble mantels.

In August 1992, Connie and her co-conspirators were charged with mail fraud in connection with the plot to blow up the mansion. While Connie awaited trial in Arkansas, Kelly continued to search for the missing antiques. Despite a court order requiring her to answer questions about the looted goods, she refused — twice. The Judge found her in contempt and had her thrown in county jail.

Connie Young’s fraud and conspiracy trial opened on February 18, 1993, in Arkansas federal court. Over two days, jurors heard testimony from her friend Alex Montez, who claimed Connie had backed out of the bomb plot and he simply “conned her out of the $15,000.” Montez, who was under subpoena, also alleged Connie had asked him days earlier to alter a date in order to better suit her defense. She was convicted and later sentenced to 24 months in federal prison.

The Fallout of Fort Worth’s Young Estate Scandal

The news was met by old Fort Worth society with a mix of shock and amusement. “It was just a crazy, totally bizarre story,” says a friend, “but it wasn’t totally out of character. It’s not like she was a sweet little thing — she was strong headed.” The Northwest Arkansas Times covered her indictment and trial extensively, but the scandal was hush-hush in Fort Worth; despite the fact that Connie Young was one of its most prominent citizens, I could find no record of her sensational arrest and trial in the Fort Worth Star Telegram archives. The Youngs were — and remain — a well-liked and powerful family in Fort Worth, and Kelly, for one, quickly buried the hatchet. After Connie’s release in January 1995, he set her up in an apartment in New York City and bought her houses in Aspen and Dallas. “He continued to take care of her; despite everything that happened, he still really loved her,” the friend says.

Beauty for Ashes

These days, Connie travels and spends time in creative pursuits, like painting, which she picked up after taking classes in the ‘70s with artist Aaron Shikler at his New York studio. She splits her time between homes in New York, Dallas, and Arkansas. “I have an excellent life now — I try and stay positive,” she tells me. Understandably, she doesn’t like talking about the scandal that led to her legal troubles so many years ago. “Let’s put it this way: I was getting a divorce,” she says. “We had differences of opinion on our settlement. The judge gave everything to Kelly, and I just absolutely had a fit. And that’s all I’m saying on a personal level.”

Instead, she talks about her brief, still-fond memories of the Westover Hills house. “It was quite magical. I especially liked it during the winter months, when all the fireplaces were going,” Connie says. She’d recently seen pictures of the house and Brent Hull’s video documenting the restoration on YouTube. The gilt panel over the Music Room’s fireplace was added by a subsequent homeowner, she points out. “I removed the original panel in a fit of anger. I removed quite a few things from the house — all the rock-crystal chandeliers.” Despite the changes, she thinks her former Fort Worth estate has held up well.

“It was exquisite when Michael Morison first completed it — he and Bill Taylor were at the top of their game,” she says. “The house definitely had all of my touches; it was enjoyable, creating something of such great beauty.”

_md.jpeg)