Houston’s Own Light House: This Stunning Museum District Home Brings the Outdoors In With Fantastical Flair

BY Rebecca Sherman // 07.11.16Walnut table by German manufacturer Wilkhahn, with vintage Zanotta leather chairs from Kuhl-Linscomb. Mies van der Rohe stools in the kitchen were originally designed for the Four Seasons restaurant in NYC. The commissioned round painting is Darren Waterston’s "Tondo," 2013, from Inman Gallery. Bronze figure is by Mario Korbel, 1923. A partial wall made from Parisian limestone hides a staircase in the entry.

THE BOUNDARIES BETWEEN INSIDE AND OUT BLUR IN WAYNE BRAUN’S ART-FILLED MUSEUM DISTRICT HOUSE.

After 15 years of cramped high-rise living, Wayne Braun was ready to expand.

“Frankly, I got tired of being stuck in a building. I decided it was time to get back down to earth,” says Braun, design director emeritus of PDR, a Houston design and interior architecture firm. “After so many years in a condo, the connection to the outside is what I missed the most — the ability to walk outside easily, back and forth.”

When the kids were out of college, and a large lot in the Museum District came on the market in 2011, the timing was right to build a house from scratch, says Braun, who designed the architecture and interiors for his new house, completed in 2013. Brendan Custom Homes acted as general contractor. For inspiration, he looked to works by international style greats Le Corbusier, Gwathmey Siegel and Richard Meier, who are known for their elegantly simple, rectilinear buildings with open interior spaces enveloped by glass.

“What resonates most with people about my house is how light and bright it is, even on rainy days,” he says.

On the first level, 24 by 9 feet of sliding glass doors in the living room and 16 by 9 feet of windows in the dining room surround a private courtyard with lap pool.

“When you open the glass doors in the living room, it completely changes that room into a giant cabana,” he says. “It’s like you’re really outside. That one aspect is truly transformative.”

“I’m a frustrated architect, so I always wanted to design my own home,” says Braun, who began college majoring in architecture in the mid-1970s at the University of Kentucky but later changed to interior design.

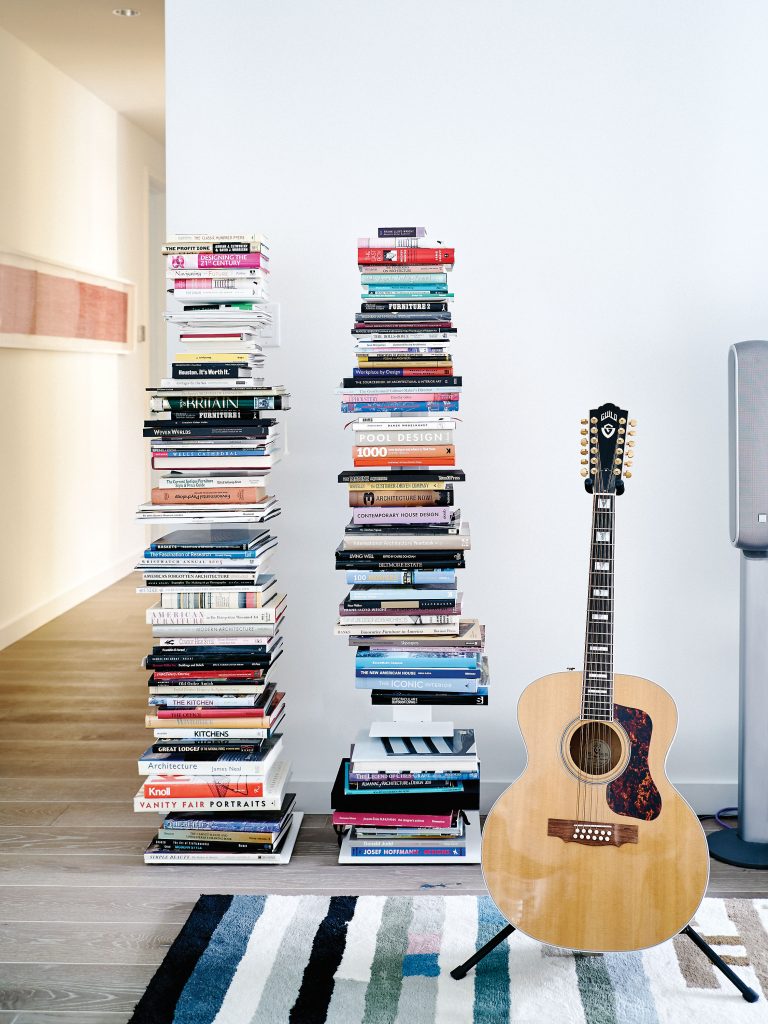

His passion for construction and form found another outlet: designing office furniture for a half-dozen manufacturers including Steelcase and HBF (Hickory Business Furniture) in his spare time.

“I always saw furniture as miniature architecture since it’s three dimensional,” he says. “I also have a fascination with woodworking because of its manipulability and natural surface patterns. There’s a foreverness about beautifully crafted wood furniture.”

Some of his own furniture designs fill his new home, including a sleek marble console and a contemporary version of a Victorian rolltop desk crafted in maple with exquisite nickel teardrop pulls.

“When I design furniture,” he says, “I always design custom hardware. My attitude is: If that’s where the human hand touches, you need something unique and tactile.”

Other furnishings in the house were chosen for their sculptural qualities, such as simple Shaker-style side tables, an Arne Jacobsen floor lamp designed for the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, a vintage bentwood mahogany Ward Bennett chair, and a pair of chrome-and-red-leather Mies van der Rohe bar stools that were originally designed for The Four Seasons restaurant in New York. A pair of 1950s Hans Wegner chairs was purchased with an inheritance left to him by his godparents, whose home was furnished in mid-century style.

“I think about them every time I look at the chairs,” he says.

Braun’s collection of mid-century furniture is interspersed with a sleek new B&B Italia sectional and Minotti ottomans purchased specifically for the house’s large-scale, open rooms. Those ottomans help transition the indoor space to the inside.

“They look like they could be made for the outdoors, but they’re not,” he says. “I wanted something low that you could see over. I’ve had events at the house with over a hundred people, including the Rice Design Alliance. With the door slid open, it’s a great way to tie the two spaces together.”

For the dining room, he purchased a massive seven-foot walnut table by Wilkhahn, the esteemed German manufacturer of conference furniture.

“It was important to me to get a round table for this house,” he says. “There’s something special about being with friends and being able to see everyone.” Because Braun is an interior designer who also thinks like an architect, he gave plenty of consideration to how the architecture would aesthetically support his growing art collection.

“I wanted to have a space that celebrated the art and was not just a passive foil for it,” he says. He worked closely with Julie Kinzelman of Kinzelman Art Consulting to buy artworks for specific areas in the house. “She understands what art can do for you in a bigger sense, in terms of your emotions and how you enjoy it,” he says. “The works I gravitate to show how the artist created the piece.”

One example is a complex paper wall sculpture by Japanese artist Jacob Hashimoto, which hangs in the living room.

“It’s a fabulous piece of execution, and everybody loves to look at the various layers,” he says. “It has a magnetic draw.”

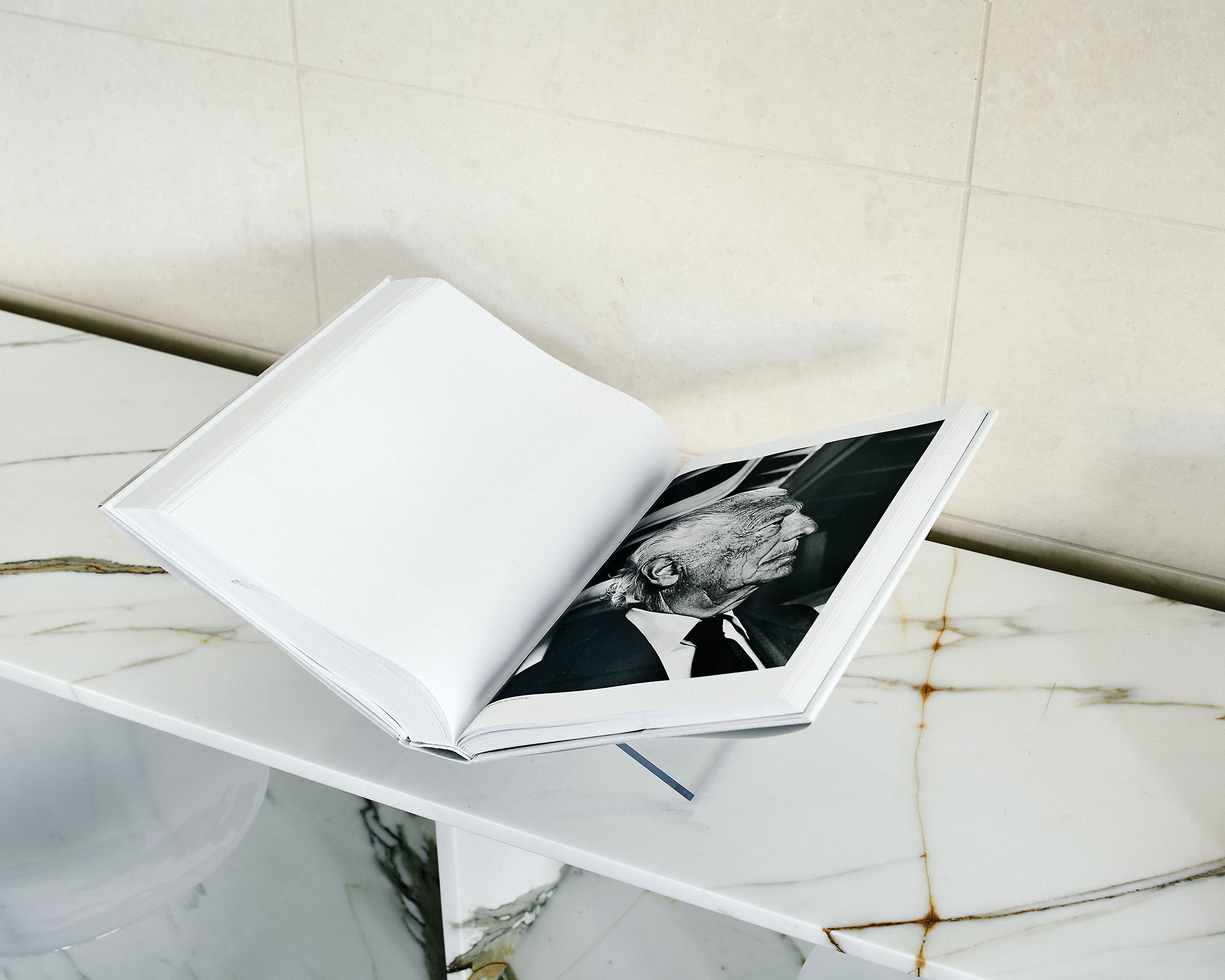

A black-and-red 1967 lithograph on cheesecloth by Louise Nevelson that hangs in the master bath is highly textural and shows the artist’s hand at work. And artist Makoto Sasaki, using a quill pen and red ink, recorded a dozen hours of his own heartbeats onto paper to create 12-Hour Heartbeat , which hangs in Braun’s guest bedroom.

“It looks like a textile, then you realize it’s ink. It’s continuous. He never lifted the pen.” Braun also has collections of hand-turned wood vessels (including one by Philip Moulthrop, one of three generations of the legendary Moulthrop family of woodturners in Georgia) and woven baskets.

One basket is by Billie Ruth Sudduth, an acclaimed basketmaker living in the mountains of North Carolina whose works are in the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery.

“She was a former math teacher who was interested in the geometry of basket weaving,” Braun says. “I visited her at her studio and bought it. It’s one of my favorite pieces.” Other art obsessions include figurative cast bronzes from the late 19th century through the 1920s and 1950s. “The castings are so beautifully done; the sculptural technique and the images are less intellectual than most art, so it’s more about the craft.”

For that reason, he was also attracted to contemporary artist Christopher Smith’s 14 aluminum-infused cast resin nude sculptures, which are mounted in the stairwell, and English artist Nick Hornby’s 2011 angular, stylized bronze profile of Jane Austen.

Braun’s art and furnishings are all highly personal collections — even the architecture he created for the house speaks volumes about the man.

“Spaces should be uplifting,” he says. “I spend most of my time on the first floor, on the sofa, looking outside, reading or sketching. I come down in the mornings, slide open the doors, shut off the air conditioning and have coffee. It’s so fine to look out at plants and trees, to be a part of nature.”

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)