Art World Darlings The Haas Brothers Take Texas With a Career-Defining Exhibition at The Nasher

Inside Their New, Otherworldly "Moonlight"

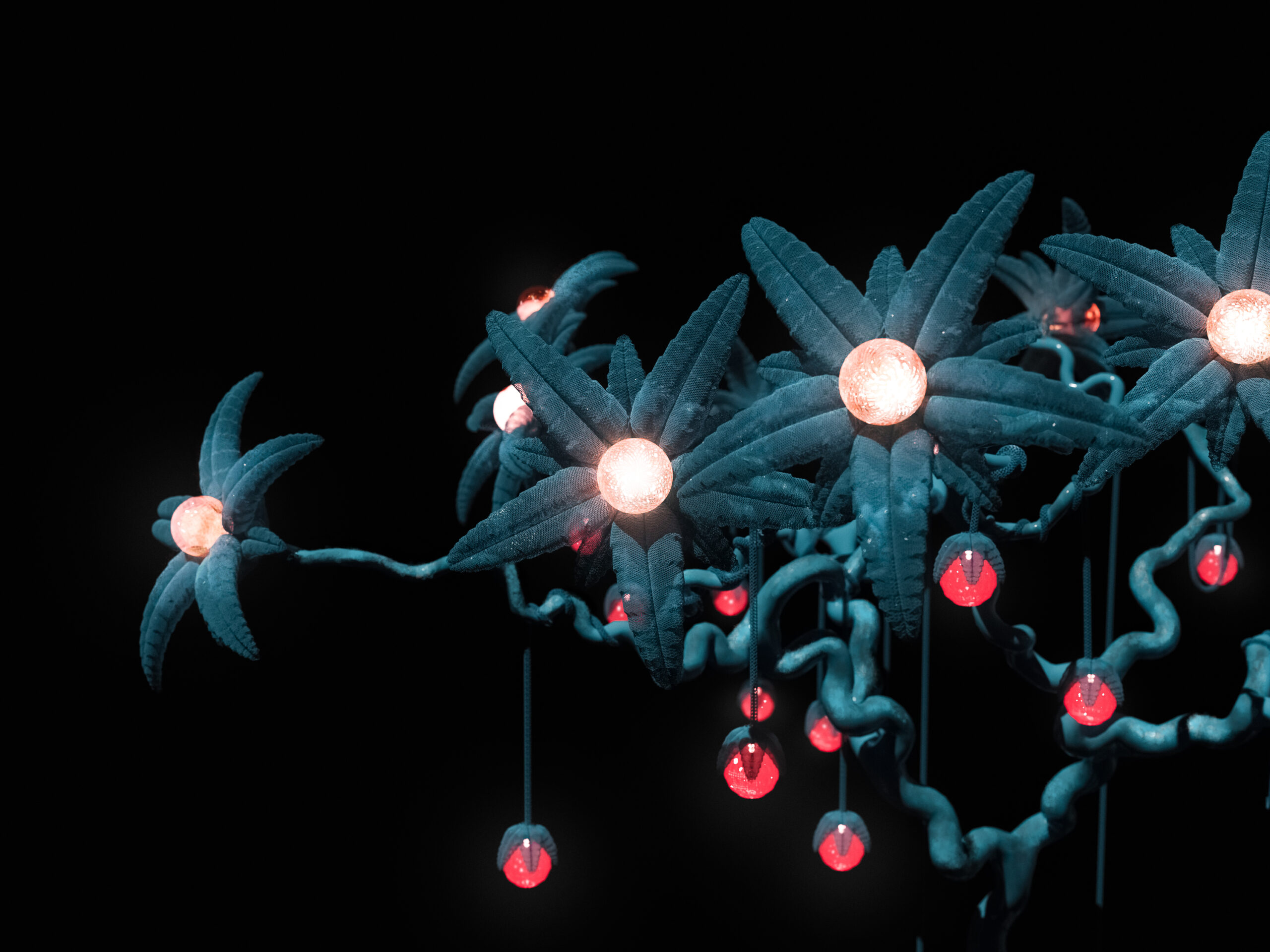

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 05.10.24Digital rendering of The Haas Brothers’ "The Strawberry Tree," 2023.

On the eve of a career-defining exhibition, Nikolai and Simon Haas sat down in their North Hollywood studio for a Q&A about their upcoming solo, “Moonlight,” at Nasher Sculpture Center. Via Zoom, the brothers — darlings of both the art and design worlds who are represented by powerhouse galleries Marianne Boesky, Jeffrey Deitch, and Lora Reynolds — open up about their Texas homecoming, the surprising role the Nasher played in their early lives, why creativity is in their DNA, and who played key roles in making their Nasher debut happen.

In Conversation With The Haas Brothers

Catherine D. Anspon: Take us back to the beginning. How did your Nasher show come about?

Simon Haas: It started through our Austin gallery owner, Lora Reynolds, who was showing our work at the Dallas Art Fair in 2018.

Niki Haas: She knew Jeremy Strick [Nasher Sculpture Center director], and then we all met; it was sort of easy. Lora set up that conversation and knew that we would like each other. Then we did a talk with Jeremy at the Nasher, as part of Dallas Art Fair in 2018. We had such good rapport, and I think we were surprised by how much we liked each other. We started putting down some designs, and then met Brooke [Hodge, independent curator], about three years ago, partway in, and she started organizing the show and tightening it up. We’ve been working on the “Moonlight” show for five years.

CA: I see you opened a major exhibit with Jeffrey Deitch in L.A. last fall and will present a solo at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York City concurrent with “Moonlight.” Are you also still with Austin gallerist Lora Reynolds too?

NH: Totally. Lora is special. We love Marianne. We love Jeffrey too. They’re real mentors. But Lora holds some kind of special something. I can’t quite articulate it. Like being a sister. If I was in trouble, I’d call Lora.

CA: The Haas Brothers have had museum shows, but the Nasher is an international destination for sculpture. Is the bar higher?

SH: This is our biggest show ever. We grew up going to the Nasher because we grew up in Austin. This was a huge deal for us to have a show here. It’s just a gorgeous museum. And the scale of what the Nasher has let us do is bigger than we’ve ever done. We have things out front, works in the back sculpture garden, and something inside, which is really cool.

NH: This is our biggest show for sure. And it’s landing on the 15-year anniversary of the opening of our studio. So, it feels important in a lot of ways. The Nasher opened in our later high school years, in 2003. I remember that they commissioned Renzo Piano for the architecture and the level of culture that it brought to Texas. I remember going on a high school field trip to see it and being completely dumbfounded with how good the work was. And, also how holistic it was, because the Nasher was based on a collection of an amazing amount of work that two people had been amassing for a long time.

It’s cool to have seen it grow so much, and that we were at the front edge of our adult lives, leaning into this next venture of what we were going to do, and art and sculpture were vaguely available to us in terms of a potential career. It really does feel full circle. It’s the biggest moment we’ve had in our career and it’s a homecoming at the same time. The Nasher is a personal thing for us.

CA: Is there a certain sculpture that comes to mind when you think about the Nasher? A touchstone, perhaps?

SH: I recently experienced my favorite Nasher show, Harry Bertoia. The Bertoia show was up when we were working on this show. I was stunned by it. It’s very process-driven in a way that I relate to, and just weird and experiential.

NH: The touchstone I think of is the Richard Serra in the back garden, which had a major effect on me. I hope that we have that sort of ubiquitous presence at some point in the future — that we could in a sense be followed by a young artist.

CA: On the making of “Moonlight.”

NH: The show is brand-new. None of it had been proven before we made it — it was really exhilarating for us to be working at such a scale, with a purpose, because sometimes we’ll just make something huge to express ideas, and that’s a different sort of fun, interesting way to make work. But to have an intrinsic higher purpose instilled in the making of a work makes it feel more important and motivates us as makers to do the absolute best that we can do because installing something at the Nasher, in my mind, feels almost holy. It would hold that place in my spirit. And it reflects the level of attention and the brainpower that we put towards this show.

CA: On the challenges of bringing forth this epic exhibition.

SH: We made all our own challenges, because the Nasher has been so professional — one of the easiest institutions we’ve worked with, and so trusting in our vision. We wanted to build something really difficult to build … and it’s proven to be super difficult. But we were able to do it, which is cool. For this show, we wanted to be on that edge: If you’re doing something slightly outside of your ability, then you’re probably making some of your better things. That was the point for us.

CA: On the heroically scaled high points.

SH: There’s The Strawberry Tree, in the middle of the gallery. We would never have been able to make this until now. We’ve been striving for it for a long time. It’s made of beads and bronze and glass and stone, and it’s on an intricate level of detail on a large scale. It’s sort of a dream object. And the Nasher gave us the opportunity to make it.

NH: It’s 15 by 18 by 21 feet. We built huge parts of it with antique Murano beads, 1/16 of an inch each. It’s this massive scale with super, super high detail. I think it took 50 of us to build the thing over three years. We had to use some of the best bronze people we knew, the best stone carvers, and a community of women in Lost Hills, California, part of this farming community, to do the beadwork. It felt like important work because it was for a museum — and it was creating jobs.

CA: Where did the beads come from for The Strawberry Tree?

NH: We got them from a defunct factory in Murano that went out of business in 1982. We had to go into this factory with vines growing through it and puddles of water everywhere, and tarantulas and scorpions, and find these wooden boxes — the fact that they’re in wood boxes means they’re probably turn-of-the-century. We don’t know the exact age. But the factory had been in business since the early 1800s.

CA: On The Strawberry Tree after dark.

NH: We put it in front of the museum, where there’s a wall of open glass, because we wanted everyone to be able to continuously experience it. And it’s illuminated. I think the best experience will probably be at night through the window for someone that just happens to be walking by.

CA: Plans for your surreal Zoids, which will grace the back garden.

NH: Those are interesting works because they’re the shapes that we call Zoidbergs. Simon created digital sculpture, like skeletons with skin on top. These forms can be thrown into physical simulations that can interact with each other. We’re taking them and slamming them against each other, putting them on a turntable and spinning them superfast and just seeing what happens. And picking a moment that we think is poignant.

It’s taking the final expression out of our hands, because we’re talking about the fact that the viewer, in the context of artwork, is in fact projecting themselves upon the art. That is the value in art, when someone has their own experience with it and takes their own value out of the work. We don’t have any emotional motivation making the work, and the abstract value and the perception of the work is emergent. We have an eight-foot Emergent Zoidberg. Because the form itself is emergent, then the value itself is emergent to the viewer. Those are going to be in bronze in the back garden, with handblown glass and electrified.

CA: About your final body of work for the Nasher: Moon Towers, which stand guard outside the museum entrance.

NH: They’re based on moon towers in Austin. Do you know the story?

CA: Just that they’re from another era and very archaic and fascinating.

SH: There are only six of them left in Austin. Basically, they make perfect moonlight. We grew up half a block away from one. So, we wanted to make our homage to the moon tower. We have a couple installed in Los Angeles as public works. We have some publicly installed in China. Then Jeffrey Deitch showed a group of them in his L.A. gallery, but the ones for Nasher get a special patina. The exact ones that are going to Nasher have not been seen before. I believe those will be there for longer than the duration of the show, which is exciting for us.

CA: On your Austin roots. Which neighborhood did you grew up in?

NH: Clarksville. 12th and Blanco, that was our corner. You could see the Capitol building from our hill. Swede Hill is down the road.

SH: Lora Reynolds gallery is down the road too, which is cool.

CA: While we’re talking Texas, what was it like growing up in Austin? Were your parents creative?

SH: Our mom, Emily Tracy, was a screenwriter, and our dad, Berthold Haas, was a stone carver. He’s also a sculptor and painter. We worked with him as kids doing stone carving. Texas has a lot of limestone. In various houses in Austin, you’ll find something that we carved architecturally, but I don’t remember all of the spots.

NH: Our mom wrote for Seinfeld and The Cosby Show. She was an opera singer as well and sang for the Santa Fe Opera. Our older brother, Lukas Haas, is an actor. So, our household was super eclectic hippie. A very Austinite family, but to the max, in terms of the art around us. Everyone was playing music all the time. We were brought up to think creative. We had to learn how to balance a checkbook later in life, but we figured it out.

And then you could go further back … Our grandfather, Siegfried Haas, made bronze. He was a sculptor as well in Rottweil, a very small town in Southern Germany. So, we’re technically third-generation sculptors. Right now, we’re working in the early stages, but curating a show of our work along with our dad’s and grandfather’s, because there’s such a lineage of art.

SH: Our mom’s dad, our grandfather Paul Tracy, was a journalist at the Austin American-Statesman, which is cool — the closest to a structured job, but still a writer.

CA: You can’t make up a better family tree, informed by the idea of working with the hand.

NH: Construction is our most fluent language when it comes to expressing ourselves. That comes out in sculpting and material development. But, really, the meat of our job is storytelling. It’s about creating fantasy and space for somebody to dive into on their own.

If you read a great book, then go see the movie … Everyone’s been talking about Dune, right? The book is fantastic. You have an image in your mind of what it is. Then you go to the film, and sometimes you’re like, ‘Oh my god, they got it exactly the way I saw it.’ Or you say, ‘Oh, they didn’t quite get it.’ I think that’s what a writer does, or a musician or a sculptor like us: You’re putting something out there, some sort of media, for people to have a personal experience with. The adults around us and our family, we’re all investing in those types of jobs — to do things where you lead people into either alternative thought or dive into fantasy or lose themselves a little bit. I think we’ve carried that torch for sure.

“Haas Brothers: Moonlight,” May 11 – August 25, at Nasher Sculpture Center, nashersculpturecenter.org.

_md.jpeg)