Masterful Existential Sculptor Is Finally Getting His Public Due and Houston Gets to See – Giacometti Isn’t Just For Serious Collectors Anymore

Powerful Slender Figures That Leave More Than an Impression

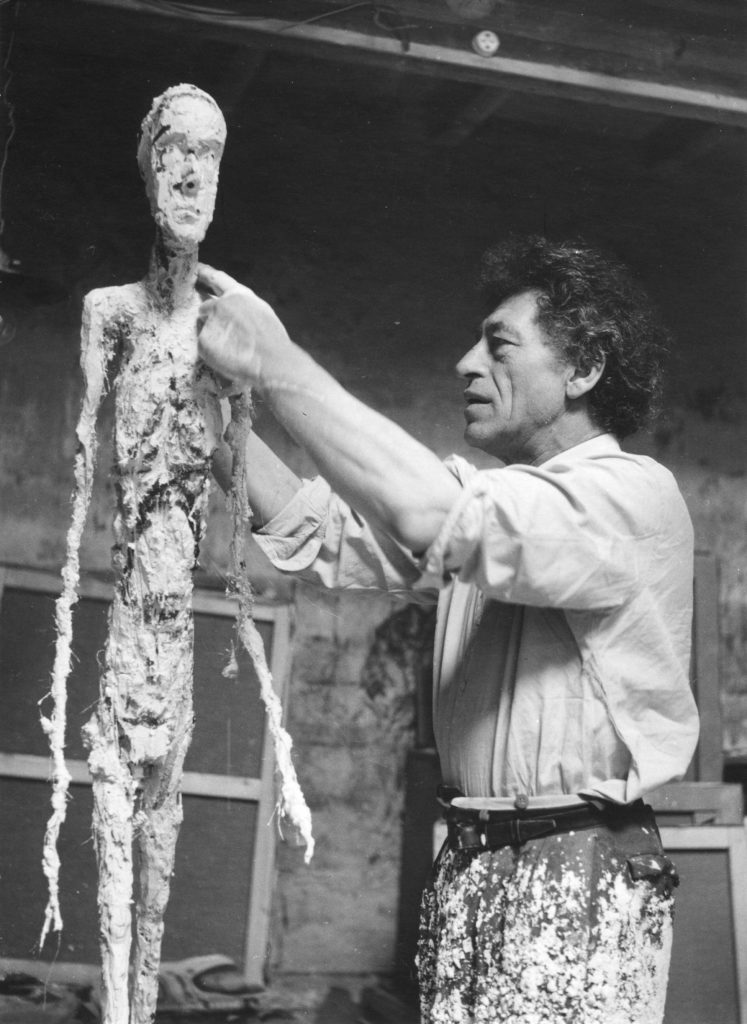

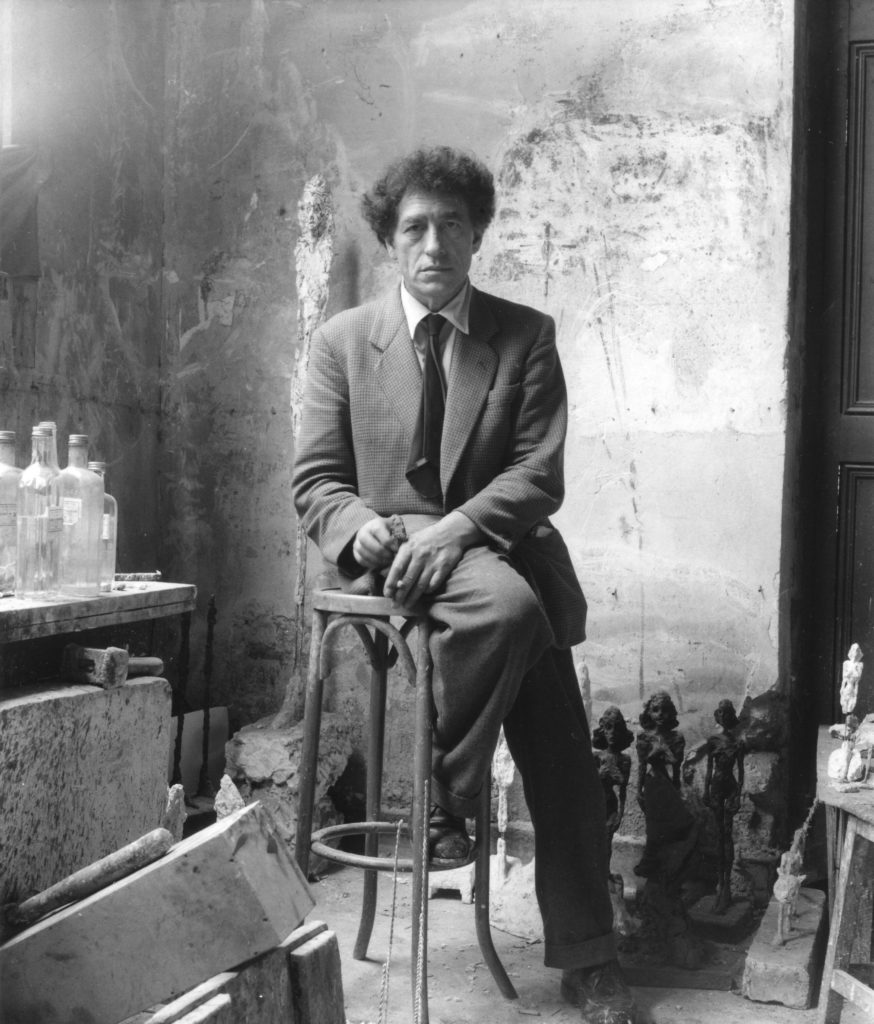

BY Leslie Loddeke // 12.20.22Ernst Scheidegger, Alberto Giacometti Working on the Plaster of the “Walking Man,” c. 1959, silver print on paper, Archives, Fondation Giocometti. (2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ProLitteris, Zurich.)

Having an existential crisis? Feelings of alienation, such as those French existential philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre described back in the 1940s, commonly arise during periods of global turbulence. The question becomes: How to deal with them?

The answer — or at least a little artful therapy — may be found more simply than you think. Maybe consider visiting a new exhibition featuring an acclaimed master of existentialist sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houstonians have a singular opportunity to better understand existentialism and explore its expression by a sculptor who perfected the art in the current MFAH exhibition “Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure.”

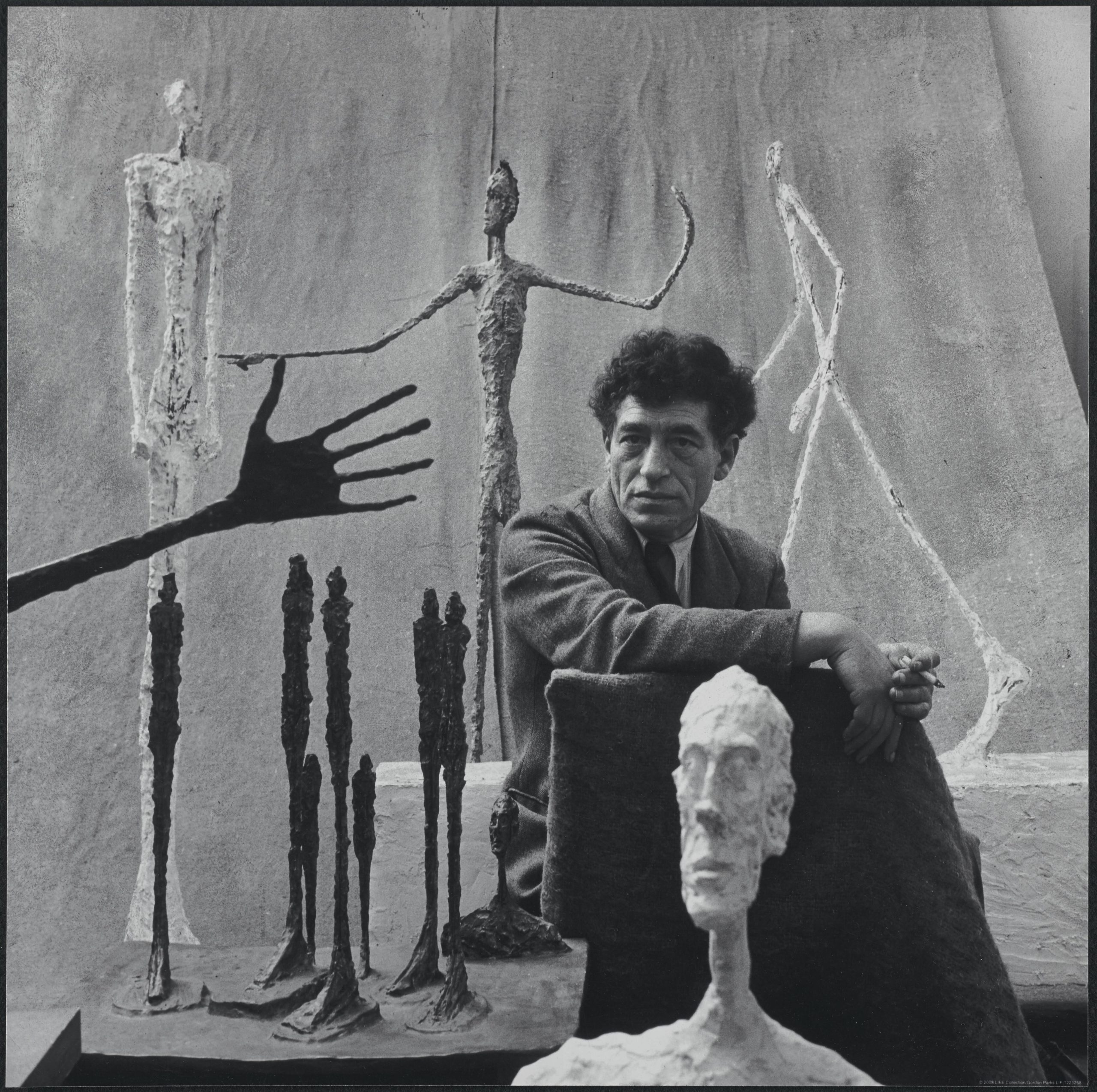

One of the most important sculptors of the 20th century, Giacometti (1901 to 66), whose works have long been prized by collectors, has been attracting increased attention in recent years with the general public getting greater access to his work through critically acclaimed exhibitions at major museums. Enhanced awareness and appreciation have been spawned by shows at the Royal Portrait Gallery and Tate Modern in London, the Guggenheim in New York and most recently at art museums in Seattle, Cleveland and now Houston.

Giacometti’s work became most closely associated with existentialism, a philosophy that questions the nature of the human condition by virtue of the emaciated, elongated figures he developed during the postwar period from 1945 to 66. Giacometti distinguished himself by reasserting the validity of the figure and figural representation at a time when abstract art predominated.

The MFAH exhibition focuses on Giacometti’s achievements during that period, when he developed the style reflecting the existentialist sense of alienation, doubt and anxiety pervading the aftermath of World War II with the world moving into the uncertainties of the Cold War period.

This well-informed exhibition of 60 masterpieces, co-organized by the Fondation Giacometti in Paris and the MFAH, is co-curated by Ann Dumas of the MFAH and Hugo Daniel of Fondation Giacometti.

A specialist in early 19th and 20th century art, Dumas holds dual roles as consulting curator of European art at the MFAH and curator of the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Those visiting the exhibition, generously spread out across the second floor of the Brown Pavilion in the Law Building, have ample room to examine each piece and read the enlightening explanatory labels, sprinkled with revealing quotes from Giacometti and Sartre, the sculptor’s literary contemporary.

As you roam through this large exhibition at MFAH — especially if you’re short on time — be sure to watch for such standouts from Giacometti’s fruitful postwar period as “The Nose” (1947), “Three Men Walking” (1948), ‘The Cage” (1949), “Tall Thin Head” (1954), “Seated Woman” (1956), “Walking Man” (1960) and “Tall Woman IV” (1960). With the exhibition on view at the MFAH until February 12, there’s still ample time to peruse the artistic journey so comprehensively presented in various forms.

“The Nose” (1947) portrays a suspended head whose thin, grotesquely elongated nose extends through the bars of a surrounding cage. This arresting sculpture was partly inspired by Giacometti’s shocked reaction to the death of a man who lived next door to his studio in Montparnasse. To my eye, the specter evoked the Venetian carnival mask of the plague doctor.

Emblematic of the alienation of existentialism is the sculpture entitled “Three Men Walking” (1948), in which “multiple figures walk through an empty space in a city square, each in a different direction, disconnected from one another,” as the accompanying label notes.

The majority of the works in the exhibition came from the Fondation Giacometti in Paris, which enabled the MFAH to provide a “very rich presentation” that gives Houstonians who may have seen only a few of his pieces a chance to really discover this greatly admired artist, Dumas tells PaperCity.

Representative of their time and place, Giacometti’s postwar pieces exude a sense which some may interpret as “mysterious and enigmatic,” but Dumas stressed that “it would be wrong to read something dark into them.”

She quoted Sartre’s observation that Giacometti’s works could be “like Assumptions” in Christian art, “rising up,” as seen in “Woman of Venice III” (1956), while the “tall, proud stance” depicted was “evocative of courage and hope.” That “proud stance” is particularly evident in the towering figures of the 1960 “Walking Man I” and “Tall Woman IV.”

Moreover, Dumas points to the “rugged surfaces” of his sculptures as expressive of resilience – a key word to which many Houstonians can relate from surviving periodic hurricanes and floods, not to mention those overarching global challenges.

The Giacometti Story In 12 Sections

Walking through 12 thematic sections, visitors can learn a wealth of information about Giacometti and the development of his signature style. The show encompasses not only his sculptures but his paintings and drawings, as well as photographs and other markers on his path toward achieving “the ultimate figure.”

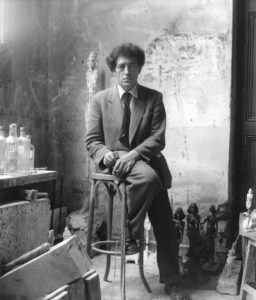

Born in a little town near the Italian border in Switzerland, the son of a post-Impressionist painter, Giacometti moved to Paris in 1922 at age 21 to study with the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere. Four years later, he began renting a tiny, ill-equipped studio in the district of Montparnasse, which he maintained for the rest of his life despite increasing fame and accompanying privilege.

The exhibition opens with “Paris: Life in a Studio in Montparnasse,” featuring a black-and-white photo of his small, shabby studio. It’s an excellent introduction to Giacometti, illustrating the insular perspective of an artist who spent his life in his head, finding rewards in his work rather than the exterior world around him.

One of Giacometti’s earliest influences was his painter-father Giovanni, whose studio he began working at in his teens. He soon developed an interest in African art, reflected in “The Spoon Woman” (1926) which was shown in 1927 at the Salon des Tuileries in Paris. Jacques Lipschitz and Fernand Leger served as influences on Giacometti’s early Cubist sculptures, the informative Foundation website notes.

In 1931, Giacometti joined Andre Breton’s Surrealist movement after the group’s attention was drawn to his “Gazing Head” when it was first shown in Paris in 1929. However, his increasing obsession with sculpting the head in a more realistic style caused his break from the group as he returned to working from live models.

Gordon Parks Foundation)

Over the next decade, he “made and remade the same heads for months. . . until I arrived at a single head, the key to all the others,” as recounted in a panel quote which describes Giacometti’s dogged dedication to perfecting his work.

Further illustrating that, a short film from Swiss photographer Ernst Scheidegger showing Giacometti as he was working, totally engrossed, on a sculpture, is part of the MFAH exhibition. In the brief clip from the 1964 documentary, we were able to see in action the intensity of Giacometti’s concentration on continually improving his work, particularly on the “gaze” of the eyes of the head which he kept molding and remolding with his fingers.

During World War II, Giacometti left Paris for Switzerland. He spent several years working in a small hotel room in Geneva, creating figures that were so tiny, legend has it that later, he brought them back to Paris in a matchbox.

In the section “Into Thin Air” we see how, in the 1940s and 1950s, Giacometti emphasized his intention that his figures appear as if viewed from a distance by elongating them into ever-thinner shapes which almost seem to vanish from a different perspective. He wanted viewers to see his works in their essence, without context, rather than being diverted by details that would be evident in close proximity.

A turning point came when Giacometti met Sartre in the early 1940s, when the sculptor’s work became associated with existentialism. “Existentialism posits that, finding ourselves alone in an absurd universe, we experience anxiety, confusion and alienation, although we can resist these forces through individual action,” notes “The Human Condition” panel, citing Giacometti’s sculptures of figures trapped in cages or walking in different directions through empty city squares.

Meanwhile, the literary corollary emerged in Sartre’s Nausea, the existentialist philosopher’s 1938 novel centered on Antoine Roquentin, a young writer overwhelmed with nausea at the emptiness and banality of his existence.

Exhausted from his research on a biography that suddenly seems meaningless, Roquentin finds inspiration in the voice of a singer accompanied by a saxophone on a record playing in a cafe. Imagining the creative suffering of the song’s composer and singer, he begins to consider the possibility of a similar salvation for himself, through a different artistic path.

“Can you justify your existence then?” Roquentin tentatively asks.

Therein lies the question raised for us by this well-thought-out exhibition. And perhaps some of the answers.

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)