In the Eye Of His Own Art Storm — Artist Howard Sherman Fights To Not Be Pinned Down With Shows From Houston To Berlin

Embracing The Creativity Of Controlled Chaos

BY Alison Medley //Firing pistols at a bare naked wall is one of Howard Sherman's works.

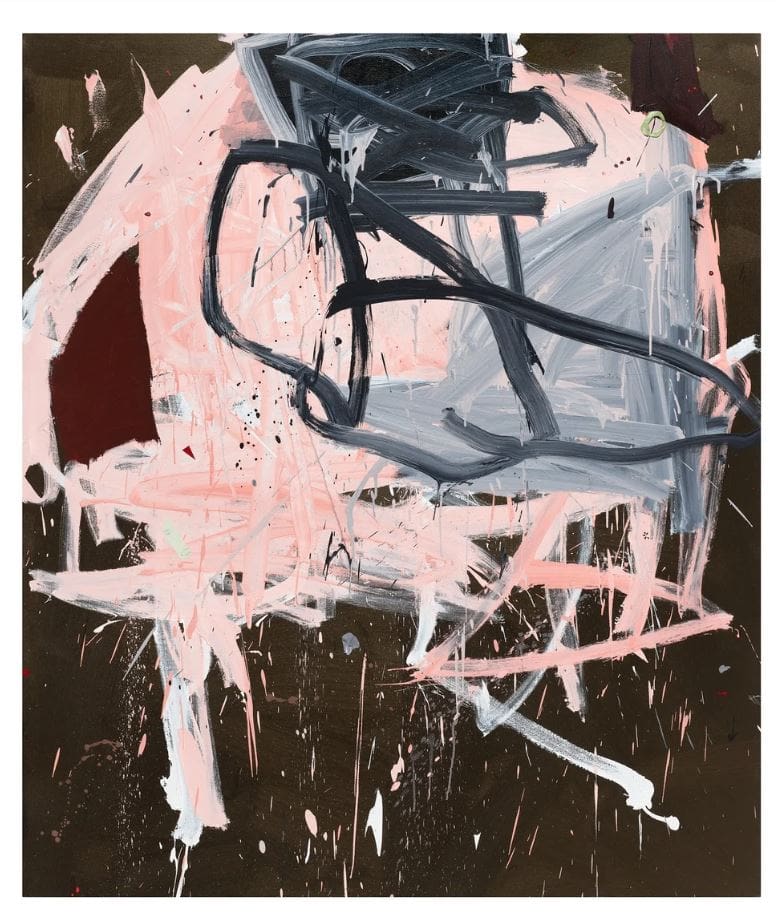

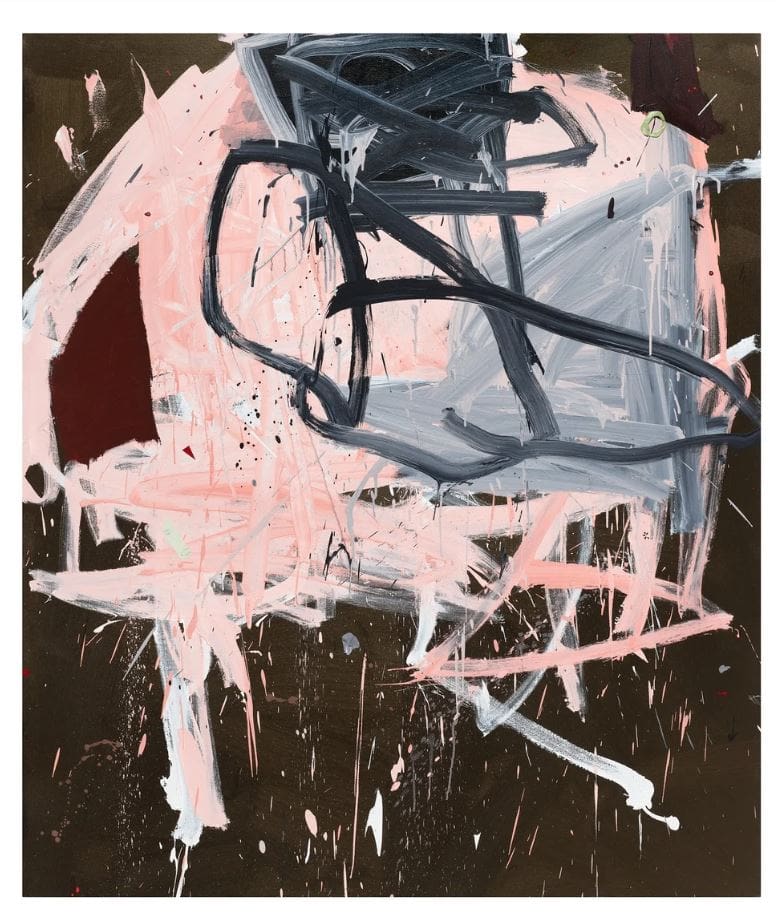

On a turbulent, storm-racked afternoon in Houston, Howard Sherman stands between two paintings that churn like opposing fronts: a brand-new canvas still radiating with wet energy and a 2011 work whose frenetic humor once announced him to the Bayou City’s art scene.

Sherman’s studio feels less like a gallery than the eye of a storm. He has just sold a 100-inch painting.

“These are hard to sell,” Sherman shrugs, half grateful, half wary. He is eager to preempt a mislabel that trails him around. “Just guard one thing,” he emphasizes. “I’m not an abstract expressionist. Really, I’m a contemporary artist.”

Labels make Howard Sherman itchy, but lineage matters. Sherman is quick to say he’s in dialogue with art history. “There’s all kinds of it in the work, including abstract expressionist,” he notes. Yet he’s pushing it somewhere idiosyncratically his own. He points to a canvas that landed on the cover of a Texas art history survey a few years back and acknowledges the honor.

“I’m proud to be part of that story here,” Sherman says. “But I like to think I’m in the contemporary conversation based on what I’m making, not just a historical one.”

is hard to define.

Howard Sherman, The Busy Artist

Three exhibitions mark this fall for Sherman. His work is currently on view at the Cat Spring Collection Exhibition at 4411 Montrose. While across the Atlantic, Sherman is joining two group exhibitions at Galerie Kremers in Berlin and Galerie Art Cru which is opening this September.

This contemporary conversation has a new anchor: Howard Sherman, a recent monograph with a foreword by critic David Cohen and an essay from Alex Bacon. Cohen once described the invitation of Sherman’s big canvases as a kind of anarchy. Sherman bristled at that. Gently.

“I think it’s fine he used anarchy, but I don’t love the implication that there’s no thought, no order, no formal rigor,” Sherman tells PaperCity. “A friend calls it controlled chaos. There are passages that are intentionally chaotic, and then they’re roped in by structure. So the composition actually coheres. If it’s just noise, the painting’s forgettable.”

Sherman’s studio talk toggles between the offhand and the precise. He’ll crack a joke, then zero in on a corner of a painting to show exactly where a hard-edged shape reins in a splatter.

“I’ve always been interested in the collision,” he says. “Spontaneous, gestural mark-making right next to something meticulously taped and cut. Your hand moves differently. It’s like cursive versus a scribble. Same tool, completely different part of the brain.”

His process starts with a paradox that doubles as an aphorism.

“The plan is to have as little plan as possible,” Sherman says. “It’s not blank spontaneity. There’s always some subconscious plan — color relationships I want to work with. But it’s call and response. I make a mark that affords the next mark that affords the next.” He describes beginning one big canvas with a single splatter that ran across the top and then “slowly editing it out” as the composition revealed itself.

“The trick is to make it look slapdash and carefree,” he says. “While the whole thing is deeply resolved.”

Acrylic, Canvas and Marker

leaves an impression.

Not being “precious” is part of Sherman’s work ethic.

“If the idea’s good, you’ll find it again. I’ll sometimes shoot a photo and trust it’ll come back,” he says.

Over time that trust becomes vocabulary with recurring forms, moves and temperatures. “After this many years, you have a specific visual language,” Sherman notes. “That’s how the work hangs together across bodies. Same sentence, different verbs.”

Sherman is literal about that metaphor. Gesturing between the 2011 piece and the fresh one, Sherman dives into the nuance.

“Back then that black marker line was a noun. An outline, a thing. Over here it’s a verb. The language is still there. I’ve shuffled the parts of speech. I was showing off in 2011,” he says. “Look how much I can do. Now it’s calmer. Still aggressive, but more singular, more distilled.”

If his paintings carry whiffs of cartooning — looping contour, deadpan wit — it’s earned. As an undergraduate, Sherman drew a daily comic strip and self-syndicated it to papers around the country before ditching the deadline grind.

“It taught me discipline and economy of line,” he says. “When your strip is reduced to stamp size, every mark matters. That sensibility never really left.”

Discipline, for Howard Sherman, isn’t abstraction’s enemy. It’s the scaffold for improvisation. His references take their cues from jazz wizards Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans.

“Those guys made everything feel improvisational,” Sherman says. “But, it was built on rigor and practice. That’s the balance I’m after.”

Sherman winces at the notion of the artist in the midst of creation, feeling it’s much too romantic. “Most of the time I feel like I’m grinding it out,” he says. “In the arena, taking blows and dishing them out. But that’s how you give yourself a chance at bona fide discovery.”

Using Graffiti In a Different Way

Recent discoveries have come via spray paint, an old tool turned new ingredient.

“In 2007-08, I was literally tagging across the surface,” Sherman says. “I got lumped with graffiti writers — which I didn’t want — and I stopped using it for years.” Lately he sprays on paper or raw canvas, then collages those volatilized passages back into paintings.

“Friends in Marfa said they felt ephemeral, like clouds, or like black-and-white photography,” Sherman says. “That clicked. It was a new word in my vocabulary.” He grins. “Sometimes you don’t get a whole new sentence,” he notes. “Just a new adjective. But that can push everything forward.”

The adjective metaphor doubles as an ethic against repetition.

“I don’t want a product line,” Sherman insists. “I’ve never had a home run item that just flies off the shelf.” Sherman motions to a row of crisp works on paper.

“People assume these will float my rent,” he says. “They don’t. Weirdly, the bigger ones sell more often.”

Sherman is not resentful — just wary of the trap. “I’m not the guy people call for ‘Do it in blue and put a kitty cat here and a dog there,’ ” he says. “I’m an artist making paintings and drawings. Full stop.”

shows how he uses spray paint today.

If Sherman’s content is brash, his working life is unromantic. He moved back to Houston from New York five years ago.

“New York’s a pressure cooker, and I wanted that pressure,” he says. “I miss it. In a perfect world I’d split my time. But Houston let me breathe. Cheaper, easier to get around. The weight came off, and that helped the work.”

The Bayou City’s growth pangs — rents rising, studios scarce — have chased him into a storage unit for overflow. Still, the location suits him. He mounted a Montrose popup last year.

“New people came,” Sherman says. “It reminded me how big Houston is,” He keeps ties to a gallery in Berlin, and is angling for Miami later this year. “I just want the work out there more,” he adds. “And I want the opportunities to get better.”

Getting better is as blunt as Howard Sherman makes it sound.

“If you show up every day and work at something, you get better,” he says. “Artist, plumber, dentist. It’s the same.”

He taught drawing to undergraduates in grad school and still drills himself on fundamentals: composition, figure/ground, the cadence of shapes.

“Most artists can’t work by staring at the ceiling for three weeks and outputting everything in a weekend,” Sherman says. “You show up.” He can be unsparing about the difference between amateurs and pros.

“Studios are full of people who work Sundays,” he says. “Where are they the other six days? It shows in the work.”

Sherman is equally rigorous about ideas. He cites the late critic David Hickey’s advice to study art history, not just technique. “You learn the rules to break them,” he says. “A deep knowledge of what’s happening now and what came before lets you compensate for your weaknesses and reiterate your strengths.”

Acrylic, Canvas, Spray Paint and Marker, 70x 60, 2022

The comment isn’t self-deprecating so much as practical. Sherman is relentlessly focused on what a painting does. “People remember how things make them feel more than how they look,” he says, paraphrasing Maya Angelou. “When a painting starts to feel different, that’s when you know you’re onto something.”

In person, Howard Sherman’s work is all attack and afterimage: blown-out whites, bruised greens masquerading as black, a spray-paint fog stapled to bright forms. The surfaces can be scarred and comic at once, masking-tape trompe-l’oeil next to a cartoonish contour that refuses to resolve into a figure.

“I want it to look like it just happened, and then keep rewarding a slower read,” Sherman says. He’s allergic to fuss, but he edits like a surgeon. “A lot of the thoughtfulness comes in the editing,” he notes. “You have to know when to stop showing off.”

He laughs at his younger self. “I was busy” is how he puts it, without disavowing the work. He loves that 2011 painting. He just doesn’t want to make it again. The new ones compress more.

“Everything’s a little more distilled and simpler,” Sherman says. “Still aggressive, but calmer in its bones.” If critics hear “belligerent informality,” so be it. He’ll keep arguing for the formal armature underneath. And if the market keeps favoring the biggest pieces, Sherman will keep making them — when the painting demands that scale.

is another memorable work from Howard Sherman.

The day winds down the way it began, mid-sentence. Sherman is summoned back toward the big canvas, as if Theolonious Monk were playing somewhere just beyond earshot, setting the tempo.

“I don’t have a boss, and I’m doing exactly what I want,” Sherman says. “It’s fucking hard. He grins, unbothered. “But you show up, you make a mark that affords the next mark, and you try not to be precious. If you’re lucky, a new adjective shows up

“And then you see where the sentence wants to go.”

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)