Romancing the Stones — Insider Tales, Challenges, and Aha Moments from the DMA’s Blockbuster Cartier Exhibit

In Conversation with the Dallas Museum of Art Curator Sarah Schleuning

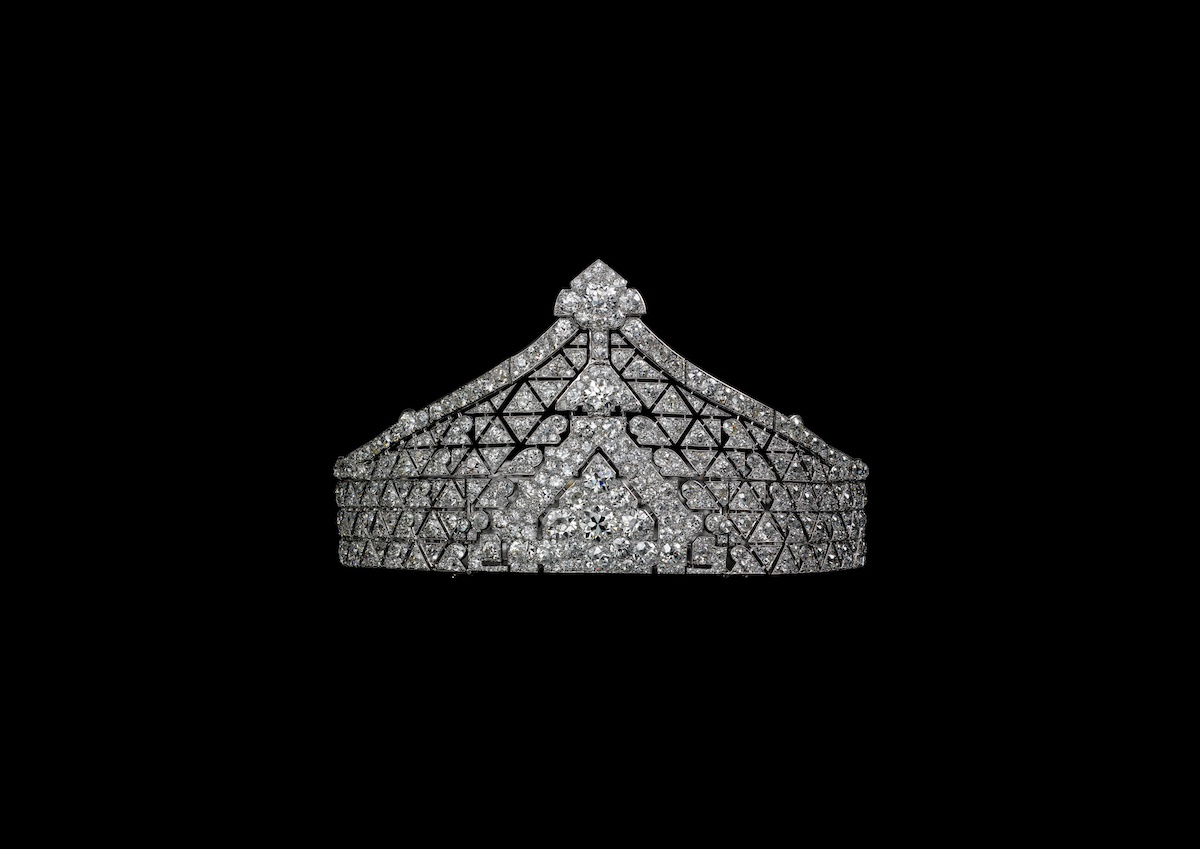

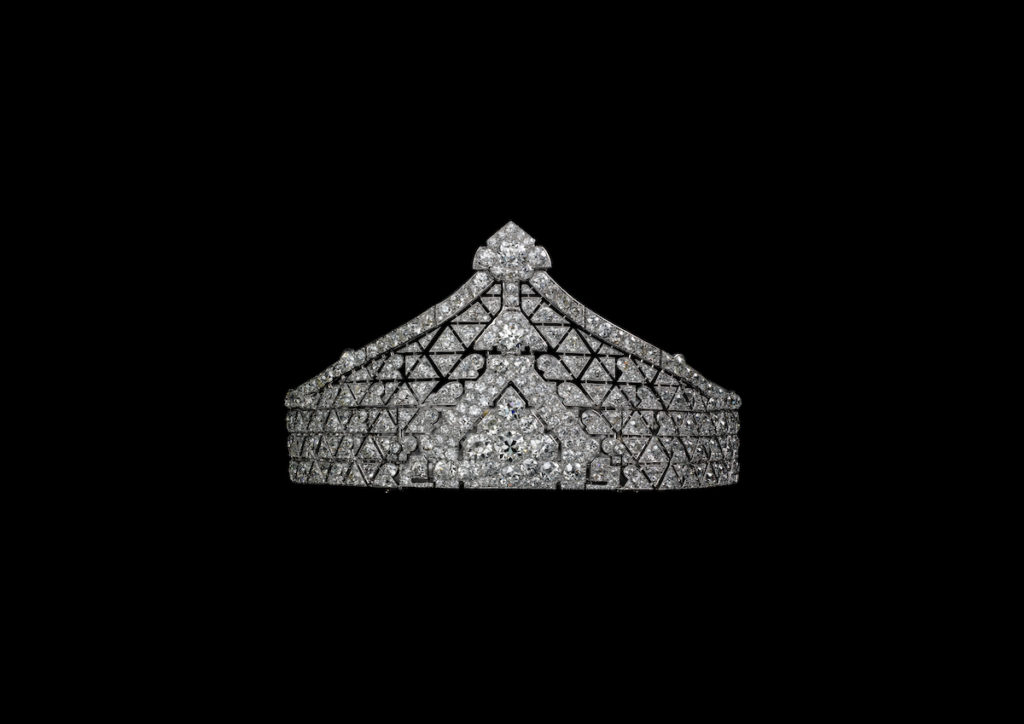

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 06.16.22Head ornament, Cartier New York, circa 1924. Marian Gérard, Collection Cartier © Cartier

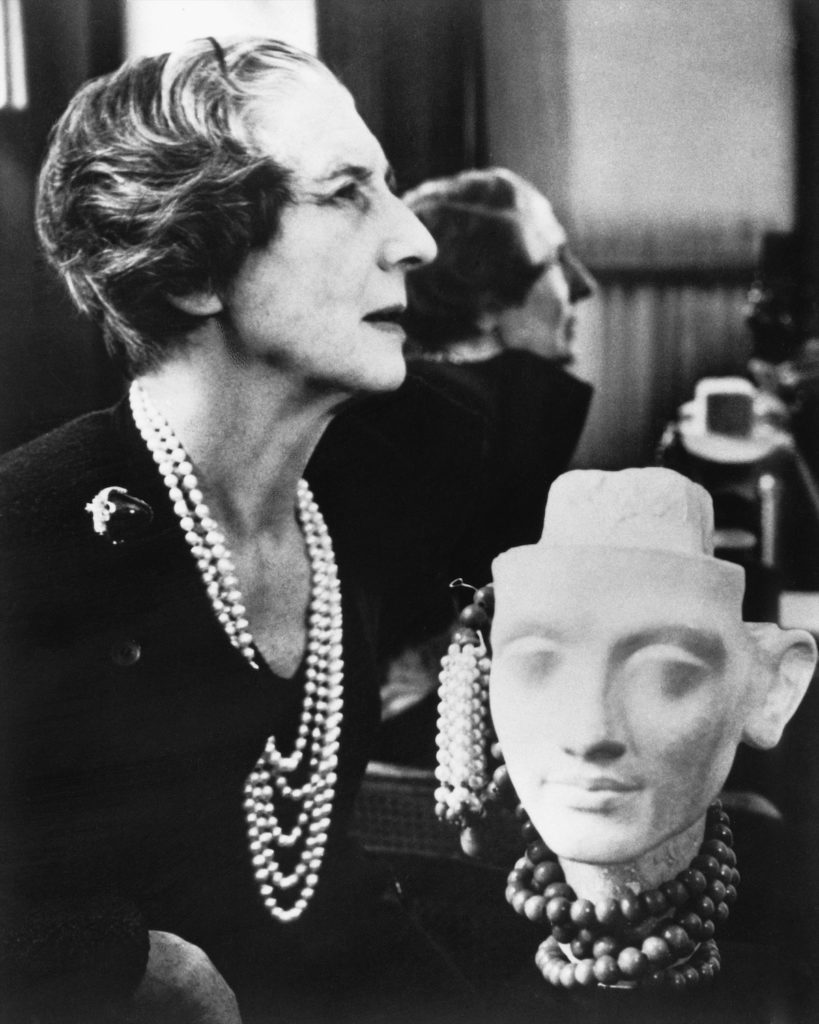

Catherine D. Anspon speaks with Dallas Museum of Art’s Sarah Schleuning, one of four international curators of “Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity,” which opened at the DMA on May 14 (through September 18). Schleuning reveals insider tales from the archives of Cartier, and how the remarkable Cartier creations that sprang forth from the 1910s onward were inspired by sumptuous, centuries-old Islamic architecture, decorative and fine art, and jewelry.

Tell us about the making of this magnificent exhibition co-organized by the DMA and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD), Paris, in collaboration with Musée du Louvre.

Sarah Schleuning: I have had the privilege of working to bring this show to life over the last four years, spending the first half of this time traveling back and forth to Paris and Geneva, London, and New York prior to the impact of COVID-19. In the years before the pandemic, I spent much of my time exploring the main Cartier archive in Paris, in addition to the archives in New York and London. With an undergraduate degree in cultural anthropology from Cornell, my fascination has always been in design and structure and pulling on the themes of cultural anthropology: intent, material culture, why people own things, why they keep them, what they mean, what they signify. Once the pandemic hit, we continued our partnership and planning over Zoom, overcoming the challenge of not being able to see the objects in person.

Your curatorial approach to conceiving this exhibition.

SS: To me, this show has always been about looking at Cartier through a lens of individuals and what they look back at, what they absorb, how that affects what they make — the cyclical nature of it. You see contemporary designers at Cartier looking back through multiple layers of information and ideas. It’s interesting, because it’s about creativity and what sparks creativity, and how sources float through people’s creative ideas, and how they show up in different ways. I think part of the idea of the show was to trace and name those potential origins and say that all creativity is sparked by other things. Critical to this project was having two Islamic curators and two design curators, who each brought diverse points of knowledge to build the narrative of what these Islamic collections meant.

“Cartier and Islamic Art” and today’s world. What’s modern about this exhibition?

SS: To put it in contemporary terms, the advent of photography and magazines was the Instagram of the moment — of the 19th century and turn of the century. To me, going through these research materials is very much like shuffling through Instagram. Louis Cartier, Jacques Cartier, and all the designers at Cartier were inspired by ideas found in these photographs and portfolios, and by exhibitions they saw.

Curatorial team.

SS: Judith Hénon-Raynaud from the Louvre, deputy director of Islamic art. She had done some research on pen boxes owned by Louis. Évelyne Possémé is curator of jewelry at MAD, and Heather Ecker is our former curator of Islamic Art at the DMA. And me. I say four-plus because we had tremendous help from Pascale Lepeu, the curator of collections at Cartier, and Violette Petit, head of the Cartier archives. Cartier providing access to their wealth of knowledge and holdings continues the Maison’s desire to encourage curiosity and scholarship.

Was there one Aha! moment when you decided, “Okay, we’re going to do this show”?

SS: There has long been talk about this idea of the influence of Islamic art in Cartier. I think it initially came about in a conversation. We would go to Paris and have three- or four-day workshops where we discussed: “Is there enough material? What would that story be?” What was interesting were our conversations about motif. We would look at certain pieces and say, “Is that the Japanese wave motif, or is that the Islamic scale pattern?” We would look at the Cartier library and think, ‘Well, what was Louis Cartier looking at? What did he have access to?’ We can tell Louis saw these things because they were in his library. He put little Xs by them. He marked things as being of interest. Then you see these ideas turn up in Cartier works.

Cartier and the Maharajahs.

SS: Some of these jewels were specifically made for wealthy Indian clients, so these jewels were not a westernized view for a westernized public. Many times, Indian clients would come in and say, “These are my family jewels, but modernize them. I want something that is of this moment, that links the past to the present.” There’s a lot in this show of what Cartier refers to as apprêts — taking other pieces of jewelry and incorporating them into new jewelry. Sometimes the original jewels were lightly touched; other times, it was a more intensive integration. I think the idea of resetting the stones or combining pieces of jewelry is interesting — honoring history but modernizing it to taste or interest of a particular client.

The roles brothers Louis and Jacques Cartier played.

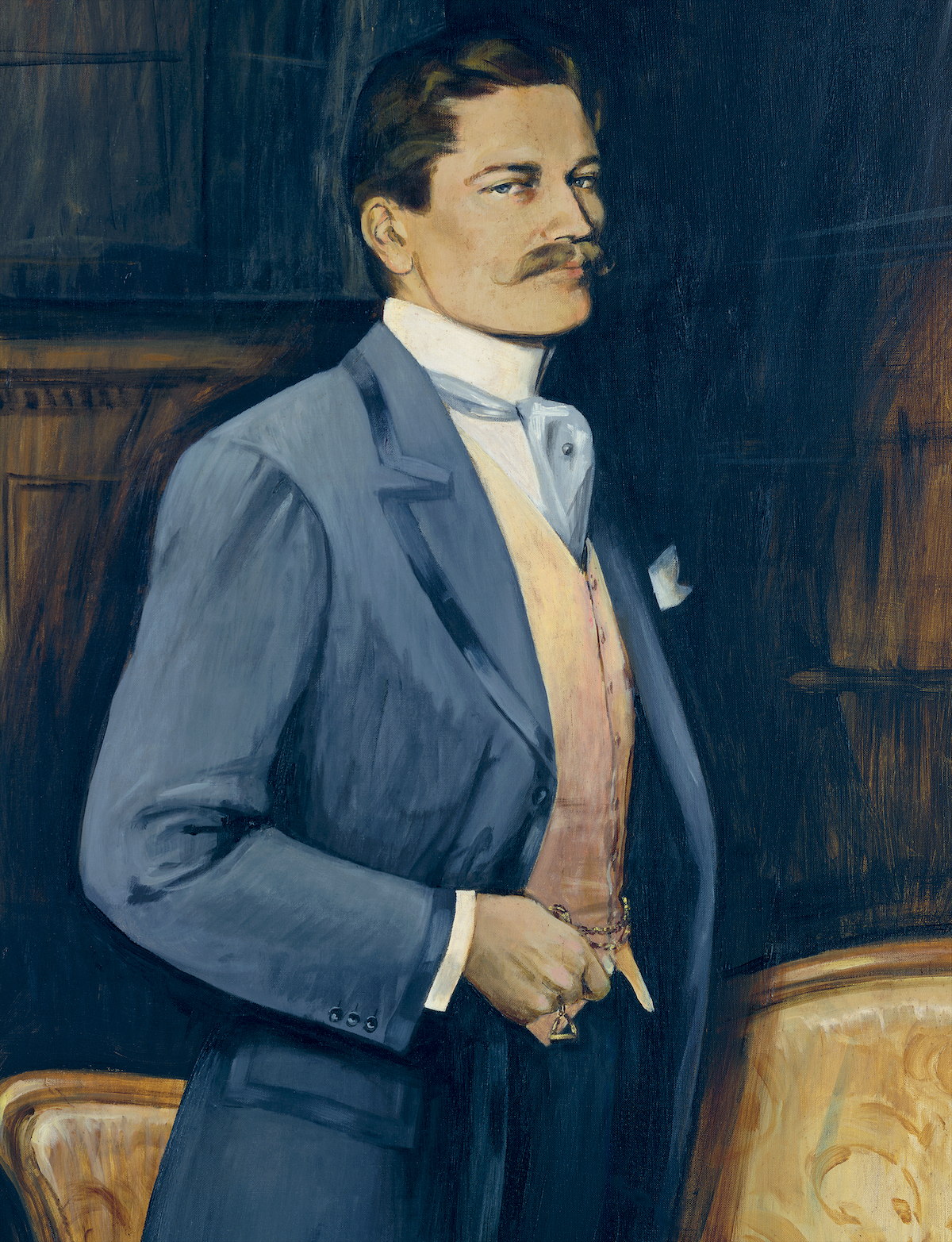

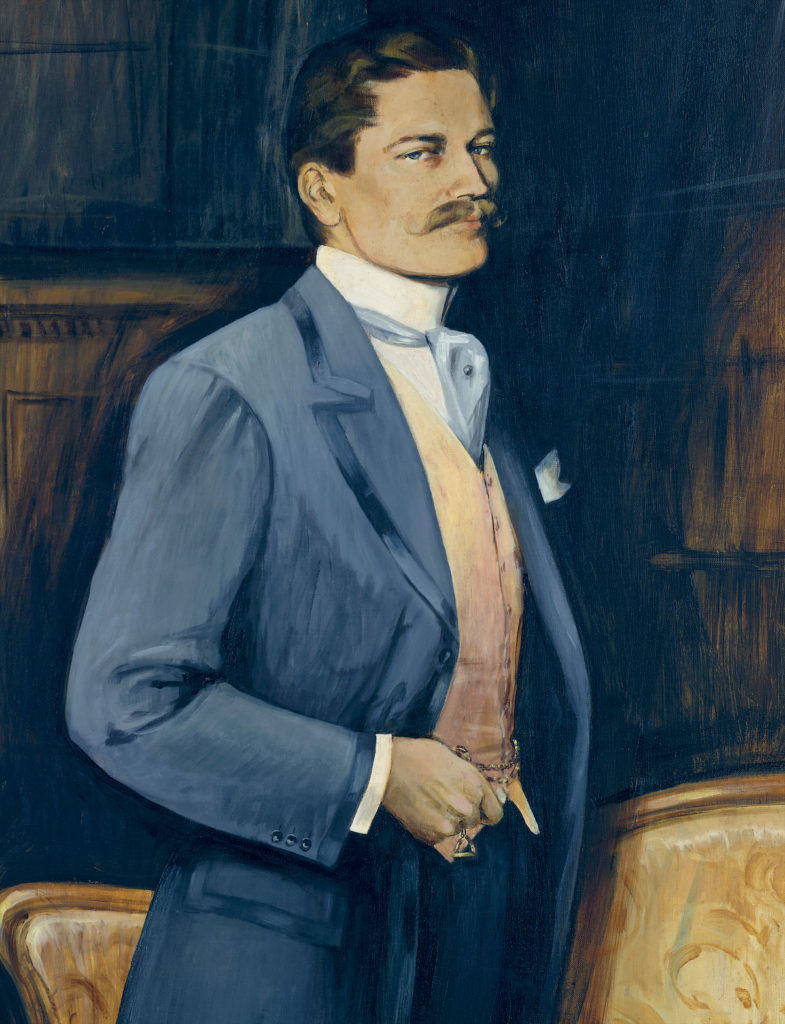

SS: Louis was the leader. He ran the Paris office, which is central, the main office. All roads lead to Paris. He was an omnivore. He was curious; he was investigatory. He had a very keen eye, and you can see that he pored over his books. He picked things that were interesting. And you sense that everything was interesting to him. He was looking for shapes and forms, and how those things could be made into jewelry. There also seems to be a tremendous sense of generosity and the desire to share information. Part of why we know what art and objects he collected are is because he shared them by lending them to exhibitions. And he collected everything from Persian pieces to contemporary portfolios of Islamic art. He was also assembling a study library accessible to his designers. That, to me, speaks not only of his own curiosity but also how he cared about sparking other people’s curiosity.

The curatorial team did a great job piecing this together. We know certain things because Louis Cartier was listed as the lender. Islamic art installations like the 1903 Paris and 1910 Munich exhibitions inspired Louis to personally collect. In the 1912 Paris exhibition of Persian miniatures, works shown in these early exhibitions are presented again, but now ascribed as part of Louis’ personal art collection.

The zeitgeist of this time.

SS: It started with a 1903 exhibition in Paris and a 1910 exhibition in Munich, which marked the shift to the rise of the discipline of Islamic art, moving away from the concept of orientalizing. This is how Louis became exposed to Islamic art. In that moment, there was a total fascination in Paris; the zeitgeist became the Ballets Russes and the ballet Schéhérazade, which is a modernized version of One Thousand and One Nights. You can tell there was a Persian-mania.

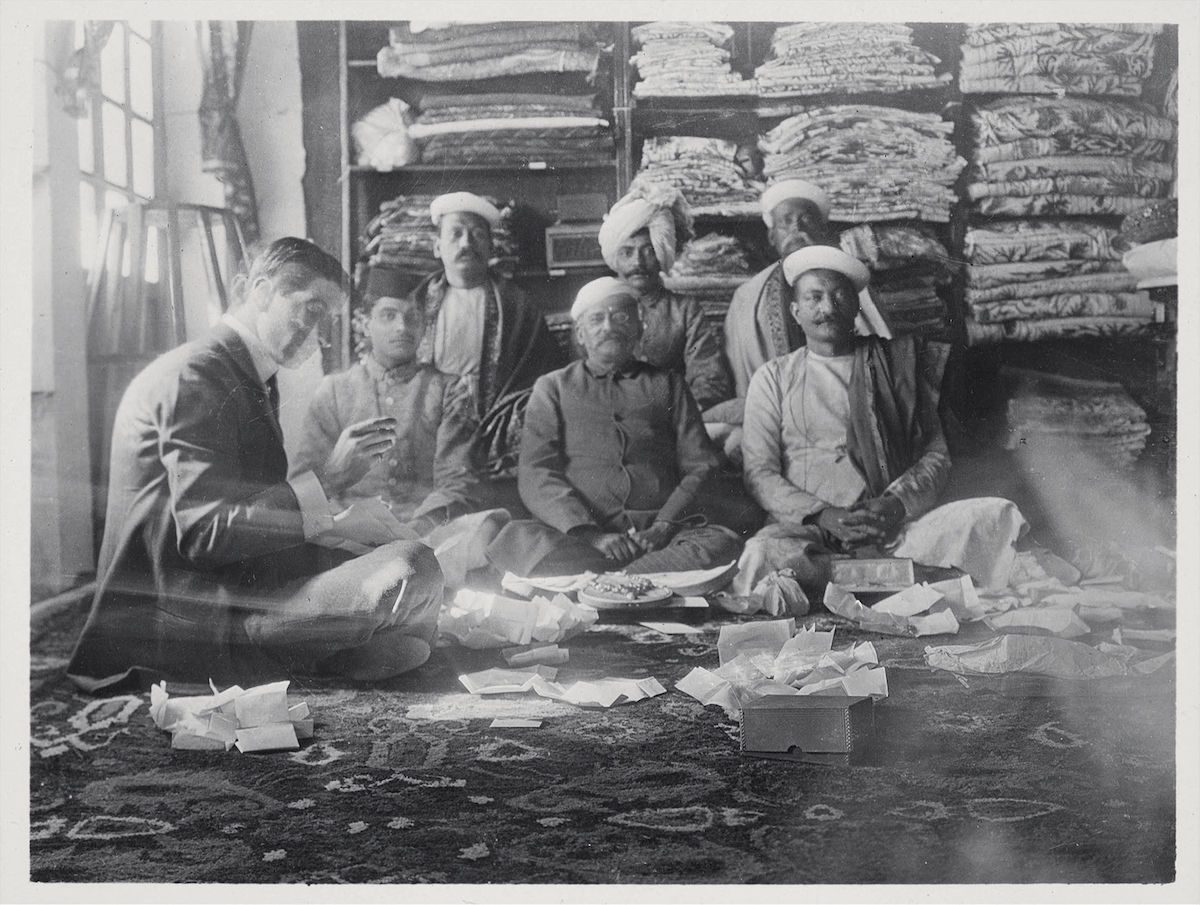

I think Louis was interested in the content and what that meant, and in the Islamic form. Jacques was more adventurous. He loved to travel and showed a tremendous acumen for pearls and precious stones. He did a big trip in 1911 when he went to India and Bahrain and came back with photos for the archive, as well as stones and pearls and jewelry. There were exhibitions that went to New York and Boston that were mixtures of historic Indian jewelry and more contemporized versions. You begin to see that the language in Cartier catalogs changing from presenting to adopting to transforming. They moved from restringing jewels to modernizing, then finessing the jewels while keeping elements of the original.

Emblematic object for you.

SS: I love the bandeau that’s coral and onyx (Cartier, Paris, 1922), because it’s a little piece of architecture worn on your head. It was constructed with the same care and craft in which the mosques were constructed in the past. It’s so modern, and the color combination and that sleekness … It’s very cool from the back, too, because it’s pinned to a tortoiseshell comb.

Exhibition challenges.

SS: How to make the richness of diversity of material come alive. We need to think about what connections people are going to make, and how they’re going to interpret a tiny plaster cast or a brooch. What we’re trying to set up — and what will be magical — is that people will engage with and look for different motifs or forms. There are so many ways to see this exhibition. Something I’ve been craving from being on lockdown for so long is to see things. To explore ideas through actual objects, to see the three- dimensionality of these things — when things get flattened, they are perceived one way. What happens when you take columns from architecture and try to imagine them on a tiara. How do you shrink it down? It’s very interesting on many different levels.

Cartier was an early globalist.

SS: I love the idea: how things move across scale and material and time. You’re drawing threads from architecture to a tiara. Things can connect in the most interesting ways. You could take the outline of a finial, and that gets twisted and shaped into the way a handle is made or a small detail on a little brooch. To me, it’s continuing to expand the possibility for people. I will say, as with every project, there is still much left to unpackage — we pushed the narrative forward, but there’s still so much to uncover.

Parting thoughts.

SS: It was fun with the four of us, because each curator had a unique perspective. At the DMA, we expanded our thinking because MAD is a decorative arts museum; we are more than just that. I think it’s important to think about the role museums play. The idea of saying to yourself: ‘Wow, here we are 100- plus years later, showing the same object that was shown in 1903.’ It’s exciting for me to show these things again, and to hope and wonder what will come out of this exhibition. It’s been an incredible project about collaboration — collaborating with other curators, collaborating with Cartier and with other institutions, and then to collaborate with exhibition designer Elizabeth Diller and her team at Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

_md.jpeg)