Ethan Hawke Sticks Up For Texas, Reps Beto and Turns a Dead Country Singer Into a Legend: Hanging With a Movie Star in Houston Who Just Wants to go to an Astros Game

BY Chris Baldwin // 08.27.18Ethan Hawke may be a well known Hollywood name. But that didn't mean it was easy for him to get the funding to make Blaze.

Ethan Hawke appreciates Houston. He’s grateful to it in many ways. He’s shot two of his most iconic movies here at two completely different times in his life — Reality Bites and Boyhood.

But Hawke wishes he knew the city better.

“In truth, I’ve never spent as much time in Houston as I’d like,” he says. “I’ll always have incredibly happy memories of filming Boyhood around here and truthfully, even Reality Bites was a lot of fun. The Menil museum gallery… I really like that gallery and feel like it’s a special place.

“Houston’s strange. There’s all these little magic pockets. Areas that people don’t know about.”

Hawke happens to be sitting in one of those spots at the moment — Rockefeller’s Hall, the reborn, almost tucked away music venue on Washington Avenue that’s something of a gussied up honky tonk. Hawke and Ben Dickey, the unlikely star of the new movie he directed called Blaze, are sitting around a small table meant for two with me, talking about their underdog passion project.

It’s an unusual setting for a movie press tour. These things are typically done in suites of hotels like the Four Seasons. But Blaze is an unusual movie — a film about a decidedly unfamous musician. And Hawke is determined to promote it in a fitting spirit.

Take the idea of opening the movie in Texas. That’s just not done. But as far as Ethan Hawke was concerned, Blaze couldn’t be done any other way.

“People weren’t sure what we were doing,” Hawke tells PaperCity of Blaze opening in Austin, Houston and Dallas weeks before it ever hits New York City and Los Angeles. “It was an idea that actually came out of Sundance. And it came out of the fact that I was talking to Jonathan Sehring, who’s head of IPC, and he loved the movie and he was like ‘How would we release this movie? How would we do it?’

“Well, it’s folk art and it’s a grassroots movie. And it just kind of came out of my mouth. We should open in Texas. It just popped in my mind.”

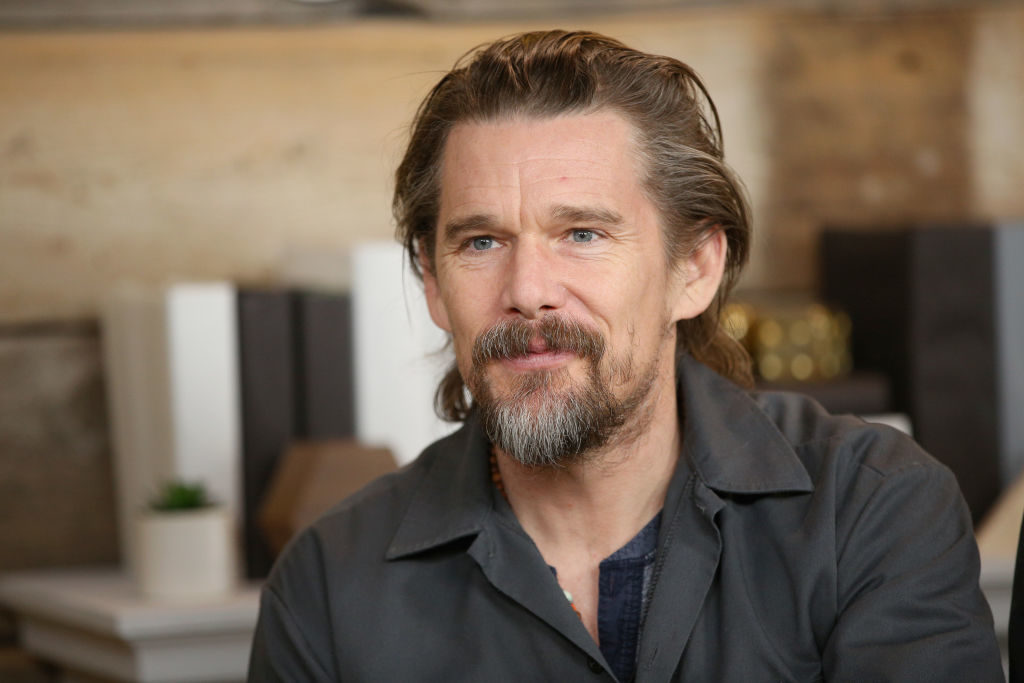

Hawke looks like anything but a Hollywood heartthrob when he’s promoting Blaze. He has a goatee and he’s not trying to hide the gray in it. His hair is often a little long — and some might say a little straggly. He wears a country-style shirt with big American Indian chief head silhouettes on its sides on one of his days in Houston. (There’s a Beto For Texas shirt underneath it.)

Hollywood did not get this biopic of Blaze Foley, a country blues singer who had only one album and one single to his name when he was murdered at age 39, made. Hawke and a lot of determination did.

“It’s a struggle for anybody to get anything made,” Hawke says. “I’m always astounded. If you want to do anything that didn’t just make people money… The thing that is most easy to get financed is an imitation of something that just made a lot of money.

“If that’s not what you’re doing — if you want to make a music film about a guy nobody’s heard of, that’s going to star somebody who hasn’t acted — it’s going to be challenging to get financed.

“But it’s challenging for Steve Soderbergh to get the movies he wants made. One of the biggest surprises to being in the room with people like that… Richard Linklater struggles constantly to get movies made. Because he’s always trying to do something different.

“If he would make Boyhood 2, yeah they would finance that. But he doesn’t want to do that.”

Hawke throws his arms up and shrugs. What’s an artist to do, but keep fighting.

Ethan Hawke, the Director

Hawke has little interest in the sequel parade. Or any kind of safety net, apparently.

He tabbed Ben Dickey, an obscure musician in his own right who’d never acted before, to be Foley. It helps that Dickey is the boyfriend of Hawke’s wife’s best friend and that the two have a genuine friendship to build trust off of. It still represents a huge risk, one that sending Dickey to Vincent D’onofrio — the actor turned acting coach who is Hawke’s favorite teacher — could not completely negate.

But there is Dickey winning the Special Jury Award for Achievement in Acting at the Sundance Film Festival. And there is Dickey eloquently talking about the man behind the legend of Blaze Foley and playing Foley’s songs beautifully.

“He was different than I expected,” Dickey says of Hawke as a director. “I trusted he’d know what he was doing. He’s a great leader. He sells everybody on adventure and exploration. We are doing this. It wasn’t like I’m doing this and let’s make it happen. It’s ‘This is what we’re doing today.’ And for the actors, he invites you into his vision.”

Like the real Blaze Foley, Ben Dickey is a big man with an easy charm. When I ask if he’s getting used to the press tour promoting a movie takes, he just laughs.

“With music and the band I was in, we’d always like two or three of these (interviews) and then the record would fail,” Dickey says.

Sitting at the small table, inches from his buddy, Hawke laughs at this too. The 47-year-old Hawke who acted in his first movie at age 14 (in Explorers alongside River Phoenix) knows what Dickey doesn’t. That most movies are set up to fail, too.

“I had no doubt that we could do it together if we had enough time and money,” Hawke says. “I had doubts we would be able to have the time and money. The trouble with Indie movies is that — I always try to tell young actors this — they’re not designed to help you. Young actors always think they’re going to come on set and someone’s going to help them act.

“They’re not. They’re thinking about, they worked hard t0o get this location. They worked hard to get these lights. They want to get this shot and get to the next one before they lose it. They’re not there to teach you how to act.”

The Houston Man

Sitting in Rockefeller’s — a bar that looks completely different in the heart of the day, with sunlight streaming through the windows — doing interviews for a movie that many didn’t think he could get made, Hawke cannot help but turn a little reflective. He’s in Houston, in Texas, opening a movie, which he equates to paying “your respects before you go sell it.”

Hawke is a huge fan of the stage, but this city is more than that to a guy who spent his early childhood in Austin.

“The Menil gallery is a museum that if it’s not free, it’s pretty cheap,” he says. “And there’s this amazing private collection. It’s phenomenal. And you tell people who live here a long time and they don’t even know it. And they’ve got just staggering amounts of art there. But if I had days here, the first thing I’d probably really want to do is go to an Astros game.

“I don’t know why. I like that I did it as a kid.”

Hawke shrugs with a real smile — not a movie star I’m selling you smile. A guy helping with the publicity of the film tries to hurry him along. There’s another reporter waiting in Rockefeller’s modest green room to interview him.

But Ethan Hawke doesn’t move. He’s going to sit and talk about Houston and Texas for at least a few moments more.

_md.jpeg)