From the Archives: Gay Dallas — A Look at the Past, Present, and Future of LGBTQ Culture in the City

A Journey Into a Brighter Future

BY Billy Fong // 06.29.20The 1972 march that over a decade later would be known as the Dallas Gay Pride Parade. (courtesy of UNT Libraries Special Collections)

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in 2019 in honor of the 50th anniversary of the pivotal Stonewall Riots.

During the wee hours of June 28, 1969, a riot broke out during a police raid at New York City’s Stonewall Inn — a gay bar in Greenwich Village. Those in the surrounding neighborhood erupted in response. Rioters threw bottles and rushed police barricades. Drag queens kicked their heels in the air like the Rockettes and sang: “We are the Stonewall girls. We wear our hair in curls … We wear our dungarees above our nelly knees …”

The riots were a rallying call. And change was in the air. Fifty years later, our zeitgeist begs a reexamination of gay culture — and not just in the United States, but also in our own city of Dallas.

In the five decades following the riot that sparked the gay community to stand up for equal rights, much has shifted. In Dallas, a city smack in the center of what many would call the conservative South, gay culture thrives. Our city has been credited as one of the most gay-friendly in the country, alongside New York, San Francisco, and others on both coasts.

Yet few know the history of its LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) community and culture. Some might know that Cedar Springs is the epicenter of the gay community, while others may recall Dallas appointing its first openly lesbian sheriff, Lupe Valdez, in 2005. But the history runs deeper — from pre-Stonewall-era gay bars that existed off the radar to today’s megawatt gay-pride parade.

From the Shadows

During the early 1900s, Dallas’ LGBTQ community existed in the shadows. Scarce details are known about the city’s gay history prior to World War II, says David D. Doyle Jr., a history professor at Southern Methodist University, who teaches a class on the backstory of the local LGBTQ community and is writing a book on the subject.

“Most records are vague, and few exist that explicitly describe so-called sex crimes, harassment, or homophobia,” says Doyle. “Same-sex relationships were often framed as friendships so are sometimes hard for us to understand from our present time.”

The true seismic shift began during the World War II, Doyle notes.

“When troops were sent to Europe to fight, American soldiers witnessed an air of sexual freedom in the larger cities than what existed in the US,” he says. “Many European communities existed at the time in large cities — London, Paris, and Berlin, for example — where gays were able to be themselves in certain establishments without fear of persecution, even if official recognition was still lacking.”

It’s not far from the world portrayed in the 1972 Bob Fosse-directed film Cabaret, which was a rather accurate snapshot of Berlin’s sophisticated gay subculture that existed from 1918 to 1933.

Cut to a post-war America. Former soldiers, particularly those who were questioning their sexuality, traded small towns for big cities, where there was a better chance of meeting other like-minded people. Here, they found bars and lounges that catered to a largely closeted gay community. But up until the 1970s frequenting such establishments came with the threat of regular police raids — and patrons of these bars and lounges were sometimes arrested and brought to jail, where most pled guilty for the crime of public lewdness to avoid attention.

As with other criminal reports, newspapers including The Dallas Morning News and the now-defunct Dallas Times Herald would publish the names of those arrested as part of the publications’ crime sections. The ramifications of being outed as gay often ranged from job loss to being ostracized or disowned by one’s family.

The speakeasy-style establishments of the 1950s and ’60s were a far cry from the gayborhood we now have on Cedar Springs Road. Theater Row in downtown Dallas was the well-known cruising spot — a place for gay men to meet other gay men. To show that one was looking for a sexual encounter, men would pose in a specific posture: leaning against a building with one leg raised, a foot planted against the wall, both thumbs hooked into his trousers.

Bars from the Mad Men era were scattered throughout downtown. One of Dallas’ earliest gay bars — and for a while the oldest and longest-running gay bar in the country — was Le Boeuf Sur Le Toit (translation: Beef on the Roof), which was later renamed Villa Fontana. The now-shuttered Lasso Bar and The Zoo were in close proximity to Neiman Marcus. And Elvira’s had a red-and-blue light inside that was used as a warning signal. If a patron came in who the staff feared might be an undercover police officer, the light flashed red. When the light shone blue, it meant the bar was safe, and guests could confidently continue any clandestine activities.

A Legendary Saloon

The city’s gay-bar culture has come a long way since then. And, it would be hard to paint a picture of Dallas’ gay history without a brief primer of the legendary Round-Up Saloon, which many describe as Brokeback Mountain live. Originally opened in 1980 by Tom Sweeney (with a name that only lasted one year, Magnolia TP; the TP stood for Thunder Pussy), the Round-Up has been owned by Gary Miller and Alan Pierce since 1998. Today, this bar has transcended sexual orientation and social stigma.

“I was cold-called one day in 2008 by a young woman who wanted to come in and sing a few songs,” Miller says. “We generally didn’t let just anyone off the street come in to perform, but decided to take a chance on her.” That soon-to-be-massive superstar was Lady Gaga.

Whenever chic foreigners come to Dallas, they want to experience the Round-Up, too. Dozens of über-glamorous fashion-world notables who came to town in 2013 for the Chanel Métiers d’Art fashion show made their way to Cedar Springs to soak in the gay-cowboy ambiance.

“Staff actually panicked when guest after guest made their way to the dance floor and began piling their furs on the bar,” says Pierce. Dallasite Fred Holston of the Kim Dawson Agency remembers another wild night: “I danced one evening at the Round-Up with Jean Paul Gaultier when he was here for his exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art.”

Even the song “Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other,” originally written by Ned Sublette, entered the mainstream by way of the Round-Up when Willie Nelson covered it in 2006 and filmed the music video at the fabled saloon. The song itself, which throws the heterosexual, hyper-masculine construct of a cowboy to the wind, is another testament to how far the LGBTQ community has come.

Of course, it doesn’t end at the Round-Up: Today, Dallas has LGBTQ lounges to fit almost every niche audience — and a Saturday night on Cedar Springs is often a mix of people of all sexual orientations. The Dallas Eagle has long been a go-to for the leather community. Here, one might find men in chaps or a harness perusing the bar’s retail area in search of a new leather biker cap or police-inspired sunglasses. And The Hidden Door, a longtime establishment, has famously welcomed a wide section of socioeconomic groups since opening 40 years ago.

The world of drag has also found mass appeal, largely due to the wild popularity of reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race. There’s something compelling about these over-the-top female impersonators that have long struck a chord in pop culture. In New York City during the late 1970s and early ’80s, Harlem was famous for its fierce drag competitions, which were known as the “Balls.” Today, drag shows can be found all over town in the Rose Room Theatre and Lounge, Alexandre’s Bar, Woody’s, and Liquid Zoo.

Local and out-of-town drag performers Endora, Janet-Fierce Andrews, and Jasmine Masters keep crowds wrapped around their cocktail-ring-adorned fingers with their flamboyant performances. One North Texas performer has found himself on the drag map with the debut of the Netflix series Dancing Queen, which chronicles the life of Justin Dwayne Lee Johnson, also known by his drag name, Alyssa Edwards

Johnson owns a popular studio, Beyond Belief Dance, in Mesquite. The Netflix series chronicles Johnson as he teaches children in the world of competitive dance.

Betty Neal, a 62-year-old black lesbian activist, credits black drag performers for “uniting the black and white gay communities.” During the 1980s, popular Dallas-based black entertainers such as Lady Shawn, Latina McEntire, Amazing Grace, and Racine Scott were often booked at nightclubs and bars that were thought to primarily cater to a white clientele.

Dallas’ Push for Equal Rights

In Dallas, the rallying cry for equal rights is said to have been sparked not by Stonewall, but by two other events: Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign of the late 1970s, during which the former orange-juice spokeswoman vehemently rallied against gay rights, claiming it went against her right to teach her children biblical morality, and the AIDS epidemic of the early 1980s.

Until the early 2000s, anti-sodomy laws, which criminalized sexual acts between same-sex individuals, were often used to prosecute homosexuals. One of the first landmark cases that attempted to repeal the law was Baker v. Wade. After coming out as a gay man on a television interview in 1977, Don Baker was fired from his teaching position with the Dallas Independent School District on the grounds of his being gay

Two years later, Baker filed suit to have the sodomy law deemed unconstitutional. The suit was funded by the Texas Human Rights Foundation — Texas’ first statewide LGBTQ organization — and Baker and his team won. But in 1986, a successful appeal was filed, and the anti-sodomy law was reinstated — remaining intact until 2003, when the Supreme Court struck down all such laws as unconstitutional as part of the Lawrence v. Texas ruling. (The Lawrence v. Texas case dealt with a same-sex couple in Houston that was arrested in 1998 for violating anti-sodomy laws.)

In the 1980s, the flames of homophobia were fanned by the onset of the AIDS epidemic. Little scientific knowledge was known about the cause and treatment of the disease, and it was thus sometimes referred to by ultra-conservative religious and political groups as God’s punishment for gay lifestyles. In response to the health crisis, grassroots organizations popped up, providing medical care, information, and emotional support.

One pioneer was Dallasite Ron Woodroof, whose story was first told by reporter Bill Minutaglio in The Dallas Morning News’ Sunday magazine in 1992. Woodroof, an AIDS patient, created the so-called Dallas Buyers Club as a front to provide AIDS patients access to effective drugs that were not approved by the FDA. In 2013, actor Matthew McConaughey would play the late Woodroof in the acclaimed film Dallas Buyers Club, for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Longtime Dallas activist Rodd Gray — and his drag persona, Patti Le Plae Safe — recalls the AIDS era in an oral history video filmed by The Dallas Way, an organization documenting the history of Dallas’ gay community, by way of video and audio recordings (dubbed “Outrageous Oral”), as well as written stories, all told by local LGBTQ individuals.

“I hated to go home and turn on my answering machine and hear someone needed diapers. Someone needed a ride to the doctor’s office,” she says in the video clip. “And then there would be someone died … someone died… someone died. There were weeks when I didn’t turn it on at all.”

For Gray and other members of the gay community, the AIDS epidemic was riddled with trauma — from the medical emergencies to the social stigma that came with the disease. It was inconceivable at the time that Princess Diana would shake hands with an AIDS patient — or that Elizabeth Taylor would embrace Rock Hudson, who was dying of AIDS.

In the wake of anti-sodomy laws, discrimination, and the AIDS crisis, Robert Emery, a 40-year community leader and a co-founder of The Dallas Way, notes that Dallas dealt with LGBTQ discrimination differently than the Northeast and the West Coast.

“They knew it was best to work within the system and honor the classic establishment,” Emery says. “Yes, we had activist protesters who were outlining bodies in chalk and marching in the streets, but some Dallas LGBTQ leaders took a decidedly different approach by putting on corporate attire and meeting non-gay community partners.”

In Dallas, gay men and lesbian women worked side-by-side to effect societal and legal change, a collaboration that was not always the case in other cities. In 1974, Dallas community leader and activist Lory Masters founded a motorcycle club, the Flying W’s, which became the first LGBTQ organization to receive official 501(c)(3), non-exempt tax status in the state of Texas. This made it one of the first gay-focused nonprofits to be recognized as legitimate.

Prejudice within the gay community itself has been a longtime phenomenon. White gay men have historically enjoyed more privileges when compared to black gays, lesbians, or trans people. When going out on the town, Betty Neal remembers often being confronted with the demand “I’ll need to see two IDs from you” from bouncers at local gay bars.

This barrier to entry was often posed to black patrons but not to white ones up until the early 1990s, she says. And so, the black community opened its own gay bars.

“Only we knew about them,” Neal says. “Lady Love was a drag bar, strip club. It was poppin’. Some of the original black Dallas drag queens got their start at Lady Love.”

The LGBTQ black community, not always feeling accepted in the Gay Pride Weekend, in turn, created its own celebration, which is known today as Dallas Southern Pride and Dallas Black Pride. Started in 1997, it coincided with the State Fair Classic, a rivalry football game between Historic Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) Grambling State University and Prairie View A&M. Last year’s pride event drew more than 15,000 people.

Perhaps one of the last groups within the LGBTQ community to gain public acceptance is the trans population. Only recently have trans people been humanized in mainstream media by way of television shows such as Transparent and the public transition of Olympian Bruce Jenner, who became Caitlin Jenner after undergoing sex reassignment surgery in 2017. Her journey was documented before millions of viewers via reality television shows I Am Cait and Keeping Up With the Kardashians.

While Dallas’ LGBTQ community still faces challenges, it also has many bragging rights. The city had its first gay parade in 1972, eventually coming together again and forming the Dallas Gay Pride Parade in 1982. Now named the Alan Ross Texas Freedom Parade, the event draws tens of thousands of locals and tourists. The Cathedral of Hope, designed by architect Philip Johnson, serves the local LGBTQ community and is said to be the largest church of its kind in both physical size and member congregation of more than 4,500 people.

Numerous fundraisers supporting issues that impact the gay community have loyal followings in Dallas. There is the incredibly chic TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art, an annual contemporary art auction benefiting the Dallas Museum of Art and amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research. TWO x TWO, always a sell-out, is the second-largest fundraiser for amfAR in the world. The Dallas chapter of DIFFA (Design Industry Foundation Fighting AIDS) is notably strong, with nearly 2,000 attending its annual gala, which raises funds to provide education and direct care service grants for men, women, and children affected by HIV/AIDS. And since its inception in 1982, Black Tie Dinner has been the largest fundraising dinner for the LGBTQ community in the nation and to date has distributed more than $23 million to local and national LGBTQ organizations.

Few more pivotal laws symbolize progress in LGBTQ rights than when, in 2015, the Supreme Court struck down all state bans on same-sex marriage. Dallasites George Harris and the late Jack Evans — often described as the elder statesmen of the Dallas gay community — had been a couple for 50 years, when the momentous Supreme Court ruling was announced. They were the first in line to get married that day — and they hold the title of being the first same-sex couple to be legally married in Dallas.

When asked to measure how far society has come in terms of equal human rights, answers often vary by generation and age. Baby Boomers might find today’s world a radically new environment, given the vast scope of societal and legal changes they have observed since the post-war era. Generation Xers, on the other hand, may yield a sense of apprehension when it comes to measuring the progress of LGBTQ rights — perhaps the result of having come of age during the fear-mongering years of the AIDS epidemic. Millennials tend to fall on the polar opposite end of the spectrum, viewing sexuality in even more fluid terms. And only time will tell what Generation Z will bring to the table.

A fitting statement of our current times — and the millennial impact on the future conversation surrounding sexuality and gender — perhaps, comes from 27-year-old Fred Holston.

“Within the last couple of years, I’ve started to allow myself to let go of gender altogether, and everything started making sense,” says Holston. “The reason I felt out of place and had a hard time connecting with the gay male experience was because I wasn’t a gay man, and in fact, I wasn’t any kind of man… I am not a man. I am not a woman. I am Fred.”

And with that, the future is blown wide open.

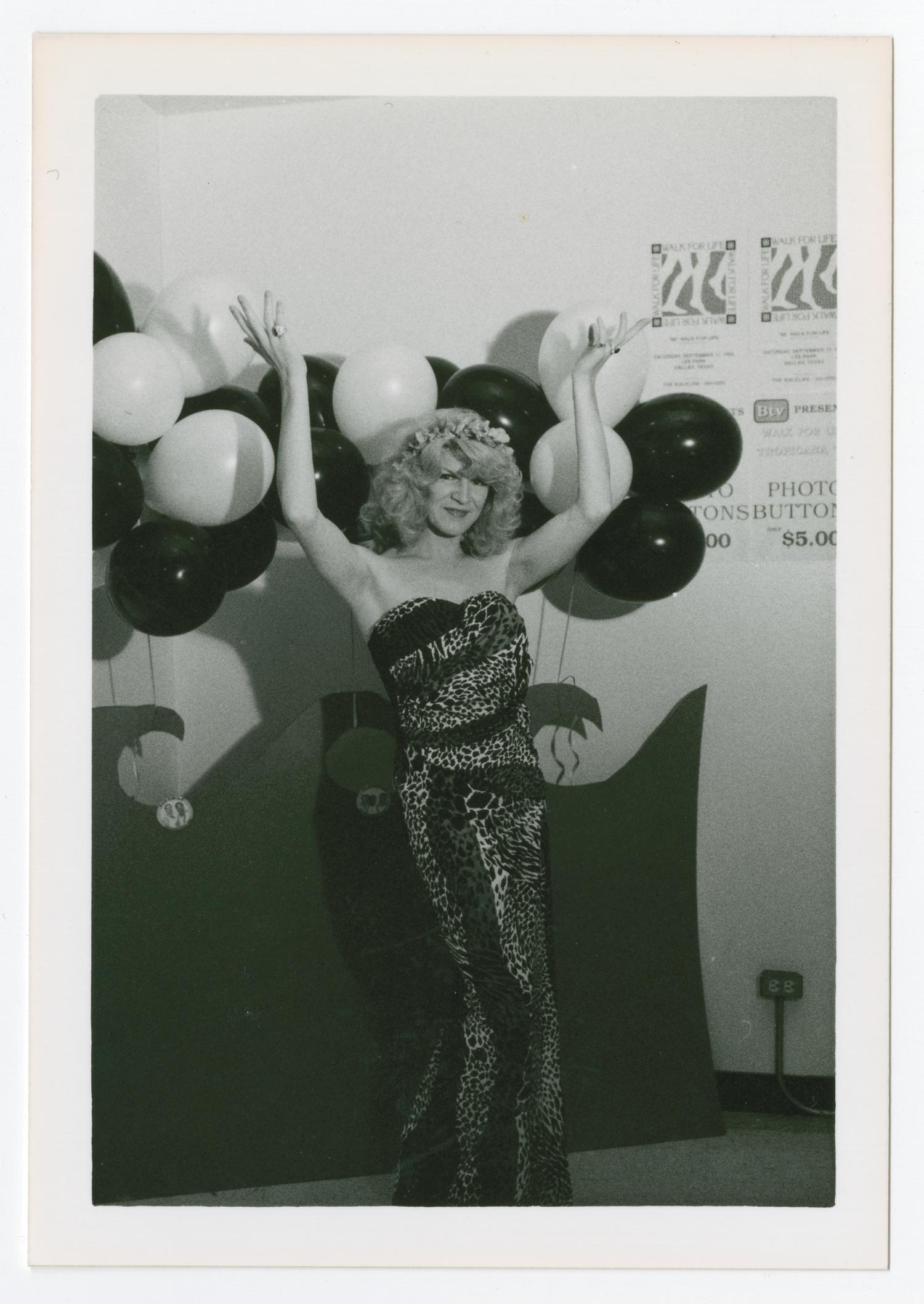

![Phil Johnson at a Pride Parade, photograph, [1993..], courtesy of UNT Libraries Special Collections.](/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/metadc277356_m_UNTA_AR0756-109_01.med_res-698x1024.jpg)

_md.jpg)