The Real History of Houston’s Most Iconic Restaurant and How Cafe Annie and Robert Del Grande are Being Reborn

What Started as a French Bistro Has Evolved Into a Tale Full of Plot Twists, Real Estate Realities, a Pioneering Chef and Second Chances

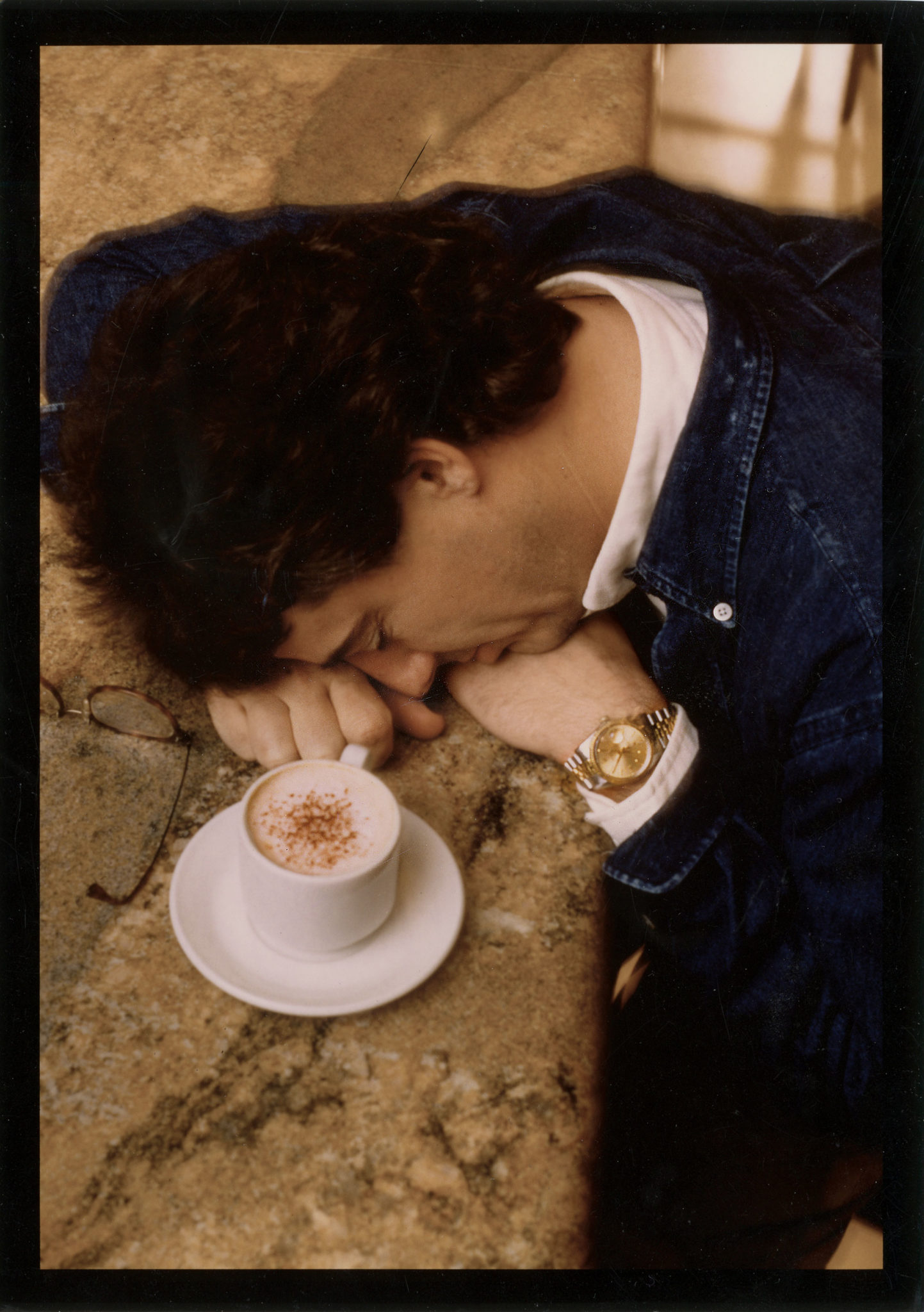

BY Laurann Claridge // 10.13.19Robert Del Grande in the kitchen of the original Cafe Annie on Westheimer, 1984

In 1981, Robert Del Grande arrived in Houston to visit his girlfriend, and a year later, he became one of four co-owners of Cafe Annie, the French bistro located in a modest strip center on Westheimer Road. Four iterations later — with name changes along the way — Del Grande is striking out of the original group and partnering with restaurateur Benjamin Berg to launch a rebrand, this time named The Annie Café & Bar.

It began when the scholarly Del Grande, a 26-year-old Ph.D. grad student studying biochemistry at the University of California, Riverside, met his future wife, the outgoing, fun-loving coed Mimi Kinsman, who was also a California native. Fast forward to Mimi’s college graduation, when she moved to Houston to work with her sister, newlywed Candice (or Candy, as she’s known) and her husband, Lonnie Schiller, a Texan who ran an advertising and marketing agency.

Candy and Lonnie had traveled to Europe during the late ’70s. Like so many during that era, they came home dreaming of opening a French bistro as charming as the ones where they had dined in Paris. And that’s exactly what they did.

The intimate bistro was dubbed Cafe Annie. Off for summer break, Del Grande came to Houston to spend time with Mimi. He was enthralled with cooking.

“I wanted to help out at the restaurant,” he says. “I was cooking at home from cookbooks but was curious what it was really like in a restaurant kitchen… My only hospitality experience was scooping ice cream at a Baskin-Robbins when I was 17.”

He read Jacques Pepin’s ground-breaking La Technique cover to cover and voraciously pored over Michelin-starred chefs’ cookbooks, from the Troisgros brothers to Michel Guérard, stars of the culinary scene who at the time were popularizing lighter, French-technique-driven nouvelle cuisine across the globe.

“In school, you spent half the day reading in the library, but to my surprise, the French chefs at Cafe Annie weren’t keeping up with what the chefs were doing in France,” he says.

After a short stay, Del Grande headed back to California to complete his Ph.D. Nine months later, when faced with the conundrum of what to do with the rest of his life, he contemplated moving to Switzerland or even Chicago to work on a postdoctoral degree, but his fiancée wanted to stay in Houston, so he returned to work behind the range at Cafe Annie.

“I was the cook with the book who encouraged them to push this and that,” he says. “I was used to working day and night in the lab anyway, but not everyone was. They relished a night off, but I wanted to be there.

“I think the chef really wasn’t cut out for the job, He loved windsurfing and other things more and eventually left. When he did, there was talk of what we should do. Should we hire another chef? And I said, ‘I have a lot to learn, but I can do this. I’ll make this happen.’ It was one of those sheer moments of opportunity.”

But jumping from the intricate, subtly flavored fare of France to what would become his trademark — the bold flavors of Texas and the Southwest — was a slow evolution.

“We all wanted to be French in the late ’70s and early ’80s,” he says. “The more difficult it was, the better, and the French were very good at making things difficult. If you wanted to be the best, you had to be French.

“Then three things converged. One was the principle of nouvelle cuisine that mandated you had to use the best, freshest ingredients. It was an early local thing. Next, there is no way we could be better than the French — according to the French. And, third, these were not dishes you made at home. The foods we really liked, that we ate in the back of the kitchen, were the origins of Southwest cuisine: the local, fresh stuff combined with some Mexican influences, all of which was the complete opposite of French cooking.”

Back then, in the early ’80s, Houston colleagues such as Amy Ferguson (Charlie’s 517) were meandering down the same path as Del Grande — ditto in Dallas, with chefs Stephan Pyles (Routh Street Cafe), Dean Fearing (The Mansion on Turtle Creek), and Avner Samuel (Loews Anatole Hotel). Circa 1984, cookbook writer and consultant Anne Lindsay Greer suggested several of them come together to put on a potluck dinner in Dallas and show the world that Texas has its own unique take on regional cooking. She convinced them that by working together, they could attract more attention than they could ever garner alone.

In a 2014 retrospective story, Texas Monthly food editor Patricia Sharpe wrote of the movement: “How can you pinpoint the beginning of something as sweeping as a culinary movement? You can’t … To appreciate the radical nature of that act, it helps to remember how stratified restaurants were then: there was fine dining, defined by French food and ‘continental’ cuisine, and there was everyday dining, and the two seldom overlapped.

“Yet at their very first dinner meeting, the Texans recognized one another as kindred spirits who believed that our state’s humble foods — enchiladas and salsas, smoked meats and fried chicken, okra pickles and chowchow, buttermilk biscuits and peach pies — were not just homey favorites. Treated with imagination and refinement, they could equal anything the Old World had to offer.”

Attract attention they did. Throughout the mid-’80s through the ’90s, the food world exhaustively covered the trend baptized Southwest cuisine. Every major publication, from Bon Appétit to Gourmet, as well as industry insiders such as Restaurant Hospitality, not only spread the word but anointed Del Grande, one of the movement’s founding chefs, with accolades ranging from the coveted James Beard Award to Best Restaurant honors in a 1999 issue of Food & Wine. Del Grande, along with now-wife Mimi, who ran the front of the house, and partners/in-laws Candy and Lonnie Schiller were running what was arguably the most famous restaurant in the city of Houston.

In 1989, nine years after Cafe Annie’s founding, the foursome decided to move from their 3,500-square-foot Westheimer address to the highly visible Galleria area. The new Post Oak location, near San Felipe, was nearly three times larger. With the help of partner/interior designer Candy Schiller, they upgraded everything from the stone floors to the rich mahogany book-matched veneer that cloaked the walls of the soaring, dramatic space. Cafe Annie was the reservation to get.

It was the see-and-be-seen-place where diners’ names were dropped in the gossip columns of the day and milestones happened, from signing a big oil deal to celebrating a wedding anniversary.

Boldfaced hometown names, from George H.W. Bush to astronaut Alan Shepard and ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, made the place their own. Even the most famous chef in France, Paul Bocuse, made a pilgrimage through Cafe Annie’s hallowed doors. Thankful that Del Grande served him anything but French fare, he delighted in the regional cuisine that had been elevated from humble to approachable haute.

Then there were the fabled New Year’s Eve parties, packed with women dancing on the bar. “In the ’90s, the economy was blowing along,” Del Grande says. “New Year’s Eve was an odd thing. It was like a badge of honor that you could survive it. We would do all this elaborate stuff. There were two seatings — the quiet 6 pm and, later, the wild second seating.”

As they rolled toward the year 2000, each party got crazier.

“I don’t remember how it started, but then there was a gong, Silly String, and you’d wake up the next day with glitter on your pillow,” says Del Grande, who would sit back and watch Mimi and company jump onto the bar, turn up the music, and dance like it was 1999, to quote the Prince song. And it was. After the eve of 1998, in the wake of Y2K, they closed out the last year of the millennium with no fanfare whatsoever.

Whether that moment was the harbinger of change, we’ll never know, but change was indeed afoot, with cell phones beginning to proliferate.

“I made this prediction in 1999,” Del Grande recalls. “I said, ‘Cell phones will change everything. If you change the way you communicate, you will change the way you socialize, and we’ll all change.’”

When they moved to the first Post Oak location, the restaurant was much bigger and more dramatic, but “the difference was that everything was concentrated in the dining room,” he says. “The bar was simply a place you waited for a table. But there was a certain group who would eat at the bar. It was like ‘If there is all this hoopla in the dining room, I’ll just sit in the bar.’

Then a light went off in my head. I thought: ‘What’s the difference between bar food and the food in the dining room? You can eat bar food with your fingers!’ We couldn’t put a burger on the main menu, but we could serve it at the bar. That was the difference.”

While people were still wearing coats and ties in the dining room, the bar was surreptitiously gaining a certain cachet.

In the years leading up to 2009, things changed in a bigger way: Their landlord had other plans for the space they occupied, near the intersection of San Felipe and Post Oak Boulevard. Over the years, commercial real estate developer Ed Wulfe had been acquiring land around the Post Oak area and envisioned something much bigger, much grander — a development he’d call BLVD Place. His idea was to move the restaurant a few yards up the street to occupy an expansive two-story space.

“I think the whole plan initially was that Cafe Annie was going to be the endcap of the new development, where there would be a hotel, shopping, etc. It was proposed as the place you needed to be, but instead, it turned into ‘What’s going on there? What’s with all that construction?’” Del Grande recalls. “I thought, ‘I don’t want to move. I want to wait until the development is more complete,’ because if they are going to build a hotel we could be a part of it, much the way Fearing’s is within The Ritz-Carlton Dallas.”

But the hotel never happened.

“The problem with the restaurant was that when we designed it, everything was in such a rush,” Del Grande says. “Before you knew it, they’re telling you the elevator’s in, and then you’re trying to figure out where the front door should be. We never had a chance to really think it all through.”

When the foursome had initially made the move from Westheimer to their first Post Oak space, the layout was almost identical, save for a quick flip of the blueprints.

“When we had to move again to the new Post Oak location, nothing was the same,” Del Grande says. “There was a lower ceiling, the space faced another direction, and there was no way we could take the former design and place it in the new one, nothing fit. Not to mention the problematic two-story, upstairs/downstairs situation with the kitchen and dining level on the top floor and the entry and restrooms on the first, which had customers complaining from the start.

“While we tried to soften things up with a different design the question eventually became: How can you call it the same name if it’s not going to even resemble the other in the least?”

Name Games

Thus, with the move, the iconic Cafe Annie name went by the wayside, replaced with RDG — the chef’s initials. Yet Bar Annie’s name stayed the same. The new place was now labeled RDG + Bar Annie. To confuse matters further, Del Grande recalls that diners would telephone the new location and ask, “Is this still Cafe Annie?”

Others would drive past its former stead, see a construction site, and wonder where it had gone, never realizing it was only a block away. And then there were the out-of-towners who had no idea what was going on.

But that was the least of their problems. “I thought we had a bad break with Mo’s restaurant across the street, too,” he says. “That rowdy group [complete with hookers] would cross the street, cocktails in hand, and jam up our bar. It was nuts. We had to have someone downstairs collecting their drinks. The restaurant was not set up for that, we never anticipated it… A lot of people got the wrong message in the beginning.”

And just about this time, younger diners were heading everywhere else, as a veritable boom of restaurants was hitting Houston. One could hardly begin a casual conversation without the phrase “Have you been to [name of latest restaurant] yet?” spilling from one’s lips.

A city that had always staunchly supported those who started their careers in town began to embrace outsiders, making competition for dining dollars fierce. Cafe Annie began losing pivotal, long-tenured front- and back-of-the-house employees, but Del Grande and company took each departure in stride.

As the 35th anniversary approached in June 2016, they contemplated ways to mark it. Nixing the idea of a big party, they decided instead to bring a few Cafe Annie signature menu items back to RDG. Then someone on the team (no one is sure just who) thought it would be a brilliant idea to change the name back to Cafe Annie, typography and all, which led to nothing but more confusion.

In 2017, in an outward sign of business slowing significantly, the Schiller Del Grande Restaurant Group (as they are collectively known) decided to refashion what was essentially a dead first-floor entry space into a small retro eatery, serving wood-grilled steaks and oysters. While the food was fabulous and up to the standards they’d set decades prior, the short-lived concept was far from the talk of the town.

A Cafe Annie Restart

Now 64 years old, Robert Del Grande is stepping up for his grand redux and stepping out on the stage solo. Mimi has retired, and the Schillers are busy consulting on hotel and restaurant projects elsewhere, although the foursome still retain operations at the downtown eatery The Grove at Discovery Green.

In a deal brokered by the site’s late developer Ed Wulfe, Del Grande has partnered with restaurateur Benjamin Berg and renewed the lease for another decade. Together they’re working to completely revamp what once was — concept, design and menu — to bring something exciting and altogether new to the fore.

Berg, a native New Yorker and alum of the Cornell School of Hotel Administration, moved from Manhattan to Houston several years ago with his wife and three young children in search of a better quality of life. After a management stint at the Houston location of Smith & Wollensky, Berg has gone on to open his own popular steak place, B&B Butchers & Restaurant, in Houston, then Fort Worth.

Shortly after, two Houston locations of his more casual concept, B.B. Lemon, premiered. Almost simultaneously, he acquired the old Carmelo’s restaurant in west Houston, now rechristened B.B. Italia and B.B. Pizza. All in a span of four short years.

Berg admits to combing the massive archives of the New York Public Library’s old restaurant menu collection for fun.

“When I moved to Houston,” he says, “I learned about the history of the restaurants here. Everyone told me about Café Annie and Tony’s and Maxim’s.”

While aware of Del Grande’s legacy and influence, Berg initially hesitated when Wulfe approached him in April 2018 about getting involved.

“It was just bad timing,” he says. “I had just opened B&B Butcher’s in Fort Worth and had other stuff going on with the Italian restaurant, and I thought, ‘I don’t want to do another restaurant right now.’ ”

But a fortuitous meeting at Galatoire’s in New Orleans several months later brought Berg and Del Grande together, where both were dining separately. Berg says, “For me, this is a real people business, and I didn’t know Robert, but we started talking. When we got back to Houston, we got together and talked again — that’s what got me in. He’s a great guy. I wanted to work with him.

“To be able to work with some of the real pioneers of Houston food and be a part of a name that everybody knows is really exciting. It puts a ton of pressure on me … You will always have people who will say, ‘I liked things this way,’ but things have to change over time. I’m a big believer in that.”

What’s in store for diners now that the3 doors of The Annie Cafe & Bar are reopened?

“I think we’re going to blow people away with the interiors and the new look, creating a new atmosphere for the next 20 years of Annie,” says Berg. Initially what made Berg step away from the deal was the challenging second-floor space. But with the help of architect Issac Preminger, he says, they’ve figured that out.

One of the biggest customer requests — adding bathrooms to the second floor — was an easy fix. In addition, Berg says, “We’ve moved the stairs over, created a real entrance and an energy to the room.” The bright, clean space — with an oval two-sided bar that will seat up to 50, white-painted brick, hardwood floors, and palm trees — won’t resemble the old in the least.

As for the fare, you’ll find a few classics on the tightly edited menu of Del Grande’s much-imitated creations, from coffee-crusted filet to the famous crab tostadas. To be sure, change is afoot.

“The restaurant became a celebration place, and I don’t think people thought it was approachable anymore,” Berg says. “The prices got up there, too… My idea is to have fun, get Robert excited again.

“If someone comes in and wants something from the old menu, that’s the hospitality part. You want it, we’ll make it.

“The new Annie Cafe & Bar will respect the fundamentals: Buy great ingredients then don’t ruin them. I don’t think food has to be crazy and wild. It has to be really good. I want to keep the essence of what made Annie great, improve on it, bring a new crowd to it, and show that this thing has legs. Oh, and to not screw up what Robert’s done for 38 years.”

_md.jpg)