A Legendary Texas Socialite Who Lived to 100 Leaves an Incredible Story Behind: The Unbelievable True Tales of Betty Blake

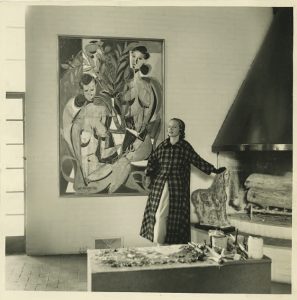

BY Rebecca Sherman // 10.14.16Betty Blake with Claude Venard painting in 1955 at Donald Vogel's residence

To put it in her own words, Betty Blake “didn’t give a hoot” what anybody thought of her. She lived on her own terms, rollicking through a century of highs and lows with grace and drollery. Her mother survived the sinking of the Titanic, yet Betty’s own challenges were no less epic: She weathered hurricanes, five husbands, and the death of her first son — all the while, her dry sense of humor doggedly intact.

“I never saw her depressed,” says close friend and interior designer Joseph Minton, who knew her for almost 50 years. “She was always laughing.” Betty’s blue-green eyes danced when she would recall her glamorous schooling in Paris as a child, or her opulent coming-out ball in Newport, Rhode Island, where her family summered. Her rose-petal skin made her look decades younger than her years, and her thoroughbred Philadelphia accent — which reminded her acquaintances of Katharine Hepburn — eventually mellowed with a slight drawl.

To her friends, she was Boop, a nickname she picked up in Newport in the 1930s. It was in reference to the diminutive cartoon character Betty Boop, says 97-year-old Oatsie Charles, a Newport socialite and one of Betty’s longtime friends.

Decades ahead of her time, Betty introduced modern art to Texas in the 1950s with the Betty McLean Gallery — her name then. “She was a great source of support for artists and the whole Texas arts community,” says Marla Price, director of the Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth, where Betty sat on the acquisitions committee for 50 years.

Her taste for avant-garde art was a half-century before its time — Harry Parker, former director of the Dallas Museum of Art, once declared that Betty had “the best eye for contemporary art in America.” She is credited with shepherding the careers of local greats such as Vernon Fisher and David Bates, and Betty’s cocktail parties in the ’60s and ’70s were legendary: Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, di Suvero — they all came.

Vivacious with boundless energy, Betty trekked Nepal at age 88, drove her own car well into her 90s, and swam in the ocean regularly until last year. She read The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal daily, resorting to a magnifying glass when her eyesight began to fail. A devout Christian Scientist, she didn’t drink, smoke, or take medicine. Betty was wheelchair bound the last year of her life, but when she died unexpectedly on August 8 after complications from a fall at her Newport home, family and friends were devastated. Says Oatsie: “We thought she’d outlive us all.”

Born into great wealth and pedigree, Betty Brooke Blake grew up amid extraordinary privilege and splendor. Her family home, Almondbury, was located on the prestigious Main Line, a string of leisure-class communities extending west out of Philadelphia along the Pennsylvania Railroad. A bastion of old money, the Main Line was home to sprawling estates, cricket and hunt clubs, and the occasional eccentric family. Architect Horace Trumbauer, known for designing massive palaces for the era’s industrial magnates, built most of the houses there, including Almondbury.

“The area was very WASP-y, very aristocratic English,” says David Nelson Wren, whose book, Ardrossan: The Last Great Estate on the Philadelphia Main Line, comes out next year. “People on the Main Line still lived with the vestiges of the Gilded Age.” That meant ballrooms and a full staff of live-in servants, including lady’s maids, valets, butlers, chauffeurs, and private tutors.

The Titanic Survivors

Betty’s childhood home, a rambling, ivy-covered Tudor built in 1911, was set on 30 acres and likely one of Trumbauer’s more modest estates. By contrast, the Ardrossan estate next door was certainly one of the architect’s most spectacular achievements. The fabled 1,000-acre, 50-room Georgian fortress is best known as the inspiration for The Philadelphia Story, a play by Philip Barry that became a movie starring Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, and Jimmy Stewart. Hepburn’s madcap character, Tracy Lord, was based on social butterfly Hope Montgomery, whose family still lives in Ardrossan.

Although Hope was a few years older, she and Betty were friends. They’d both attended the Foxcroft School in Virginia, and their families often traveled together — and at one point, even went into business together.

Betty’s mother, Lucile Stewart Polk, was a Baltimore debutante of genteel lineage. A descendant of President James Polk, she was a great beauty. Lucile’s striking clothes — and antics — were often chronicled in newspapers. By one account, she startled Newport society one summer season, dressed head-to-toe in flaming red. Athletic, she was reported to be the first woman to play polo riding astride, and she was often seen driving her own six-horse carriage through the busy streets. Other ladies of the era spent time reading, sewing, and receiving guests; Lucile preferred to play the stock market.

After her marriage to coal-mining heir William Ernest Carter, the couple moved to Europe — their servants and William’s string of polo ponies in tow. It was on a return trip to the United States in 1912 that they booked first-class passage on the RMS Titanic. The boat, as we are all now privy, sank after hitting an iceberg. Lucile and her husband survived, along with Betty’s 11-year-old half-brother and 14-year-old half-sister. (Betty would be born four years later, when her mother divorced William and married banker and steel manufacturer, George Brooke Jr.)

After the disaster at sea, Lucile was hailed as a heroine for helping row lifeboat No. 4, packed with women and children, in the frigid waters to safety. Her husband didn’t fare as well in the court of public opinion, however. Lucile sued for divorce, citing “cruel and barbarous treatment.” Her sworn testimony, obtained by the press, revealed that William had left his family to fend for itself while the Titanic sank. British and U.S. government inquiries into the tragedy documented that her husband escaped in a collapsible lifeboat with Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, which built the Titanic, arriving to safety long before others.

Betty steadfastly refused to talk publicly about the Titanic for most of her life. “It happened before I was even born!” she’d exclaim in exasperation when asked. While she remained mostly mum, a wealth of documented information about the Titanic inextricably entwines her family to the disaster forever. When James Cameron’s film was released, it was peppered with Carter family details: The now-famous Renault automobile in the ship’s cargo, a gift from William to Lucile, became the setting for a tryst between Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet.

David Nelson Wren, who interviewed Betty a year before her death, says she credited John Astor with helping her 11-year-old half-brother, Billy Jr., escape by placing a woman’s hat on him. (Even though he was a child, some officers would only let women and girls aboard lifeboats, provided they were first-class passengers.) The real-life scenario, told to her by her mother, became inspiration for a similar scene in the movie.

“What Betty seemed to ponder, though, was where the hat came from,” says Wren. “She said she didn’t know if it was a maid’s hat, her mother’s, or even Madeleine Astor’s hat.” We may never know, but regardless, the tragedy that occurred four years before Betty’s birth would leave an indelible mark.

Keeping Up With the Rockefellers

A member of what Gore Vidal described as “America’s ruling class,” Betty’s family shared the power and advantages of many of their patrician compatriots — the Rockefellers, the Vanderbilts, and other captains of industry. Her life was one of boarding schools, summers in Vichy and Newport, debutante balls, and blue-blood associations. At Madame Chapon’s finishing school in Paris, where she spent two years, Betty knew Lady Fermoy, who later became Princess Diana’s grandmother. At 18, after making her debut in Paris, she returned stateside, coming out at Newport’s most-legendary Ocean Drive “cottage” — the 30,000-square-foot French neoclassical Miramar mansion, owned by Eleanor Elkins Widener. The irony couldn’t be missed: Eleanor and Betty’s mother were lifeboat companions on the Titanic.

Betty was fiercely independent and seemingly impervious to criticism — traits she cultivated early on, partly in response to her mother’s indifference. Lucile never visited her at school in Paris, Betty said, and she was less than charitable about her daughter’s looks. Karl Willers, executive director of the Newport Art Museum & Art Association, elicited a candid interview with Betty in 2006, for a catalog the museum published in conjunction with an exhibition of her private art collection: “My mother was very, very beautiful — she was a blonde — and she considered me to be very, very ugly. She always said, ‘Oh, you poor thing. You’ll never get a man with that nose spread out all over your face.’ ” But, Betty’s pluck and resolve steeled her against the odds.

“Luckily it didn’t affect me, not at all,” she said. “I sort of rolled with the punches … and didn’t give a hoot! I never considered myself to be a great beauty. That’s not all there is to life.”

Lucile died in 1934, the same year Betty made her debut. Set somewhat adrift, Betty shuttled between Almondbury — her father adored her, she said — and Palm Beach with her friends. Before the year’s end, she eloped to London with the East Coast’s most eligible bachelor, 19-year-old Tommy Phipps. Nancy Astor’s nephew, and son of the English architect Paul Phipps, Tommy was the son of American socialite Nora Langhorne, the youngest of the beautiful and much chronicled Langhorne sisters of Virginia. Yet, even when presented with Paul’s unimpeachable aristocratic lineage, Betty’s family disapproved. “He wasn’t from Philadelphia,” Betty would say.

Tommy was a writer and editor at Vanity Fair in New York. In London, the couple lived a devil-may-care, carousing life, with Betty — a teetotaler — often driving Tommy, Lord Astor, and all the Astor boys pub-hopping. F. Scott Fitzgerald and Fred Astaire were Tommy’s chums, and when he wasn’t making merry, Tommy wrote movie scripts. (He went on to be a successful and prolific TV writer and playwright.) Betty fell in with a fashionable crowd in London that included legendary interior decorator Syrie Maugham, the former wife of author Somerset Maugham. Another famous London decorator, Nancy Lancaster, was an Astor — and a friend. Betty bought boatloads of Syrie Maugham-designed furniture, with which she furnished all her houses throughout her life. Tommy and Betty had a son, Wilton — nicknamed Tony — but the marriage lasted only a few years, and she retreated with Tony to New York.

Betty remarried, this time to stockbroker and grocery store heir Eddie Reeves. They had a daughter, Joan (now living in New York and married to the writer Lewis Lapham), and when Reeves died, Betty tied the knot with mining heir Jock McLean, who, it turns out, had been a witness at her wedding to Reeves. Jock moved her and the two children to Texas, and when that marriage dissolved, she wed oilman Tom Blake Jr., with whom she had two more children, Douglas Blake and Tom Brooke Blake.

In 1960, Betty’s first-born son Tony died in a boating accident on Lake Michigan. Betty dealt with it like she did every tragedy that befell her — with a stiff upper lip. “She had a real strong spiritual side to her,” says Douglas’ wife, Diane Blake, and she believed in the afterlife. If Betty ever got down about anything, it wasn’t for long. “She never looked back,” says Douglas. “It was always about, ‘What’s next?’ She was curious about everything. That’s wha kept her going — her love of life, and will to overlook tremendous pain.”

Betty’s iron will allowed her to ignore the kind of physical pain that would flatten most people. At 88, after returning from trekking in Nepal, she was told she needed to get both knees replaced. When she couldn’t find a doctor who would perform the surgery on both knees at once — the agony would be too intense — she hired two different doctors to do it at the same time in the operating room. Says Douglas, “I asked her afterwards, ‘Mom, aren’t you in a lot of pain?’ And she said, ‘I don’t know what that is.’”

When Betty’s union with Tom Blake failed, she dusted herself off and picked out a new husband: Allen Guiberson, an eccentric oilman who had built the first radial diesel aircraft engine, now preserved in the Smithsonian Institution. His hobby was collecting steam trains, and the big choo-choo he rode around their front yard on Beverly Drive was a neighborhood spectacle. Guiberson even once showed up at a museum ball in overalls and a conductor’s hat — and it wasn’t a costumed affair. Betty’s expanding resume of marriages provided particularly delectable fodder for the gossip pages. In 1973, when she split with Guiberson, New York society columnist Suzy Knickerbocker put it this way: “Betty, ‘Boops’ to her chums, is a strict Christian Scientist. Which just goes to prove you don’t have to drink or smoke to have a good time.”

Wedded bliss escaped her grasp, but Betty was, if not an eternal romantic, a pragmatic. “It’s as easy to fall in love with a rich man as it is a poor man,” she would say. After she divorced Guiberson, she changed her name back to Blake, spending the next 43 years single. When Douglas once asked her why she didn’t remarry, her witty comeback slammed a lid on it: “Oh yes, I’d marry again. As long as he doesn’t drink or smoke, is older than I am, and has more money.”

She was independent, and that more than anything, might have made Betty ultimately shy from marriage. “Betty liked to be in control of things,” remembers Dallas financier Dulany Howland, who met Betty in the late ’40s in Newport. “I got to know her when she’d bring her daughter Joan to birthday parties at our house. Kids would come in chauffeured limousines with nannies and nurses, but Betty drove Joan herself in the car. She always liked to be the driver. She wanted to have her hands on the wheel.”

Tongues wagged when Betty arrived in Dallas in 1943, with new husband Jock McLean, owner of the Globe Aircraft Corporation in Fort Worth. Jock was handsome and steeped in old money; his father was Washington Post founder Edward Beale McLean, and his mother, gorgeous mining heiress Evalyn Walsh McLean, was the last private owner of the 45-carat Hope Diamond, which she wore draped around her neck, stuck in her hair, or dangling from her dog’s collar. The McLeans’ substantial wealth gained them entrée into Dallas society, but not without raised eyebrows: Not only was Betty divorced; she was on husband number three.

Like her mother, Betty was athletic. She swam, played tennis and golf almost every day, and preferred trousers to skirts, a scandalous predilection for the day. When she was spotted shopping in a pair of pants at Neiman Marcus shortly after arriving in town, Jock fielded phone calls from members of Dallas society about the indiscretion. Betty could not have cared less.

“My mother’s favorite expression was, ‘I don’t give a rat’s ass,’ and that’s probably how she responded,” says Douglas. Despite the shaky start, the city eventually embraced Betty’s brash charm, Brahman Main Line accent, and free spirit. She fell in love with Dallas’ Wild West, cando resolve. “There’s a sense that anything is possible here, [and] anyone can be a part of it,” she told W magazine in 1985.

Betty set roots in Dallas, but Newport was always home. Jock bought his new wife a dazzling chateau on Ocean Drive, built in 1937 by English architect William MacKenzie. Seafair, as it was known, earned the nickname Hurricane Hut, since its exposure to the sea made it particularly vulnerable. Ignoring pleas to evacuate, Betty rode out many hurricanes in her Seafair fortress — but, on one occasion, some of her servants drowned trying to leave. During a particularly violent siege, waves ripped away a large sculpture in the front yard, only to wash it back up many years later.

It was at finishing school in Paris that Betty was first exposed to art — Madame Chapon, noticing her charge’s precociousness, escorted her personally to the Louvre three times a week. As she told Newport Art Museum & Art Association director Karl Willers, “I became completely enamored of the 18th- and 19th-century French art, then of course, the thought came to me, ‘Well if these paintings are so staggeringly beautiful, what are they doing today?’” An obsession with modern art was ignited, but she didn’t start collecting until she moved to Dallas a decade later. With Mexico City so easily accessible, she traveled there often, buying works by great contemporary artists Rufino Tamayo, Diego Rivera, José Orozco, and Frida Kahlo. “Mexico City was like Paris before the war,” she told Willers. “Everyone was there.”

In 1951, she opened one of Texas’ first modern-art galleries, the Betty McLean Gallery, and hired artist Donald Vogel to run it. Stanley Marcus told her she was crazy to risk it, but he came to the opening party anyway, along with many of the city’s art elite. The lineup of works on the gallery walls would take your breath away today: Picasso, Monet, Chagall, Dufy, Homer, Pissarro, Renoir, Vuillard, Cassatt. It was an ambitious effort. But Dallas wasn’t ready for modern art and the gallery closed in 1955. “I mean, there was a Picasso for only a few thousand dollars — a seated nude,” Betty told Willers. “People in Dallas back then would rather buy Cadillacs!”

Her sophisticated eye didn’t go unnoticed. Raymond Nasher, who’d seen a $6,000 Brancusi sculpture at Betty McLean’s gallery, was so impressed with her fearless acquisitions that he decided to move to Dallas from Boston and invest in modern art. That bargain-basement Brancusi? It sold decades later for $15 million.

An Art Queen

A year after the gallery closed, Donald Vogel opened Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden, transferring over Betty’s artists and contacts. “Because of Betty’s connections, Valley House started out in an amazing way,” says Donald’s son Kevin Vogel, who now owns the gallery with wife Cheryl Vogel. Despite being wheelchair-bound and hard of hearing during the last few years of her life, Betty spent almost every Saturday she wasn’t in Newport at Valley House, soaking up the art, and asking questions about the artists. “It was like having a wonderful aunt visiting,” says Kevin.

With her own gallery shuttered, Betty looked to New York for inspiration. In the 1960s, she and Lupe Murchison helped open the innovative Park Place Gallery in Manhattan, a forum for experimental ideas that drew avant-garde artists, poets, and composers. A hothouse for emerging talent, the gallery was home to abstract expressionist sculptor Mark di Suvero, whom Betty took under her wing, introducing him to museums and patrons. He became a superstar. She gave pop sculptor Claes Oldenburg his first solo museum exhibition in Dallas, and her Beverly Drive estate was filled with works by New York artists who often stayed at the house, from Oldenburg to Rauschenberg to Richard Lindner.

“The police would circle the block and stop and harass the long-haired artists that would come and go,” remembers Douglas. Many of his school friends weren’t allowed to come over because of the large nude painting by Lindner that hung in the entry. “We definitely stuck out in 1960s Dallas.”

Later, Betty founded the Dallas Museum of Contemporary Arts, which merged with the Dallas Museum of Art, and for 50 years, she sat on the acquisitions committee for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, helping shape its permanent collection. Her sphere of influence was substantial: She was on the board of the Newport Art Museum, served as president of the American Federation of Arts in New York, and was a commissioner to what is now the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Her taste in art proved auspicious. She was an early supporter of Fort Worth artist Vernon Fisher, and in the 1980s, she started buying works by David Bates, while he was still a student at Southern Methodist University. For her own collection, she bought works by Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Jim Dine, George Segal, Jasper Johns, Josef Albers, Joan Miró, and Frank Stella. Most of the art, which remains in her homes in Dallas and Newport, has been bequeathed to her children or to museums.

In late August, about 240 people gathered from across the country for a late afternoon celebration of Betty’s life at Bailey’s Beach, the ultra-exclusive private club in Newport where she had been a member all her life. The American flag was lowered to half-mast, and as the sun set, her son, Tom Blake, took the microphone and told funny, touching stories about his mother. He listed her many achievements, and some of the tragedies she’d overcome. It seemed fitting that her life came to an end in such a beautiful place.

“Three weeks ago she was sitting at Bailey’s drinking a virgin piña colada happy as a clam,” he said. “No matter what problems arose in her life, nothing ever diverted her from being happy, grateful, and loving. She was unstoppable.”

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)