The Jackson Pollock You Don’t Know: Dallas Museum of Art Shows the Other Side of a Master

BY Patricia Mora // 11.16.15Jackson Pollock's "Yellow Islands," 1952

When Jackson Pollock was criticized for “not painting from nature,” he replied, “But I am nature.” In other words, he demanded that outer and inner worlds be merged and, moreover, by hovering over canvases with his famous method of painting, he claimed that he “became more a part of the painting.” Thus, we are presented with two things: a fused version of what constitutes reality and a new iteration of painted works as psychic presence. And it’s all currently on display in a broad array of works at the Dallas Museum of Art in an exhibition titled Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots.

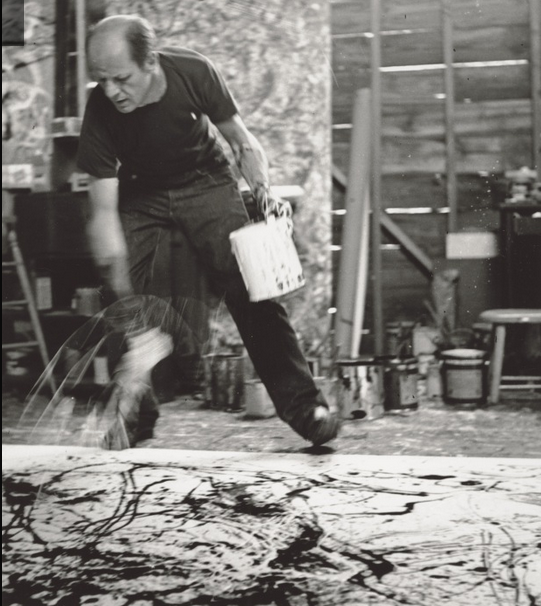

Some reviews of the show focus on the “glamorous” aspect of Pollock as a hard-drinking, wild-driving hunky piece of machismo. After all, that’s ostensibly part of the American mythos that glistens with the likes of James Dean. Well, it might be noted that Dean died in a Porsche Sportster at age 24, while a balding Pollock expired while drunk behind the wheel of an Oldsmobile at the age of 44. He had an additional two decades under his belt, and one of his girlfriends delivers rather dour news: She claimed he and his cronies were “strong but ugly men” who opted to overcompensate for their less than ravishing looks by cultivating a heady aura of bravado.

It takes very little digging in online videos to discover that the whole shebang sounds approximately as pleasant as conversing with Ted Nugent. Thus, how often must we engage in the Romantic notion of knuckle-bustin’ rebels who make fabulous art because they’re engulfed in a perpetual haze of whiskey-induced rage?

Ironically, Pollock made what is widely considered his best art during a sober three-year period that began in 1948. While this isn’t as titillating as the ardent belief in booze as muse, it’s true. And what’s also true is that Pollock helped usher in a storm of new American art that is perhaps still unparalleled. But it also ought to be known that his work was actually propelled by a profound interest in the unconscious (he underwent Jungian analysis for long periods of time), ethnic imagery, Mexican murals and the American West.

While I’m not arguing for art made by choirboys, the latter information is far more interesting than a teenage boy’s fantasy of drunken sprees that de facto invoke creative inspiration. As the aforementioned girlfriend also attests, he would sit at the breakfast table and say, “There are three great artists: Picasso, Matisse and Pollock.” This, however, would soon be followed up with, “I’m no good. I’m a phony.” Such is the price of machismo.

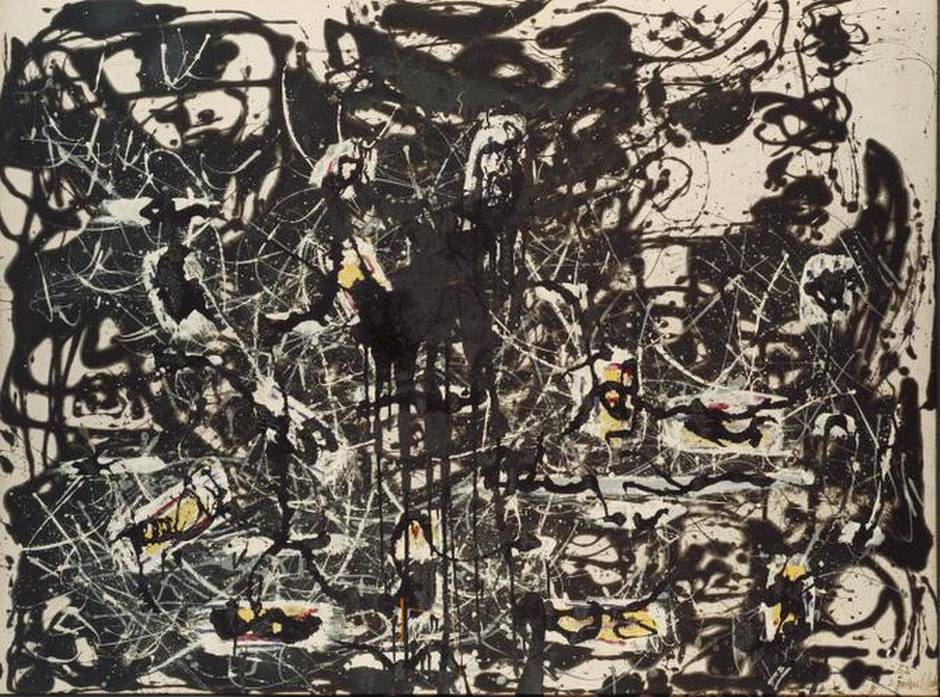

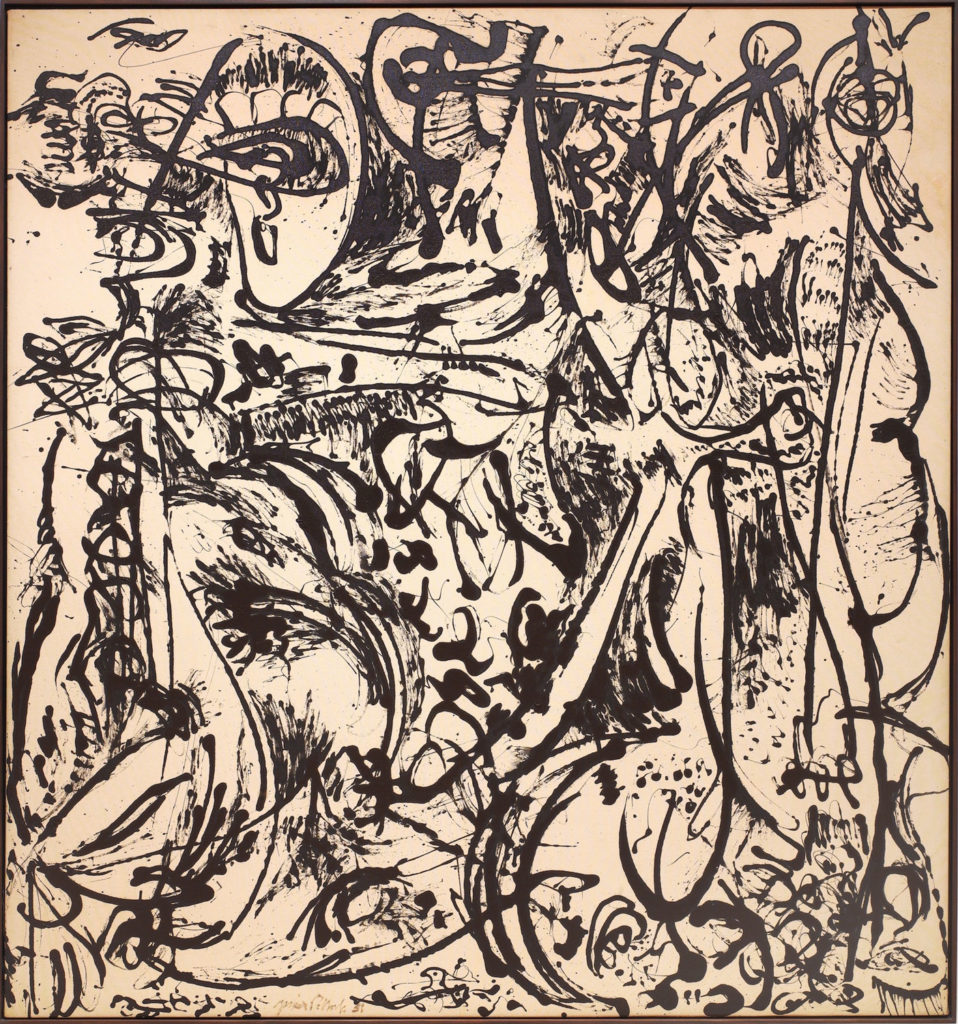

Most importantly, it must be noted that his formidably brilliant body of work eclipses his foibles, habits and self-loathing. When you look at his work, what you see is arresting and endlessly varied. His signature style is instantly recognizable; however, it’s fascinating to see that sometimes the contours of vaguely figurative work glides into a kind of stark and abstract grandeur that is a frenetic and enchanting perpetual motion machine. Moreover, the presence of Leviathans and contorted faces or large eyes emerge; in fact, Pollock’s works operate with the power of Proustian recollection, but his work embodies feelings rather than actual narratives or specific scenes. (Portrait and a Dream, painted in 1953, is an ideal example.)

This, of course, is articulating the obvious. But too often the realms of representational and non-representational art are made out to be stridently disparate. More importantly, both kinds of art share the most important aesthetic moment we have, the instant when an image ignites with sight and we recognize deeply felt moments of passion, anger, joy, melancholy and infinitely more.

It might be noted that Pollock assisted his father limn the contour of the Grand Canyon when he was a boy (his father worked as a surveyor). Meditate on the experience and it becomes clear that it’s about space, descent and scale. Sound familiar? It should. It’s very, very Jungian, and that’s precisely the kind of affecting sensibility Pollock delivered with unnerving speed, elegance and energy. Peggy Guggenheim gave Pollock his start, and for that, we should be grateful. And, as for Gavin Delahunty, curator of Blind Spots, the city owes him a huge debt of gratitude. Like Pollock, he, too, is thinking outside the box — not to mention beyond the frame.

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots, on view November 20, 2015 – March 20, 2016, at the DMA, 1717 N. Harwood Street, 214.922.1200.

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)