Tracey Emin in her studio, London, January 2016 (Portrait Richard Young)

In April, MTV Re:Define will honor British artist Tracey Emin for her groundbreaking work as an art-world phenom and prominent AIDS philanthropist. While together in Miami during Art Basel, Dallas Contemporary deputy director and chief curator Justine Ludwig and Emin sat down to chat about what it means to be an artist, the relationship between creator and creation, and the artist’s dialogue with art history.

The moment when you knew you were an artist.

In 1997, when I had my show at the South London Gallery. Even though I’d shown with Jay [Jopling] in 1993, my show at the South London Gallery was the time when I walked in — first of all, I couldn’t walk in, because there was this really big, long queue that went all the way down the street — and I thought, ‘Oh my god, maybe I’m here early? What’s happened?’

I didn’t understand. People were queueing to get into my show, and then when I got in, there were paparazzi and cameras and thousands of people; it was packed. And I thought, ‘Oh, wow, this is what it’s like to be an artist. I’ve arrived.’ Because, you can be an artist. You can make art. You can have profound thoughts, but if no one sees your art, it doesn’t work, does it?

I remember the first time I saw a reproduction of Everyone I Have Ever Slept With. It had such a profound effect on me because you present such radical intimacy. This seems inherent in your practice.

It’s been like that all my life. I’ve never been some neo-conceptualist. I’ve always made really personal work. Always about first experience.

Do you see a division between you and your work?

It’s totally intertwined. But there is a difference because, in fact, I’ll edit things. I have to edit. I can’t just spew out everything; otherwise, it wouldn’t be art, would it? It wouldn’t be.

There has to be an intellectual pursuit about it. There has to be a dialogue. There has to be a challenge with my mind. Even if it is a cathartic experience with myself, I still have to be aware of that. Otherwise, it would be outsider art, wouldn’t it? And it’s not.

You’ve established a unique language. And text plays an important role in your work. How did you develop this mode of poetry?

I write at least a couple thousand words a week. Every week. I have always written and when I was younger, I had a diary. I love writing. I didn’t start reading until I was 17, and then I read a book a week until I was about 26. That’s a lot of reading for someone who doesn’t read, really. And the same with the writing.

So, once I understood that I didn’t have to play by other people’s rules — if you can read slowly, then that’s fine, and if you write fast, and you can’t spell and you have no sense of English grammar, that’s fine too.

The first book you picked up?

I was ill, and my mom gave it to me. It was a book on Greta Garbo. After that I read David Nivens’ The Moon’s a Balloon. I went for the whole of Hollywood — even Cecil B. DeMille. I got onto directors and everything, then I made a quick leap to Dostoevsky and to Kafka and whatever …

That’s a big shift.

Yeah, well, I didn’t know books like that existed.

It completely changes the way you look at the world.

Totally, and especially when you’re 17 or 18, it’s like, ‘Wow!’ It’s just like a giant sort of way of seeing and getting inside of someone else’s mind and understanding how someone else thinks. So, you take a leap out of yourself. It’s essential.

And when you’re 17 or 18, you’ve never even heard of the word “existential,” yet you’re living it, and suddenly you’re reading Dostoevsky and you’re going, ‘Oh my god! Oh! I understand this.’ When previously you’re considered as not being very bright or, you know, maybe intellectually challenged or with learning difficulties, and suddenly you realize it’s because you weren’t learning the right things or the things you responded to.

That’s a validating realization to have. It’s a good impetus for the work.

Yeah, and when I’ve gotten too good at things, I stop doing them, because I’m not a graphic designer. Once I’ve worked out what the code is, I then have to move on to the next code. A scientist wouldn’t keep inventing the same thing, would they?

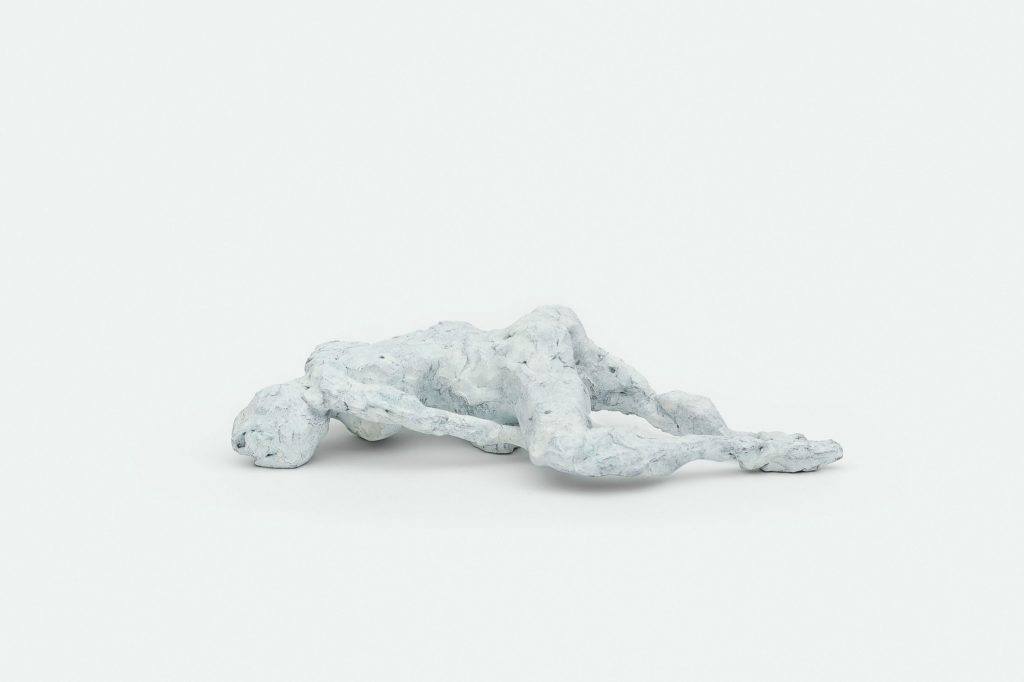

Now, you’re creating massive sculptures. I saw your works in the South of France, and I was utterly taken by them. What brought you to that body of work?

I think probably a bad thing: searing ambition. There’s one big difference in male and female artists. It’s that female artists work on a much easier scale. When you look at someone like Louise Bourgeois, who makes these very delicate, small prints that are very personal, and then she’d make these big, giant sculptures…

No matter how amazing her prints were, and her diaries and her drawings and her sewn works, if she hadn’t made those big sculptures, she wouldn’t be in history as she’s going to be. And I think because I’ve worked with Louise — I did a collaboration with her, and I knew her — it was a good influence on me to think bigger, to think bigger picture. Literally make up-scaled things.

And my mom died last year, and I had a sabbatical as well, and within that sabbatical I had a list of things that I wanted to do. This was like a year and a half ago. One of those things was that I wanted to make a very large bronze. And I did.

Are you continuing with them?

Definitely. But the first ones, they were a fluke. They just worked. It’s amazing, and it’s not easy, because, you can make a small mess, but you can’t make a big one.

The other thing, as well — you can’t get rid of a ton of bronze or two tons of bronze. You can’t. Melt it all down? What are you gonna do? So, you have to get it right. Otherwise, you really have to live with it. You have to store it, live with it, look at it, and think about it.

Often with me, there’s this external and internal thing. It was an internal ambition to be able to take a bigger leap. And I did it.

These works are really contending with history.

Yeah. Too right. They are.

You’re also creating paintings. The minute you’re dealing with oil painting or creating large-scale painting, you’re also contending with history.

See, before, even though that was the art that I responded to — Edvard Munch was my favorite artist — in the end of the ’80s, I realized that was pointless, me going down that route, because when you’re younger, you think it’s all been said or you think that, as a woman, you can’t take on the history of painting because it’s such a male language.

So many people thought that, they stopped painting — not just women. I can paint. So, I think that if you’re good at something, then you should do it. I think one of the reasons I stopped painting … Well, it’s a long story. But, I had an abortion, and when I was pregnant, I couldn’t stand the smell of the oil paint, and then afterwards, I was too guilty to paint. And I felt that I had to, I don’t know, do other things to find myself, reconcile my guilt, work in other ways, which I did for a long time.

And then, weirdly enough, around the age when I couldn’t have children anymore because I’m too old: Wow, I start painting again. Ferociously. And I’m sure it’s got something to do with being tied up with my personal history, the way I work, the way my body works, my body memory and all that kind of thing. I know it is.

Since you’re talking about the artists that you’ve admired and legacy — what would you like your artistic legacy to be?

When I come to Dallas, it’s going to be for MTV Re:Define, and as everyone knows, I do quite a lot of AIDS charity, whether its Terrence Higgins Trust, amfAR, Elton John AIDS Foundation. I’m there, and I’m very proactive in AIDS awareness, challenging people on the stigma of it, et cetera. Right from the beginning.

Being an artist, being in a position to be a spokesperson for these kinds of causes, that’s pretty good. Because if I wasn’t a good artist, I wouldn’t be in a position to do it. It feeds itself. So, something which helps loads of people, you know, for a long time ahead.

My art can help people: Even if people don’t care about my art — they may hate my art, they hate me — my art can help people, and that’s a good thing to know. So, it helps me go to sleep at night, knowing that I’m doing the right thing.

_md.jpeg)