The Anti-Townhouse — Houston Architect and His Husband’s Near Northside House Shows What Can be Done

Proving That McMansions Aren't the Only Way

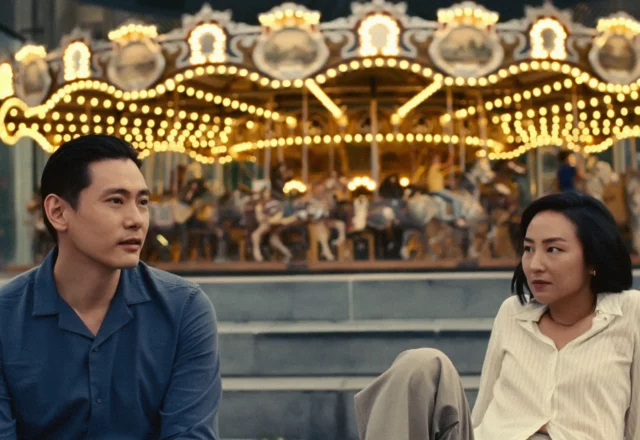

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 09.01.19Ben Koush knows his Near Northside Home is special. (Photo by Pär Bengtsson)

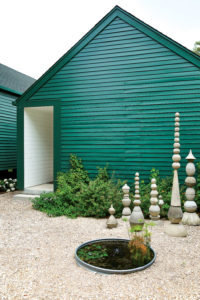

Architect Ben Koush’s shotgun house nestles inconspicuously into its Near Northside neighborhood. It’s a tale of less equals so much more.

Just like the art patrons he admires, architect Ben Koush took a cue from the de Menils for the home he designed and shares with husband, Luis de las Cuevas. The couple’s domestic space, which nods to the vernacular, is sited in a modest, gentrifying neighborhood on the Near Northside — a place where family homes, typically of the bungalow type, pass down through generations.

For an architect, designing one’s own home is both a blessing and a curse. It’s also the calling card of one’s practice.

When clients meet in Koush’s office, it’s at the front of the property, in a simple frame structure connected by a dogtrot porch to the adjoining house — a nuanced preamble. After discussing a future commission, perspective clients are frequently invited into the home that bookends the property, privately screened from the street by the gentle footprint of the architect’s office and an open-air garage.

Bungalow Meets Shotgun House

“We didn’t want to tear anything down. We were looking for an empty lot,” says de las Cuevas, a risk analyst in the oil-and-gas industry whose evenings and weekends are dedicated to his passion, painting. (The home’s second bedroom, transformed into a studio, testifies to the energy executive’s commitment to the practice of portraiture.)

Both Koush and de las Cuevas had peripatetic early lives, so the concept of home is important. Particularly this home — the first they’ve each contributed to as a couple — which is contemporary yet rooted in a historic Houston community.

Koush was born in New York City, attended high school in St. Louis, lived in Atlanta and Portland, went to Columbia for college, then moved to Houston, where his dad was an executive for the May company. Not a fan of Manhattan, he attended Rice University for architecture school.

De la Cuevas’ journey began in Havana; he and his nuclear family left there, not even telling grandparents for fear anything could go wrong. At age 12, he arrived in Houston, where he attended Lamar High School, then Rice.

The couple met in 2014, dated for almost four years, and have been married for two. Their previous house, a historic property in the East End, “Always felt like Ben’s old house,” says de las Cuevas.

“This is very much our nest. It’s the start of our lives together.”

Both have an intuitive respect for their new residence’s working-class, mostly Hispanic neighborhood. Two years ago, they found the ideal piece of vacant dirt, an empty asphalt lot, tucked down a side street, off the main thoroughfare of North Main Street, an area first platted in 1912 by Herman Eberhardt Detering, whose sons would later go on to start the Detering Company in 1926.

Where broken-down cars once resided, a crisp little building fronts the street — Koush’s architectural storefront — while to the left, the carport, clad in beveled-pine siding milled in East Texas, mirrors the surrounding domiciles of the quiet street, that’s a mere eight minutes from downtown.

“It’s like you’re in a little country town,” says de la Cuevas. Adds Koush, “It’s a little like a shotgun house, a little like a bungalow.”

Koush is also a preservationist, a voting member of the Houston Archaeological and Historical Commission, and the author of four books (with a fifth in the works) about the city’s school of mid-century architecture, written for the nonprofit Houston Mod.

He speaks of this dwelling’s footprint, which is one of the hallmarks of his practice.

“The house is about 1,500 square feet, and my studio is 500 square feet, so it’s about 2,000 total. The lot is 6,500 square feet, about an eighth of an acre. We like the neighborhood; most of the people have lived here for about 40 years.

“We wanted to keep the houses in line with that. Our three streets have minimum lot-size restrictions, so that means you can’t subdivide the lots — you can’t build six townhouses.”

Koush references his neighbors’ activist stance through property law and working within city government.

“They saw what was happening and banded together,” he says.

A Menilian Moment + Texas Farmhouse

Guests enter the clean, white space, set to one side of the property, to allow an ample garden. The men have done more than a cursory dive into horticulture and landscape architecture, and both can rattle off an impressive list of plants, which now bloom and/or offer verdant cover for the dual garden areas around which the house is built.

These green spaces, which are quickly filling in as the house marks its first anniversary, serve as visual punctuation points and a pair of outdoor rooms, recalling one of Koush’s inspirations for the home: the courtyards at the Renzo Piano-designed Menil Collection.

In terms of architecture, Koush also cites another influence: former Rice architecture professor Clovis Heimsath, whom he’d met several times after Heimsath decamped to Fayetteville in the 1970s when he became disillusioned with Houston.

Koush resided in a building designed by the elder architect. “This really great condo from the ’60s,” he says. “Right behind Soundwaves. It had two rows of gabled townhouses facing a communal courtyard. I lived there six years; 615 Kipling.”

But it was also a book that shaped this particular house. Koush pulls out a well-worn volume from his office library and says, “I have a copy of Clovis’ Pioneer Texas Buildings, and that was direct inspiration for this house. I flipped through that a lot. It’s local vernacular architecture.

“Clovis used to live right around the corner on Emerson, in the Waldo Mansion in Westmoreland, which he restored in the 1960s. He signed it ‘Keep on truckin.’ He made the drawings.” (Architect Louis Khan wrote the foreword for this influential volume.)

Koush’s success in channeling the building traditions of the Near Northside, adding in elements of outdoor rooms observed at the Menil, and forging a home that’s not out of place, but of place, for himself and de las Cuevas, speaks to the often under-appreciated charms of the city’s built environment.

“Once you scratch the surface, Houston has a real, interesting cultural history that my former teacher at Rice, my mentor Stephen Fox, is very into,” Koush says.

“The architecture and how it relates to people and social classes – rich people and poor people – and how that’s apparent in the physical way the city is laid out. Many times, people think of Houston as being generic, but it’s got a lot of interesting undercurrents. And if you pay attention to them, it can make it seem a more appealing place. You realize how fascinating it is by actually engaging with it.”

That is what Koush has done with his own 1,500 square feet, which feels like a big idea indeed, embedded within a neighborhood of honest, historic and functional domestic beauty.

De las Cuevas seconds these ideas.

“There are all sorts of places where people can build in these neighborhoods and not be totally disruptive, and not have to drive 30 miles or whatever [to work and for amenities],” he says.

“We can live a very comfortable life in this house. We have two gardens. We have that huge deck out there. We have living space. We have a good kitchen with counter space. We have a huge studio for me. How many more rooms do I need?”

The interiors are washed with diffused natural light. They brim with a roster of art and objects. When not on rotating display, they’re installed in a masterful walk-in version of a butler’s pantry called the Gift Shop that speaks to the memorable, treasure-laden liquor cabinet in the Menil House.

In the Koush/de las Cuevas house, the curious and tantalizing contents include wheel-thrown ceramics by Ben’s mom, Pam Koush, paintings by her mother, Elizabeth Herrold, and his own models from architecture school.

In the living/dining space are sculptural furnishings, from 20th-century architectural classics to family heirlooms such as Koush’s high chair fabricated by his paternal grandfather, a talented woodworker, and furniture designed by Koush.

The result is a dwelling as layered as the community around it.

“Now we are basically stakeholders in the neighborhood,” de las Cuevas says.

“You can complain about townhouses and awful McMansions being built everywhere. But if you can, you can try to build something else.”

_md.jpg)

_md.jpg)